Can Sylvia Earle Save the Oceans?

The marine biologist has done things in the ocean that would scare most people senseless. She's been alone in total darkness thousands of feet down, hovered under a Russian ship as it pinged her submarine, and been charged by huge sharks. But one thing does frighten her: the dire state of our overfished and polluted seas, something she spends every waking hour trying to change.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Almost the first thing Sylvia Earle said to me was, ŌĆ£The oceans are dying.ŌĆØ

We were at a small dinner in Manhattan last fall, celebrating the New York premiere of a documentary about her called . As the worldŌĆÖs best-known oceanographerŌĆöSylvia is to our era what Jacques Cousteau was to an earlier oneŌĆöshe feels a heavy responsibility. In her lifetime, she has seen the ocean damaged in ways humans never thought it could be. The ongoing disaster leaves her mournful, desolate, and sometimes scary to talk to. Since her first dive, in a sponge-diverŌĆÖs helmet in a Florida river when she was 16, she has spent 7,000 hours, or the better part of a year, underwater. In the depths, swordfish and bioluminescent fish and humpback whales in midsong have swum by her, done a double take, and stopped to check her out. From her lifeŌĆÖs experience, she has become no longer really terrestrial. She is like a super-apex sea creature that has somehow wound up on dry land and is walking around and telling everybody about the terminal ruin humans are inflicting on her home.

Every day more signs appear that seem to prove her dire predictions right. She sees portents of human beingsŌĆÖ alteration of the oceans visible to no one else. Our leavings are now everywhere: she knows that off California, about 10,500 feet down, a solitary white plastic patio chair sits on the bottom as if its occupant had just gotten up to turn the steaks. She watches sea life being destroyed from every direction, between over-fishing and pollution and rising temperatures, with the oceanŌĆÖs chemistry going to hell and reef paradises that she used to love now dead and rotting. As Pope Francis noted in his recent encyclical on climate change, ŌĆ£Coral reefs comparable to the great forests on dry land ŌĆ” are already barren or in a state of constant decline.ŌĆØ Sylvia began warning about that nightmare decades ago.

Last May, a small story on page six in The New York Times that Chinese ships, as observed by Greenpeace, had been fishing illegally off the west coast of Africa. The coastal waters of China have been so gravely depleted that Chinese vessels must now go much farther from home. Off Africa, their bottom-trawling methods ripped up the ocean floor and took fish without regard for limits or species, Greenpeace said. China responded by saying that its ships provided fees and other benefits to the African countries in whose waters they fished. The observed offenses occurred at the same time that some of those countries were in near chaos, fighting the Ebola virus. This story, we may imagine, contains a sketch of the future that Sylvia is talking about.

Video courtesy of Kip Evans from

When the adventurer Thor Heyerdahl crossed the Pacific by raft in 1947, he saw no trash. Today, garbage patches the size of small countries rotate in the centers of various oceans. A in 2009 found that cigarette butts were the most common debris, with plastic bags second. Of unknown danger are the much smaller pieces of plastic that infuse the seas and probably will forever. Marine animals ingest plastic fragments and die. Lost or discarded nylon fishing nets and monofilament longlines drift endlessly, catching and killing hundreds of thousands more every year. According to , a detritus-filled part of the Pacific holds six pounds of floating trash for every pound of natural plankton.

In the Florida Keys and the Caribbean region, as much as 80 percent of the coral reefs are dead or in severe decline as high water temperatures bleach them. Excess CO2 in the atmosphere leads to ocean acidification, which is already destroying the shells of sea snails and other tiny creatures near the base of the oceanŌĆÖs food chain. When CO2 in the atmosphere exceeds 560 parts per millionŌĆöa level we are likely to reach by the end of the 21st centuryŌĆöall coral reefs, the incubators of life, will eventually disappear. Perhaps 70 percent of the oxygen on the planet comes from photosynthesis taking place in organisms in or near the few sunlight-rich feet of water at the oceanŌĆÖs surface. The ocean supplies about two of every three breaths we take. What climate change will do to that oxygen production is ominous and uncertain.

Most of the big fish in the oceans are gone. ŌĆ£We have to stop killing fishŌĆØ was the second thing Sylvia said to me. Populations of larger predators like cod, marlin, halibut, and sharks are at less than 10 percent of their numbers from 70 years ago. WeŌĆÖre now taking swordfish that have barely reached the breeding stage. ŌĆ£Eating these fish is like eating the last Bengal tigers,ŌĆØ she says.

Her response to the plummeting fish numbers and to the crisis in general is to establish ŌĆöprotected places in the ocean where dumping, mining, drilling, fishing, and all other forms of exploitation are prohibited. She has picked out almost 60 places for this status, and she dreams of having 20 percent of the ocean fully protected by 2020. Right now about 2 percent has that protection. A big victory in this quest came in 2006, when she happened to sit at the same table with President George W. Bush at a White House dinner, and helped influence him to create a 140,000-square-mile, fully protected marine national monument around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Establishing many more Hope Spots is the principal goal of SylviaŌĆÖs life.

