My Son, the Manatee

Is it ever too late to become the caring parent you thought you could be? To find out, one man went in search of his adopted manatee—only to discover the many injustices that humankind has heaped upon these hapless marine mammals. And when Junior is fat, slow, and endangered, family values are nothing more than an easy way to break your heart.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

It was a hot and grimy Florida morning, and I was sitting on a derelict pier outside Melbourne, baby-sitting a dead manatee. The manatee, an immature male, had just been towed a mile through the water behind a marine patrol boat after washing up in some snowbird's backyard, and skin was sliding off the poor thing like a blanched tomato. Two teenage boys, sucking on cigarettes, walked up and asked for permission to swim, having seen me get out of the patrol boat. “Sure, why not,” I said, shrugging. The Intracoastal Waterway looked about as refreshing as a sewage ditch, but I wasn't in a helpful kind of mood. I glanced down at the partially submerged manatee, tied by its tail to the dock, rotting in the winter sun. The patrol officer had complained bitterly about having to waste his time on recovery missions, so upon my suggestion, he had left the manatee and me alone to wait for a state marine biologist. How could he stop people from speeding in no-wake manatee zones, he'd grumbled, if he spent three hours out of an eight-hour day on a dead manatee?

A sign declaring “Have Dead Manatee, Will Talk” must have been hanging over the dock. As the teenagers tentatively waded into the brown muck, a skinny, worn-out alcoholic teetered over from his broken-down pickup. “I've never seen one of these before,” he declared, his Adam's apple bobbing like a freaked-out aquarium fish. His breath drowned me in sweet, fermented fumes. “I've always wanted to. I love wildlife.” He peered down, nearly losing his balance. “Not doing so well, huh?”

“Yeah, this cold water, even though it's only in the mid-60s, is pretty rough,” I offered, passing on information I had only just learned myself. “It kills them, even.”

“This one's not dead, though. Just hurting a bit, huh?” Oily fluid was oozing from the body and the odor of decay lingered in the air. After I broke the news, the man ambled away, shaking his head. “Oh, I wanted to see a live one. Never seen one of them.”

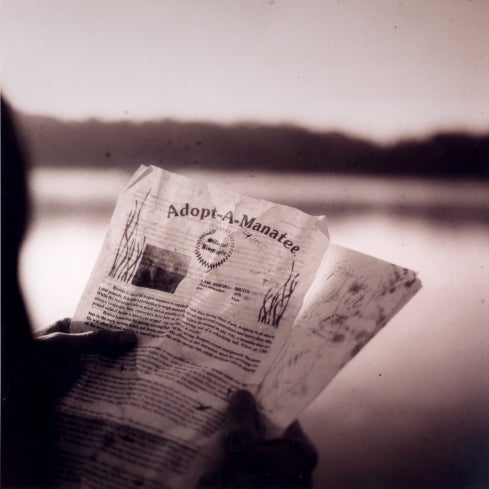

That's what I went down to Florida to do, too—to see a very special live one named Brutus. You see, Brutus is my son. My youngest sister adopted him for me on my birthday last summer, coughing up $20 to the , a Maitland, Floridabased conservation group dedicated to protecting this endangered species. The West Indian manatee, that less-than-streamlined marine mammal, was placed on the endangered-species list in 1973, threatened with wholesale habitat destruction. Up until the 1950s, the giant herbivores were plentiful enough to be hunted, but no one really has a clue how many there were at their peak—guesses range throughout the tens of thousands, and wandering manatees are almost impossible to count. But by 1973 there were likely fewer than a thousand left in this country, and scientists estimate the current Florida population at a mere 2,600, along with small pockets in the Caribbean and Central America. Their death rate rises each year.

The day Brutus's adoption packet arrived, I merely glanced through it desultorily. I read that manatees mate only every two to five years and their gestation period is 13 months. Plus they have a high infant-mortality rate. Didn't sound good. I read more. Manatees live in the shallows of both fresh and saltwater, where pollution and development destroy their habitats. Boats hit them all the time. Well, that's awful, I muttered, and began wondering how best to remove chewing gum from my two-year-old's hair. But then something about Brutus's sad face and sunken eyes caught my attention.

