The Men Who Dream of Bigfoot

A handful of primate researchers believe Sasquatch is real, and they take their search for the creature very—very—seriously.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

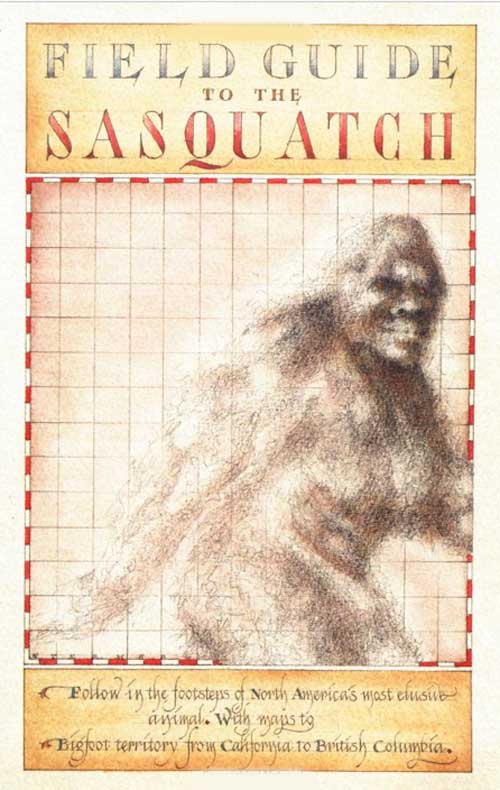

Among those who believe that such a thing as the Sasquatch exists, there is general agreement that the creature probably stands between seven and ten feet tall, weighs between a thousand and two thousand pounds, has elongated arms, is covered with either black or auburn hair (depending on the season), and often walks scores of miles a day on feet that may be as long as twenty-two inches-this last and most prominent physical characteristic having spawned the lay term for the beast, Bigfoot. , a handbook by David George Gordon, a marine biologist, describes the typical Sasquatch as “generally reclusive and shy” and suggests that it is omnivorous, much like a bear. Like many Sasquatch reference books, the field guide also suggests that the Sasquatch may have evolved from the Peking Man or some other prehuman anthropod in an evolutionary path that has led to a point somewhere between the orangutan and the human, and that its most likely habitat is the forests of the Pacific Northwest. (Sasquatch sightings have been reported in every state except Hawaii.) But almost every other detail about the creature-whether it is nocturnal or diurnal, passive or aggressive, lives alone or in groups-is disputed by the people who regularly hunt for the Sasquatch. They also argue over whether a specimen should be killed and studied or whether the Sasquatch should be treated as an endangered species and simply photographed in the wild and left alone.

In the same way that it is impossible to say precisely how many, if any, Sasquatch there are in the millions of acres of forests in the Pacific Northwest, it is also impossible to say exactly how many people are searching for them. There are a few prominent investigators: Peter Byrne, a flamboyant former R.A.F. pilot and African safari guide, who now runs the Bigfoot Research Project on Mount Hood, in Oregon; Cliff Crook, a mild-mannered gardener who is the executive director of suburban Seattle's , the “nonprofit foundation for the preservation of the Sasquatch”; and RenĂ© Dahinden, who works out of a camper that in off weeks he parks on the grounds of a Vancouver, British Columbia gun club. And there is also any number of investigators who work anonymously in the woods on their own. It is thought that most ” believers,'' to use their term, tend to attach themselves to the group that invariably forms around a particular region's best-known figure; these groups then become like little tribes dotting the wilderness of the Cascades and the Coast Range mountains through Northern California all the way into southern Alaska. Investigators are known to have established several twenty-four-hour Bigfoot hotlines, one of which is toll-free, and another which uses a fifteen-page hoax-detection questionnaire. They have identified the golden-mantled ground squirrel as a prime Sasquatch food source, and they have helped establish protection ordinances like the one in Skamania County, Washington, which, should it ever be invoked, will impose a ten thousand dollar fine or up to five years in jail on anyone caught killing or injuring a Sasquatch. Most likely, the ranks of Bigfoot investigators alternatively swell and thin, in the manner of a self-regulating herd, as someone either supposes that he has spotted the beast or any of its telltale signs and, as a result, joins the hunt or loses hope and quits after months, or years, or even decades, without any sign of it at all.