And yet, somehow, thereŌĆÖs also a sense that nobody is listening. Sometimes, SylviaŌĆÖs sea blue eyes have the same gentle sorrow with which wise and kind aliens look at foolish earthlings in movies. ŌĆ£Many people I love have no idea of the trouble weŌĆÖre in,ŌĆØ she says. When she started talking about the decline in fish populations, 25 years ago, the number of bluefin tuna remaining had fallen to about 10 percent of the total when the species was healthy. Today only about 3 percent of bluefin tuna remain. She keeps on telling us; we keep on not listening. She is like a bright red stop vehicle immediately light thatŌĆÖs been blinking on the dashboard for 25 years. But the car seems to keep going, so we keep on driving.

Last April, I saw Sylvia give a talk and a video presentation in Tampa. The event was in a historic-landmark theater with an old-fashioned marquee that puts performersŌĆÖ names in lights, and SylviaŌĆÖs was on top, above that of her fellow speaker, a woman biologist known for her studies of the forest canopy. The audience, about three-quarters female, cheered when Sylvia took the stage with her arms uplifted in a touchdown gesture. She wore black slacks, dark glasses (because of a flu-like case of ŌĆ£airport-itis,ŌĆØ she said), and a dress jacket of aqua blue, her signature color.

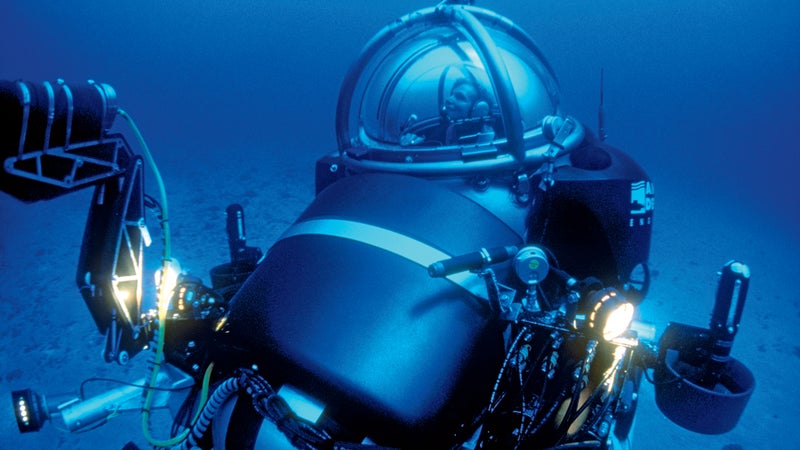

ŌĆ£You can do it, too!ŌĆØ was the inspirational theme. Her often told autobiography rolled out: how she earned degrees in marine botany from Florida State University and Duke at a young age; how she went on a round-the-world oceanographic cruise in 1964 with 70 other scientists and crew members, all of them men; how she became a national celebrity in 1970 when she led a group of five women scientists in an experiment living in a capsule underwater for two weeks on a coral reef; how she served as the first woman chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for 18 months in the early nineties but resigned because of her greater sympathy for fish than for the fishermen helped by the NOAA; how she founded companies to build mini submersibles, one-to-five-person crafts that can descend thousands of feet; how Time magazine named her a Hero for the Planet in 1998.

On the subject of saving fish from overfishing, she showed a frightening clip of herself in 2012 swimming next to a school of menhaden as it was being netted and sucked up into a factory ship for processing into omega-3 fish oil. The video bounces with the motion of the waves as crewmen in yellow slickers yell and wave frantically at this small, agile, determined, wetsuited woman to get out of the way. How she avoids being netted and inhaled into the maw herself is not clear. ŌĆ£When that school was captured, I felt as if a piece of me was ripped out of the ocean,ŌĆØ she told the Tampa audience. They cheered her throughout and at the end of the evening rose as one in a standing ovation.

She then sat and signed copies of her latest book, , for more than two hours. Such devotion of fans to their star, or vice versa, I had never seen. To some, Sylvia gave five or ten minutes, listening to their personal stories and posing with them for photographs. People said, ŌĆ£You have been my hero since I was a little girl!ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£I knew Dr. Harold Humm at Duke, and he adored you!ŌĆØ Theater staff turned out some of the lights, and the signing progressed in the near dark until someone found a lamp. Each inscription received her careful attention. At the end of the line, an auburn-haired young woman waited patiently while the minutes and then hours went by. When her turn finally came, she crouched by the signing table. Leaning her face close to SylviaŌĆÖs, she said, ŌĆ£I want to be you.ŌĆØ

