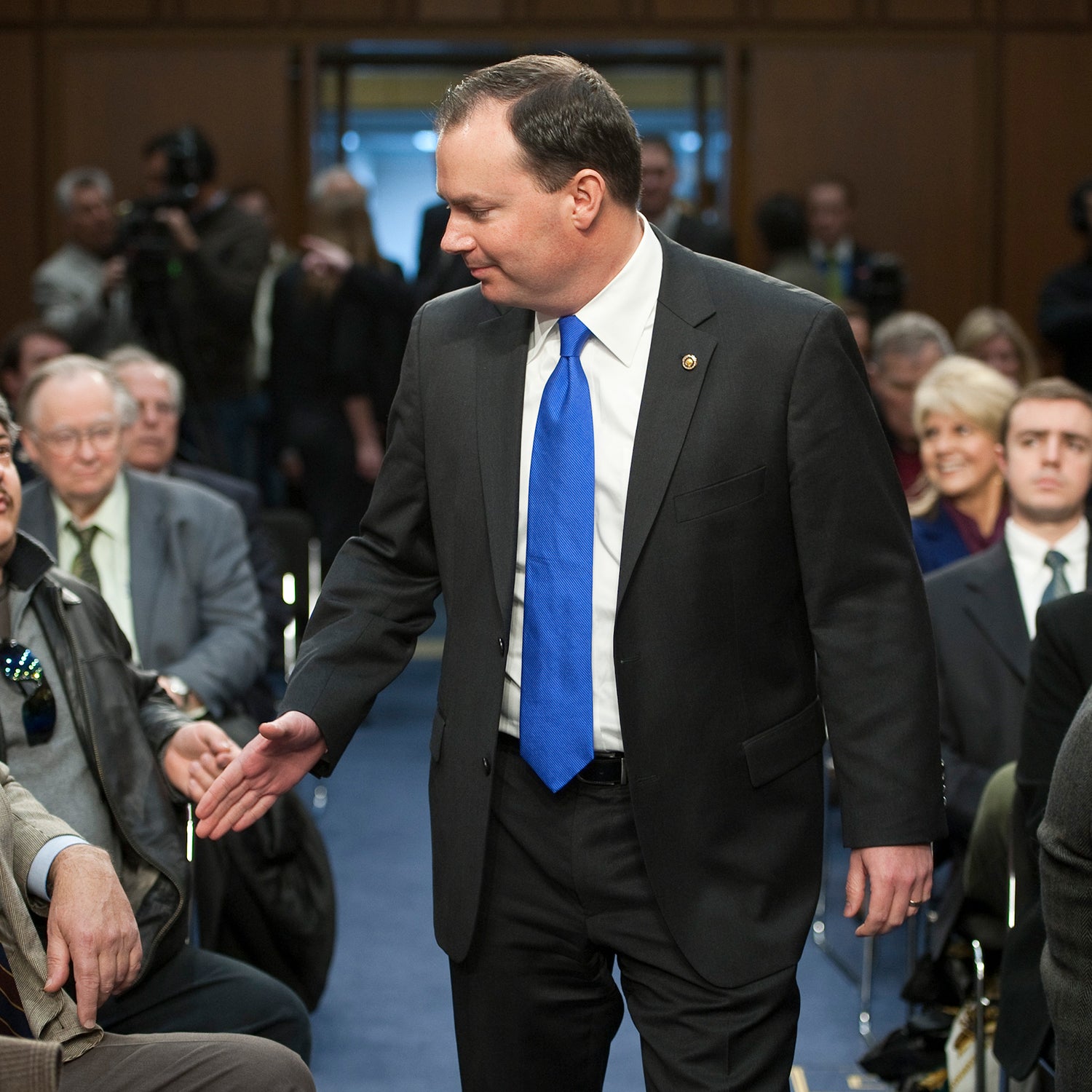

Last Wednesday, Utah Republican Senator Mike Lee introduced a new bill that would limit “the establishment or extension of national monuments in the state of Utah.” Except…it feels a lot like old bills he’s introduced, with no success, in the past.

This go-round, Lee’s calling it the PURE Act, which stands for “Protect Utah’s Rural Economy.”

It’s his latest political spike strip, meant to impair a president from creating new national monuments in his state. In September 2016, that would prohibit extensions of monuments without the go-ahead from Congress. In August 2015, it was a bill that would (which was nearly to a bill he co-sponsored seven months prior). Actually, Lee has tried to squash presidential power to create monuments since at least June 2011 with his , which sought to curb the establishment of new national forests, parks, wildlife refuges, and the like.

But the PURE Act is slightly different—at least in tone, name, and, perhaps most important, in the political era it’s being introduced. Last year, the Trump administration rolled back several national monuments, and two of those—Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears—are in Utah. “In both cases, the local residents were not appreciative of the monument, and the state did not have a voice in the designation itself,” Conn Carroll, communications director for Lee, told ���ϳԹ���. Lee’s PURE Act “would provide pretty much the same protections that Wyoming has,” Carroll says.

