Early in the morning, Davyd Betchkal is standing in the remote lowlands flanking the eastern slopes of Denali. Snow-capped peaks tower all around him; a river rushes nearby; a beaverÔÇÖs tail smacks the water; a vivid chorus of birdsong fills the air; wolves howl in the distance.

For the better part of eight years, this has been Betchkal's life. As the National Park Service's soundscape specialist in Alaska, he has been tasked with studying the parks' natural acoustic environment and determining the ecological impacts of human-made noise. With his assistant, Noah Hoffman, Betchkal has documented all 54 million acres of AlaskaÔÇÖs parks, which constitute some 60 percent of the total area of all 58 national parks.╠ř

Two things are clear to Betchkal: sound is crucial to the health of plants and wildlife┬áand everything from airplanes cruising overhead to the roaring of snowmobiles on the ground or the muffled ring of an iPhone in a jacket pocket affectsÔÇöand often disruptsÔÇöthe ambiance of our most precious natural areas.

“Listening helps people understand the importance of wild places,” Betchkal says. “It's really my first priority as an NPS ranger: making nature relevant to the American public. If it's not, these places will cease to exist.”

ThatÔÇÖs why the Park Service invested $3.2 million this year to better understand how sounds move around the parksÔÇömany of which experienced record visitation in 2016. Noise pollutionÔÇÖs impact is profound and varied, but also difficult to measure and even tougher to use to extrapolate solutions. At the tip of this venture is Betchkal, who has configured and installed an array of portable recording stations around Denali.╠ř

To be clear, in the context of natural places, birdsong isn't noise; the buzz of an airplane is. Sound, by contrast, is a protected resource under the Park ServiceÔÇÖs as part of the profile of a natural environment. According to by Park Service senior scientist Kurt Fristrup, a national park goer hears human-created noise, much of it aviation-related, during about 25 percent of his or her visit.

“Noise is just as ubiquitous and broad in its impacts on the continent as air pollution,” Fristrup says.╠ř

To be clear, in the context of natural places, birdsong isn't noise; the buzz of an airplane is.

Research has linked noiseÔÇöin particular, noise above 65 decibelsÔÇöto cardiovascular disease, elevated blood pressure, and poor sleeping patterns among humans. The Environmental Protection Agency, in fact, has . While it poses a greater risk in cities, it's increasingly become an issue in nature, too, especially when the noise from a propeller plane can easily top 80 decibels, which falls squarely in the threshold for hearing loss, .╠ř

Noise can be even more harmful for animals. published last year in Global Change Biology found that noise pollution can harm birds' abilities to communicate with one another, thereby leading to their migration away from their (now clamorous) natural environments. And according to a ╠řż▒▓ď╠řPLOS One, elk and pronghorn in Grand Teton National Park displayed a diminished ability to detect predators due to their decline in responsiveness as a result of increased noise pollution.

But before we can begin to solve these problems, we need a baseline of noise knowledge for each park. This is called a soundscapeÔÇöitÔÇÖs basically a compilation of extensive field recordings that capture both the birdsong and the plane engine. “The soundscape tells you the truth,” says soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause, known in the field for his pioneering work in field recording. “It gives you some incredible information about the relationship between humans and the habitat, based upon the ways in which human endeavor is affecting that environment.”

Though the Park Service was created in 1916, it wasn't until 2000 that a director there issued a mandate for soundscape preservation, by which time commercial airliners had been . Before then, “there was no logical, organized plan that was developed upon which to base the U.S. noise control policy” according to presented at the International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering. The basic idea was to develop a baseline for what unpolluted ecosystems sound like, then use it to measure how noise may interrupt or alter natural processes.

“Sound, just like the availability of nesting materials or food sources, is an important element of a productive natural system,” says Frank Turina, the NPS' program manager for policy, planning and compliance. “Activities such as finding desirable habitat and mates, avoiding predators, protecting young, and establishing territories are all dependent on the acoustical environment. ┬áWhen the acoustic environment is degraded by noise, these behaviors become more challenging.”