Sylvia smiled and said, ŌĆ£Just be yourself.ŌĆØ

The worsening emergency keeps Sylvia on the road for more than 300 days in a year. I felt lucky whenever she gave me an extra moment. Over the holidays, when she was taking a short travel break at her main residence in Oakland, California, I flew out there. This time we met in front of San FranciscoŌĆÖs Aquarium of the Bay, where she had an appointment to talk to the director about his plans to add mini-submarine excursions for visitors. Sylvia brought an entourageŌĆöher daughter Liz Taylor, who now owns and runs (DOER), a marine consulting and engineering company Sylvia founded; Laura Cassiani, the COO of SylviaŌĆÖs foundation, ; Jane Kachmer, then a consultant working with Sylvia┬Ā(and now the foundationŌĆÖs CEO); Colette Cutrone Bennett, then director of sponsorship for Rolex, which has backed some of SylviaŌĆÖs enterprises and for which she has done ads; and Heather, whose last name I didnŌĆÖt catch, also with Rolex. Heather and Colette, both knockout blondes, had flown in from New York the evening before and were flying out that afternoon. Colette had sat next to Donald Trump at a recent equestrian event in Palm Beach and had talked business, and he gave her his phone number. She discovered that she had misplaced it, however.

As we entered the building, Sylvia saw, first off, an exhibit of a big cylindrical tank full of anchovies swimming around and around. It stopped her. She looked at it for a while, then shook her head. ŌĆ£No,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£This is not the way to see these animals. This makes them look like a mass. They are not only thatŌĆönot just some endlessly abundant school. Each one of these fish is also its own individual being.ŌĆØ

At a display about shark attacks, she frowned again. ŌĆ£Sharks do not attack people,ŌĆØ she corrected, standing under a surfboard with a large bite out of it. ŌĆ£Sometimes, extremely rarely, they mistake a human for food. TheyŌĆÖre not these evil, malevolent creatures, although we like to think so, in order to thrill ourselves. If that description fits anybody itŌĆÖs us, when we hack the fins off the living animals for shark-fin soup and then throw the mutilated sharks back in the water.ŌĆØ

Sometimes, Sylvia's sea blue eyes have the same gentle sorrow with which wise and kind aliens look at foolish earthlings in movies.

She didnŌĆÖt really perk up when the museum director led us through the clear glass tunnels that make visitors feel as if they are walking under the sea. But when he led us backstage and upstairs, onto catwalks atop the tanks through which the tunnels pass, she became absorbed in looking down at the fish, and she was no longer with the group when we emerged into the aquariumŌĆÖs inner hallways. ŌĆ£Maybe she jumped in,ŌĆØ someone suggested, and when she caught up she said she had wanted to. During the meeting that followed, she returned to her basic mood of enthusiasm and optimism, bobbing back up like a cork with her touchdown gesture and saying ŌĆ£Yes!ŌĆÖ That was her reaction when the director announced his plan to make the aquarium a ŌĆ£sub hubŌĆØ for mini subs transporting ŌĆ£citizen scientistsŌĆØ and wealthy donors on research trips into San Francisco Bay.

Suddenly, she thanked everyone, and she and her entourage said goodbye and hurried off to cabs. Another meeting awaitedŌĆösomething at the Autodesk Pier 9 facility with Rolex. I went back to the anchovy display and stared at it for a while. Although I tried to pick out individual anchovies and identify them the next time they came around, I could not say I succeeded. In fairness, one anchovy really does look a lot like another. But as I noticed this one flare its gills or that one rise to take something off the surface, maybe I got her point.

Sylvia has been married three times: to John Taylor, a zoologist; to Giles Mead, an ichthyologist; and to Graham Hawkes, an engineer. Reporters have always asked her more about her personal life than they would have asked a man in her position. During the early days of her fame, stories about her played up this angle and featured photos of her American-girl good looks and wide, gleaming smile.

She had a son and a daughter with her first husband, and a daughter with her second. With Hawkes, her third husband, she had no children, but together they founded two companies devoted to the design and building of mini submarines. In Sea Change, an autobiographical book published in 1996, she included a photograph of Hawkes wearing a tuxedo and piloting a mini sub. This was perhaps a reference to HawkesŌĆÖs role as a villain in the James Bond movie For Your Eyes Only, in which he fought and lost a submarine battle with Roger MooreŌĆÖs Bond. Hawkes and Sylvia divorced in about 1990; she has said he was more interested in treasure hunting than in science. (On her own she started DOER in 1992, and he is not involved with the company.)

In truth, SylviaŌĆÖs life is so wide-ranging and complicatedŌĆöso oceanicŌĆöas to be a challenge to describe. The swerve she made into the mini-sub business puzzled many of her scientist colleagues. Liz Taylor, head of DOER, does not resemble the late movie star of the same name. This Liz has strawberry blond, wavy hair, and an engineerŌĆÖs calm, analytical poise. Two days after the aquarium visit, I was supposed to meet Sylvia at DOERŌĆÖs headquarters in Alameda for a tour. When I arrived she wasnŌĆÖt there, so Liz showed me around.

