Seeking the Lost Art of Growing Old with Intention

In a world where our time and attention are fractured into smaller and smaller bits, legendary biologist and runner Bernd Heinrich is a throwback, a man who has carved a deep groove in his patch of Maine woods

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Great lives often begin amid tumult and suffering. Seventy years ago, long before Bernd Heinrich became one of history’s , and ages before his scientific studies on ravens made him a , he was a skinny, impoverished kid living in a hut in the forest of Hahnheide, in Germany. Before World War II, his family had owned a vast agricultural estate roughly 400 miles east of there, in Poland, with foxes and storks and rolling fields of potatoes and sugar beets; but after the Eastern Front pushed west, they became refugees. Bernd’s father shoveled manure to survive, and the family lived mostly off forage—nuts, berries, mushrooms, and also trout, which Bernd caught with his bare hands.

It was a confusing time. Bernd and his sister had no other playmates, and he spent long days exploring the forest on his own. His father, a top entomologist specializing in wasps, was marginalized in postwar Germany, and he could be tyrannical. Once when Bernd was five years old and collecting beetles, he found a prized rare specimen at the base of a stump, and his father confiscated the insect to punish him for being “overstimulated,” as he put it, when the boy leaped for the bug. Real men, Gerd Heinrich believed, were unflappable, with nerves of steel.

Was it there in the Hahnheide that Bernd formed the spine to notch an American record for the 100 kilometers, running the distance at a 6:25-mile pace in a Chicago race in 1981? Did hardship form the writer whose classics and offer readers both impassioned tales about animals and meticulous science?

No, a later, happier chapter made him who he is.

In 1951, when Bernd was 11, his family wrangled passage to the U.S. and landed in western Maine. They planned to grow potatoes. Instead they were taken in for a summer by a kind family, the Adamses, whose ramshackle farm was a mess, a melange of dogs and cows and chickens and broken tractor equipment. To Bernd, the place was paradise, as he writes in his 2007 memoir, , recalling the adventures he shared with the two eldest Adams kids, Jimmy and Billy. The boys built a raft out of barn wood and spent countless hours watching baby catfish and white-bellied dragonflies. The Adamses taught Bernd English. He killed a hummingbird with his slingshot. He ran around barefoot and shirtless.��

Bernd Heinrich is now 77 years old and the author of 21 books. The vaunted biologist E. O. Wilson speaks of him as an equal, calling him “one of the most original and productive people I know” and “one of the best natural-history writers we have.” Runners also revere him, for his speed and for his 2002 book, . “He was the first person of scientific stature to say that ultramarathoning is a natural pursuit for humans,” says Christopher McDougall, author of the 2009 bestseller . “He did the research himself, in 100-plus-mile races.”

But let’s set aside the literary plumage for a moment. In many ways, Bernd remains the same inquisitive kid who found bliss in his first American summer. He still runs, though no farther than about 12 miles at a time. He still watches wildlife, intently, and he still climbs trees. Sometimes he even climbs trees in snowshoes. In old age, he is embracing the joys of youth anew.��

