The Theft of Grand Staircase–Escalante

In 2017, the Trump administration announced that it was shrinking the iconic Utah national monument by nearly 50 percent. Leath Tonino devised a sketchy 200-mile solo desert trek, following the path of the legendary cartographer who literally put these contentious canyons on the map.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Deanna Glover’s voice hits a high note along with her eyebrows, tone and expression conveying the same grandmotherly concern.

She’s not my grandmother—we met for the first time an hour ago—but that hardly seems to matter to the sweet, white-haired 80-year-old. “Tell me you’ll have a friend hiking with you, because it’s a lot of country,” she says. “And, you know, I start to worry.”

The , in Kane County, Utah, is cluttered with arrowheads, wedding gowns, antique farm implements, and sepia photographs of the families that founded the town of Kanab in 1870. I phoned Deanna, a descendent of these Mormon pioneers, earlier this April morning, and though the museum, her baby and brainchild, was closed, she insisted on opening it so that the displays could inform my upcoming 200-mile, two-week trek through Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument.

Hiking with a friend? I shake my head, and a latent anxiety rears up, the prickly fear-thrill of engaging a desert that demands resourcefulness (drinking water found in sculpted potholes), extreme caution (camouflaged rattlesnakes in the middle of the trail), and a tolerance for solitude (my girlfriend, as I hugged her goodbye before leaving for Utah, told me to enjoy peeking into the recesses of my own skull).

Recounting this quip to Deanna, I notice the grip on her walker tighten. “Oh, I’ll be praying for you then,” she says. “I’m not kidding—it’s a whole lot of country.”

Ocher buttes, umber scarps, maroon hoodoos: whole lot of country indeed. Extending north and east from Kanab, the monument encompasses one of the gnarliest stretches of the lower 48. To borrow writer Charles Bowden’s apt phrase, it’s “the heart of stone.”

Ever since President Clinton established the monument in 1996, it has been contentious: old-timers versus newcomers, Republicans versus Democrats, advocates of using the land versus advocates of protecting it (as if these were mutually exclusive agendas). Conservative politicians in pressed blue jeans and blazers tend to see it as an affront to economic growth. Dirtbag adventurers in Chaco sandals deem it one of the epicenters of North American slot canyoneering. In Kanab, mention Edward Abbey, the Southwest’s iconic nature writer, and you’ll receive either a high five or a tirade, depending on your interlocutor.

The latest dispute began on December 4, 2017, when President Trump cut the nearly 1.9-million-acre monument into three units, reducing the overall protected area by almost 50 percent. The White House’s stance, as outlined in the official proclamation, was that the Clinton administration had designated far more terrain than the law allowed. Deposits of coal, oil, and natural gas played no part whatsoever in the decision, obviously. Environmental organizations immediately filed lawsuits, arguing that Trump lacked the authority to shrink an existing monument. Nevertheless, the Bureau of Land Management went ahead and drafted several plans, one of which, if implemented, would open almost 700,000 acres to mining and drilling. With the final decision on those plans tied up in court, nobody can predict whether the original boundaries will be reinstated.

My interest in the place is personal. Working for the Forest Service in my twenties, I resided in a cabin an hour south of the original monument: bought my groceries in Kanab, thrashed myself silly every weekend in the intricate backcountry of arroyos and yuccas and coyotes. It was upsetting to picture the wilderness ransacked for profit, to sense my cherished memories of the region disappearing into the abstraction we call news.

Thankfully, I didn’t forget Almon Harris Thompson.