DOERŌĆÖs factory, in a dockside hangar next to AlamedaŌĆÖs harbor, is big enough to hold a small ocean liner. Over the years, DOER has sold unmanned remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) to many customers in government, business, and science, and to several foreign navies. The factory resembles a deep box of giant Legos. Liz pointed out the six-foot-across bubbles of clear acrylic that the submariners sit in, and the subsŌĆÖ many-hinged mechanical arms (in ads, these arms have had Rolex watches strapped to them), and the container-size support modules, and the smaller submersible robots that can work on offshore oil rigs and unclog municipal water tunnels. The pieces of equipment suspended here and there in the hangarŌĆÖs twilight gave the high-walled space an undersea quality.

DOERŌĆÖs most ambitious goal is to build three-person submersibles that can travel to any depthŌĆöall-access subs. One design would be able to descend quickly, the other more slowly. The research has been completed and the project is ready to go, but funding for a test model is not yet there. The key element of the design, a thick-walled, precision-crafted bubble made of glass rather than acrylic, costs too much for DOER to finance without help. (An estimated price for the two all-access subs is $40 million.) Instead, the company is currently building a pair of subs for $5 million that can go down to 3,300 feet and will be able to accept glass spheres and go deeper when the time comes. When an all-access sub finally is built and scientists can use it to travel the ocean anywhere from top to bottom, the discoveries may be exponentially greater than those made possible 70 years ago by the invention of scuba diving.

Sylvia says some things over and over. When she showed up at DOER and we went to lunch, she repeated a few of them, such as how she persuaded a higher-up at Google to include the oceans in Google EarthŌĆÖs picture of the globe by telling him that, without the oceans, Google Earth was only ŌĆ£Google Dirt.ŌĆØ Another standard: ŌĆ£Fish and lobsters and crabs and squid arenŌĆÖt ŌĆśseafood,ŌĆÖ theyŌĆÖre precious marine wildlife. A fish is much more valuable when itŌĆÖs swimming in the ocean than when itŌĆÖs swimming in butter and lemon slices on your plate.ŌĆØ At refrains like that, my mind wandered. Mission Blue, the movie about her, is mostly engaging, but less so during the parts where one of the codirectors injects himself into the story. Now I found I had some sympathy for this codirector. How does one respond to statements like ŌĆ£the ocean is dyingŌĆØ? The concept is imponderable and upsetting, so of course our thoughts return to that familiar and fascinating subject, ourselves.

I remembered what New York City was like without power or services after Hurricane Sandy. I walked the beaches of Brooklyn and Staten Island and saw that the ocean had indeed gone insane. Houses near the shore were blown out from back to front, piles of sea wrack mounted three stories high, beads of styrofoam lay everywhere along miles of shoreline like an infinitude of dirty snow. Plastic drinking straws, red-and-white swizzle sticks, and brown Starbucks coffee stirrers had been woven into the chain-link fences of softball fields in a mega-profusion I could not have conceived of had I not seen it. The most disquieting aspect of the hurricane, though, was that it had no interest in the spiderweb-thin strands of my own life and concerns, or of anybodyŌĆÖs. Nothing in our cherished plans pertained to it. It spread its destruction, killed or didnŌĆÖt kill, and never bothered about us.

Sylvia and I were supposed to talk more on the following day, but at the last minute a chance came up for her to fly to Chile, where she discussed with ChileŌĆÖs president the possibility of creating a Hope Spot in the Pacific Ocean around Easter Island.

Almost half a century ago, before being on the world stage had crossed her mind, Sylvia made her reputation as a scientist with a now classic Ph.D. dissertation about marine algae (seaweed), entitled ŌĆ£.ŌĆØ Phaeophyta are the brown seaweeds. There are also green seaweeds and red seaweeds. By the time she was 30, Sylvia had learned more about the brown seaweeds of the Gulf than anyone had ever known. Doing all the collecting herself, without any grants or subsidies, and using scuba equipment, then still in its early stages as a research tool, she amassed specimens by the thousands. The eastern Gulf was her region of study, because she lived in the coastal town of Dunedin, near Tampa, as a girl and young woman. Of the tens of thousands of marine algae specimens she has collected in her life, about 20,000 are now in the botanical department of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Algae do not sound exciting and call to mind ponds or poorly tended swimming pools. In fact, algae are the principal flora of the oceans, the planetŌĆÖs workhorse photosynthesizers and oxygen producers. Under healthy conditions, algae species exist in rainforest-like abundance. They can be tiny single-cell organisms or 150-foot-long kelp; mostly they are hand size or smaller. Prochlorococcus, a single-cell blue-green alga, or cyanobacteria, that is perhaps the most abundant photosynthesizing organism on earth, produces an estimated 20 percent of the planetŌĆÖs oxygen supply. SylviaŌĆÖs thorough catalog of phaeophyta showed what a thriving Gulf looked like. Pollution, oil spills, and dredging destroy algae, hurricanes rip them from their environments and kill them, and nitrate pollution from fertilizer runoff enhances the growth of certain algae at the drastic expense of others. Like everything else in the ocean, the seaweeds are under assault. In retrospect, SylviaŌĆÖs study serves as an essential reference point for what the Gulf was like before late 20th-century development came along.