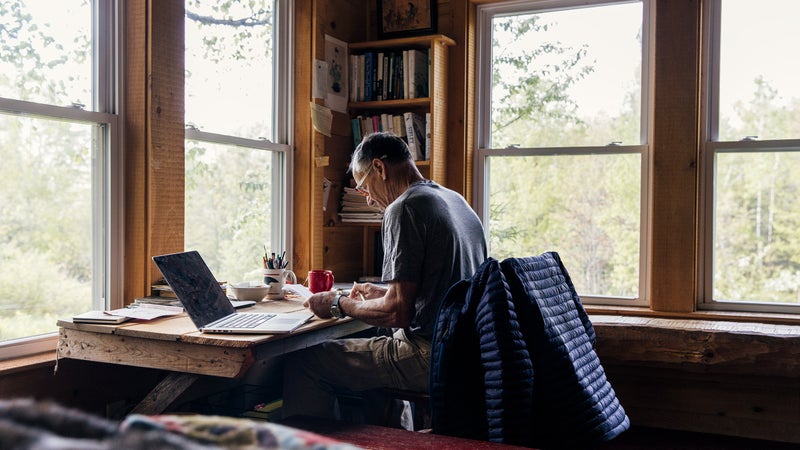

And he has returned to the Maine woods, to a 640-acre plot about 15 miles from that old farmhouse where he spent the summer of 1951. He owns a pickup truck and drives without compunction, but he does not have running water, phone service, or a refrigerator. He heats solely with wood and relies on a small solar panel to power his laptop and Wi-Fi router. He sometimes goes two months without ever leaving the property.��

Bernd is hardly a hermit. For the past three years, he has shared the homestead with his partner, 57-year-old Lynn Jennings, a nine-time U.S. cross-country champion and the 10,000-meter bronze medalist at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. It’s a happy and fruitful arrangement. Over the past five years, Bernd has staged a late-life creative tear that calls to mind Johnny Cash or Georgia O’Keeffe, churning out a steady stream of academic papers, columns for , and four books, including , a just-published guide cowritten with Nathaniel Wheelwright, as well as 2016’s , which renders certain jays and blackbirds on his property as unique individuals, as fully realized as Elaine and Kramer on Seinfeld.��

When I began adding up Bernd’s septuagenarian streak, I realized that here was a rare man—a throwback. We live in an age that affords little time and space for communing with nature. We’re busy. Our days are fragmented. But Bernd has dug in his heels against this collective drift. He has recognized where he wants to be in old age and settled in, with purpose.��

In recent years, my life has echoed Bernd Heinrich’s to a degree. I, too, have reconnected with my own private Eden. In the autumn of 2014, after my only child left the nest, I moved from Portland, Oregon, to the countryside of New Hampshire with dreams of roughing it. I would heat with wood. I would spend winters without running water. The idea was to reinvent a rambling, 1790s-built summer home that has been in my family since 1905. My grandmother swam in the nearby lake as a child. I caught fireflies on the lawn when I was five. My new life there would be just like Walden, except with Wi-Fi.��

One of my first moves came that fall when, for $400, I bought a used woodstove and hired two musclebound guys to hoist the squat, 300-pound iron box up over the door lip, around a corner, and into place beneath an ancient brick chimney. The air was warm that evening, but there was a gentle breeze and a dry rustling in the trees, and I shivered with the prospect that I would soon be ensconced in the cold, wintry brilliance of my adventure.��

The vaunted biologist E. O. Wilson speaks of him as an equal, calling him “one of the most original and productive people I know.”

I was also anxious, for I harbored a secret so humbling that I was afraid to share it with anyone: I had never actually operated a woodstove. I’d seen other people build fires in stoves, but I had always watched from a distance, enviously, feeling helpless and pathetically urban. At 50, I was still a fire-building virgin, and now my survival hinged on a skill I lacked.��

That September, I watched numerous instructional videos on YouTube. Then I lit my first fire. The flames danced behind the glass of the firebox. The room filled, slowly and subtly, with a warmth that seeped into my bones, and the joy that I felt was primal: a campfire is home, especially when it warms a house like the one I was living in. The place has six bedrooms, an attached barn that has been gently tilting into the earth for over a century, and a scruffy 1.2-acre lawn denuded of trees. Not a single wall was insulated, so I had to shut down the plumbing and use the privy in the barn, lest the pipes burst.

Still, that first winter was grand. I holed up in a single sealed-off room, sustained by the fire. I chipped crusted snow to boil for dishwater and cross-country-skied every afternoon. I carried armloads of firewood in from the barn and wandered the cold house in old sweaters flecked with bark, a ragamuffin lord presiding over a new, untapped universe. No one had wintered there for nearly 80 years.��

But I wouldn’t say I was living in that house, exactly. The place was still owned by my mother, who was 84 and afflicted with Parkinson’s. I was just camping there, fecklessly, experimentally. I’d never once used a chainsaw. The names of the animals ranging across the lawn remained a mystery to me. In order to ground myself, as I craved, I needed to go deeper. I needed to learn things—about living on the land and about aging with grace.��

