The Last of the Wild and Man-Eating Tigers

In the Sundarbans region of India and Bangladesh, some of the world's last wild tigers roam free and ravenous. An expedition to film these elusive predators is tricky business. You may not see them, but they almost certainly are watching you.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Through the eyes of a tiger, the colors of the forest are muted, but its outlines are very, very sharp. Staring ahead, the tiger also sees far to the right and far to the left, due to exceptional peripheral vision. The tiger is crepuscular, meaning it hunts at twilight or in the twilit light before the dawn, and being a cat, its night vision is among the best in the animal kingdom, some six times better than man’s. So when rangers from India’s Forest Service led world-renowned big-cat biologist Alan Rabinowitz onto the beach of Kalash Island in the dark before the dawn, the tiger undoubtedly saw them.

Kalash sits on the southern fringe of the Sundarbans, the largest delta and belt of mangrove forest in the world. The Sundarbans is wrapped about the Bay of Bengal; one-third lies in India and two-thirds in Bangladesh. Although named for the indigenous sundari tree, the region is defined by water. Creeks and rivers fragment it into forested islands, and an aggressive estuary tide swamps and tugs at the land. The Sundarbans encompasses 3,860 square miles, an area somewhat larger than Puerto Rico. Half of the Indian side is densely inhabited and cultivated; the other half is the stringently protected , known locally as Tigerland.

In theory, the inhabited region and Tigerland are separated by the broad Matla River, which averages two to three miles wide. But the Bengal tiger is a powerful swimmer, and on Kalash beach, which faces Tigerland across the river, pugmarks are regularly found. So it was that early one dark morning, Alan and the rangers followed tiger tracks toward the forest. All was quiet. Dawn broke in steaming mist; a deer gave a bark of alarm, a monkey cried; the forest rangers stopped to listen; there was a roar—“a half roar” according to ranger Ashis Mondal, who has been working in this region for nine years—then brief tumult from the tree line and a whimper “as if the killing.” Then stillness.

“Those guards were nervous,” Alan says, “and I’m taking my cues from them. One turned to me and said, in all seriousness, ‘Can you climb trees?’ ”

Cofounder and CEO of New York City–based , the leading organization dedicated to saving big cats, Alan previously served for 30 years as executive director of science and exploration at the , and the two roles have led him to the world’s wildest places studying tigers, jaguars, leopards, clouded leopards, Sumatran rhinos, and bears. Early conservation efforts focused on throwing protective rings around endangered animals, resulting in small pocket populations surviving on islands of broken habitat—“megazoos,” Alan calls them. A pioneer in the establishment of genetic corridors to link populations, Alan has pulled off such achievements as the world’s first jaguar sanctuary, in Belize, and the largest tiger reserve, in Myanmar’s remote Hukaung Valley.

Speaking of his first work with tigers, in the Western Forest Complex of Thailand in 1987, Alan once described how Buddhist monks walked through the jungle at night, hoping to meet a tiger to test their belief that they didn’t fear death. It struck me that he had partly described himself.

“The combination of Buddhism and monks and gunfire—it was perfect for me,” Alan says. “I wanted adventure. I wanted wildness. I wanted to be alone. I wanted to accomplish something.”

Since then, Alan has tracked tigers throughout all their major landscapes, the diversity of which stands as a testament to the resilience of this remarkable species. Bengal tigers prowl heights above 13,000 feet in the Himalayan foothills of Bhutan and Nepal, as well as the forests of India and Bangladesh. The Siberian tiger strides the deep snows of the Russian Far East. Malayan, Indochinese, and Sumatran subspecies still survive, just, in the tropical jungles of southeast Asia. Two other subspecies, the Caspian and Javan, became extinct in the 1970s, the end of at least a two-million-year evolutionary journey. Before this trip, the semiaquatic Sundarbans was the only tiger landscape Alan had never seen.

[quote]Drastic loss of habitat, halfhearted efforts by governments, and an illegal market for tiger parts in China have reduced the number of wild tigers to 3,200—at a high estimate. “That's a far cry from the 100,000 that roamed a hundred years ago,” Rabinowitz says.[/quote]

“It’s a race against time trying to figure out how to save these tigers,” Alan says, and it is not clear whether he is talking about the rate at which tigers are disappearing or his own diminishing timeline. At 60, he projects an air of indomitable energy; his eyes, by a trick of their electric blueness, have striking intensity, giving him an expression of keen focus. Stocky and muscular, he exercises religiously, even on our four-week trip, working out daily in smothering heat in the makeshift gym of our home base, the 180-foot motor vessel Paramhamsa. But in 2002, Alan was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a cancer of the blood that has no cure. Inexorably, if slowly, it progresses. He has now, as he puts it with characteristic bluntness, “begun the process of dying.”