Her dissertation is also a work of art, as I discovered when I read it; excitement and romance infuse its scientific language in a hard-to-explain way. She did all the drawings herself. I asked her if sometime she would show me a few of her specimens at the Smithsonian, and one afternoon, when she happened to be in D.C., she met me there. If youŌĆÖve seen her before, as I had, it can be a surprise to remember that sheŌĆÖs five feet, three inches tall and 80 years old; she appears to be simply herself, and not of any particular size or age. Her walk is easy and casual, as if she almost disdains to do it. The only time she moves like her real self is when sheŌĆÖs swimming. With her that day was Robert Nixon, a producer and codirector of Mission Blue. (HeŌĆÖs not the codirector who kept intruding in it.) As they came up the steps, they were talking about the mesh size of squid nets. She was saying to Nixon that the best size of mesh in squid nets is no nets at all.

Three scientists of the Smithsonian greeted us just inside: James Norris, David Ballantine, and Barrett Brooks, all of them experts in marine botany and equal in their awed deference toward Sylvia. She had set up the afternoonŌĆÖs viewing session with a phone call to Norris, a cheery man with glasses and a neatly trimmed white beard. He said he had an exhibit he wanted her to see, and he led us to a display case. Pointing to a piece of coral covered with a reddish lichen-like growth, he said, triumphantly, ŌĆ£This is the deepest-dwelling alga ever foundŌĆö278 meters!ŌĆØ

Sylvia cocked an eye at it and nodded in approval. ŌĆ£These deepwater photosynths are getting short shrift in our assessment of the O2 productivity of the oceans,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£At this depth, itŌĆÖs photosynthesizing with one-tenth of one percent of the sunlight available at the surface. How can it live? We know almost nothing, really, about deeper-dwelling ocean life.ŌĆØ

I had made the mistake of telling Sylvia that I liked to fish. ŌĆ£Why do you enjoy torturing wildlife?ŌĆØ she asked me.

Through back hallways, we made our way to a cavernous inner room where elbow-high cases of flat drawers stretched into the distance. At a place where the fluorescent lights were brighter, tan paper folios had been laid out on the case tops. Sylvia opened the folios carefully, one by one. Here was an alga called Avrainvillea sylvearleae, unknown to botany until she discovered it on some rocks in two meters depth near WilsonŌĆÖs Pier off the town of Alligator Harbor, Florida. Here was Padina profunda Earle, found attached to limestone and fine shells in 60 meters depth 19 miles off Loggerhead Key in the Dry Tortugas. ŌĆ£In the water, itŌĆÖs a translucent alga, like glass,ŌĆØ Sylvia remarked. Here was Hummbrella hydra Earle, found in 30 meters depth off Chile, which she named in punning tribute to her beloved mentor, marine botanist Harold Humm. ŌĆ£In their habitat, these branches look like pink umbrellas turned inside out,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£Very Dr. Seussian.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖre all such beautiful specimens,ŌĆØ Barrett Brooks said. ŌĆ£You dried and pressed all of them yourself, and you generally didnŌĆÖt use formalin.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I never liked formalin. I mean, itŌĆÖs embalming fluid! Think of how much of that stuff I would have in my system by now.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs great you didnŌĆÖt, because formalin scrambles DNA,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£If you had, we couldnŌĆÖt do DNA sequencing on your specimens.ŌĆØ

As the folders opened, every specimen revealed a different structureŌĆösome broad-leafed and fan-like, some resembling stick insects or needlework sewn microscopically fine. She explained how an alga called Phaeostroma pusillium, which she found in the Gulf, constitutes probable evidence for the nonexistence of Florida during the high-water Pleistocene era, because the alga is also found in the Atlantic, from Georgia to Rhode Island. ŌĆ£To most people, all these beautiful plants would probably just be the gunk you pull off your boat propeller,ŌĆØ she said.

Tactfully, Nixon interrupted to say that they now had to rush to SylviaŌĆÖs next appointment. Their schedule had got backed up because their previous meeting had gone on too long, Nixon said. It had been with the vice chairman of land and natural resources of Tanzania, who had talked at length to Sylvia about his countryŌĆÖs problem of fishermen who fish with dynamite.

ŌĆ£That happened to me!ŌĆØ Norris said as he walked us out. He had been diving at about 30 feet, collecting algae off the southwestern coast of China, when a fisherman threw three sticks of dynamite into the water nearby. The explosion tore off all his scuba gear, crushed his chest, rearranged his internal organs, and blew out both his eardrums. He would have died if not for the extraordinary efforts of the U.S. Embassy, a British Petroleum helicopter, and a French diving physician who was in the area. After a few days in a hospital in Hong Kong he flew to Washington, where he spent more than a year in rehab. Eighteen months after having been dynamited, Norris was diving again.