I had this vague notion that what I needed was a mentor, and I’d heard about Bernd. I’d read his book on running, and I’d seen a recent photo of him scything his own grass, shirtless, his senior-citizen sinews reminiscent of a Greek statue. In time, feeling slightly cowed, I wrote him an obsequious note. Generously, he invited me up to his cabin for a visit.��

Bernd lives three hours northeast of me, half a mile off a country road and up a hill on a path that in winter can be negotiated only on snowshoes. He returned to western Maine in 1977, after earning his Ph.D. in zoology at the University of California at Los Angeles and starting a job teaching at UC Berkeley. He bought a sliver of forest appointed with a battered shack that he lived in very part-time. He soon built a rough log cabin, felling the trees himself. He often stayed there four days a week, commuting east from the University of Vermont, where he began teaching biology in 1981. But after retiring in 2004, he and a stonemason friend reorganized a jumble of stones, the remnant of a vanished cabin’s foundation, into the base for Bernd’s new home.��

I start climbing toward that home late on a winter afternoon, when the conifers are laced with new-fallen snow. I follow the path until it levels out, then I hook left and find myself in a clearing that contains, magically, all the sights I’ve read about in Bernd’s books. Here is his older cabin, a muted brownish silver, at the edge of the woods. Here is the gleaming new cabin and, on one wall, the doughnut-size hole that a northern flicker, a star character in One Wild Bird at a Time, carved into it. Woodsmoke billows out of the chimney.��

Bernd and Lynn step out onto the porch to greet me, each cradling a mason jar filled with beer.

“You made it!” says Bernd. “You’re here!” says Lynn. There’s a specialness about arriving that would be absent had I simply stepped in from a parking lot.

Inside, the house is immaculate and sparsely appointed. The pine floors are lustrous, the books on the shelves upright, the interior woodpile absent of dust. A wooden chest that Bernd made in the eighth grade sits in the living room, and upstairs there’s a battered thermometer screwed to an exposed beam. The clutter is so minimal that each little item seems almost holy: this ladder leading upstairs, this knotted rope hanging beside it.��

In the fading light, Bernd is somehow of a piece with this unassuming decor. He is a humble man, withdrawn and shy, with a five-foot-eight frame and wispy white hair. I’d come expecting a crisp German accent, but no, he speaks with the down-home inflections of Maine, saying “remembah” for remember and invoking “wicked” as an all-purpose adjective. There is nothing hifalutin about him.

But he exudes a quiet force, and he moves directly to the topics that matter. Within five minutes of my arrival, Bernd assures me that he will be buried on the property. “My afterlife will be here,” he says. “My body will be here, in the trees, in the birds, in all living things.”

He talks about the joys of hunting deer on his own property. “Anywhere else,” he says, “it’s just shooting.”

He speaks with disdain for people who are overly pious in their regard for nature—who, for instance, are against wood-burning stoves or think that bird feeders are bad because they build up dependence. “I hate people who want to put a fence around nature,” he says. “How can you be a part of nature if you don’t interact with it?”

We drink and we eat, and in time Lynn throws open the door so the night cold sweeps in. Then she steps to the coolest corner of the cabin, the closest thing they have to a refrigerator, and scoops a squirrel carcass up off the floor. She flings it outside, onto the snow.��

“Come here, owl!” she cries.

“Come here, owl!” Bernd cries. They cast their voices skyward, up toward a tree, where a barred owl is perched on a limb. This owl is an old friend of Bernd’s. On many other evenings, it has swooped down to the snow, almost to the doorstep, to retrieve a tossed chunk of squirrel.��

“Come here, owl!”

“Come here, owl!”

The owl levers its head slightly, watchful, but it does not heed commands. We are in a wild place.