Alan’s mission on this trip is to determine whether Panthera should establish a program in the two-thirds of the Sundarbans that lies in Bangladesh, where very little scientific study has been done. His research begins in India, where the Sundarbans forest has been protected since 1973, when the government established , a nationwide conservation plan that now manages 43 reserves throughout the country.

It is March 2013. Our days will be hot, long, muddy, and not without danger, plying channels in small boats in a landscape of crocodiles, snakes, bandits, and, of course, tigers.

“You will not see a tiger,” Alan tells us matter-of-factly. “I have absolutely no expectation of seeing a tiger on this trip.” In 25 years of dedicated conservation, Alan has seen fewer than ten in the wild. “Visible tigers are usually dead tigers,” he says, “so the tiger has evolved with human hunting pressures to not be seen very easily.”

Nonetheless, in the Sundarbans, in this flooded forest, the tiger’s presence, unseen or not, presses close. It is manifest in the many pugmarks emerging from dark water, in the stories villagers tell of death by tigers and testimonials of survival, in the elaborate protective fences that surround each ranger station like a maximum-security prison, and in close encounters like that at Kalash beach. Here, evidence of the tiger is strewn with the casual arrogance of the truly mighty. There are many tiger habitats in Asia, but this is tiger territory.

The world has been trying to save tigers since the 1970s, when it was discovered that populations had shrunk precipitously, and in some places vanished, throughout Asia, home to all the wild tigers left on earth. But conservation has largely failed. Drastic loss of habitat, halfhearted efforts by the governments of many of the 13 tiger-range countries, uncoordinated objectives of competing NGOs, and, above all else, an unstanchable and illegal market for tiger parts in China have reduced the number of wild tigers to 3,200—at a high estimate. “Existing habitat right now could accommodate 20,000 tigers,” Alan says. “That’s a far cry from the 100,000 that roamed a hundred years ago, but I’d be happy if we got to 10,000 in large, stable, interconnected landscapes.”

In the Indian Sundarbans, a recent census posits around 103 tigers—these days a significant population. Estimates for the Bangladesh side run upwards of 400 but are based on shaky data. If the real number is even a fourth of this, the combined Indian-Bangladeshi Sundarbans tiger population would be one of the most robust left on earth.

All travel within the Sundarbans is by boat, and on the Indian side in particular there are very few places where it is feasible—or permitted—to set foot. Hence our generous mother ship, and hence, too, the flotilla of small craft tethered to her, like remoras leeched to a great white shark.

I am part of a 16-member team under the direction of filmmaker , who has made three prior lengthy research trips to this region and has worked six years to put this expedition together. We will chronicle Alan’s journey for a feature documentary that will draw attention to the tiger’s plight. I have been to this region once before and will be acting as the writer and researcher for the film. George, 69, is a veteran filmmaker and photographer of such outlandish places as the Antarctic (for the documentary The Endurance), Santa Monica, California (for the book and movie Pumping Iron), and the planet Mars (for the Imax movie Roving Mars).

Our plan is to have camera teams out before dawn and dusk every day to catch the best light. George and his crew will follow Alan as he meets with local experts and villagers and gets to know the region.

At breakfast in the boat’s main cabin the first morning, Alan reports that he had a bad dream in the night that involved his parents, both of whom died years ago. His youth in Far Rockaway, Queens, had been rough and troubled, mangled by a devastating stutter. His teachers, he says, could not “understand that I was normal inside my head, I just couldn’t get the words out.” Like many stutterers, he found activities that allowed him to speak without stuttering. “One of them is singing,” Alan says, “because it keeps airflow going. And one of them, for me, was talking to animals.” In a closet in his house, he kept his small menagerie of allies: a green turtle, a chameleon, a hamster, a garter snake. “I like tight, dark areas, and I’d go into the closet and we would talk.” This love of animals eventually led to his study of biology and zoology, first at Western Maryland College and then at the University of Tennessee.

But life before college was mostly dedicated to channeling aggression into a series of highly physical activities. He ran with gangs. He got in fights. He lifted weights and wrestled. His relationship with his father was particularly fraught and at times violent. The turning point came in 1970, when Alan was 17. “He came up into my face, and I grabbed him by his neck,” Alan says. “I said, ‘You are never—you are never to touch me again.’ ” One night, he stood over his father as he slept—a practice run, in case he ever chose to kill him. “I put my hands near his neck, just to see if I could do it,” Alan says.

