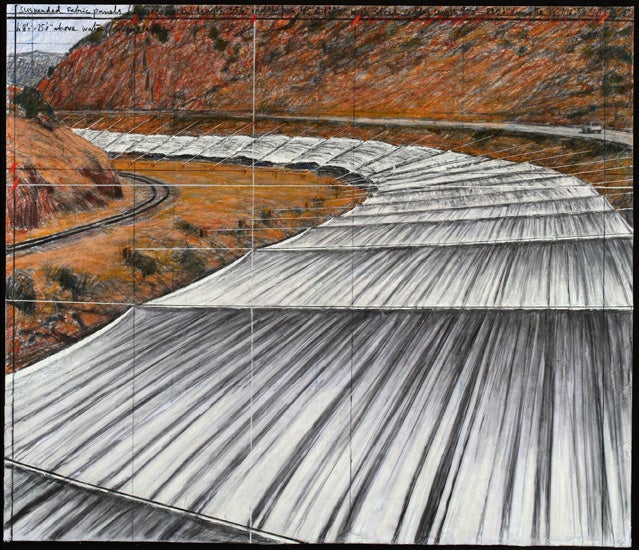

In 1992, during a location-scouting trip, landscape artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude fell in love with the section of the Arkansas River that winds from Cañon City to Salida, Colorado. They imagined a series of large translucent canopies suspended over nearly six miles of a 42-mile stretch of the river. The project, called , would treat visitors on the water or on foot to shimmery views of the sky and surrounding peaks, while drivers on adjacent Highway 50 could view the panels from above.

Over the River

Over the River, Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado

Over the River, Project for Arkansas River, State of ColoradoOver the River

Over the River, Project for the Arkansas River, State of Colorado

Over the River, Project for the Arkansas River, State of ColoradoOver the River

Over the River, Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado

Over the River, Project for Arkansas River, State of Colorado��

Nearly 20 years, numerous local meetings, and $11 million later, the now-widowed Christo is still in love. He’s just waiting on a final decision from the Bureau of Land Management regarding a land-use permit he needs to begin the project. If he gets approval and collects a few other permits, the canopies will be built over a nearly two-and-a-half-year period and would remain up for viewing during two weeks in August of 2014.

Not everyone is enamored with the idea. Many local residents vehemently oppose the project, saying it will distrub the wildlife and create a traffic nightmare. They've formed a protest group named (ROAR).

“You can call it an art project, we don't care one way or another,” says Dan Ainsworth, ROAR’s president. “But it can't be done here.”

It's normal for to cause a stir in the host location. It's part of the process, says Christo. But what's not normal—and is, in fact, unprecedented—is to perform an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in order to get clearance for an art installation on public land. The BLM required the EIS because of the project’s complexity and the potential for impact on public safety and environmental degradation, says Gregory Shoop, district manager of the BLM’s Front Range District Office in Cañon City. Christo expressed eagerness to have the study conducted without prompting from the government. The EIS took two and a half years of work from a great number of engineers, biologists, and other consultants.

As the 1,600-plus-page makes clear, installation of the project would be a Herculean effort. Four drill rigs, with integrated mufflers and vacuums to dampen noise and reduce dust, would be used to help install more than 1,275 steel cables and 9,100 anchors into the riverbanks to support the panels. Special crews hired for safety, security, and biological monitoring would limit stalled traffic on Highway 50 for no more than three minutes per car during construction and prevent construction and dismantling activities from hampering wildlife habits. Christo would also make a $550,000 payment to the to cover administrative costs, environmental impacts on park lands, and income lost from fishing and boating through highway congestion and river-access restriction during construction.

Christo’s team estimates the attraction would float more than $111 million into the local economy. They said it will add $3.4 million to the already vibrant rafting industry, create 620 temporary regional jobs, and bring more than 415,000 tourists to the area.

Ainsworth says that’s a pittance compared with the nearly $800 million spent in Colorado each year by hunters and anglers. He says fellow locals are wrong to think the project would be a windfall and that the negatives will far outweigh the positives. “This will impact people's lives and livelihood,” he says. “There will be people put out of business.”

Here's a quick rundown of ROAR’s grievances: traffic along two-lane Highway 50, no matter what the EIS says, would create intolerable delays and hamper emergency vehicles. The resulting construction, tourist throngs, and dismantling would disturb the local wildlife, including bighorn sheep that live in the river valley. And what if high winds were to toss a large fabric panel or the cables? ROAR has criticized Christo for failing to clean up after his last art installment in Colorado, a huge orange panel called Valley Curtain. It went up in the town of Rifle in 1979, but gale-force winds forced the artists to have it dismantled in just 28 hours. Large concrete anchors used in that project are still in place, which ROAR points to as evidence of Christo’s poor environmental legacy.

The final EIS calls for the development of a bighorn sheep adaptive management program, on Christo’s dime, which would be used to fund any changes of course they’d need to make if biologists monitoring installation of the cables find that the work is causing the sheep significant stress. He’d also need to develop access to suitable habitat for sheep to use during construction and viewing of the project. The wires would be marked to decrease avian impact. And traffic issues would be managed, says the EIS, by designing installations so that no more than 15 minutes of wait time would result, and the existing boat put-ins and recreation access won’t be hampered. As for the equipment left in Rifle, Colorado, the property owners say that they declined the artists’ offer to remove them, preferring to leave them there as a reminder of the project.

Just how much Over the River could negatively impact the region is an educated guess, since it lacks precedent. Research shows that bighorn sheep are sensitive to human encroachment, but given the traffic on Highway 50 and the constant stream of boaters on the river each year, as well as other recreation and hunting in the area, it's not exactly wilderness to begin with.

Ross Vincent, the chair of the Sangre de Christo Group in the , refuses to take a stance on the project because he sees no clear environmental benefits or damages from the project. “I can readily understand [ROAR's stance],” says Vincent. “If I lived next to Highway 50, I'd be pretty upset about it. But at the same time, that's not the same as saying the project is committing considerable environmental harm.”

Still, not all locals share ROAR's point of view. Bob Parker, a local sculptor and emergency responder, was neutral on Over the River until recently, when Christo arranged for a long chain of rusting, empty rail cars to be removed from the railroad tracks on the riverbank opposite the highway. The effort is in Christo's interest, since his crew would need to access the tracks to secure anchors there, but removing the eyesore, which locals lacked the funds and influence to do themselves, pushed Parker to support the project.

And even though river guide Adam Caimi worries about what highway delays could mean for the twice-daily rafting trips he shuttles along the river each summer, he's behind the project because Christo's team has offered to help Friends of the Arkansas River, a clean-up group he started, to pull out some of the rebar and construction debris left by road projects that line the riverbed, creating drowning hazards for boaters and swimmers.

The BLM permit is the project’s biggest hurdle, and it is pretty likely to fall in Christo’s favor. The BLM pointed to the full plan—rather than smaller-scale versions, which the EIS required him to offer—as its favored version. It won’t hurt that Colorado governor John Hickenlooper and Colorado state senator Kevin Grantham have thrown their enthusiastic support behind the project. On top of that, Christo is nothing if not persistent—especially about ideas he developed with his late wife.

What remains to be seen is the degree to which ROAR will turn its voice into action. “Christo thinks everyone here would go look at his panels. I’m not gonna go look at them. But [if the project gets approved] I might lay down on the highway, in front of the drilling rigs,” says Ainsworth.