Even the total number of Sasquatch sightings is unknown. This is partly because word of a sighting often goes directly to the local investigator and his allies, who are unlikely to share their information with other groups. And the interest of local newspapers in the ongoing Sasquatch investigation fluctuates over time. The most recent high point began in the early eighties with a wave of reported sightings and culminated in 1987, with the release of —a film that many investigators, even though some of them had consulted on it, felt trivialized the phenomenon. To date, the closest anyone has come to what Bigfoot researchers refer to as “a geo-time pattern'' is in postulating that the number of sightings in a given area increases in direct proportion to the number of campers that happen to be there. At the moment, there is a feeling among some investigators that the quality of reports may be declining, because of an overall lack of training and standards. “The Sasquatch at this point is the side issue,” Ren Dahinden says, in his thick Swiss-German accent. “The driving force is the people and their egos, their personalities. The good ones, they are in it totally, because in this business you can't be in it part-time. You have to be in it totally and above everything. The bad ones, they are the rejects from the U.F.O. field.”

There is plenty of evidence that Bigfoot exists—if you have faith in the evidence. Thousands of footprints have been turning up all over the Northwest since it was first settled, when Indians began describing them in legends. In 1811, David Thompson, the Northwest's first white explorer, described such a footprint in his journals. There are numerous feces samples, which investigators tend to keep in Zip-Lock storage bags, and there are many hair samples. One man in Eastern Washington discovered what he maintains is a Sasquatch nest—a mass of sticks and twigs tangled with reddish-brown hair and doused with a putrid stench, which is said to be the creature's trademark; he keeps it tucked away in his basement. After sifting through hundreds of plaster casts of footprints and talking to scores of eyewitnesses, Grover Krantz, an anthropology professor at Washington State University, in Pullman, has hypothesized a possible Sasquatch skeletal structure and has given it the scientific name Gigantopithecus blakii.

But the best-known and most controversial piece of evidence for the existence of the Sasquatch remains what experts refer to simply as the Patterson film, taken in 1967 by Roger Patterson, a part-time rodeo cowboy from Yakima, Washington, and Robert E. Gimlin, Patterson's friend, in Northern California along Bluff Creek. In a few blurry, over-exposed seconds of color film, a large, hairy female (its “pendulous breasts'' are invariably referred to in studies of the film) lumbers along the creek and into the dark of the woods. The Disney film studio once examined the film ( “If it is a fake, then it is a masterpiece,'' a technician was quoted by a Sasquatch investigator as saying); books have been written about it; and it is shown religiously at Bigfoot-related gatherings or events. Over the past twenty-five years, the Patterson film has become the Zapruder film of Bigfoot hunting-obvious proof of a fur-suited hoax for those who don't believe, and incentive to press on with the search for those who do. The film and its considerable royalties have also been at the center of numerous lawsuits, with as many as seven different people claiming that Patterson sold them sole ownership rights while on his deathbed.

In fact, the dark side of the Bigfoot hunt-the bitter disputes that obsess the investigators as they proceed on their quest-may be its single most tangible aspect. In a recent letter to Ray Crowe, the president and founder of the Portland-based Western Bigfoot Society, Peter Byrne said, “There are a number of rivalries in the Bigfoot field. Their principal basis is of course the belief that at the end of the Bigfoot rainbow there lies a pot of gold. …[h]ad they over the years projected a fraction of the time and money that they spend vilifying each other on Bigfoot research [they] would surely have solved the mystery by now.” And not long ago Professor Krantz told me, “You have to watch out, because there's a lot of backstabbing.”