Alan’s dream was like an omen. “I woke up afraid,” he says. As he left his cabin this morning, he learned that a local man had just been killed by a tiger while fishing nearby.

The aggressiveness of the Sundarbans tigers is notorious. Elsewhere, most attacks on humans are by tigers too old or too injured to hunt wild prey, like the recent killings reported in northern India. But the Sundarbans tiger seems to regard humans as easy, opportune prey, leading the region to be called one of the most dangerous places on earth. Decades ago, as many as 100 people were killed by tigers every year in the Sundarbans. Today that number has been reduced to around six, through such tactics as rapid-response ranger teams that remove straying tigers from villages and strenuous efforts to minimize human presence in Tigerland. The last time a tiger killed a person in an Indian village was in 2004; all the other victims were killed in the reserve, across the river.

“The Sundarbans tiger is tougher than many others throughout its range,” Alan says. In this primordial swampland, the tiger is hunted less, fears people less, and is consequently more aggressive. It is, as Alan says, “more similar to tigers of old, when people truly feared to walk the forest among these beasts.”

The local man recently killed was 72-year-old Kartic Dakua, from Jharkhali, a village we are motoring toward, about an hour upriver. Since he and his companions had been in the prohibited area, details were not forthcoming. Families of people killed while in the forest legally, with permits to fish or catch crabs or search for honey, receive government compensation. But families of those killed while trespassing in the tiger’s territory receive nothing, and consequently these deaths are often not reported.

The Dakua family’s small house, built in the local style of dried mud and thatched with dried grass, stands in the midst of green paddy fields and is reached by a brick path leading from the river jetty. Members of the extended family had gathered in the sun outside the house, including Dakua’s widow, a thin, fragile-looking woman, and his son, silver haired, with fine chiseled features pinched with grief. Incredibly, another of Dakua’s sons was killed by a tiger five years ago. Now, through a local interpreter, Alan introduces himself and addresses the son. “Are you angry?” he asks.

“Yes,” the son replies passionately. He is angry, the interpreter says, with the man who persuaded his father to fish illegally in the reserve. Sitting on a mat in the compound, Alan rephrases his question: he meant, pushing, are you angry with the tiger? The son speaks sadly in Bengali: “No. The tiger has his separate territory. We have our village. If a robber comes into my home, then I would kill him. My father and another man went into the forest; he was in the core area, and he was killed.”

The tiger is not only the largest cat in the world; it is also the third-largest land carnivore. “The only things bigger walking the earth, in terms of carnivores, are the polar bear and the brown bear,” Alan notes. The tiger is built for power and stealth, not speed. That said, tigers have been clocked at 40 to 45 miles per hour, although only over very short distances. Killing small prey, such as chital deer, the tiger uses its own body mass, flattening the animal and crushing its skull. Most tigers weigh 300 to 500 pounds but can bring down a bull of more than 2,000 pounds.

“The tiger has huge canines,” Alan says. “They can go to three inches in length. But more than just being long, they’re robust. They’re built to take incredible forces, so that when they sink their teeth into the neck of their prey, and then snap that neck, they don’t break their canines.”

[quote]The aggressiveness of the Sundarbans tigers is notorious. Elsewhere, most attacks on humans are by tigers too old to hunt. But the Sundarbans tiger seems to regard humans as easy, opportune prey, leading the region to be called one of the most dangerous places on earth.[/quote]

In the Sundarbans, a man will bare a leg or an arm or pull up his shirt to show scars from a tiger attack. Others, like a local wood gatherer, watched a tiger carry his friend by the neck, “like a mouse,” into the forest. Traditional wisdom holds that there is safety in numbers. But Colonel Shakti Banerjee, the majordomo of our expedition boat, tells a different story. Banerjee, 62, retired from his military career in 1998 to work for the World Wide Fund for Nature of India and serves as a kind of liaison officer for our team. In 2003, he says, eight honey gatherers “got a bit greedy” and went illegally into the highly restricted core area of the reserve. “A tiger came and took the ear of one man, it killed three men, and carried one away.” In 2002, Banerjee had been sitting on a village embankment on nearby Bali Island, enjoying the afternoon air, when a tiger came ashore and swaggered into town. It made a warning swipe at a woman in its path, scratching her, and she fell down in shock. “She became speechless,” he says.