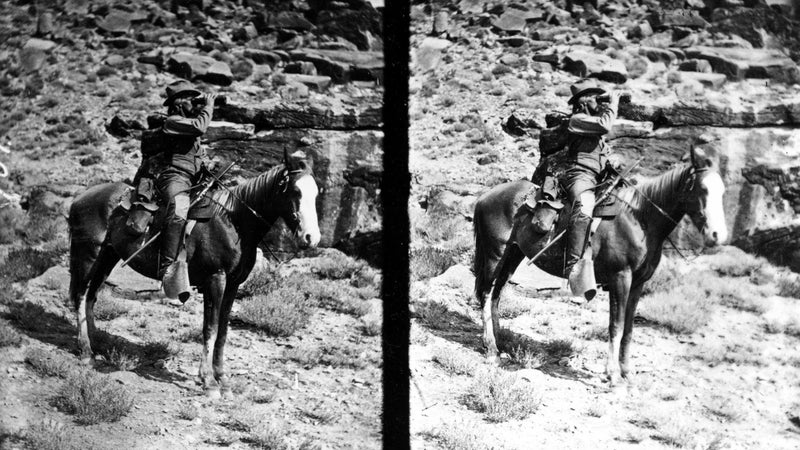

Nicknamed Prof, Thompson was a school-superintendent-cum-cartographer from New England who wore a bushy mustache, abstained from smoking tobacco, and, according to a colleague, was “always ‘level-headed’ and never went off on a tangent doing wild and unwarranted things.” John Wesley Powell, the Civil War veteran famed for boating the Grand Canyon’s whitewater in 1869, was Prof’s brother-in-law and boss. Together they were employed by the federal government; a congressional appropriation funded their brave, meticulous research into the geography of the Colorado Plateau’s remote canyonlands.

Remote is an understatement. An 1868 map indicated a massive blank space in this area of Utah. In 1872, at the age of 32, Prof led a small party into the unknown country. The final river to be named by the U.S. government (the Escalante) quenched his thirst that spring, and the final range to be named (the Henry Mountains) registered his horse’s hoofprint.

Emotions rarely inflect the spare prose in Prof’s diary, a document devoted to mileages, elevations, the shapes of watersheds, the dips of strata, and, tangentially, cold rain and “a sort of dysentery attack.” What does come through, however, is a seriously badass route that, by chance, flirts with our modern monument’s boundaries, weaving in and out of both the Clinton and the Trump versions.

For the next two weeks, I’ll attempt to retrace Prof’s route (he took roughly 25 days), mostly by walking, occasionally by hitching. The itinerary that earns Deanna’s worry has me heading northeast from Kanab: up Johnson Canyon, past the Paria amphitheater to the Blues badlands, along the headwaters of the Escalante River, through the Waterpocket Fold, and, finally, over the 11,000-plus-foot Henry Mountains. In my pack I’ll carry a sleeping bag and headlamp, two single-liter water bottles and a four-liter reserve dromedary, and not much food besides instant coffee, pita bread, and salami. Hopefully, beer and potato chips will greet me at the few and far between gas stations—in Cannonville (pop. 175), Escalante (pop. 802), and Boulder (pop. 240). I’ll lug no tent, no toilet paper, no GPS, no smartphone.

The goal is to drop below politics—to find, and hear out, the lovers of this unique landscape. Even better, to drop below conversation, below language, and viscerally, with my ache and my thirst, contact the land itself.

April 10 is my departure date, until it’s not.

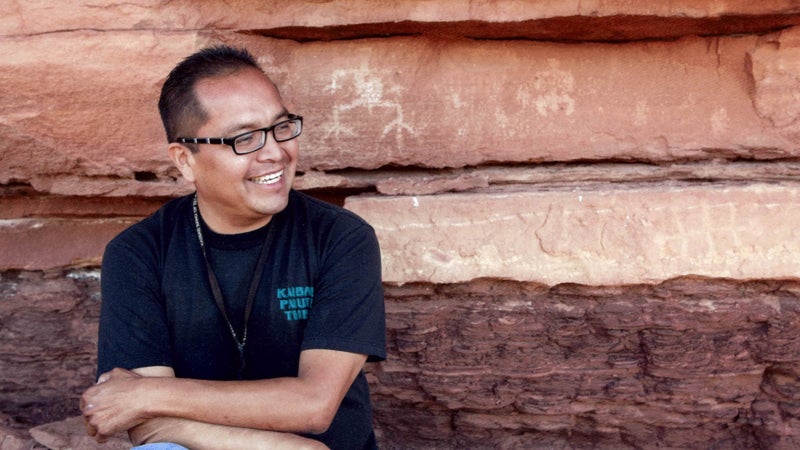

The visit with Deanna runs long, so I decide to spend the afternoon riding shotgun beside 43-year-old Charley Bulletts, the soft-spoken, quick-to-laugh cultural-resource director of the Kaibab Band of Paiutes.

A local boy, Charley left for a spell—tried his luck in Cedar City, Utah, and Mesquite, Nevada—but now he’s home for good, raising his kids in the same desert where he was raised. His late grandfather was one of the last medicine men of the tribe. If the Kanab Heritage Museum situates the monument within a frontier context, Charley’s perspective, which he shares as we drive the outskirts of town, links it to an even deeper oral history.