As I read on, I noticed that Brutus, probably in his thirties, was very close to me in age, but we had even more in common. He likes water; I like water. He eats nearly 200 pounds of hyacinths and various water plants a day; I've been known to eat 100 pounds of junk food. He weighs nearly 2,000 pounds; I weigh 170. He is quite the ladies' man, always chasing the girls. I… But what was this? The literature said that Brutus is “often found sleeping by himself.” Was he sad? Bitter? Having a midlife crisis? (Manatees live up to 60 years.) We had to make sure he was OK. “Brutus, we're coming down to see you!” I cried, speaking also for my wife and three daughters. “We'll swim together. Take pictures. Make you feel like part of the family.”

Before heading down to Florida, I figured I should talk to Jimmy Buffet. I'd noticed he cofounded the Save the Manatee Club in 1981 with then-Governor Bob Graham, and I hoped he'd have a word or two to pass on to Brutus. But his publicist's response struck me like a whirring propeller: “Jimmy is not available to participate,” she said. “He is only making himself available for national television programs.” Undeterred, I had her submit some questions for Jimmy anyway. “Do you have any message you might want to give Brutus or any of the other manatees you're helping to save?” I asked, and “Do you know anyone who might have been a manatee in a former life?” The publicist got back to me a few days later and said Jimmy wasn't answering the questions, not even the one about how he might begin a song about manatees. Hell, even I could do that:

Nibblin' on eel grass,

Watchin' some mare's ass,

All of those big boats loaded with Bud.

Swimmin' to warm springs,

listenin' to props zing,

See our backs—

They're covered with blood.

Wasted away again in Manateeville,

Searchin' for our lost celebrity friend.

Some people claim that he'll bring us to fame,

But we know, this is surely our end.

Well, let's hope not, but prospects do look dire for the manatee, despite the efforts of the Save the Manatee Club and a cobweb of federal and state wildlife agencies. Between the club's adoption program, the state of Florida's Save the Manatee license plates, and other fund-raising efforts, millions of dollars are spent each year on rescue efforts, research projects, and educational programs (for humans, not manatees) from Florida to the Carolinas. But it's an uphill battle, waged against such well-connected foes as Wade Hopping, lobbyist for the National Marine Manufacturers Association, who last year called for the species' delisting because the manatees, he said, had made such a great comeback. Hopping speaks for boaters who don't like the no-wake—and even no-boat—zones posted in high-density manatee habitats. Meanwhile, the number of manatees killed by watercraft jumped 24 percent in 1999. Total deaths in Florida last year were 268, a quarter of those due to boat collisions. Most manatees die on impact or bleed to death from propeller cuts, but even broken bones can kill them. Their ribs are solid and heavy, not porous like ours, and when one breaks, it's like a hardwood board snapping in two. The resulting internal injuries can prove fatal.

But in a few of these no-boat zones, the manatees are doing quite well: the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge and Brutus's wintering grounds in central Florida's Blue Spring State Park among them. Back in 1970, when motorboats were still allowed at Blue Spring, only 11 manatees retreated to its warm waters, which feed the equally languorous St. Johns River, on Florida's east side. Now more than a hundred gather there each winter, enough for scientists to classify them as one of three distinct Florida populations, the others being the east coast manatees, whose range stretches from Miami up to the Carolinas, and the west coast manatees, who travel from the Keys as far west as Alabama. For the St. Johns group, the main attraction is Blue Spring itself. Fed by groundwater seeping through limestone bedrock, the spring remains a constant 72 degrees: manatee heaven.

It sounded inviting, but I was told that swimming with the manatees was a no-no. “We consider it harassment,” said Nancy Sadusky, spokeswoman for the Save the Manatee Club. Sensing my disappointment, she hastily added, “We do encourage Passive Observation—you can still hang out near the spring and take Brutus's picture.”