Sylvia shook her head in sympathy. ŌĆ£Dynamite fishing is a real problem nowadays,ŌĆØ she added. ŌĆ£When all the catchable fish are gone, people use dynamite to bring up any little ones who might be left.ŌĆØ She and Nixon then said goodbye to the scientists and to me, hurried out the front entry, and caught a cab. The four of us, as if in her wake, stood in the lobby and talked about her. ŌĆ£What impressed people about Sylvia from the beginning was that she was a scientist, not a technician, making these dives,ŌĆØ Norris said. ŌĆ£In the past, a lot of our ocean science had been like flying over the Amazon in a plane looking out the window and not getting down on the ground. But Sylvia always pushed to go down and see what the heck was going on for herself.

ŌĆ£And sheŌĆÖs sure not exaggerating the oceanŌĆÖs problems, I can tell you that.ŌĆØ

Sylvia is from New Jersey originally. Her parents had a small farm near the Delaware River in the southern part of the state. Her father, Lewis Earle, an electrician who worked for DuPont, could build or repair anything. Sylvia gets her engineering skills from him. Her mother, Alice Richie Earle, loved the natural world and showed interest rather than alarm when Sylvia came back from a nearby creek with animals she had found. Sylvia was the sixth of their seven children and the only girl. The couple lost their first four, all of them boysŌĆötwo in infancy, another to an ear infection at the age of nine, and their oldest in a car accident. Such tragedies could have destroyed a marriage, but the Earles kept going.

The family moved to Dunedin in 1948, when Sylvia was 12. At that time the town was an undeveloped, almost frontier place. Their house had the Gulf of Mexico in its front yard. Sylvia first used scuba gear at the age of 17ŌĆöJacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan had invented the equipment just ten years earlier. She went all over the Gulf, using her familyŌĆÖs 18-foot outboard or hitching rides with shrimp boats or Navy divers, always in search of new seaweeds. She can describe vanished Florida in a way that makes you mournŌĆöthe inland freshwater spring lakes ŌĆ£as blue as morning glories,ŌĆØ the reefs (now mostly dredged up along the urbanized coasts, and gone), the groupers that watched her work and got to know her and would have followed her up onto the shore if they could have. (ŌĆ£Almost all the groupers have disappeared. They were friendly and curious, like Labrador retrievers, and they also happened to be delicious.ŌĆØ) She pronounces the complicated Gulf Coast names without a pause, from the Tortugas to Apalachee Bay, Pass-a-Grille Beach and Big Gasparilla Island, and the Homosassa and Caloosahatchee and Apalachicola and Tombigbee and Pascagoula Rivers, and so on up to Grand Terre, Louisiana. The wider ocean she travels has its center in the Gulf and radiates outward from it.

The last house that SylviaŌĆÖs parents lived in still belongs to her. It is in a once rural part of Dunedin, on wooded acres that include a lake. When the family moved there, in 1959, the area was mostly orange groves and wild land. By then Sylvia was living elsewhere, but she often returned while doing her algae study, and when she had children she brought them for vacations. The place is still a refuge for her. She told me she would be making another pause in her travels there in early May.

From the outside, the live oaks all around the gray one-story ranch house seem to be pressing it down to about half a story, but inside, the living room is ample and comfortable, with toy stuffed alligators on the couch and idyllic Florida landscapes on the walls. Sylvia led me through a door to the back and then along a narrow boardwalk to a lake that was so smooth and green with duckweed, it resembled the top of a pool table. We sat on a dock. Sylvia was wearing clamdiggers, though she would never dig a clam except for research. I creaked as I sat, but she moved without hitch or creak.

Her father had built the house; the dock and boardwalk were added later. She pointed out the cypress trees he had planted around the lake, which they now buttressed with their large knees. ŌĆ£This lake doesnŌĆÖt have a name,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£Maybe itŌĆÖs just Lake Earle. It used to be tannin colored and beautifully clear. There were bass and gar, and toads along the bank, and flying squirrels in the trees. I really miss the flying squirrels. Runoff from the surrounding development made the water murky and fed the duckweed.ŌĆØ

We walked on the boardwalk through the trees as she pointed out other plantings and improvements her father had made. Her parents come up often in her conversation. She describes them as her ŌĆ£best friendsŌĆØ in the dedication to Sea Change. They were devout Methodists and helped build a church in Dunedin, she told me. I asked her if she goes to church, and she said not really.