“This is so bad it’s comical,” he says early in our tour, parking with the windshield framing a cartoony mural on a supermarket’s cinder-block wall. The painting depicts a procession: covered wagons, livestock, dogs, young men carrying rifles. “I get a kick out of it, I really do—the happy Mormons entering an ‘unpopulated territory,’ following their destiny.”

The Southern Paiutes have inhabited this region since time immemorial, and their songs make reference to woolly mammoths and flowing lava. For generations the rhythm of human life was, by necessity, synchronized with the rhythm of the seasons: when the rabbitbrush turned yellow, the piñon nuts were ready for harvesting. The modern concept of private property, unsurprisingly, didn’t exist. “Fences did it,” Charley says. “After they sprang up, and we crossed them, and we got shot at numerous times, then we understood that land could be owned.”

Charley elaborates on this difference in worldview. “With European culture, it’s pieces of paper that tell who you are and where you come from—your birth certificate, your deed, or whatever. But for my people, tradition instructs us that once your baby’s umbilical cord comes off, you have to put it under either a young tree or an ant pile. That way your kid can be connected to a place.”

He shifts the truck into gear, and momentarily we’re part of the wall’s cartoony procession. Then we’re cruising, our talk gaining momentum: tortoises, earthquakes, prejudice, fisheries, alcohol, dams.

I ask about the monument, and Charley answers with grim humor. “If we let this man, this businessman, run the country, the end of the world might come earlier than we want.” But we spend less time discussing current events than talking about, as Charley says, “old ones.” After discussing the and pausing at a site where a reburial ceremony was held, we pull into a gravel lot overlooking a reservoir. Charley’s grandfather used to tell of certain spots along the road where he’d seen spirits, places you wouldn’t want to change a flat alone in the dark. Perhaps this is one such location; the remains of 53 bodies were unearthed here during construction.

It doesn’t look like much, metaphysically speaking. Swallows fly with their reflections. Pebbles line the shore. Kanab’s buildings stand toylike in the distance, backdropped by blocky red ledges. But this nondescript quality, I suspect, is the very point: everything isn’t visible to everybody. I try to envision the scene in the spring of 1872—a timber stockade and a scattering of adobe houses, Prof sorting supplies, tinkering with his theodolite, glancing up and out, seeing a problem to solve, a mapmaker’s challenge.

Charley nods at the horizon. “People always say, ‘Oh, it’s desolate!’ But no, that’s not desolation. Spirits live out there. Beings live out there.”

Out there.

It’s where I’m aimed. Tomorrow.

Strolling the paved road in Johnson Canyon the next morning—the road that leads past the Vermilion Cliffs and the White Cliffs, lower steps in the gigantic topographical staircase for which the monument is partially named—I walk by some of Trump’s scissor work. This zone east of the road still appears unaffected: no drill rigs, no ATVs tearing cryptobiotic soil crust to hell, no indication that the tilted slabs and twisty junipers have undergone a transformation. Says a sudden voice in my already-getting-dehydrated brain: A cut on paper draws no immediate blood from the earth.

A dozen parched, solitary miles later, I top out the White Cliffs, turn onto Skutumpah Road, and soon after slump down in a heap, the 85-degree heat having taken its toll. Pure serendipity: a dented white pickup with a cooler tied to the flatbed eases to a stop alongside me. Forgoing the usual hello, the driver mentions that people like him might not get a lot of ranching done, but they sure are good at leaning against the truck with something cold at sunset. It’s the long day’s second voice, and it belongs to Quinn Robinson. I hobble over on blistered feet for a Gatorade dripping with ice slush.

“Suppose I’ve been anywhere you can see,” Quinn says, gazing across a rolling sagebrush bench bordered to the north by the Paunsaugunt Plateau’s limestone ramparts (the rim of Bryce Canyon National Park) and to the south by endless violet sky. “With our few hundred acres private and the permits, well, I couldn’t say how much land it adds up to.” He rubs his forehead as if to massage loose a number. “Put it this way: five hours on a horse east from the ranch house, two hours south—we summer our 250 head on all that.”

The ranch house—renovated by his dad atop the foundation laid by his great-granddad—is about two miles off, down in a hollow, spitting distance from the monument’s western edge. Quinn was homeschooled there, but he skipped grades seven and eight, because “you learn more working.” He’s 23 years old and has 22 years of cowboying to his name, give or take 12 months.

