One million wild animals are killed on American roads . Roads , threaten biodiversity, divide habitats, and interrupt migrations. All those collisions also hurt humans. Every year, wildlife-vehicle collisions (WVCs) kill 200 people, injure 26,000, and cost American drivers $10 billion. And now the Biden administration is doing something about it: a new initiative plans to spend $350 million over the next five years building new wildlife crossings.

“This isn’t just about doing the right thing for wildlife and habitats, it’s also about doing the right thing for passengers and drivers,” secretary of transportation Pete Buttigieg told ���ϳԹ���.

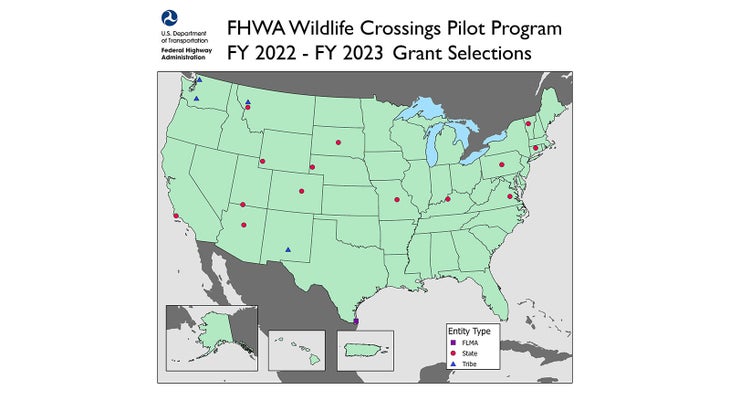

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration is this week announcing the first projects that will be funded as part of its new . Drawing $110 million in grants from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which President Biden signed in 2021, the program “will fund 19 wildlife crossing projects across 17 states and four Indian Tribes,” according to the Department of Transportation.

Projects include a wildlife crossing on Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes land in northwest Montana that aims to provide safe passage for grizzly bears and other wildlife to cross Highway 93 within the Ninepipe National Wildlife Management Area. Grizzlies are protected under the Endangered Species Act and a key grizzly is to reestablish a population in the Bitterroot Mountains. Highway 93 is a barrier to grizzlies in Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness dispersing westwards towards the Bitterroots. The area where the new crossing will be constructed sees , while statewide Montanans average $87 million damages caused by WVCs.

The Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program is part of the secretary’s , which aims to begin the process of working towards a longterm goal of zero road deaths. The strategy is to identify efficacious programs already in existence, then amplify and expand them nationwide. And wildlife crossings are effective. Areas equipped with crossings have seen reductions in WVCs of up to . We just need many more of them.

“If you look at a map, a road seems almost infinitely thin and small,” described Buttigieg. “It looks like a little ribbon across the landscape. In actual practice, especially when you look at the migration or grazing or hunting patterns of a lot of this wildlife, it can have a huge and sometimes even devastating impact on that habitat. And so we know it’s correcting an issue that pitted people against ecology and replaces that with a solution. That’s the right thing to do for the wildlife and the right thing to do for human safety.”

Another project funded during this initial series of grants (an additional $240 million will be awarded over the next two years) will be construction of a very large wildlife overpass on Interstate 25 in Colorado, between Denver and Colorado Springs. Spanning six lanes of highway traffic, the Greenland Wildlife Overpass will provide safe passage for the area’s herds of mule deer and elk as they migrate between the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. That state sees over 3,000 WVCs each year, killing an average of 33 people, and injuring 2,000. When completed, Greenland will be one of the largest wildlife overpasses in the world.

The Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program is funding 80 percent or more of these and 17 other projects, with the rest being drawn from state or local budgets. A grant program, it solicits local expertise to solve local problems, but Buttigieg tells us he hopes that lessons learned can be applied more broadly.

“Think about it in terms of return on investment,” said the secretary. “About $10 billion in damage and harm is done every year from WVCs. That means that investing something like $110 million today—if it moves the needle materially on that damage—it’s going to make a big difference. But of course the best investment is a design that doesn’t create these problems in the first place.”

In addition to mitigating conflicts between road construction and wildlife habitat, Buttigieg says he hopes this program can serve as a model for how major infrastructure projects can better co-exist with wildlife, better serving animals and humans alike.

“As you look at these projects, the 19 that are represented in this round and the future rounds, we think they will also unlock a different way of doing business for the future, demonstrating support for states to use state dollars for better designs in the first place, or to improve or mitigate some of the designs we’ve inherited,” Buttigieg continued. “We just know things that we either didn’t know or didn’t pay enough attention to in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. Let’s put that knowledge to work and do better this time.”

A signature achievement of the Biden administration, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is spending $1.2 trillion rebuilding and modernizing our nation’s aging infrastructure, adapting it to threats caused by climate change, and building the resources required by the shift to renewable energy. The administration also creating jobs and improving the economy. have been created in construction since Biden took office in 2021, and BIL has attracted over of additional private sector investments in manufacturing and clean energy, so far.

“Every time we see a round of funding like this, it’s not just a chance to deal with some of what we inherited, but to send a signal about what the future ought to look like,” said Buttigieg. “Whether we’re talking about freeway designs that divided neighborhoods in urban areas or highway designs that sliced up habitats in rural, mountain, and desert areas, now that we’re doing the right thing, we’re also making sure we don’t make the same mistakes twice.”