We got in her sea blue rented SUV and drove to the Gulf shore. A loud scraping kept coming from under the car. She said it must be a stick and it would fall off soon, but it didnŌĆÖt. When we got to a downtown parking lot, she jumped out, lay on the piping-hot pavement, and pulled out a good-size tree limb with green leaves still on it. After several stops in town, including at a fish store, where she looked with displeasure at the iced casualties for sale, we headed north along the coast. I had made the mistake of telling her that I liked to fish, and she kept asking me why. I said I just loved it because itŌĆÖs my bliss and I want to follow my bliss. That argument had no effect. ŌĆ£But why do you enjoy torturing wildlife? ItŌĆÖs just a choice for you. ItŌĆÖs life or death for them. Why not just observe them without torturing them?ŌĆØ I mumbled an answer about the thrill of the chase.

I asked Sylvia what the death of the ocean would look like. A remote look came over her. ŌĆ£No ocean, no us,ŌĆØ she said.

Her familyŌĆÖs first house in Dunedin had been on Wilson Street. She took us there and pulled over where the street now ends, at a gate you need a card with a magnetic stripe to open. As we peered beyond the gate, high-rise buildings dwindled to a perspective point where a small square of blue Gulf peeked through. A sign offered three-bedroom condos starting at $780,000. ŌĆ£You know that the misconception that fish canŌĆÖt feel pain has been completely disproven, donŌĆÖt you?ŌĆØ she asked. I said yes, I had seen studies in which fish jaws were injected with bee venom and the fish showed pain. I said I knew hooks hurt, having sometimes hooked myself.

Searching for a stretch of original shoreline, she continued out of town, across a causeway, and down a one-lane road to Honeymoon Island State Park. Here the shore was undisturbed and thick with mangroves. We got out and walked along a sandy trail through stands of palmettos, cabbage palms, slash pines, and live oaks. ŌĆ£This is what the open country around Dunedin used to be,ŌĆØ she said. An osprey hovered overhead, sunlight coming through the edges of its wings, and she took pictures of it with the camera she had brought.

At an opening in the mangroves, we came upon a small bite of sand beachŌĆöfinally, the actual Gulf. A widescreen vista opened out. Turquoise shallows marked by brown patches of turtle grass darkened to a deeper blue distance where stacks of white clouds piled up. In the light breeze, the waves did not break but slapped. Striped mullet jumped. We took off our shoes and waded in. Among the prop roots of the red mangroves, a large troupe of fiddler crabs were doing a back step that mimed getting away from us as fast as possible, each crab with one claw raised. At the tide line, Sylvia found tiny pointed periwinkle-like shells, and black snails, and an epiphytic alga that grows mostly on spartina grass, and a marine gnat smaller than this semicolon; we watched it navigate the varicolored grains of sand.

I asked her what the death of the ocean would look like. A remote look came over her. She described gray-green dead zones like the one that exists already in the Gulf off New Orleans, and the disappearance of certain organisms and the rise of others we may not even know of yet, and coastal sterility, and a lack of coral reefs. Some animals, like horseshoe crabs, have survived acidic oceans before, and might again, she said. About soft-bodied animals like jellyfish we donŌĆÖt have enough fossil records to say for sure, but jellyfish are doing OK so far and might do even better in a mostly dead ocean. New Ebola-like microbes might emerge. The planetŌĆÖs oxygen densities might go down and the air become too rarefied in higher places for them to be habitable. Her voice trailed off. She said, ŌĆ£As a species we depend upon the ocean, so the eventual result would be the same. No ocean, no us.ŌĆØ

People often ask Sylvia what they can do. Her focus is not on heading up popular movementsŌĆöshe isnŌĆÖt organizing beach cleanups or fish-market boycotts. She tries to reach the elites. At the end of her in 2009, she told the technology, entertainment, and design invitees in attendance: ŌĆ£I wish you would use all means at your disposalŌĆöfilms! expeditions! the Web! new submarines!ŌĆöand campaign to ignite public support for a global network of marine protected areas, Hope Spots large enough to save and restore the ocean, the blue heart of the planet.ŌĆØ

Her foundation, Mission Blue, has identified 58 Hope Spots around the world, from the Outer Seychelles, off southeast Africa, to the East Antarctic Peninsula, to Micronesia, to the Bering Sea Deep Canyons, the Gulf of California, the Patagonian Shelf, the Sargasso Sea, the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Ascension Island, and the Gulf of Guinea, off the west coast of Africa. Questions about what any particular Hope SpotŌĆÖs protected status would consist of, or how it would be enforced, often remain unexplained. So far, some marine protected areas have had success. , a protected area in MexicoŌĆÖs Baja peninsula, has seen an almost fivefold increase in its biomass since it was created in 1995, and a tenfold increase in big fish. (Sylvia loves Cabo Pulmo and says itŌĆÖs one of her favorite places to dive.)

Any notion that a Hope SpotŌĆÖs purpose is to grow fish for people to catch makes her mad. The sanctuaries are to be places set apart in perpetuity where the ocean can recover, not nurseries for Mrs. PaulŌĆÖs. I once asked her what was the point of creating Hope Spots if the whole ocean will continue to acidify from excess CO2 anyway. She said that the more sanctuaries there are, and the larger amount of ocean they cover, the better the chances for the oceanŌĆÖs resilience, when and if CO2 is under control.