Between tilts of Gatorade, Quinn articulates, without a hint of frustration, the numerous frustrations of keeping the family ranch going: ramping land prices, scarcity of available grazing allotments in the monument, the need for a couple of sidelines (he’s got a degree in welding). Great-granddad Malcolm ran a herd of 1,000 cattle on the Skutumpah Terrace in the early 1900s, but around here that kind of open-range operation is out of reach in the 21st century.

Regardless, the dream of an uncomplicated time persists. The Robinsons, Quinn tells me, would prefer to manage their home landscape for “productivity,” without government agencies butting in and “locking things up.” They favored the monument’s reduction, hoping it would put more acres in play. “But it didn’t help us anyway,” Quinn says, “because the cuts weren’t around here.”

That’s it for political talk. The sun is now sinking through a scrim of clouds, patches of ground—50 feet away, 15 miles away—pulsing with a peachy light. For a while, nothing moves but that light, including our conversation. We’re mesmerized, entranced.

“Love’s kind of corny, but I do love it.” Quinn gives the cooler a friendly pat, breaking the spell. “And it’s not only the land. You get on a horse and ride the same places your dad rode when he was your age, and his dad rode, and his dad rode. You call them by names passed down the generations, names that aren’t on any map. You do the same chores, maybe think the same thoughts. Shoot, it goes back and back.”

He hops in the truck and suggests a nearby campsite, a protected cove along Thompson Creek. Black exhaust uncoils from the tailpipe and I’m alone. Sort of.

Thompson Creek? I’d almost forgotten about Prof. Sure enough, there’s the name on my USGS quad, labeling a blue thread that enters the monument just beyond the Robinsons’ ranch house. And there also is the day’s third and final voice, speaking up to me from one of the diary pages I photocopied: “Friday, May 31. Broke camp at 8:00. Traveled 16 miles by 3:00, when we came to a beautiful valley with a fine cool spring in it, and we camped.… Country over which we have passed rather rough.”

According to a friend of mine from Boulder, a speck-like village in the heart of the heart of stone, the roads in southern Utah follow pioneer trails, the pioneer trails follow Native American footpaths, the Native American footpaths follow bighorn sheep tracks, and the bighorn sheep tracks follow faults, breaks, creases—any available weakness. It’s an elegant schema, an image of travelers stacking through time. Whether you’re Prof in 1872 or Wannabe Prof in 2018, stubborn bedrock is in charge, pushing this way and pulling that, providing scant options for forward progress.

I leave Thompson Creek at 8 A.M. on April 12, eager to knock off a significant chunk of Skutumpah Road. A mere 17 seconds into the march, though, an employee of , an outdoor treatment facility for troubled teens, offers me a ride, and despite the pep in my step, I jump in. Jouncing along, my chauffeur, Teague Perkins, mentions that “there are 60 kids in the monument as we speak, sitting with their thoughts, some of them detoxing.” She also mentions a “magical” denizen of the canyons, a luminescent deer-man hybrid named the Guardian who watches over the land.

Fifteen minutes later, Teague drops me at a trailhead so that I can make a detour into the narrows of Lick Wash, a gorgeously cross-bedded feeder of the Paria River. By the time I return to Skutumpah Road, the morning’s warmth has been replaced by a chill. During the next six hours of walking, it gets colder.

That night I make camp in what feels like 40-mile-per-hour gusts and a sideways snow squall. Hunkering, shivering, I curse myself for underpacking. I toss and turn, waiting for the darkness to give so that I can pull my sneakers on and go.

The upside to creeping hypothermia is that it cracks the whip. I make 15 miles by noon of day three, descending into the Paria amphitheater, a shattered, rainbowed, kaleidoscopic basin, at the bottom of which sits the hamlet of Cannonville. Christa Sadler, who I’ve arranged to meet at the town’s BLM visitor center, is running ahead of schedule, and she passes me in her pickup. Window rolling down: “It—is—blowing!” Blond hair tangling with dangly turquoise earrings: “Get—in—here!”

A science educator and environmental activist based out of Flagstaff, Arizona, 56-year-old Christa swung a paleontologist’s rock hammer in the monument before it was designated as such. Specifically, she swung that hammer in the Blues, a roughly 2,000-foot-high barricade of fractal badlands adjacent to Scenic Byway 12, some 15 miles east of Cannonville. We camp there, sharing the misery of another bitter night, and rise early on April 14 for an excursion into the unknown country of prehistory.