In many ways, the Western Bigfoot Society is typical of the Northwest's numerous grass-roots Bigfoot organizations. It counts about forty people as members and meets on the last Thursday of every month in the basement of Ray Crowe's store, Ray's Used Books, just outside Portland, Oregon. Ray has decorated the meeting room with a mixture of large footprint casts, oddly twisted willow branches, a 21.6 cm. strand of cinnamon-colored hair, maps of nearby wilderness areas, with pins marking recent Bigfoot sightings, and tabloid headlines that the group finds humorous ( “Beautiful Women Help to Lure Bigfoot,” reads one. “Sasquatch Likes to Study the Ladies.”). Lately, Ray has taken to putting up photos from the group's occasional field trips, like the one to the nearby Primate Research Center, in Beaverton, Oregon, or the one to the Trojan Nuclear Power Plant, in Rainier, Oregon, where Ray thinks the buzz of the power lines may act as a lure.

In the past, speakers at the meetings have included a dog trainer, who addressed Bigfoot's fear of dogs (a phenomenon often mentioned at Ray's meetings); a member of a local search-and-rescue team, who said that the media had neglected to mention that a three-year-old boy whom he rescued in the summer of 1989 from the forests around Mount Hood had credited a “large hairy man” for keeping him company during the long night; and a former paramilitary officer with the National Security Agency, who, on a top-secret mission somewhere in the rainforests of Mato Grosso, Brazil, photographed what he now thinks must have been a Sasquatch, only to have the film confiscated by higher-ups. On one occasion Ray even invited a U.F.O. expert who is a vocal proponent of the theory that Sasquatches have come from another world-a postulate that the W.B.S. as a group opposes. “They may be full of poop,” Ray said, “but I figure I might as well let them have their say.”

Like most part-time Bigfoot investigators, Ray, who is now fifty-five, got into Bigfoot hunting by accident; he was doing research for a novel that included a Sasquatch rape scene and then decided to research the Sasquatch beyond the scope of the book. Shortly afterward, in 1991, he founded the W.B.S., and then began , a monthly newsletter containing Bigfoot gossip, inspirational quotes, and the latest sighting information people have related to Ray. Once in a while, Ray publishes letters, like the one that Erik Beckjord, director of the U.F.O. & Bigfoot Museum, in Malibu, California, sent him, which complimented the W.B.O.'s work, or the letter that Ray himself sent to the United States Forest Service, citing the Freedom of Information Act and demanding to see the Mount Hood National Forest rangers' Bigfoot log book, if it exists. (Ray thinks the rangers may keep a log of Bigfoot sightings.) A few years ago, on a spring evening, Ray had his first Sasquatch “experience,” as he calls it, which began when he accidentally scared an elk away from his camp, at the end of an old logging road. “I was getting ready for dinner and while I'm standing there I hear what sounded like these two giant birds arguing,” he told me. “I say arguing, but they were chattering, really. And, anyway, I just assume that they were two Bigfoot, just arguing with each other-p.o'd at me for losing their elk for dinner.”

RenĂ© Dahinden, who is sometimes called the giant of the Sasquatch field, has a rĂ©sumĂ© that is almost a history of modern Sasquatch investigations. He began in 1956, shortly after he arrived in Canada from his native Switzerland, during what is sometimes called the golden age of Sasquatch hunting. After the Patterson film was taken, he spent several months examining the scene of the shoot. His first full-time Sasquatch work was in 1960, as a member of the fabled Pacific Northwest Expedition, financed by Tom Slick, a Texas oil-airline-and-ranch magnate who also financed the American Yeti Expedition in the Himal-ayas and who died in a plane crash that some Bigfoot investigators believe was mysterious (Slick was said to have been on the verge of the secret of the Yeti). Since then, Dahinden has never stopped investigating-supporting himself financially in part with the interest in the Patterson film that he bought from Patterson's widow, with royalties from his book, , and by working at the Vancouver Gun Club in Richmond, British Columbia. Barbara Wasson, in her book Sasquatch Apparitions: A Critique on the Pacific Northwest Hominid, said of Dahinden: “Ren walks as he lives, securely, energy pervading each step, generating a rich supply of drive and magnetism. He either attracts or repels others, as he sees fit. He seduces admiration from the majority of people, enemy as well as friend, or lashes out to win, where necessary, and to determine realities. Dahinden can cope with a rain soaked floor tarp, though he hates it, in the interior wilds of British Columbia or a formal academic gathering. He does this by being himself at all times, honest, realistically critical, at ease with others, and always challenging. He dresses in dirty torn clothing, shoveling gunshot from peat fields for hours, at home in mud-soaked trousers and sweat; or in clean pressed casual attire, neat and attractive, an eye appeal for females, fresh cologne radiating from a ruddy, scrubbed unwhiskered face.”