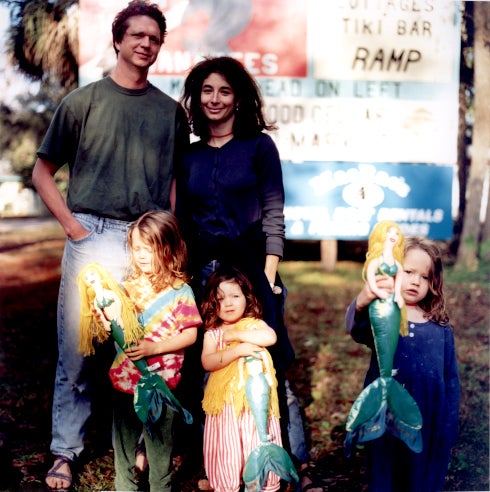

Blue Spring State Park is 30 miles northeast of Orlando, and as we made our way south from our home in Maine, my wife, Lisa, and I tried to prep our kids about Brutus and his friends. Driving down McDonald's-Exxon-Comfort Inn-Jiffy Lube Lane in Orange City, toward the turnoff for the park, Lisa explained that Brutus, like most manatees, could be identified by his unique pattern of propeller scars.

“Why do the boats cut Brutus?” asked Eliza, who's four. Because the boats go too fast in shallow water, we answered.

Then Anabel, her twin, chimed in. “Is Brutus better?” Yes, yes, we said. Helen, our two-and-a-half-year-old, held her own counsel, staring mutely at her manatee book.

“But the boats might cut his back again, huh?” Eliza continued. Luckily we arrived at the spring before we had to answer.

“Bruuuuutus!” the girls yelled, running to the boardwalk that hugged the shore. “Where are you, Brutus?”A lush hammock of live oak and wax myrtle engulfed the bank, making it nearly impossible to see the 50-foot-wide spring. The girls pried their way past dozens of baffled tourists staring blankly down from the boardwalk at the vividly clear water, but all they could see were a few fat catfish and a small school of tilapia. Brutus, along with all the other manatees, was nowhere in sight. The park allows visitors to swim in the upper reaches of the spring run each day—just not near the manatees—and half a dozen people were already splashing around the narrow waterway. Human-manatee interaction wasn't a problem because, understandably, the manatees had left. Park rules state that were one to reappear, everyone would have to hop out of the water. But the manatees usually just leave sooner on their afternoon foraging runs into the 60-degree (or colder) river, traveling perhaps dozens of miles for food and, with any luck, a shallow pocket of warm water. Most get cold stress in water below 68 degrees; they develop internal infections and cankerlike sores, similar to frostbite, on their extremities, which often lead to death. So the park tried to prohibit swimming but bowed to legislative pressure when swimmers and divers complained.

We waited around, hoping against hope that Brutus might show. But hours passed, and finally, dejected, we set up our tent in an RV site at the park. Thirty miles northeast of Orlando might be a great place for manatees, but it's a little less so for humans. The area's sprawling development is inescapable and frightening, and during our entire stay, beeping, churning construction equipment serenaded us wherever we went. Florida has the country's fastest-growing population, and the 2,192-acre park made a poor beachhead in the fight to preserve some semblance of tranquility.

That afternoon, our friends Russell Kaye, Sandi Phipps, and their five-year-old daughter, Lucy, joined us at our campsite. Russell and Sandi had come to photograph the manatees. With all three suffering from strep throat, they were no boost to our sagging morale. Our girls were pouring topsoil over each other when my wife began grousing that the tourists were ugly; Blue Spring gets up to 2,000 visitors a day because of the manatees. “They're a blight on this beautiful natural setting,” Lisa announced.

“What makes us so beautiful?” I asked, still worried about Brutus. A seemingly befuddled box turtle walked by.

“We're not,” Lisa replied. “We're a blight too. We should all commit mass suicide.”

“Not until I see Brutus,” I said.

By the next morning, the manatees had returned. Putting down a mutinous clamor to abandon Blue Spring and head over to the Gulf Coast to the mermaid-and-manatee show at Weeki Wachee Springs, Russell and I accompanied park ranger Wayne Hartley on his daily head count. Our sullen families watched the manatees from the boardwalk as we made the rounds in a pair of canoes. Hartley said that Brutus returns to Blue Spring every year, as my brochure had claimed, but he only stays for a few days at a time and then disappears for weeks. “It's got to be really cold to bring old Brutus in,” he said. At 8:30 a.m. the air temperature was a cool 50 degrees, so maybe Brutus had turned up.

