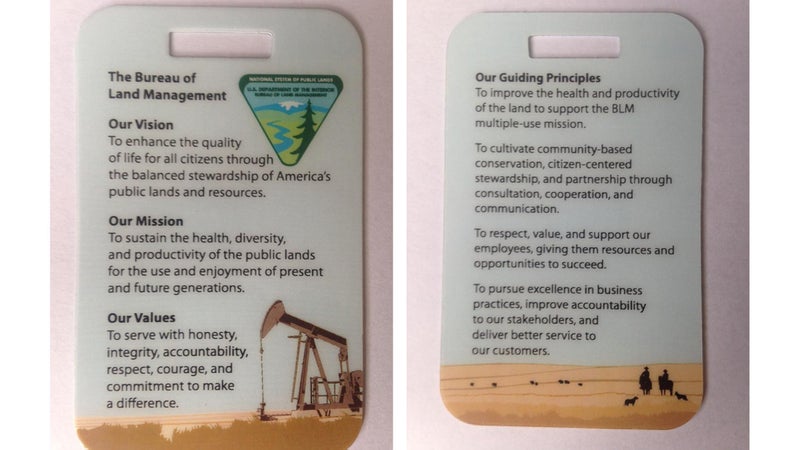

The Bureau of Land Management raised eyebrows this week with a new “vision card”—an ID-sized badge meant to be worn by employees that states is the department’s mission and goals. And by the looks of the card, the BLM is primarily in the business of exploiting, rather than protecting, natural resources.

On the front of the card, just below the BLM insignia, is an image of an oil derrick. The badges were commissioned at the beginning of the Trump administration by then-acting director Mike Nedd, �� The Washington Post.

Since Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke took his post, the BLM has consistently phased out imagery and language that highlighted conservation and recreation in favor of resource extraction and agriculture. It began in April 2017, when a banner image of mountains on the BLM’s homepage was quietly replaced with . It continued in the hallways of BLM’s Washington D.C. headquarters, the , where posters of national monuments were removed. Neither move is particularly surprising, given the Trump administration’s emphasis on energy extraction from public lands.

On one side of the card, the BLM says its mission is to “sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.” On the other side, it lists its guiding principles, in part, as pursuing “excellence in business practices” and to improve “accountability to our stakeholders, and deliver better service to our customers.”

It’s not clear what they mean by customers, but recent history suggests it may mean extractive industries. Last year, the Trump administration ignored conservation groups, recreational users, and local tribes when it decided to shrink Bears Ears National Monument, largely at the urging of oil and mining interests. Last month, the DOI removed Obama-era regulation that restricted methane emissions from federal land-based oil and gas development (a��judge has since ordered an injunction, meaning the regulations must be enforced pending litigation).��And earlier this month, Zinke said the Department of the Interior and the energy industry “.”

All of this is underscored by the to fund much of the Park Service by ramping up extraction on public lands, and auction leases to energy companies for cut-rate prices.

Of course, the 250 million acres of land maintained by the BLM represent different things to different groups. For a Utah rancher, it might be her livelihood. For conservationists, archeologists, and many scientists, it’s a priceless resource. For recreationists, BLM land offers the least-regulated wild space in the country, space where Americans can shoot, build fires, camp, climb, hike, and hunt with less extensive permitting and supervision. For an energy company, it’s profit—a vision the Trump-era BLM seems to share.