The ability to strike a human dumb with sheer, cold terror is a power very few mortal beings possess. She was struck to the ground, dumb—the language belongs to the realms of religion and magic, and it is on such powers that the people of the Sundarbans rely. In both the predominantly Hindu Sundarbans of India and the predominantly Muslim Sundarbans of Bangladesh, the tiger is worshipped, and along the riverside stand small shrines to the benevolent forest goddess Bonbibi and her tiger consort, where offerings for protection, such as flowers and sweets, are regularly presented. With its cult sites and offerings, the tiger is like Pan, the ancient god of forests and of wild, lonely places, whose name is the origin of panic, that sudden terror that grips a man who has strayed a little too far from his forest path, delayed a little too long in the crepuscular shadows of evening.

Alan tells a story about how, while tracking a tiger in Thailand, he circled back and found himself face-to-face with the animal, which, it turned out, had been tracking him: “I thought, If I make myself small the tiger will go away. So I sat down. I was scared. I started to get up and I thought, Now the tiger is going to kill me. But the tiger growled and walked away. People may say ‘I got away from the tiger,’ but no one gets away from a tiger; it’s the tiger that lets you go.”

We are moving east toward the India-Bangladesh border. The scenery is wilder, the trees taller, interspersed with great quills of palm fronds. The tide that twice daily floods the Sundarbans also loosens and deposits sediment, continually reshaping the waterways. The captain of our boat, Tapan Ghosh, a 49-year-old Bengali, has been plying these waters for 15 years, working oil barges from Calcutta to Assam as well as tourist vessels. He navigates without charts, knowing that no surveyor can keep abreast of the shifting configuration of the river.

A favorite saying in the Sundarbans is that without the tiger, there would be no forest—meaning the forest would be plucked bare if fear of the tiger did not keep people out. But the rugged Sundarbans forest also protects the tiger. The long, chaotic roots of mangrove trees twist and coil like snarls of barbed wire at the water’s edge, and boot-grabbing mud around the trees is spiked with mangrove pneumatophores—spitefully pointed, upright breathing roots that cut and impale. Cobras, king cobras, kraits, and vipers live in the ooze, as do crocodiles, and one day, beside our boat, the black triangle of a shark fin cuts the water. The Sundarbans, according to Alan, “is one of the nastiest kinds of habitats to try to traverse of any existing in the world. The ability of the tiger to not only live, but to clearly thrive in the Sundarbans, to be surviving on brackish water, to navigate these mangrove swamps and mud, shows how unbelievably resilient the tiger is. The tiger will do anything to survive.”

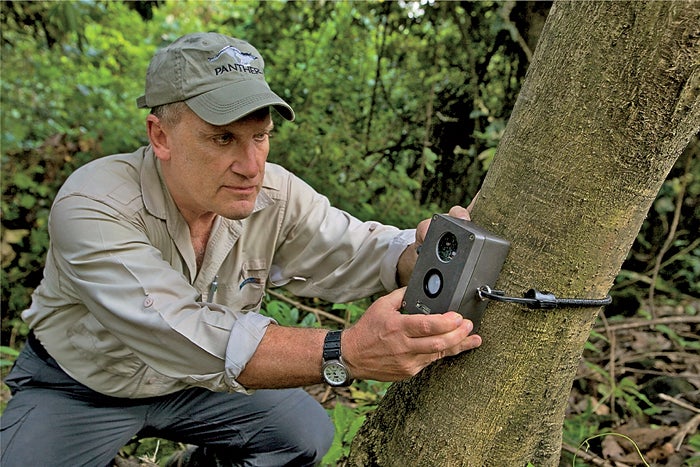

Camera traps used in the first scientific tiger census of the Sundarbans, conducted by the World Wide Fund for Nature of India in 2011, gave the most reliable estimate of the number of tigers here and also yielded thrilling images of the hidden forest. In their secret places, tigers nonchalantly tread the forbidding mangrove spikes with big, fat paws as they amble on their mostly solitary way through the shadows. One tiger passes so slowly across the camera frame that the effect is of a professional pan across the black, flame-like markings on its amber body.

In the afternoon, our boat arrives at Burir Dabri, the last ranger station in India. A watchtower looks out over the forest and toward the Raimangal River, across which is Bangladesh, one to two miles away—a distance the Sundarbans tiger has no difficulty swimming. Surveying the scene from behind his aviator glasses, deputy ranger Shantanu Kulari, who oversees this station, estimates that during his four-year posting he has seen tigers some 50 to 60 times. On a casual walk, looking through the wire fence enclosing the station, I see three sets of tiger tracks, two male and one female.