The next morning, Bernd and I strap on snowshoes and go for a run. It’s an unnerving enterprise. Long ago I was a decent runner, but I’m now a skier and cyclist. Before driving north, I’d read a 2015 article that described Bernd, then 75, finishing off a workout at a 6:05-mile pace. He can still run a 10K in about 47 minutes, and I’m worried: Is this old man going to smoke me?

He could, possibly, but he’s merciful. He starts out at a gentle 12-minute-mile crawl, glancing back at me every so often, solicitously. “Is everything OK?”

Everything is OK. The packed snow has a fresh dusting on top, and we dip and climb through thick woods until we’re standing on Hemp Hill, where long ago Bernd discovered a flourishing marijuana crop, cultivated by an unknown entrepreneur. I think of him hunkering down in the nearby blind, researching , his 1989 landmark work, and its 1999 follow-up, . He studied both wild ravens and birds he hand-raised from nestlings and kept in a huge 40,000-square-foot aviary before releasing them. Ravens can live more than 50 years in captivity, and over time Bernd apprehended a Shakespearean intricacy in their social lives.��He noted the obeisance that lesser males displayed around Goliath, the alpha. And observing ravens calling loudly near a moose carcass, he wondered if they were being altruistic in summoning their friends to a feast. To find out, he hid in a blind made of balsam fir and spruce branches, playing recorded calls on a loudspeaker, and spent countless dawns watching ravens from the top of a tall spruce tree. Bernd went on to famously demonstrate that the calling ravens were actually motivated by self-interest. They were rootless juveniles, it turned out, who had discovered food in a mature raven's territory. By inviting other ravens to feed, they avoided being chased off themselves.��

As we run, he tells me that in 2014, Goliath and his mate, Whitefeather, found themselves in conflict with a third. “For a couple days,” he says, “I saw huge aerial displays involving three ravens”—the pair, most likely, and an interloper. “I’d see two birds displaying their feathers at once. I’d see one bird chasing another, trying to get rid of it.” It was a love triangle, probably, but however it resolved, Bernd has not seen the pair since 2014, and he’s left only with questions: “How long do ravens stay together? What about jealousy?” Even now, Bernd finds himself scanning the woods in vain.��

We pass a river crusted in ice and stand on the shore as Bernd explains how, each summer, he and Lynn clear rocks from their chest-deep swimming hole. At one point, Bernd says, “That’s where Lynn shot her first deer.”

“I know the landscape,” he tells me, “and so I notice when something’s out of place—when the grass is bent, say. I didn’t know what I was going to research when I started living here full-time. But now I’m open to whatever comes along. It’s like being a kid again; I just go to nature and find the question.”

A few years ago, Bernd saw some ruffed grouse diving under the snow. He started watching them and established, finally, that they did it not to sleep but rather to hide out in daylight from predators. He might have submitted his observations to Nature or Science, but instead he sent it, as he has sent 11 consecutive scientific papers since 2013, to , a journal that 56 years ago, when it was known as Maine Field Naturalist, published an article that later embarrassed Bernd.��

“Weasels in Farmington” was Bernd’s first published paper, and it was little more than a medley of simple, clipped sentences. “Rabbits were plentiful during both seasons,” it reads, “and ruffed grouse seemingly scarce.” When Bernd was in his thirties, teaching at Berkeley, he expunged the paper from his curriculum vitae and eschewed the title of naturalist, choosing instead a label that implied more scientific rigor: biochemical biologist. He was bowing to public opinion, he says, which held that “being a naturalist was being a sissy.”

But over time, he says, he grew uneasy with the esoteric quality of the papers he read in scientific journals. He became so nostalgic for the simplicity of “Weasels in Farmington” that last year he gave a speech bearing the title. Meanwhile he resolved that going forward, he would only make observations from nature. “Popular thinking,” he says, “holds that naturalists are not critical thinkers. They can’t do ‘hard science.’ But a naturalist is someone who is a keen observer, and to do something original and true, you have to be an observer first. I consider myself a biologist, but I became one by being a naturalist first.”

