Perhaps you, like me, have been getting flooded by Earth Day ads. They scream that there is so much you can do to save the planet. Pay money to plant a tree! Come to a Zoom meet and greet with tech bros who are making sustainable apps! Watch NASCAR drivers race a supposedly carbon-neutral car! Buy a sustainable cooler to carry your reusable wine tote for your zero-waste picnic in the park! Once you’re there, you can grill with new, sustainable charcoal and eat new, sustainable peanut butter! You didn’t forget to wear your eco-friendly socks, did you?

It feels like a parody, underscoring just how performative Earth Day has become right when we need meaningful action. A third of Americans have been hit by climate-related disasters in 2022, from hurricanes and wildfires to extreme cold. This month’s , a climate assessment published by a group of leading scientists brought together by the United Nations, outlines how we might mitigate climate change’s worst impacts. It states that greenhouse-gas emissions must peak within the next three years and then drop in half by 2030 to avert catastrophe. To achieve that, according to climate scientist Kim Nicholas, developed countries will need to reduce emissions by about 1 percent each month for the next seven years. Having the right type of picnic accessories, then, isn’t going to make much of a dent.

We do have the science, technology, and funds to work toward those goals—the cost of clean energy, for one, has plummeted. And despite the vociferousness of climate deniers on social media, public concern about climate change is higher than ever. What we don’t currently have is political will and action. As the IPCC report lays out, surprising nobody, political inaction and corporate resistance to change are the primary obstacles toward a livable future.

It’s easy to give up hope in the face of a gridlocked Congress and oil maneuvering after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But before you do, remember that Earth Day was conceived during a similarly tumultuous time yet still managed to create urgency and meaningful results for the environment.