Though he has never seen a Sasquatch himself, RenĂ© Dahinden is said to have one of the most extensive Sasquatch files in the world, which includes tape recordings of conversations with thousands of people all over the Northwest who have seen a Bigfoot in the past century or so. It is also said to include information regarding all those people and regarding other investigators who talked to the people who say they saw a Bigfoot. “If a guy is in the newspaper, let's say, with a sighting or something like this, then we look at him,” Dahinden says, pronouncing his 'w's as 'v's “We know all about him. We tape conversations. We listen. We have rooms full of files. Probably ninety-nine per cent of the people we are dealing with, we have them on file. We cover the whole of North America. The F.B.I., the C.I.A.-they have nothing on us.” Dahinden prides himself on the files concerning two rival investigators, Peter Byrne and Grover Krantz. Regarding Krantz's most recent book, , Dahinden told me, “Not to be nasty, but it's the worst book ever written.”

One evening, at a Bigfoot festival in the foothills of Mount St. Helens in Washington, Dahinden talked mostly about investigators; he was particularly upset about the way one recent sighting had been handled. “What was it, last year?” he asked. “We had three kids, I think. Saw one of the things out on a lake. And here's the investigator asking how big was his eyes! You don't ask how big was the eyes. He was across the lake, for Christ's sakes! What kind of a silly question is that?” The next morning he gave me a tour of the converted Ford van he uses as a base for field research. It has a tired green cabin on the back of it and is equipped with a wood-burning stove, an inlaid map table that came from an old McDonald's, and a gun rack that holds a rifle, two cameras with telephoto lenses and automatic advance mechanisms, a video camera, and a simple point-and-shoot camera.

After the tour, Dahinden sat on his bunk, lit his pipe, and talked to me about his thirty-seven years in the field. He wore old khakis, a frayed work shirt, and camp sneakers, and the autobiography of Lee Iacocca lay half read on his pillow; he looked like a tired field marshall, and he spoke as if he were more concerned with the aftereffects of a significant Sasquatch discovery than about actually finding one. “I'm afraid what will happen if the Sasquatch is found by me or somebody else is that the people with the so-called brains and logic, the scientific community, will—knowing what I know about human nature—the government will go to the scientists who rejected this totally with us, the ones who know nothing about the Sasquatch, and they would reinvent the goddamned wheel,” he said. “Guys like me who have collected ten thousand bits and pieces of information would be shoved aside. In Canada, they would spend six million just to decide what to do. But I already know what to do.” He banged on his bunk. “Of course I want to be the guy who finds the Sasquatch! Oh yeah-glory, fame, everything I can wring out of it. But, more than that, I'd like to take the scientific community and beat the shit out of it. Of course, the older I get, the more I realize that's just a pipe dream.”

When we finished talking, Dahinden marched out of the cabin and across the campground, his chin in the air and his notes shoved under his arm like a riding crop. A crowd was assembling near a makeshift stage. Footprint casts were scattered across a long table, and the people shared blurry photos and details of recent sightings. At the center of the exhibit, centered on a table draped with white paper, the Patterson film played over and over on a small video screen. Soon, Dahinden approached Datus Perry, an old man with long white hair and a long white beard who works in kitchen-waste recycling and, possibly because of this (he often smells of lard), claims to have a knack for Sasquatch sightings. (At that time, Perry had logged approximately a dozen sightings, mostly while burying explosives in lava caves with his wife.) Perry's let-them-come-to-you approach is completely opposed to Dahinden's head-on investigative style. To make things worse, Perry had set up several life-sized cardboard Bigfoot cutouts, which are much too pointy-headed for most investigator's tastes. “You're a disgrace!” Dahinden said to Perry.