For me, what stands out about these papers is the curiosity Bernd brings to familiar turf. Nearly all of us spend our days as he does, plying the same paths, and for millennia—right into my grandparents’ earliest days—we were obliged to notice subtle shifts in our local landscape, to ask whether it was time to bring in the wood or to harvest the acorns. Now our senses are dulled, our eyes fixed on the screen. Do we ever notice the natural world?

As Bernd and I run, we watch for wildlife. Beneath some old apple trees we find the tracks of wild turkeys that have been picking at rotten fruit in the snow. Nearby are the tracks of three coyotes, one of which appears skittish: its marks come right up to recent human footprints, then dart away. Bernd had observed this behavior, possibly this coyote, before. Now he bends to the snow to investigate.

Anyone can look at coyote tracks, of course. But when I see Bernd do it, I’m aware of a larger story—of a man who experienced the trauma of war as a child, then learned that peace lies in nature and decided to make his life about connecting to it and understanding it.��

But Bernd’s wartime experience exerts a natural force of its own; the pain lingers in his animal brain. In 2016, he traveled with Lynn back to the Hahnheide forest. He went to search for memories, for places that figured in his family’s exile, and he located the exact spot where, seven decades earlier, he’d captured a rare wasp that he was able to trade back to his father for the beetle that was taken away.��

“I saw that,” he says. “I saw that and…” Now his head crumples into his hands, and he begins sobbing in a mix of anguish and joy. “I thought, Look at how fortunate I am and look at what I came from: nothing. We could have been stuck behind the Iron Curtain forever.”

Soon, in discussing a recent trip to New York City and the endless gray expanse of buildings he passed on the outskirts, Bernd surprises me with another spasm of weeping—a flashback to a wartime horror. “All I could think about,” he says, “was going through Hamburg with Papa. The city was rubble as far as the eye could see.”

He talks about his life not as calcified fact but as a mystery he’s still trying to make sense of, right now, as he’s speaking. “I don’t know how I happened to come back to this land,” he tells me. “It was brewing in my subconscious for a long time. I always wanted a cabin, and I guess I was doing things in an unconscious way that were bringing me here.” It was only after he’d begun construction that he found, through research, that long ago Jimmy Adams’s father, Floyd, had lived in the house whose stones form the base of his new cabin.��

“We all want to be associated with something greater and more beautiful than ourselves, and nature is the ultimate. I just think it is the one thing we can all agree on.”

As Bernd and I speak, Lynn is in the kitchen, washing the dishes. During her pro career, she was a warrior in the scrum of middle-distance contests, a fighter known for her merciless kick. Her brio has not dwindled. These days she’s a competitive rower. She can ride her bike 100 miles in just over five hours, and she still runs a bit, sometimes with Bernd, with whom she enjoys a playful rivalry.��

She applies most of her energy to homesteading, though. She rhapsodizes about the “moments of exertion” that come with dragging an 80-pound sled filled with groceries up the hill. To get the old newspapers they use to start fires, she dives headlong into the recycling bin at the local dump, invoking, she quips, a “Fosbury Flop combined with a half gainer.”

Cabin living has been a lifelong dream for Lynn. In 1978, when Runner’s World ran a story celebrating her early prowess, she said, “You know what I’d like to do someday? I’d like to homestead. It would be great. Build your own house, forget about telephones and television…”

“I remember reading that article,” Bernd tells me. “I thought, ‘That’s the girl for me.’ ”

For a split second Lynn glowers at him, scandalized. “Bernd!” she says. “I was 18 and you were—what? Thirty-eight?”

Bernd shrugs, smirking slightly. But he says nothing, and I reckon he’s savoring the fact that eventually he did meet his dream girl, in 2011, when Lynn invited him to speak to her running camp in Vermont. At that point he was single, in the wake of a divorce. (He’s been married three times and has four grown children.) He invited her to visit the cabin.��

“I got a quarter of the way up the hill,” Lynn remembers, “and I knew this was where I was supposed to be.”