The Very First Earth Day

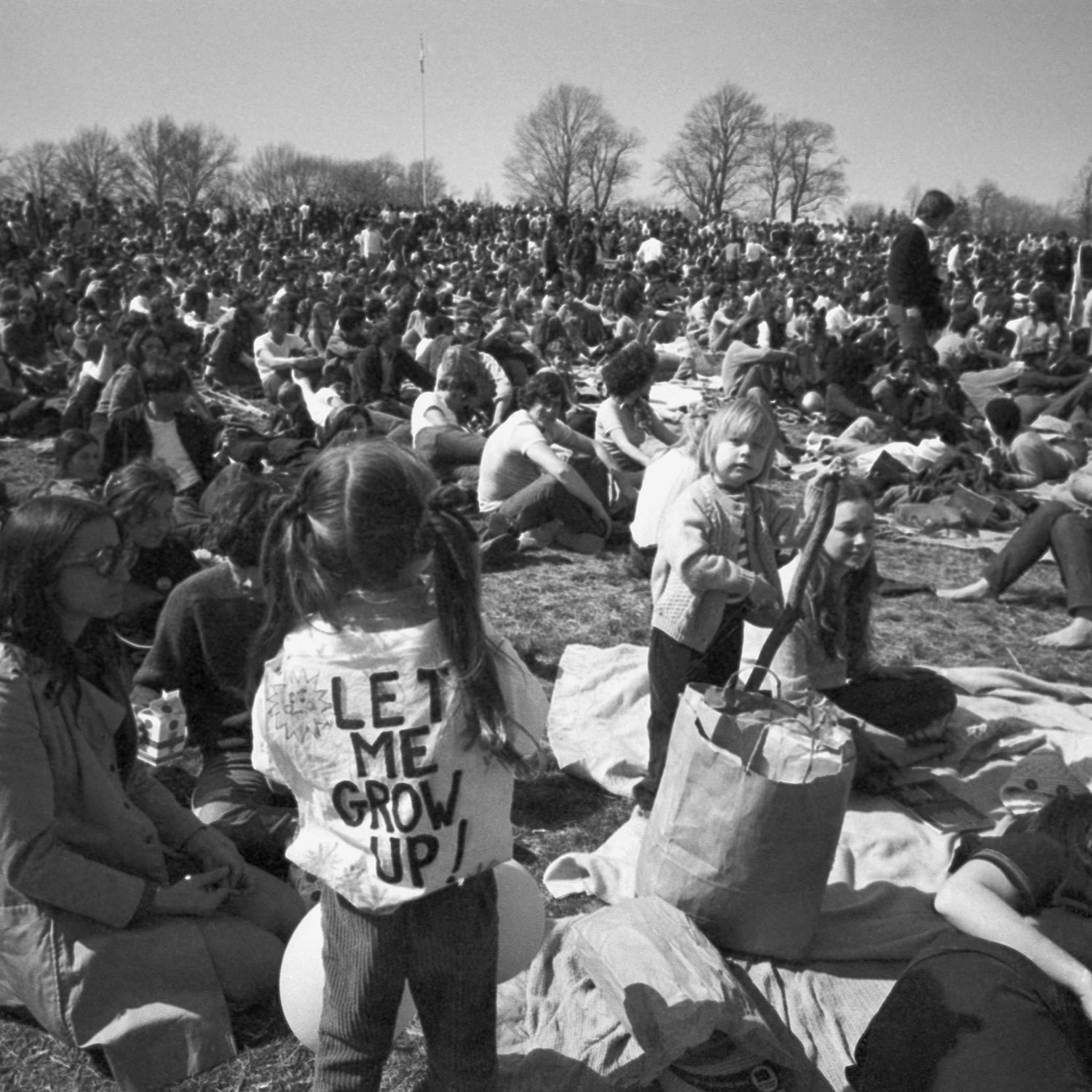

Denis Hayes at the Harvard Kennedy School when he was tapped by Gaylord Nelson, a Democratic senator from Wisconsin, to organize the first Earth Day, in 1970. At the time, rivers were on fire and birds were dying off en masse due to air and water pollution. Other big issues were at play, too: Vietnam was tearing people apart, and events like the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy and the Stonewall Riot had inflamed cultural divides and kept the public on edge. Despite that, 10 percent of the U.S. population took to the streets and protested the destruction of the environment on that first Earth Day.

Change wasn’t immediate. A week afterward, Nixon started bombing Cambodia, and the week after that, the National Guard shot protesters on the campus of Kent State University. “The last thing on anyone’s mind two weeks after Earth Day was the environment,” Hayes says.

But in the following months, he and other activists founded the , targeted specific politicians and policies, and spearheaded a wide-ranging letter-writing campaign. Within the next few years, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Endangered Species Act, and established the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with a host of other protective measures.

I asked Hayes, who still works in environmental advocacy, what lessons we all might learn from that first Earth Day to help steer us away from socks and charcoal and toward meaningful carbon reduction. Here are his ideas.

Keep Your Eye on the Ball

Hayes says that one of the advantages they had in 1970 was “nice discrete problems with nice discrete solutions.” Air and water pollution were tangible and coming from traceable sources, which made them easier for the movement to focus on. The problems we face today aren’t as straightforward—environmental degradation is coming from multiple angles. But as the IPCC report states, you can still boil down the threat to livability on our planet to two greenhouse gasses: carbon and methane.

There are many other issues we can and should face (including continuing to protect species and address pollution), but at this point, we need to focus our biggest efforts on the biggest issue: emissions.

Know Thy Enemy

“It’s a universal truth that people are most easily mobilized when there is a clear enemy,” Hayes says. In the late ’60s, it was pretty clear who was causing air and water pollution because we saw smokestacks pouring into the atmosphere.”

He worries that sources of emissions are less visible and specific today. But the IPCC report also calls out the clear villains—fossil-fuel companies and the politicians who have enabled them—and cites them as the biggest barriers to addressing climate change. The IPCC authors have given us guidelines on who to target with our votes and dollars and who to push for action. It’s not your nonbiodegradable picnic basket that’s the problem, so don’t waste your effort there.

If You Don’t Like the Politics, Change Them

In the U.S., we’re currently mired in a system where on the margins between parties can have a huge amount of sway in blocking legislation. To hit those emission-reduction goals, we need to pass some kind of sweeping climate legislation ASAP, and the upcoming midterms don’t look particularly promising for climate advocates.

But, Hayes says, one measly politician can also make a positive difference. In 1970, Earth Day activists targeted “the dirty dozen”—congressmen who had opposed environmental action and who were in flippable districts. Their efforts unseated seven of the twelve by small, strategic margins, sending the signal that voters were making choices based on environmental issues. “That was a shot heard around Capitol Hill,” he says. The month after that election, Congress passed the Clean Air Act.

Don’t Worry About Being Perfect

Hayes says that passage of the Clean Air Act can instruct current climate advocates, who he worries are getting too caught up in the details. “The Clean Air Act was an imperfect vehicle, but it did dramatically change air quality,” he says. “You can have something that looks elegant on paper, but if you can’t pass it, it doesn’t do you any good.”

Also, regulating emissions doesn’t just have to happen at the federal or international level, Hays says. Local energy codes and vehicle-emission standards are often easier to implement and scale up. “Take the imperfect thing and move forward,” he says. “We’ve got to create momentum that says, ‘We’re chipping away at this.’”

Give the People Something to Believe In

Speaking of moving forward, Hayes worries that some of those at the front of the current climate movement are talking too much about the (very real) consequences of inaction and not enough about the profound, lifesaving benefits of climate action. “It’s hard to get people to engage around something that seems hopeless,” he says. Back in the seventies, they could point voters to the benefit of clean water and air, which felt tangible and good. Now, we need to point positively to the ways we can use the technology we already have to electrify energy and transportation, cut carbon and methane emissions, and stop funding fossil fuel production. Now we need to point positively to the ways we can move away from fossil fuels, switch to clean energy, and make the places we live healthy and resilient. We’re on a razor-thin edge of viability, but we have the tools to right the ship.

We just need the action.