Christa requires no caffeine to jump-start the day, her manic energy firing nonstop. “Fucker,” she shouts, her hand forming a fist around a rolled map that highlights Trump’s cuts. We’re sorting supplies on the truck’s tailgate, loading snacks and sunscreen into her daypack. “Where is the monument? Are we even in the monument anymore? Honest, I’ve never cursed so much as in the past 18 months.” She musters a fresh batch for emphasis, unrolling the map.

Our plan is to reconnoiter the Blues, the core of which remains protected, the northwestern corner of which has been excised. The Kaiparowits Formation represents, arguably, the planet’s best record of terrestrial late-Cretaceous ecosystems, while the Straight Cliffs Formation below it represents, to some, a profit in the offing. Christa has published a book about the monument’s superlative paleontological resources (more than a dozen unique dinosaur species identified over the past couple of decades), and she knows plenty about the coastal swamps that deposited copious organic matter (i.e., future coal) in the Straight Cliffs Formation. Hence her breathless venting as we strike off for six hours of scraping around in the Kaiparowits dirt.

Inhale. “I’ve rafted the Grand Canyon about 90 times, educating other rivergoers and whatnot, but this place is extra special to me, because there’s still so much to discover.”

Exhale. “I don’t have kids. This place is where my love goes. This place.”

Inhale. “What’s happening to the monument has been worse than any of my breakups, ever. Problem is, instead of wanting to kill myself, with this I want to kill someone else.”

Exhale. “OK, let’s set the crap aside for a bit and prospect. I could use some prospecting.”

Prospecting is the search for fossils, plain and simple. Our outing, which yields hundreds of petrified-wood shards, dozens of clamshells, and three bits of dimpled brown turtle carapace, requires a peculiar style of ambulation, a unique mode of being. To prospect, abandon the trail. Blur your eyes. Meditate on the delicately patterned, crumble-at-the-slightest-touch ground. Meander and scan. Scan and meander. Stay loose, easy, open to whatever might emerge.

“It’s called float,” Christa says. “That’s our name for the stuff eroding out of these slopes and floating to the surface, indicating there might be something worth digging for nearby.”

“The float zone,” I say.

“The float zone,” she echoes. “You’ve got to get in that headspace.”

This coinage inspires her to share an anecdote about prospecting the Blues in the late 1980s, era of the Walkman and cassette tape. Alone, classical music crescendoing in her headphones, she wandered away from the so-called real world and temporarily lost herself in the realer world: the textured earth and possibility. That the anecdote doesn’t mention a jaw-dropping find—say, a new-to-science dino skull—strikes me as significant. The point is just being out, in, and with the land.

Memory transports Christa, and when she returns, the morning’s cursing and the outrage and sorrow are absent. “I can never come out here too often,” she says. “Never.”

But where, I’m soon wondering, is out here? Consulting the map, I can’t tell whether we’ve veered from the protected section of the Blues into the BLM’s open-for-business lands. It all appears of a piece. For now.

Christa invites me to join her and some fellow paleontologists for dinner that evening in Escalante, 19 miles east of the Blues. I hem and haw—I’d not expected so many rides—but the offer is too interesting to pass up. Notwithstanding Prof’s disciplined leadership, my trip is taking a turn toward the random, and I spend two days in town. On Sunday, exiting Escalante, I chat with an octogenarian historian who suffered a stroke and struggles with the Prof anecdotes he recounted confidently in his prime. He and his wife, the gentlest of couples, longtime critics of the monument, insist that I spend the night in their guest bedroom.

Finally, on Monday, I once again roam the backcountry alone—Antone Flat, Death Hollow, nameless slickrock alcoves. After 17 miles I’m back on Scenic Byway 12, pounding pavement. An ache develops in my hip, disappears, reappears, doubles down. The ache swaps hips. I take it easy—feast on my remaining salami, sleep 11 hours, spend the bulk of an afternoon journaling—before limping onward, ever onward, into the unknown country of the 21st century.

Day ten, lips chapped to splitting, nostrils scoured bloody by relentless blowing grit, I crash at my friend’s home in Boulder, the speck-like village surrounded by incised tributary canyons of the Escalante River that, according to Prof, “no animal without wings could cross.” Wait a second. Do I have wings? How did I get here? And is this whiskey in my mug? I’ve slipped into a state of dopey detachment. Increasingly, I’m losing the sequence, the order: Tropic Shale, woman who feared I was lost; Dakota Sandstone, man who rooster-tailed me with mud.