“You ain't never seen one!” Perry snarled back. “And you never will if you keep on smoking that pipe!”

In the halls of academia, Bigfoot-related research is often discriminated against and lumped in a huge category that includes research on aliens and the Bermuda Triangle. The publications that give it the most coverage tend to be sold in supermarket checkout lines; as a rule, Sasquatch research grants are hard to come by. Grover Krantz knows this firsthand. For a long time, there was a professor on the academic review board of Washington State University who was a nonbeliever, and until that professor retired, in the late seventies, Krantz was consistently denied tenure in the department of anthropology. Krantz ran into similar public-relations trouble a few years later, when the public at large heard about his controversial proposal to kill a Sasquatch specimen (“[B]e absolutely certain the quarry is not a human being,” he warned in one paper). The school switchboard was flooded with calls suggesting that Krantz be taken as a specimen too.

Usually, however, as the author of some of the first scholarly anthropological studies to deal with Sasquatch skeletal structure—Anatomy of the Sasquatch Foot, Additional Notes on the Sasquatch Foot, and Sasquatch Handprints—Krantz has received the critical attention he deserves: He was a keynote speaker at the last international Sasquatch conference, once appeared on the Merv Griffin Show, and, because of his credentials, shows up in newspapers all over the Northwest whenever there is a Sasquatch sighting. Grover Krantz is not known for his field work, but he may still complete construction on an ultralight helicopter that he keeps under a tarp in his driveway. He has already spent nearly ten thousand dollars on a breadbox-size infrared heat-seeking device for the helicopter. He plans to use it to search the woods for a freshly decomposing Sasquatch corpse during the spring thaw. “The scientific community is always saying give us more serious scientific evidence, more dermal ridges, but it's left to the rugged individual to go out and do the research,” he says.

Lately Krantz has been receiving criticism from the other side. Several Bigfoot investigation groups insist that one of his main suppliers of Bigfoot footprint casts—Paul Freeman, a lone-wolf investigator in Walla Walla, Washington—is a hoaxer. Before meeting Krantz, I drove into Walla Walla, at the foot of the Blue Mountains, to see Freeman's evidence first hand. When I arrived at Freeman's house, he was having a yard sale. In 1989, Freeman was fired from the forest service for talking too much about Bigfoot, and he has supported himself since with frequent yard sales, part-time managing of a mobile home park, and the occasional Bigfoot presentation at local malls. He and his family have had to move several times, because of ridicule. He has also suffered physically, and, a few years ago, broke the arch in his foot while hunting in the woods. Last April, he managed to videotape one of his sightings, though the tape was blurry, because in the excitement he forgot to push the zoom button. When I last spoke with him, he was waiting to hear from Scotland Yard about some hair and feces samples he had sent them and to have the video tape computer enhanced. In its current state, the video mostly shows-except for a tiny blur at the dark edge of a clearing-the floor of Freeman's truck as he wrestles with the door; on the sound track Freeman, out of breath, whispers, “Goddamn, there it is! I've been waiting for this son of a bitch! This is it for sure!”

In his garage, Freeman showed me the dozens of footprint casts and odoriferous hair samples that he keeps on hand. (He keeps the remainder of his collection in various rented storage spaces throughout the Walla Walla area.) He also showed me two life-size Sasquatch replicas he had a sculptor at nearby Whitman College build to his specifications. “The lady who made them, she put the wrong eyes in it, but I'm having new ones made,” Freeman said. The female had noticeably large breasts, just like the female in the Patterson film, and she was roughly Freeman's size. “You could fall in love with her,” he said.