A big man but no manatee contender, Hartley has been monitoring the annual Blue Spring winter retreat for 19 years. One hundred and thirty-one manatees had come up to Blue Spring this season, and he knew nearly all of them by name. We paddled just a few yards past the no-boat zone (PVC piping across the mouth of the spring) and hovered over a bunch of manatees. It was extremely underwhelming. They looked like sunken fat cactuses, as a result of sporadic bristly hairs dotting their bulbous backs. Eventually, one slowly rose to the surface, inches from our boat, revealing its stoppered snout, making me suddenly giddy. It was so close; it might be Brutus. The nose unplugged and a reverberating exhalation, like the spouting of a small whale, echoed across the still waters. Its breath smelled a bit like a deflating tire, only mustier.

“Brutus?” I asked.

“No, that's…Phyllis.”

Another and another and another rose around us. Soon there were dozens of exhaling cactuses surrounding our canoes. I hadn't expected it to be like this, great clumps of them floating beneath us, conserving their energy, as we paddled overhead. One mother had not only her one-year-old calf close to her side, but also a pair of older adoptees vying for nourishment.

[quote]One of the manatees rose slowly to the surface, revealing its stoppered snout, making me suddenly giddy. Its breath smelled like a deflating tire. 'Brutus?' I asked.[/quote]

Hartley began a monologue of greetings that didn't stop until we were back on shore two hours later. “Glad to see you, Floyd. There you are, Jax. No, you're not Jax. Wait, yeah you are, tail buried in sand.” Half of Jax's tail is missing, perhaps from a run-in with fishing line. Next to boating accidents, entanglement is the single biggest cause of injuries.

“There's Georgia,” Hartley continued, taking pictures and recording distinguishing marks while he talked. I half-expected him to give each manatee a friendly slap across the back, he reminded me so much of a local politician courting his constituents. “This is Georgia's third year back. Great success story. Picked up at 63 pounds. Six years at Sea World, released here.” Georgia looked to be at least 1,500 pounds, if not more. “Problem is that Georgia likes people too much. She's even tried to climb steps out of the run to follow someone. She's taught her calf Peaches to like people, too.” He swept his paddle over the water, indicating the whole lot. “The brats, I could beat them all,” he said with affection.

Peaches, by the way, is a boy. You can tell by the proximity of the genitalia opening to the umbilical scar and anus. Males' are closer to the umbilical scar, females' to the anus. Of course, a manatee must roll on its back for you to see this.

One manatee took a shine to me and wouldn't leave my end of the canoe, nuzzling up to me and trying to touch my hand. “Oh, that's Unknown 11,” Hartley said, glancing over his shoulder, noticing a tail scar. Unable to resist, I touched its head. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, this was OK because the manatee approached me, but the state park did not condone such behavior. Unknown 11's skin was rougher than I thought it would be, almost like sandpaper. It came back for more—clearly very fond of me. Hartley said this behavior wasn't unusual. “The more they like hanging around people, the more they hang around boats, and thus the more they get hit,” he cautioned. I asked if Brutus is like this. Hartley laughed. “Naw,” he said. “Brutus is a real manatee. He moves away from the canoe, if he is awake. He's very calm, laid back, though.”

We saw 72 manatees but no Brutus.

That night during dinner at Olive Garden (about the only place in town that serves salad), I got more grief, not only for keeping us in central Florida but seemingly also for the whole manatee situation.

“I wish they didn't give the manatees names,” Sandi said. “What's with calling him Brutus? Or Louie? It anthropomorphizes them. It's kind of weird, don't you think? It makes you want to pet them.”

Ashamed, I didn't mention touching Unknown 11.

Brutus didn't show up the next day, either. The weather had turned warm, with temperatures in the 70s and 80s during the day and only the low 50s at night. Weighing roughly a ton, Brutus, along with most of the other manatees, had little need for Blue Spring. So Russell and I headed over to Melbourne, on the Atlantic Coast, to watch a manatee recovery, which is how I ended up on a dock baby-sitting a dead manatee while Russell went off to meet the state marine biologist. Not surprisingly, our families opted to drive to Weeki Wachee.