“You’ll flip for Grant,” my friend says, pouring another dram.

I drain it. The hip tingles.

“Really, Grant has the Escalante’s nooks and crannies in him like nobody. Wait until you see his house.”

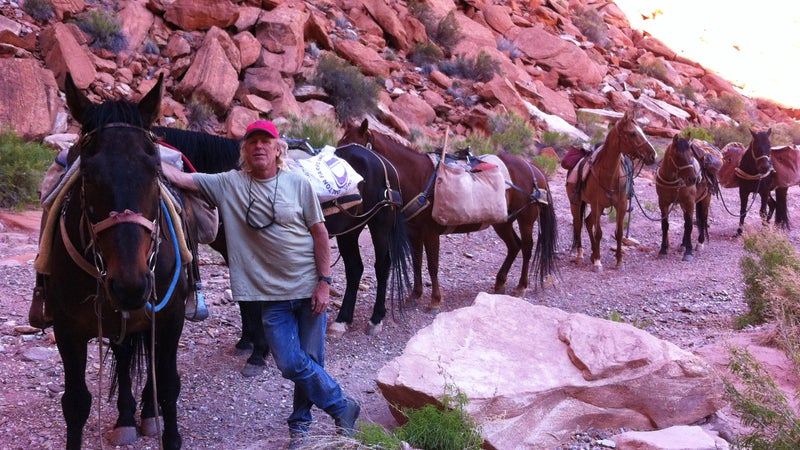

Grant Johnson has been exploring the Escalante canyons since 1975, and for 22 of those years, while running a horsepacking guide service, he spent five months annually in “the wild spaces,” as he puts it. Working sporadically during his winters off, the chip-toothed, barrel-chested 62-year-old dynamited an orange bulb of Navajo sandstone to create a network of hollows that he calls home: den with bookshelf of obscure geology tomes, jam room with PA system and harmonicas, larder brimming with foods harvested from his Deer Creek homestead. Totaling 5,700 square feet, the dwelling feels nothing like a dwarf’s dank hovel and everything like Architectural Digest melded with The Flintstones.

It’s April 21, day 11. I snagged a ride here from Boulder with my friend, the two of us peering into a mad frenzy of snowflakes. Prof didn’t swing this far south—he kept to the Aquarius Plateau, a forested behemoth hidden this morning by swirling gray weather, making an ascent less than appealing. No part of me regrets deviating from Prof’s historic route, perhaps because I’m a wimp, perhaps because I bedded down on the deck last night and woke soggy, the duct-tape patches on my ratty sleeping bag not exactly waterproof. To understate the case, I’m totally psyched to be a guest of Grant’s sheltering caves.

“There’s only one suspect crack in the whole structure,” he says, craning his neck, inspecting the nearly invisible fracture with a squinting focus. We’re perched on stools at the kitchen counter, a bazillion pounds of sand swirling in ancient compressed stillness above our heads. “But heck, my life will be over before the thing collapses.”

About that life: it’s eclectic, an obsessive passion for the unknown country’s hideaways (obscure pictograph panels, secret springs) lending coherence to what might otherwise appear a random mishmash. Grant landed in the region as a teenager, taking quarters off from college in Washington State to apprentice with itinerant uranium miners. He cofounded the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance in 1983; for his activism he was hung in effigy by the anti-enviro faction in Escalante, more than 40 miles away. He built roads and fought the building of roads. He stabilized Ancestral Puebloan ruins alongside professional archeologists and hauled supplies for AmeriCorps crews eradicating the invasive Russian olive.

“Everywhere that I hadn’t been was my goal,” Grant says. He passes me a bowl of steaming black beans enriched with salsa from last summer’s garden and bacon from his former pet pig. “But there’s too much for anyone to know it all.”

I’m enjoying the restful lunch, but Grant’s antsy; the sunshine burning off this morning’s overcast seems to remind him of neglected chores. “I better get my ass busy and milk the cow,” he says, not getting his ass busy. Unfolding my map prompts him to unfold a map. Shortly, the counter is papered with hogbacks and rincons, features labeled Lamp Stand and Woodruff Bench, and we’re nerding out on the minutia of Prof’s journey.

“I haven’t used a topo in ages,” Grant says, explaining that, fundamentally, it’s the mystery of the wilderness he’s after—the beauty of the mystery.