Kulari has also seen armed poachers from Bangladesh, including a gang that, just three days before our visit, engaged his rangers in a gun battle, resulting in the death of a poacher and the grave wounding of two of his men. “They have been coming for deer for years,” Kulari says. “But now they come to create a panic. They come well armed in groups of six to eight. But so far they have made no incursion.” As Alan notes, “There’s lots of easier places to go and hunt.” Still, the view across the border makes plain that the protective nature of this habitat will be tested. Behind us lies the closely monitored Sundarbans of India, and ahead, where the tigers are drifting, the vastly larger, mostly unknown Sundarbans of Bangladesh.

Three hours of motoring brings us to the Indian border. After crossing, we glide along rivers and through channels toward the official border of Bangladesh. We will be the first noncommercial vessel to legally make this crossing, the beneficiaries of a new border treaty between the two countries, which will also facilitate joint scientific and law-enforcement ventures in the Sundarbans.

By late afternoon, we are anchored in the port of Sheikhberia, Bangladesh. Clearly, we are in another land. Behind our boat is forest, but facing it, across the gunmetal water, a line of dusty buildings roofed in sheet metal or slumping thatch stand on bare, baked soil. The few isolated palm trees highlight the lack of other vegetation rather than evoke any illusion of shade. Human settlement has stripped bare what was forest. Waking to this landscape, you would think you were somewhere in the desert, maybe on the Nile.

For two days, we wait for our entry permits to clear. At last the boat engines grind, and we slowly build lumbering speed toward the shadowed water of the forest. There is notably more traffic of small fishing boats and skiffs. We see them nosing out of creeks and channels, often foundering under the weight of cut wood or branches of palms.

The Bangladesh Sundarbans covers 2,316 square miles, twice the area of India’s, yet has significantly fewer management resources. With rangers at its four stations lacking even gasoline for basic patrols, the forest is not only unmonitored but largely unknown. “There’s very little science going on in the Bangladesh Sundarbans,” Alan says. Utterly unconfirmed, for example, is the number of tigers. Almost all sources confidently cite at least 400, but this figure was extrapolated in 2009 from the movements of two radio-collared tigers that later died, possibly as a result of the collaring.

In the evening, one of the few people able to shed light on this region comes aboard to meet Alan. Petite, bearing an air of quiet confidence, Samia Saif is a 28-year-old Bangladeshi and a doctoral candidate in anthropology and conservation at England’s University of Kent. For 11 months beginning in 2011, she traveled with a locally recruited field team through the Sundarbans, interviewing villagers and poachers—dangerous work for which she was threatened with rape. Samia’s research documented the presence of professional tiger poachers, as well as considerable poaching of tiger prey, such as deer. But she did not find—yet—any international organized poaching rings with links to China, which have wiped out tigers elsewhere in Asia, including parts of India.

���ϳԹ��� on the deck, Samia and Alan study a map of the area. From the black night river comes indistinct noises—lapping water, insects, distant outboard engines. “No one knows what’s going on here,” Samia says, pointing to the forested area on the map. The dearth of information extends to prey populations, the forest’s health, and human incursions for fish, deer, or wood, as well as basic facts about tigers. More is known about tigers straying outside the forest, and a , compiled by the country’s forest department, estimates that marginally more tigers are lost each year to revenge killings by villagers than to poaching.

On our boat, we have all seen a video of such a killing. Taken a year ago and played on Al Jazeera, it shows a village mob killing a tiger not far from where we are now. The tiger is cornered in a hut, hung from a rope, hacked with an ax, and dragged through the mud while men celebrate with riotous cheers and laughter. Samia has been told of the aftermath of such killings, the dark reverse of the worshipful view that tigers, even dead, have supernatural powers. “Village women descend on the dead tiger in a mob with knives to cut off pieces,” she tells Alan, who listens riveted. “There are too many for forest officers to hold off. They take the teeth, claws, whiskers, bones, genitalia, for amulets or to eat. They will take a small piece of bone and put it in a banana to eat. They kill in a mob, all together, so no one knows who does this.”

One of Alan’s ongoing projects is assessing local opinions of tigers. “I ask people at every single level if they would rather just see this animal gone from the face of the earth,” Alan says. “Because if that’s truly what they want, then perhaps I don’t want to invest my time and effort in that place, fighting a very upstream battle.” To address this question head-on, Alan wants to take the video to a nearby village that recently killed another stray tiger.