Bernd writes about Lynn in One Wild Bird at a Time. As the couple sat around a winter bonfire at night, sipping red wine, he noticed that his beloved barred owl had shown up by surprise, and he regarded its arrival, equally appreciated by Lynn, as the most wonderful thing he could hope for. “In the moment of joy and mystery,” he wrote, “I felt connected with all the moments of my past and now my prospects for the future.”

A special place can contain all stories—all of the past and all of the future, all the beginnings and endings. In 2016, the summer before my mom died, I drove her up to New Hampshire for a final visit. By then she was heavily medicated, but when we crested the final hilltop, with its stunning view of the local pond, her eyes glimmered with delight.

Her reaction was rooted in long memory, and also in nature. She was a naturalist. So many of us are, in our way, and as Bernd sees it, this is a fine thing. Indeed, it could save us. “A naturalist,” he e-mailed me, “is one who still has the habit of trying to see the connections of how the world works. She does not go by say-so, by faith, or by theory. So we don’t get lost in harebrained dreams or computer programs taken for reality. We all want to be associated with something greater and more beautiful than ourselves, and nature is the ultimate. I just think it is the one thing we can all agree on.”

Six months later, in January, my mom died and I begin to contemplate a new chapter for the house. When I ask Bernd for advice on how to attract wildlife, he becomes evangelical; he actually visits to advise me. He stops by with Lynn, after giving a talk to birders nearby. The moment they pull in, at 7:30 a.m., Bernd spots a bird—a dusty gray phoebe—bobbing over the lawn. He follows it: down the hill from the parking area, around a brick terrace, until there he is, my honored guest, standing under the barn, six feet away from the base of the privy. “It went in right there,” he says, pointing.

I can’t get enough of his accent. They-ah.

Soon he notes the abandoned start of a phoebe nest. It is graying and matted and set atop a support beam under the barn. It has been there for five or ten years, Bernd guesses, but I never noticed it. I have no memory of anyone at our house ever remarking upon a single bird.��

“You could open up that window there,” he says pointing, “and then maybe you’d have barn swallows. I’d also have a clearing around your house,” he continues. “But see this grass here?” On the steep slope to the brook, he means. “Just let it grow. Don’t worry about it.” Eventually, he says, bugs will settle amid the long stalks, then birds—indigo buntings, say, and chestnut-sided warblers—and then, finally, predators: mice, voles, shrews…

His advice is not revelatory; I’ve read his books. But his being there is something. This man is New England’s avatar of wild living, and I want to develop what he has. I want the ability to hear a whole story coded into a single chirp from a bird’s beak.

So in the weeks that follow, I open that window in the barn. I drag some brush out from the woods, to give juncos and chickadees a place to alight before fluttering toward the new feeders I’ve hung. And I watch this one bird I spotted with Bernd, a downy woodpecker perched high on the trunk of a maple, pecking away, a bright tuft of red at the nape of his neck. “He’s building the nest,” Bernd had told me.��

I begin checking that tree every morning, and for weeks—nothing. I’m crestfallen, and I say as much one day, writing a friend. But seconds after I hit send, I look out the window and see something red: Mr. Woodpecker himself, pausing on the trunk, then plunging into his hole—nesting, likely siring his brood. Right there in my own yard. I feel almost paternal.��

But then Bernd writes to say he’s raising a clutch of baby crows and deepening his rapport with a resident swallow family. “I spend hours watching them every day,” he says. He’s been on hand, beside their feather-lined nest, for the birth of five babies, and he’s been transfixed by something startling: the male is bringing in the feathers. “The usual avian sex roles are reversed,” he writes, in a fever, “and it means much else is different, too. And so I need to know every nuance of behavior from beginning to end.”

Attached to the note is a photo, taken by Lynn, of him sitting outside on the grass, in a chair, holding a white feather at arm’s length. His body language seems stiff, frozen. It’s a weird picture, I think. Until I see, frame left, the blue blur, the swallow, fluttering past tree branches and rocks and weeds, right toward Bernd Heinrich’s waiting hand.

Longtime ���ϳԹ��� contributor Bill Donahue () is the author of two e-books, and . is an ���ϳԹ��� contributing photographer.