He slides his index finger across the overlapping maps: east from Deer Creek along the Burr Trail road, out of the monument, through the warp of the Waterpocket Fold (centerpiece of Capitol Reef National Park), up to the crest of the Henry Mountains. The finger pauses there, as if catching its breath.

“Dude, I seriously do need to get my ass busy and milk,” Grant says. “Aw, but can you imagine? Can you imagine this in 1872?”

“I’ve been trying,” I reply.

“Me, too. Since I was a teenager.” He lifts the finger. “It’s pretty much all I’ve done.”

Days. They pass. And I pass through them, trading the monument for Dixie National Forest, the forest for Capitol Reef National Park, and the park for Notom-Bullfrog Road, which parallels the eastern flank of the Waterpocket Fold. On the 14th day out from Kanab, instant coffee flooding my bloodstream and the Henry Mountains looming, I’m hit with a dual realization. One, the trip is concluding, Prof soon to spin a 360, absorb the panoramic view, ink his understanding onto one of the American atlas’s remaining blank spaces. Two, this conclusion must for me be mute, inarticulate, the time arrived to shun characters, perspectives, varieties of dedication and fascination and love.

Grant was the last local whose story I heard, more than 48 hours ago. My hip is throbbing again, the temperature is climbing into the eighties, and I’ve got 27 nonnegotiable uphill miles to make. I’ve been planning this grueling ending since the beginning: trudge a knobby BLM road through gulches and rimrock, bushwhack the scraggly forested slopes above Pennellen Pass, gain the alpine ridge of Mount Ellen’s south summit (named for Prof’s wife).

Sneakers laced tight, I hike the complex mess spilling from the Henry foothills for five, six, seven hours—squiggly passages with vertical walls, scorched mesa tops, mauve and dun and apricot soils. Prof’s diary consistently downplays challenge and travail. (“Could not find trail so went up canon exploring side canon. Find trail out. Have not found one yet.”) But an assistant’s report mentions that around this point, the party pickaxed notches into the cliffs and wedged their shoulders against the equines’ rumps to heft them over various impediments. Referring to southern Utah’s contorted topography as a maze is lazy and clichéd. That doesn’t alter the fact that it is a maze.

Painfully, by inches, the dark mass of Mount Ellen nears, resolving into detail: conifers, talus chutes, wizened snowbanks. I apply myself to the task of making those details more detailed and, simultaneously, quieting my brain with exhaustion. For some reason, though, in spite of the heaving effort, my brain won’t quit. At tree line, the range’s crest an hour distant, the symbolic finish line so close, I’m still occupied by words.

People think they have the monument pegged, what it’s made of and, accordingly, what it should be made into: a coal mine, a cow’s supper, a preserve for scientific investigations, a stirring wilderness experience, an anchor for family history, a sacred grave to receive our prayers. The list is long, so long. But if enough people know something, and if they know that something differently, is that something actually known? If I’ve learned anything from two weeks of walking and hitching—two weeks of listening, both to people with my ears and to the ground itself with my ache and my thirst—it’s that there are layers upon layers to this famously stratified land. Always more layers. Untold layers. And that to interpret the place via a single layer is to miss the place entirely. To know nothing whatsoever of the truth.

So goes my little monologue, a distraction from ragged lungs and cramping quadriceps. At dusk I achieve the desired spot—the mental spot (blank mind) and the physical spot (pad of crunchy grass straddling the mountain’s narrow spine). I’m dazed, depleted, barely able to spread my sleeping bag, entirely unable to wrap my belief around the scale and power of the scene. The new monument sprawls within the sprawling old monument. Both monuments sprawl to the horizon and beyond. Limitless naked desert, as I remember it from my twenties, as I hope to always remember it, is here beneath me and before me: strange, spooky, utterly unknowable, utterly unknown.

I can feel Prof close, scribbling in his diary, disagreeing: “Sunday, June 23rd. Fred sketched our trail since leaving Kanab. Got it done at 5:00 P.M., when we started on our way back.” Not wanting to interrupt, yet unable to withhold comment, I speak to him, whether aloud or just internally is difficult to say. You tried your best, buddy, but you failed. You had to fail. Look at this. Look at this. There was no possibility of succeeding.

And then, at last, the words really are gone. The view is saturated with black, the black sparking with stars.

Leath Tonino wrote about snowplow drivers in March 2017.