To an extent, her strategy of persuading the elites has worked. People like Gordon Moore of Intel have given a lot of money to saving the ocean, and George W. Bush, when nudged by Sylvia, created the national monument around Hawaii. BushŌĆÖs executive act provided a precedent for Barack Obama, who last year expanded the protected area of the to 490,000 square miles, establishing the largest protected marine network so far. Sylvia says we live in the perfect time to make changes that will benefit the planet for thousands of years. A recent idea, the creation of marine protected areas in the 200-mile , which by international treaty extends from the shoreline of every maritime country, increases her optimism. Most fishing is done within three miles of land, so inshore protected areas (Cabo Pulmo is one example) could have a sizable effect on fish numbers.

But if you donŌĆÖt expect to hang out with the president, make a film, or build a mini submarine, what can you do yourself? When I sent an e-mail to Sylvia asking her advice for ordinary people, she didnŌĆÖt answer, but eventually Liz Taylor did. Her list of recommendations included avoiding plastic drinking strawsŌĆöa good idea, given what I saw after SandyŌĆöbringing your own plate, cup, and utensils to summer barbecues, volunteering at your local aquarium, keeping an eye on changes along the shoreline, helping your state fish and wildlife officers, getting your omega-3ŌĆÖs from algae-based products rather than from fish or krill oil, donating money to environmental groups that educate kids, and stopping the use of lawn chemicals like Roundup weed killer.

Sylvia is a one-in-seven-billion individual, and she encourages other individuals to do what they love and care about the oceans. Collectivity does not seem to be in her nature. But for the ocean to be saved, it seems to me that an enormous, widespread popular movement must rise up someday. In that sense, when Sylvia tells the TED folks to ŌĆ£ignite popular support,ŌĆØ she is handing off the hardest part of the job. People can be induced to care about lovable, wide-eyed animals like seals, or to donate to dolphin rescue, or to visit and buy souvenirs at places that rehabilitate stranded sea otters and turtles. But getting across the real, immense, nonspecific, unsexy fact of the oceanŌĆÖs impending death in such a way that billions of people will care and want to do something about it is a problem nobody yet has solved.

Sylvia has not persuaded me to stop fishing, but I have decided to use only fly-fishing equipment from now on. And since I met Sylvia, I have eaten almost no fish. The sight of sushi now embarrasses me. It is likely that big fish like swordfish, tuna, cod, and grouper will soon disappear from the sea, or from our diets, or both. We might as well completely stop eating those fish now.

Driving again in SylviaŌĆÖs sea blue SUV, we went up to Tarpon Springs to see the old sponge-boat docks. She said they looked picturesque, but in the old days, when there were actual sponges drying all over the place, the smell was unbearable. By now the afternoon had moved into rush hour. She was still thinking about my fishing and asked me how hooking an animal in the mouth and watching its desperate struggles could possibly be enjoyable. I explained about the relatively non-injurious aspects of fly-fishing, how it uses only a single hook, etc. She asked why I didnŌĆÖt quit fishing entirely if I wanted to do less damage to the fish. Approaching Dunedin, we turned off the highway and onto a back road. She said, ŌĆ£Now I want to show you my parentsŌĆÖ church.ŌĆØ When I didnŌĆÖt answer, because I was still thinking of an answer to her previous question, she said, ŌĆ£Well, IŌĆÖm going to show you the church whether youŌĆÖre interested or not.ŌĆØ

She had told me that, in addition to the cypresses by their lake, her father had planted trees around their church. I had pictured a little border of trees around a church lawn. We turned from the back road onto a winding drive. This was no patch of lawn but a spacious green expanse, like an old-time camp meeting grounds. I am a lover of frontier American churches, and her parentsŌĆÖ Methodist church was one of them, in 1950s style. The modernist, almost cubist angles of the churchŌĆÖs walls and roof and entryway showed ingenious architecture combined with heartfelt pioneer-handyman carpentry. The trees she had known as saplings now stood in tall columns, with mote-filled shafts of late-afternoon sunlight slanting through the leaves.

We sat awhile with the engine off. ŌĆ£This is actually the second time IŌĆÖve been here today,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£I was here this morning. I come here every time IŌĆÖm in Dunedin. This was where the branch got stuck under the car.ŌĆØ

The church and grounds were like a place in a dream. The light through the leaves matched the sunlight that descends through coral reefsŌĆöthose celestial shafts that light up the bright reef fish swimming through. As Americans we have an attachment to the Good Place, the Peaceable Kingdom. Hope Spots might be the latest, trans-global, transoceanic expression of that vision. Once youŌĆÖve glimpsed such a place for even an instant, youŌĆÖll pursue it for the rest of your life.

Contributing editor Ian Frazier is the author of the forthcoming Hogs Wild: A Collection of Essays and Reporting.