During the garage sale, we discussed the competition among Bigfoot experts. “I'll tell you, it's impossible to prove by yourself anyway, but the people looking are cutting each other's throats,” he said. “I always wonder, Why can't we work together? I mean, we're a special little group of people, all of us trying to prove this animal exists. Myself, I just keep plugging along, figuring I might get some real good video someday, but I don't have to prove anything to anybody. My son's seen it, so now we just live with it, though I guess I'd love to see the thing protected. It's one of the greatest mysteries in the world and I'm just glad to be a part of it.”

A few summers ago, there was a sighting on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Spalding, Idaho, just across the Washington border, in the foothills of the Bitteroot Mountains, and Professor Krantz drove there in a minivan with some plaster-of-Paris for footprint casting and two anthropology graduate students-Mark, twenty-eight, who had seen the Patterson film sixteen times, and Markku, thirty-one, a former soldier from Finland. I had arrived in Krantz's office moments after the sighting had been called into him, and I persuaded him to let me come along. When we pulled into the parking lot of the Nez Perce National Historic Park, there were several people speaking to the local newspaper reporter and to Don Tyler, chairman of the anthropological department at the University of Idaho. Tyler had already briefed Krantz by phone on the character of the witnesses, so Krantz, lurched over, lit a cigarette, and immediately began nonchalantly interviewing them. All at once, they pointed to the top of a hill overlooking the Clearwater River. A few minutes later, a man pulled up, jumped out of his car, and ripped open some pictures that he'd just developed. “These will prove it,” an old woman said. There were several photographs of the hill showing a fuzzy little black dot. Krantz didn't flinch. “You wouldn't expect it to be very good without a telephoto lens,” he said.

Walking up the hill, Krantz was optimistic. “If it's a big bugger, it could weigh up to a thousand pounds,” he said. Suddenly, Markku shouted out. He kneeled and pointed at some tracks. “Its stride is one hundred and twenty to one hundred and forty centimeters,” he said.

“O.K.,” Krantz said. “Could be an adult female or a young male, and it would have roughly the same length of step as the creature in the Patterson film. So far, though, I can't rule out human feet.” he continued pacing the hill, tracking his own thirteen-inch feet along the way. “You could fake it, but it's hard,” he said. “Also, if it was a fake you would have better pictures.” Somebody spotted a dead cow on the next hill, and Krantz found the imprint of a horse's hoof. Then, Mark discovered another set of tracks. Krantz shouted, “O.K., here we go! This is the real thing. It's a little tight—only thirty-four inches in the stride—but it's real.”

Wrapping up the investigation with some notes and a few more interviews, Krantz went back to the parking lot to thank the other witnesses, leaving a plaster cast of a Patterson footprint as a combination thank you-business card. I followed him to a gas station for Cokes and analysis. It would be lost and looking for a place to settle,” he theorized. “It may be a young Sasquatch looking for a territory of its own, or being driven away by a forest fire down south. It's just a pity there was nothing good enough to cast.” He added, “You've come a hell of a lot closer to one than most people. You've seen what most certainly was a Sasquatch.”

When it comes to deciding exactly where to encounter a Sasquatch face-to-face, Cliff Crook prefers the forests around Mount Rainier. Every year, around Labor Day weekend, he drives there from his home, outside Seattle, and spends a few days looking around and just waiting. There have been a couple of what he considers quality sightings near Rainier over the past few years-one by a group of mushroom pickers along the banks of the Nisqually River, the other by a group of people staying at a lodge just outside the western entrance of Mount Rainier National Park, both around Labor Day weekend. “I don't know what it is; I just like it up there,” Cliff says.