After the 2000 mandate, called Director's Order 47, the Park Service began setting up sound monitoring stations that  in parks across the country. While the early models were expensive and cumbersome, innovations in the design of the stations has allowed the NPS to increase its sound monitoring from two parks per year to upwards of 20, including Grand Canyon, Grand Teton, and Zion.

But Denali may be the most promising source of soundscape research in the parks system to date. It was among the first to begin taking inventory of sounds, in 2001. Betchkal took over the initiative in 2011 and, having now compiled his baseline data, is entering a ten-year monitoring phase that involves keeping tabs on the soundscapes and measuring the effectiveness of any future noise mitigation efforts in the park. “The inventory gave us a great idea about how sound changes with space,ÔÇŁ Betchkal says. ÔÇťThe monitoring should help us understand how sound changes in time.ÔÇŁ┬á

If all goes according to plan, BetchkalÔÇÖs data will be used to create ┬áof how and where sound will evolve and occur across the entire continent. They may help guide planning and policies concerning human-made sound. Once we have a baseline and register for a healthy soundscape, we can apply them anywhere, Fristrup says.

There are consistent patterns in sound levels across all the environments where the Park Service has taken recordings, Fristrup says. ÔÇťData from the southwestern deserts,ÔÇŁ for instance, ÔÇťcan inform predictions regarding eastern coastal parks, despite their manifold differences.ÔÇŁ┬á

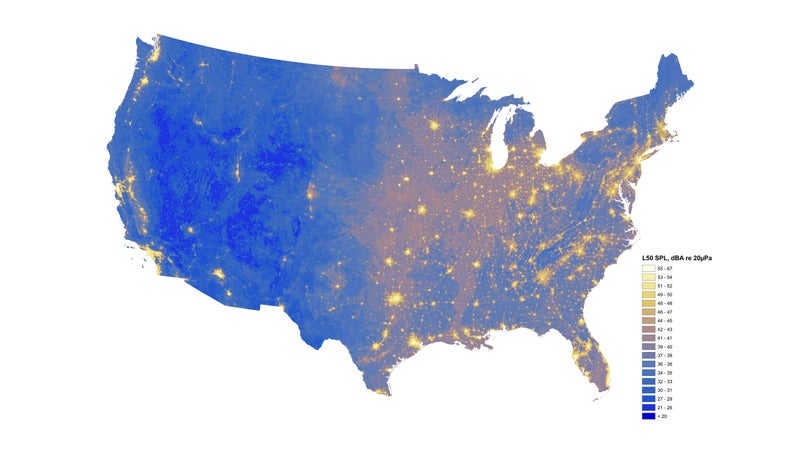

Betchkal's work will also serve the Park Service as it investigates ÔÇťthe consequences of noise exposure for things like human health, ecosystem function, social justice, [and] visitor experience,” Fristrup says. In more practical terms, that might mean studying whether low-income Americans bear the brunt of America's human-created noise pollutionÔÇöwhich comes, in large part, from airplanes.

In 2015, about 560,000 people visited Denali, a good many of them participating in flying sightseeing tours of the mountain peaks. In most of Alaska's parks, a visitor can expect to hear between ten and 20 planes flying overhead per day, according to Betchkal. When there are more than ten “noise events,” such as overflights, per day, true quietudeÔÇöthe absence of human noise for an extended periodÔÇöbecomes “vanishingly small,” he says.

Since 2000, the NPS had been working with the Federal Aviation Administration to develop air-tour management plans. But, due in part to fundamental disagreements between the two agenciesÔÇölargely concerning the sometimes competing interests of tourism and conservationÔÇöimplementation has been slow. Last year, however, the Park Service and FAA agreed to begin monitoring air-tour routes in FloridaÔÇÖs Biscayne and Big Cypress national parksÔÇöboth popular flight-tour destinations.

Meanwhile, leading soundscape experts havenÔÇÖt come to consensus on some foundational elements of the field, such as establishing appropriate terminology for characterizing the varying levels and states of noise and sound. But it seems everyone agrees on at least one thing: human beings are becoming more disconnected from the sounds of the natural world, and itÔÇÖs hurting us in the long run.╠ř

“We donÔÇÖt know how to listen,ÔÇŁ Krause says. ÔÇťWe have to quiet the fuck down.”