The next day, Alan, accompanied by Samia, is standing with his laptop before a rustic mosque in a small village an hour’s travel upriver. A group of elders, striking men with long white beards and wearing knitted skullcaps, greet him. Women in bright tunics and long dresses, many with their heads veiled, along with giggling children and younger men, stream into the village green from the path along the river. With the crowd growing, a robust-looking man in his thirties, his arm in a sling, volunteers the story of this village’s tiger killing, which took place four months ago. As Samia translates, he describes how the tiger had been coming to the village over several months, and then early one morning, as he went to get his fishing nets, it attacked him—he pointed to his arm. Friends rushing to help with knives and weapons killed the tiger; he could not give further details “because I was senseless for three days.”

“I want to show you something,” says Alan, opening his computer. “Get close. I want you to watch and tell me what you feel when you see this.” Gathered around Alan, the villagers watch the film, mostly in silence. One young man laughs, some smile, but most faces are solemn. “So,” Alan says when it’s over, “what do you think?”

“It makes me happy,” one of the women volunteers, speaking through Samia. Alan laughs, darkly. “Do you think there is a way for tigers and people to live together?” A man speaks in a ringing voice from the orderly crowd: “They want the tiger to live in the forest, because without the tiger there would be no forest; but they don’t want it in the village.” Other voices now tumble upon one another. “The tiger is here because there is no food, because the poachers are killing deer in the forest and poisoning fish.” “We would like stronger teams to come when there are tigers.” “The government should make some tiger teams that have power to arrest the poachers.”

Back on board our boat, Alan is visibly energized. The reasonableness of the people’s observations and requests impressed him. The measures they asked for could be supplied. Wading into a village of tiger killers in this so-called heart of darkness, he has found voices that match his own.

Alan's health has been the object of catlike scrutiny throughout our trip. The heat has been intense, the hours long and inconvenient, and the mode of travel—mostly confined to the river—frustrating. Still, his energy, that barometer of strength and health, has not faltered. Watching the dailies in our small screening area, director George Butler remarks with satisfaction: “None of these nature films about penguins or elephants have what we have. We have the tiger, Alan.”

Several things have convinced Alan that the Bangladesh Sundarbans is worth Panthera’s investment. The lack of resources—for patrol boats, gasoline, supplies, ranger uniforms, even drinking water—is all too visible. But, as Alan notes, “I also see, when talking with the guards and forestry officials, a desire that they get better training. The government clearly values this area. They have valued it just by making sure it still exists in this country.”

Panthera’s first step would be to work with the Bangladesh Forest Department and also the Wildlife Trust of Bangladesh, the single outside conservation agency on the Bangladeshi side, to get good baseline data on tigers and prey and start the kind of rigorous monitoring and patrolling that captures and deters poachers. “We’ve developed special camera traps; we have all the technology,” Alan says. “We can do it. We just have to have it done by a group of young, passionate, intelligent people in a systematic way, brought together under one umbrella.”

Faint rain is falling as we divert from the main river into a greenish-brown channel. Around a bend, we are joined by an enormous, showy egret that conducts us, with much pomposity, upriver. “When you remove from nature an element like the tiger that evokes fear, caution, mystery—when that’s gone, then everything that made humans the dominant species on this earth is also taken away,” Alan says. “Things that shaped our human behavior help make us stronger—help make us tougher.”

Saving tigers, as Alan repeatedly advocates, “is not rocket science.” Tigers are not finicky about habitat or diet. They breed well. They are resourceful. With science-based management, they could double their current population in 15 to 20 years. They are, as the Sundarbans shows, extraordinarily adaptable. “These tigers are doing what they have to, despite adversity, to survive,” Alan says. “They’re not lying down and dying. That behavior—whatever it is that might be manifested down the genome of this species because of this—needs to be saved.”

We can buy time for the tigers; we can even buy their survival. But Alan’s leukemia timeline is nonnegotiable, if still unknown. “There’s a lot of times,” he says, “especially as the leukemia progresses, and as I get older and I feel more tired, that I think, Ahh, why not just lie back a little?” His stutter is not entirely vanquished and in moments of emotion is felt as a kind of flutter, like the rapid wingbeat of a bird. The wings are beating now. “I think about that, and I get really angry at myself, thinking, My struggle is not nearly theirs. If they can struggle to the last, so can I.”