It’s maybe a little-known fact, but it’s true that Wyoming and Alaska restrict the establishment of new monuments within their boundaries unless Congress approves. Both were special cases, passed for different reasons, but it’s something Lee seems very interested in bringing to Utah.

For Alaska, this moment came in 1971, when President Richard Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). It was meant to settle disputes over Native lands there, and it gave the secretary of the interior—at the time, Rogers C.B. Morton—the ability to withdraw lands from ANCSA that he thought should be protected and gave him the ability to set aside up to 80 million acres for potential conservation. But there was a catch: Congress had five years to green-light that land for federal protection or else it would be handed back for potential development. By 1978, it still hadn’t made any action on the land.

This is a question of their voice being drowned out by distant federal bureaucrats. That’s the narrative at least.

In December 1978, President Jimmy Carter of Alaskan land as monuments for federal protection. “It’s noted by some folks as the most significant land conservation measure in history,” says Alexandra Klass, a distinguished McKnight University professor at the University of Minnesota Law School. Alaskans, however, were not too happy. Protesters , then organized the Great Denali Trespass, in which upset locals entered the park to shoot off guns in protest. To appease angry state legislatures, Congress passed a law putting an end to presidentially declared monuments.

In Wyoming, drama over public lands and the president’s use of the Antiquities Act there started much earlier, in the 1920s, when—according to one article—rich conservationist John D. Rockefeller started snatching up land near Jackson Hole that he would later donate to the federal government. The understanding was that the land would be set aside for a national park, and by 1943, when that hadn’t happened, Rockefeller threatened to sell. So President Franklin D. Roosevelt stepped in with the Antiquities Act, establishing Jackson Hole National Monument.

People were outraged. Ranchers drove more than 500 head of cattle across the monument in protest, egging the National Park Service to stop them. Soon, Congress passed a bill that no more lands could be set aside as monuments in Wyoming—but Roosevelt vetoed it. More drama ensued. Finally, in 1950, seven years after Jackson Hole was designated, it was folded into Grand Teton National Park. Part of the compromise the federal government made with Wyoming legislators was that no further monuments could be established in their state.

Lee’s PURE Act follows the Wyoming mold, says John Ruple, a professor at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law. “It’s a reaction to the president-declared monuments,” he says. “This is a question of their voice being drowned out by distant federal bureaucrats. That’s the narrative at least.”

At , the federal government controls more land in Utah than in Alaska or Wyoming (61.3 and 48.4, respectively). Utah congress members, like the Trump administration, have made it pretty clear that they see the value of public land in what can be extracted from it. So Ruple says Lee’s attempt to stop monuments in Utah is “making sure that lands don’t get taken off the table for mining and gas.”

Lee’s office disagrees with that take. Carroll, Lee’s communications director, says the bill is about putting Utah decisions in the hands of Utahns. “What has to be stressed is we’re not talking about undoing Zion or undoing the national parks. We’re talking about a bunch of Bureau of Land Management land that is not visited by that many people,” he says. (Nearly 1 million people visited Grand Staircase-Escalante in 2014. By way of comparison, Utah’s famous Arches National Park saw that year.)

Some of Lee’s were oil and gas companies, , and he is also representing anti–public lands Tea Party interests. Lee was given a check for more than $111,000 during his campaign from Kirkham Motorsports—whose owner said during his own that he was in complete support of opening up public lands to the extraction industry.

Lee, too, is a land-transfer advocate. “When it comes to federal parks that already exist, we don’t think those need to be transferred to state control,” Carroll says. “But when it comes to the other millions of acres that haven’t been designated yet, that are not forests or not monuments, we do think that should be transferred to local control.”

And from the Outdoor Industry Association that, compared with the extraction industry, three times as many Utah jobs depend on the outdoor recreation opportunities provided by Utah public lands, Lee writes in a statement on his website, “Rural Americans want what all Americans want: a dignified decent-paying job, a family to love and support, and a healthy community whose future is determined by local residents—not their self-styled betters thousands of miles away.”

“Utah should embrace tourism,” Carroll tells ���ϳԹ���. “But tourism can’t be the only focus.”

If there are plenty of jobs in Utah because of monuments, then maybe it’s the last part of Lee’s statement that tips his hand—that this is about Utahns deciding what’s good for Utah. When I ask Carroll, he says that’s exactly right.

“You can have lots of arguments [if monuments are] good for the state of Utah or bad,” says Klass, the law professor. “It has certainly helped the tourism industry but is less good for extractive industries. So who gets to decide what’s good for the state of Utah?”

Trump has shown he’s willing and even an advocate for public lands rollbacks. But Ruple thinks the president might hedge at signing the PURE Act, because while it does fit into his M.O. for putting profits over conservation, it cuts sharply against his love of his own authority. “I think that’s an interesting question,” Ruple says. “Would a president sign a bill that limits his own power?”