Near the top of my list of dumb decisions that nearly got me killed was taking an off-road shortcut from Canyonlands National Park to Moab one spring day during college. Not until we fishtailed and slid to a stop, inches short of a hundred-foot plummet off a snow-covered switchback, did we realize that the four-wheel-drive in our rental truck was not working. After hiking up to the ranger station and getting a tow back up to pavement, we took the highway.

���ϳԹ��� Ethics

Mary Catherine O’Connor and guest writers on environmental issues and the ethics of adventure.Today, I’d rather opt for a bike and skip the SUV altogether. Luckily, a trail network is being built, with the help of 3.4 million from the program, which will link Moab to both Canyonlands and Arches National Parks.

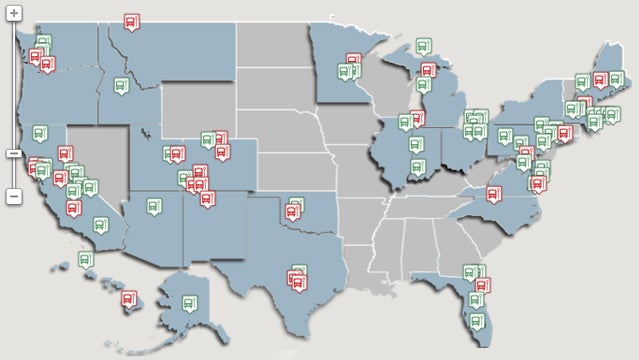

This is one of more than 130 Transit in Parks projects designed to reduce traffic congestion, improve accessibility, and reduce transportation-related wildlife impacts on federal land. Over the past three years, the program has allocated $80 million for everything from non-motorized trails like the one in Utah (called the Colorado Riverway) to alternative-fuel shuttle buses and updated railroads inside National Parks. Lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Reclamation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service were also eligible for funding.

“It’s been a really successful partnership with those agencies in terms of trying to target about $80 million to those projects that will have the most impact to change the dynamic at those facilities,” says Federal Transit Administrator Peter Rogoff.

That dynamic, more specifically, is using the personal vehicle as the default means of traveling to and through federal parklands.

This week, a $1.7 million grant was , Colorado, which will go toward expanding the existing Rocky Mountain Greenway bike and pedestrian trail such that users can bike from Arvada to three different National Wildlife Refuges in the region. Eventually, the trail will extend all the way to Rocky Mountain National Park. In Glacier National Park, $250,000 is being put toward upgrading a free shuttle bus fleet, which travels 50 miles through the park, to improve fuel efficiency.

If these seem like unreasonable government spending projects, you’ve probably never sat in traffic as it inches through a popular National Park like Yosemite or Yellowstone. “People don’t associate traffic jams with our parks, but that’s what we have,” Rogoff says.

And if sitting on a shuttle bus to gaze at mountain vistas sounds like something old people do, consider that a shuttle or a train ride means you can mix up your adventures. Shuttle to a trailhead to start a multi-day backpacking trip that brings you up and over a mountain pass—there’s no car to worry about retrieving. (You might consider a similar approach to reaching trails near your home, as well.)

“It’s not just getting people out of the car, it’s enhancing the experience,” Rogoff insists, and says some transit systems allow users to bring along their bikes. He rebuffs my assertion that getting Americans out of their cars, in any meaningful numbers, is a tall order.

Every time gas prices have risen in recent history, he says, transit ridership increases. When gas prices fall again, so does transit ridership, but—and this is key—it doesn’t fall back to pre-gas-spike levels. Of course, he’s referring to commuters, not park visitors on vacation. Nonetheless, he says two important demographic shifts bode well for transit ridership on federal lands. For one, as baby boomers age, they’ll be less interested in driving and more interested in enjoying the view from a shuttle or train. Secondly, he points to declining numbers of young adults getting their driver’s license at 16 and says this generation is more transit-friendly.

“We’re not naïve, we know there are a lot of Americans who are attached to their cars, and for a lot of National Forests and National Parks, if you’re traveling there from a distance, the car is the only way to get there. But once they get there, providing them a choice is a real opportunity,” Rogoff says.

Unfortunately, it’s an opportunity that exists at the whim of legislators, and funding for Transit in Parks was snuffed in the latest version of the transportation bill (), which President Obama signed last summer. That means once these current projects are complete, there will not be an ongoing funding vehicle for more projects focused specifically on reducing vehicular traffic and providing new transportation options on federal lands (although other funding avenues exist through federal lands programs).

There is the chance that the program will be resurrected—in some form—in future transportation bills. Successful projects such as those seen in Maine’s Acadia National Park will surely serve as case studies by lobbyists who want to see more federal lands transit options. With 2.2 million visitors, Acadia is one of the most popular parks, but congestion was a major issue before the launch of a bus system, on which ridership has grown from 142,000 per year in 1999 to 400,000 in 2012—with an average of 5,000 riders per day.

But the federal government isn’t the only ray of hope. In Yellowstone, municipal transit providers from Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have collaborated on a bus system that not only serves visitors to the national park, but also connects them with nearby towns, including Idaho Falls and Cody.