About a half-hour after the patrol officer left me and my deceased charge, Russell and Ann Spellman, a redheaded biologist for the state-run Florida Marine Research Institute, pulled up towing her manatee rescue/recovery trailer. We dragged the corpse out of the water and loaded it in back of the trailer. All recovered manatees are given a necropsy to determine age and cause of death, and Spellman decided to do the postmortem right in the parking lot behind her office. The nearest pathology lab was three hours away, and she had to hurry to a meeting where she would be told that her already-meager budget was being cut.

“The first thing I like to do is cut the head off to get it out of the way,” Spellman explained, as scores of flies swarmed around her and the manatee. She was squatting inside the trailer, which had a slick fiberglass coating so it could be easily hosed out. A pervasive stench clung to anything within range. Apparently breathing through her nose as well as her mouth, Spellman sliced through two layers of fat and muscle. Two more quick strokes of her poultry knife (“It has a good long handle,” she said) and the young male's head was severed from its spine. The head slid a few inches on its own fluids and stared out in understandable disgust. “At least he's not a slimer,” she said.

Pointing out puffy, white sores on the animal's flippers, tail, and head, Spellman theorized that it had died of cold stress. Barnacles clung to what was left of the manatee's skin, but there were no signs of recent boat scars.

She sliced through half a foot of flesh and found swollen lymph glands and other signs of infection that supported her initial evaluation. And seeing the manatee cut up, it no longer seemed so surprising that these animals cannot handle what seems like relatively warm water. Although there might be a foot of meat between skin and internal organs, there is shockingly little insulation. The amount of fat this creature had, less than an inch in thickness, would make a seal die of laughter. Russell, for example, has plenty more fat than a manatee.

As Spellman studied the carcass more closely, though, she began noticing odd things—a blood-red liver that should be brown, a collapsed left lung, two ribs out of place. She turned the animal on its side. An ugly white scar that we hadn't seen earlier stretched a foot across its back. “Boat,” she said and then started digging around the ribs. Turned out there were six fractured ribs from the impact. Judging from its size, Spellman guessed the manatee to be a two-year-old that had perhaps still been nursing.

“I love animals, but it's like I'm a fireman,” she said. “You don't see a fireman bawling his eyes out at the scene. You bawl your eyes out watching a stupid schmucky movie.”

Spellman cleaned up the mess, stored the head to be sent off to a bio lab (where its exact age could be determined by growth rings in the ear bones), hauled the carcass to the local landfill, and headed off to her budget meeting. Since it was still extremely hot out and Brutus was nowhere to be found (I had called Hartley to check), Russell and I rushed across-state to catch the Weeki Wachee mermaid show. The girls had already seen the morning performance.

“They've got a summer mermaid camp,” my wife gushed. “Their makeup stays on even when they're underwater. You should see how they hold their breath.”

“Do they look anything like manatees?” I asked, refraining from pointing out that Brutus can hold his breath for up to 16 minutes. The manatees' order is called Sirenia and has long been associated with the mythical mermaids, as Lisa had reminded me earlier.

“No,” she continued, her face flushed, “but to become a mermaid all I'd have to do is be able to hold my breath for two and a half minutes underwater while changing costumes… Did I tell you Elvis was here?”

The show, a musical rendition of The Little Mermaid, was mesmerizing. How did they get that makeup to stay on? One of the mermaids slid right past the underwater window cut into one side of the spring's deep cavern, but I definitely could not see how the mermaid/manatee myth ever started. Christopher Columbus, the first historical source for it, wrote that the mermaids he'd seen were not as handsome as artists had portrayed them. What an idiot! These mermaids looked nothing like manatees. To begin with, manatees' breasts are found under their front flippers and that certainly wasn't the case with the Weeki Wachee mermaids. And there weren't even any manatees around that day. “Those girls are so cute,” the woman behind us said at the finale.

No one could say that about a manatee.

While you could barely even look at a live manatee at Blue Spring, the wild west coast was a different story. That night we stayed in a trailer at the Marine Park Inn on the Homosassa River a few miles up from Weeki Wachee. A huge billboard out on the road said, “Swim with the Manatees.” This we had to see.