In contrast to, say, the , who consider the woods so many topographical quadrants to conquer, Cliff is more of a Zen Sasquatch hunter: he tries to get in touch with the Sasquatch's woods. Unlike Rene Dahinden, say, Cliff does not carry a gun. He says this is because when he first encountered a Sasquatch, as a young boy, he was struck by the Sasquatch's apparent dislike of acts of violence. When a boy he was with threw sticks at the Sasquatch, it responded by saying, “Argar largar,” which Cliff translates to mean, “Don't do that again.” Since then, Cliff has become protective of Bigfoot-so much so that when I asked him exactly where around Mount Rainier he was likely to be before Labor Day, he was politely cryptic. Nevertheless, I had an idea of where to find him, and I knew I'd recognize his old maroon Datsun, with the “i brake for bigfoot” bumper sticker. So, on a fall weekend, just before Labor Day, I packed up a tent and went searching for Cliff while he was searching for Bigfoot.

After looking in vain for a few hours at various trailheads and at the lodge Cliff investigated last year (“I really thought it was just a bear,” the owner remembered. “But then I heard that combination bear-growl and pig-snort that Cliff tells me they make”), I finally picked a trail whose terrain closely matched all that Cliff had told me about his favorite investigation areas. I had never gone camping in the woods alone before, and as I walked my first mile I realized how difficult it was going to be to find Cliff in such dense forest. I began in a low, marshy area, gurgling with little streams, and dark with towering Douglas fir. I climbed a long hill to drier ground, and, in a while, splintered redwood spilled onto the trail like hot coals. Gory, bulbous growths sprouted from the sides of lodgepole pine trees, and ferns and vines invaded the dark-green horizon. I was looking for what I thought Cliff would be looking for tracks, large piles of scat, and branches twisted at heights of seven feet and up-when I thought I heard a sound. I grabbed my binoculars but saw nothing. A second later, a golden-mantled ground squirrel jumped out of nowhere to scare the hell out of me. In an hour, dusk was on its way and I had seen only two othercamp- ers,both heading off the mountain. I crossed ĚýKautz Creek, which was roaring with glacial runoff. On the other side, in the sandy bank, I lingered over the imprint of a single large boot.

At 1:20, I awoke from a light sleep absolutely convinced that something was breathing outside my tent. By 2, motionless except for a pounding heart, I was debating two escape strategies: (1) curling up in a ball or (2) screaming and running down the hill to the ranger station.

At around five in the afternoon, as I started up yet another hill, the trail began to follow a creek called Devil's Dream. In a few hundred feet, the creek dropped suddenly from the trail and into a dark ravine so deep I couldn't see the bottom. I kicked a rock, watched it fall off into blackness, and heard it land many seconds later with a crack! At that instant, I realized that these steep cliffs and the nearby water and the texture of the woods made this just the kind of place Cliff believes to be a prime Sasquatch investigation area. I set up a tent nearby, made dinner and had a beer. Above me, in and out of clouds, the glaciered pinnacle of Rainier appeared like an apparition in the cracks of the ceiling of trees; there was a little less than half a moon. By now resigned to not finding Cliff, I tried to lose myself in my field guide to wildflowers, but it was too dark, and I was getting nervous, so I zipped up the tent flap and hoped for rest.

At 1:20, I awoke from a light sleep absolutely convinced that something was breathing outside my tent. By 2, motionless except for a pounding heart, I was debating two escape strategies: (1) curling up in a ball or (2) screaming and running down the hill to the ranger station. I think it was about 3 when I found the courage to look carefully outside with my flashlight. I scanned the face of the darkness, startling single trees. Daylight was still far away, and I knew at this point that I could never cut it as a Bigfoot investigator. At last, near dawn, looking flashlight-less out my tent, I saw it-staring at me and standing completely still about fifty feet from my camp. As more light fell, I realized that it was a man, and then that it was a man I knew, and then, though I knew it couldn't possibly be possible, that it was the statue of Father Duffy, three thousand miles away in New York's Times Square. At around 5 a.m., I took a big gulp and watched the cold gray face of Father Duffy melt into the decaying corpse of a weathered old pine.