We rented a pontoon boat the next morning and slowly waddled up the river toward the mouth of Homosassa Springs—the main attraction for the hundred or so manatees that convene there on cold winter days. Not far from the mouth of the spring, in Homosassa Springs State Wildlife Park (which also features swamp tours and live hippos imported from Africa), nearly 20 tourist-choked pontoon boats and more than a hundred snorkelers were packed in an area half the size of a football field. Manateemania. Not only were these people swimming with about two dozen manatees, but they were also rubbing the manatees' bellies and backs. Some people looked like they were trying to have sex with the poor beasts. Others, like members of a hunting party, were chasing down retreating manatees, desperate not to let them get away.

An elderly couple paddled up next to us in their canoe. It turned out they were Manatee Watch volunteers. When they see unlawful behavior, the couple told us, they approach the swimmers and discourage them from breaking the law. A few minutes after we spoke, this duo broke up a gang of swimmers who had separated a mother from her calf. Mostly, though, they just paddled along, caring but ineffectual. According to the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge, U.S. Fish and Wildlife officers in this area gave out only six tickets for harassing manatees in 1999, and in five minutes we witnessed about 70 infractions. Where were those guys?

We watched as snorkeler after snorkeler harassed the lugubrious manatees. “Hey!” one particularly goofy swimmer yelled out. “He's got my hand with his flipper and won't let go. He really won't!” Take him down, I silently pleaded. Take him down.

[quote]What the hell was going on here? Boats shouldn't be able to motor up to endangered species and drop tourists in their laps. Hell, why not let people shoot them?[/quote]

Lisa, Russell, and Sandi got in to take pictures and a couple of manatees approached them. The manatees performed headstands and even nudged them with their noses to get scratched and petted. Whether this was true affection or simply a result of years of being hand-fed lettuce by misguided tourists was hard to tell.

I jumped in, too. Like everyone else, I just had to get a look from underwater. Although I now knew that swimming with manatees is unhealthy for the species, the animal's giantness is powerfully compelling. “See, we're not all bad,” you're thinking as one gets closer and closer. Then, you reach out and…another manatee is dead.

What the hell is going on here? I began to wonder. This is an endangered species. People shouldn't be touching endangered species. Boats shouldn't be able to motor up to endangered species and drop dozens of tourists in their lap. There shouldn't be signs on the highway exhorting people to swim with the goddamned endangered manatees. Go swim with a Weeki Wachee mermaid! What was the State of Florida doing to these poor, dumb animals? What was the U.S. government doing?

Hell, why not let people feed them, take them home as pets, shoot them even? I've read that the meat tastes pretty good; some people still poach them. Soak their tails in brine and have a party! It really wouldn't matter. They're not going to be around much longer anyway, except in aquariums and zoos.

The manatee I saw underwater seemed to know this. “I'm doomed,” his sad face said, as I kicked to scare him away. I hopped out of the river, revved our engine as loudly as possible, and happily saw a few manatees splash down to deeper, safer water.

We returned to Blue Spring, still hoping to catch a glimpse of Brutus. It was our last day in Florida, and we had a few things we wanted to tell him.

We paddled out past the mouth of the stream and into the St. Johns. It is a wide river, stained brown with tannin, and it was unlikely we would see anything underwater. It was Sunday, and dozens of boats slowly motored up and down the river. Only a few disobeyed the no-wake rule.

Occasionally, one of us would call out, “Brutus!” and a flock of egrets would take to the sky. Once we startled a 12-foot alligator that was snoozing on the bank and the creature scurried directly toward our canoes. (Alligators, by the way, don't eat manatees; the lummoxes are just too big for their jaws.) Finally, when we'd been bitten by enough mosquitoes and the girls were scanning in all directions for attacking alligators, I stood in the canoe. I had been planning to make one last plea. Perhaps I'd started out as a deadbeat dad, but now I truly cared. I wanted to be there for him, the son I'd never known. But something profoundly different came out of my mouth. “Brutus!” I yelled. “Don't come back! We're not worth it!”

Brutus did come back, though. Two weeks later, Wayne Hartley e-mailed that he had returned. Like all manatees, he needs that warm water on occasion. Brutus has been coming to Blue Spring for at least 30 years and he probably will continue to do so until the day he dies.

I hope I never see him.

W. Hodding Carter is the author of Westward Whoa�����Ի� A Viking Voyage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|