After I was home, I got a call from Cliff. He said that I was pretty close to where he had been that night, and he asked if I'd seen the cougar roaming around. He was upbeat, having just wrapped up an investigation: he had successfully linked a set of tracks that he'd initially thought to be those of a female Sasquatch to a hermit who lives in the woods outside of Seattle and is known as the Ice Man because he walks barefoot through ponds and streams in the winter. The next day I got a call from RenĂ© Dahinden who had some information on the sighting that Grover Krantz had taken me to in Idaho. “It was a fake,” he said. “I heard from a guy in L.A. that it was just a man in a suit.” He added, “As a group, we know nothing about Krantz as a person. We know nothing about his upbringing. I would like to know about his father. You know, how many brothers, how many sisters, some background-because I'll tell you, he certainly has a problem trying to be somebody.”

A few days later, I talked to Ray Crowe, who seemed to be having a little bit of a crisis. “I don't know if you've thought it through,” he said, “but if you were running this whole thing as a business and if after twenty-five years you didn't have any results, then you'd begin to chop heads. So I'm assuming what they've all done before me is wrong. They go to these sightings and investigate them and they want to study the people who saw it, put `em through the lie detector. But I'm thinking that maybe you're better off sitting up on a lonely ridge waiting and looking. I don't know, I'm just looking to break away. I only wish I could make more damn money on the whole thing. I think I made thirteen dollars and fifty cents last night and it cost twelve dollars to rent the extra chairs.”

The reason for extra chairs was a speaker named Jim Hewkin, a retired wildlife biologist for the state of Oregon. When Hewkin spoke, he jumped over the proof part of the Sasquatch issue and right into Sasquatch habits, the way W.B.O. members like their speakers to. “We don't know much but we're beginning to draw pictures,” he said, “and we've started to frame out something that a Bigfoot is like. We're probably looking at ourselves about four million years ago, living off the land with no tools, probably talking about the Dark Ages. And then we changed in one direction, and the Bigfoot kept going back into the rough country and living off the land in the roughest kind of habitat there is. And it makes you think again: Well why? Must have been man that caused that. Probably a lot of friction between man and Bigfoot in those days and he just spread out. I'm getting into the kind of scientific part where archaeologists and people who study this, the past, should be, but today we have to look at all the animals there are that we know and find all the evidence there is that's logical, true, factual, listen to anybody that has anything to say, separate the wheat from the chaff. There's a lot of chaff. And don't let your imagination go too wild when you're out there alone, looking around for signs. You think you'll find a sign. You hope you find a sign, and maybe you do.”

Ěý

Postscript

Since I researched this story, a few years ago, there have been numerous possible sightings of Bigfoot and some more possible tracks but no definitive finds. In addition, the cast of hunters and Bigfoot enthusiasts has changed somewhat. Last I heard, Ray Crowe has sold his bookstore and closed up his museum, though he still publishes a newsletter and hopes one day to open up the museum again. René Dahinden continued to keep tabs on sightings in his area and to stay in contact with hunters throughout the Northwest, but in his final years—he passed away in 2011—he didn't get out into the field as much. Grover Krantz died in 2002. I never heard from Cliff Crook after I last saw him near Mount Rainier. Datus Perry passed away a number of years back, which was sad news in the Bigfoot community because even Bigfoot hunters who didn't feel his sightings were properly substantiated enjoyed seeing him and talking with him at Bigfoot events, where he was a regular.

One day I was talking to Peter Byrne, still the most prominent Bigfoot hunter; he has searched full-time for Sasquatch on several occasions, at one point spending five years at an operations base on Mount Hood. I had last talked to him in the summer of 1997 when he had just wrapped up his Mount Hood investigation. At that point he was considering starting up another one. As it turned out, even he had downsized his operations: he still goes to check out sightings on occasion, but he is taking it easy at the moment, taking the time to write and travel. It was still early in the summer when I talked to him, but he said that in general the Bigfoot investigation field is slow at the moment. “It's been extremely quiet,” he said. “There's been nothing really.”

Robert Sullivan is the author of Rats, A Whale Hunt, and, most recently, My American Revolution, among other books. He lives in New York City.

This story originally .