LIKE MOST PEOPLE, I’ll rubberneck at a house fire if I happen to be passing by. Wildfires, though, can pull me in from the next county. I spent five years during my late teens and early twenties cutting firebreaks with a hotshot and engine crew for the U.S. Forest Service, and the smell of burning pine can make me wish I was back on the line.

Fire Truck

The Valle Grande, a major grassland in the Valles Caldera National Preserve, took a direct hit

The Valle Grande, a major grassland in the Valles Caldera National Preserve, took a direct hitFire Map

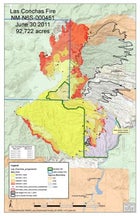

Fire Map, Los Conchas Fire on July 1, 2011

Fire Map, Los Conchas Fire on July 1, 2011Las Conchas Fire

The fire burns above Los Alamos on Sunday night.

The fire burns above Los Alamos on Sunday night.Las Conchas Fire

Flames bear down on Los Alamos Thursday night.

Flames bear down on Los Alamos Thursday night.When northern New Mexico’s Las Conchas fire erupted on Sunday, June 26, the gigantic plume of smoke billowing off the Jemez Mountains looked terrifying and ugly, like motor oil smeared across the sky. After sunset I drove to a lookout spot near my home in Santa Fe, where şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř is based, and watched a wall of flames six miles wide roaring down the southern and eastern flanks of the Jemez range, 20 miles west of where I stood. I had to go see it for myself.

The Forest Service is generally leery about letting journalists tag along with firefighters. Unlike the military, which regularly embeds reporters with front-line troops, it doesn’t see any upside to having untrained onlookers hanging around in a war zone. But Michael Thompson, an assistant chief for the Los Alamos County Fire Department, agreed by telephone to let me join him for a patrol of the firelines on Monday afternoon. “Get to Los Alamos before they block the city off,” he told me. “The town’s evacuating.”

In less than 20 hours, the Las Conchas fire—which started roughly 12 miles southwest of Los Alamos—had consumed nearly 50,000 acres and closed much of the gap between its point of origin and the town, an incredibly rapid march. Midday Monday, the fire was already threatening to enter this small but well-known community of 12,000 people, most of whom are among the 15,000 nuclear scientists and support staff who work at the adjoining Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). By 3 p.m., I was speeding west with şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř senior editor Grayson Schaffer. A steady stream of cars were coming from the other direction, fleeing the tightly controlled hilltop citadel. Over our heads, a mushrooming column of smoke reached into the stratosphere.

We met Thompson in a high school parking lot off Trinity Drive, named for the site where the first atomic bomb was tested in 1945. (Other Los Alamos streets bear familiar names: Oppenheimer Drive, Bikini Atoll Road.) Everyone seemed surprisingly calm.

“It’s going about as well as an evacuation can,” said Thompson, who was operating on an hour of sleep. We climbed into his Chevy Tahoe and headed south toward the fire. Thompson is a big, middle-aged man with a Tom Selleck mustache and the unflappable manner you’d expect from someone who deals with disaster for a living. Though Las Conchas was the most impressive blaze he’d seen in his 20-year career, he told us, it wasn’t especially shocking to him.

Los Alamos had been scorched before. Back in May of 2000, firefighters lost control of a prescribed burn on federal land just south of town. The resulting Cerro Grande fire consumed 47,000 acres and destroyed some 300 homes and businesses. Thousands of firefighters from across the country fought it for more than a month, at a cost of $1 billion.

“I was having lunch in town when I saw the column from Las Conchas,” Thompson said, sounding resigned. “It was déjà vu all over again.”

THE LAS CONCHAS FIRE started at around 1:30 on a hot Sunday afternoon, apparently when gale-force winds knocked a large tree, perhaps just a limb, onto a power line near the Las Conchas trailhead, just south of the sweeping elk-filled grasslands and thick-timbered forests of the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The exact cause of the fire has not been made official, but Forest Service personnel mentioned their tree theory at a public meeting Tuesday night. Maps indicate that the mishap occurred on a utility easement cut through a large private property known as the Triple-H Ranch. (See the ; şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř’s attempts to reach the owners of the ranch have been unsuccessful.)

Within an hour, more than 100 acres had burned. Predicting that the situation would quickly get much worse, given the dry year New Mexico is having and with a separate, 10,000-acre blaze already raging north of Santa Fe, Robert Morales, incident commander for Santa Fe National Forest, called in a Type One Incident Management Team.

Type One teams are the elite, a hybrid logistical crew put together by cherry-picking the best administrators from federal agencies like the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Park Service. They deal with all kinds of natural disasters, not just fires, and in 2011 they’ve organized responses to everything from last spring’s midwestern tornado outbreak to Arizona’s gargantuan Wallow fire.

The fire was taking shape. From its ignition point, it blew west in the shape of a cone. When the winds shifted north, the cone’s northern point blew out, sending a strap of fire up the eastern edge of the Jemez Mountains. The whole thing began to look like an amoeba, slowly wrapping its way around Los Alamos.

The first team called to Las Conchas—there are two in place now—is led by the Forest Service’s Joe S. Reinarz, a stocky, gray-haired field general who immediately ordered more than 1,000 firefighters to begin making their way to Los Alamos, a process that can take days. In the meantime, 150 or so city, county, and federal firefighters were doing their best to arrest the blaze. The odds were stacked against them. Several 90-degree days and 20-mile-per-hour winds had whipped the flames into hard-to-reach canyons and up steep mountain slopes. There was little to do but warn homeowners to get out.

Two hours after the fire started, more than 1,000 acres had been blackened and the flames were racing east, toward Los Alamos, through thick stands of ponderosa, aspen, spruce, and juniper that line both sides of New Mexico’s State Road 4. It advanced by a process called long-range spotting: fist-sized embers from burning tree crowns were thrown by the wind as far as two miles ahead of the main blaze. Thanks to a drought that persisted in the Southwest through the winter and spring, the vegetation in the area was so dry that the embers could land, burst into flames, and consume gigantic trees in minutes. By the time the fire crested the Jemez Mountains’ east ridge, which rises to the west of Los Alamos, Las Conchas had destroyed 13 homes in a six-mile-wide swath of forest.

Then it really took off. Out on the eastern slope of the Jemez, 50-mile-per-hour winds sent the fire speeding downhill—a direction fires usually don’t like to go—toward LANL and its stockpiles of nuclear weapons and associated waste.

BY MONDAY THERE WAS widespread concern—as there had been during the Cerro Grande fire—that Las Conchas would roar into the highly restricted 27,500-acre mesa-top property that houses LANL. The national media were contacted by a small Santa Fe–based watchdog group called Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, which alerted them to a menacing place called Technical Area 54, inside the lab’s Area G section. Area G houses around 25,000 drums of plutonium-contaminated waste—rags, old hazmat suits—much of it kept beneath canvas tents pitched on blacktop.

Time magazine ran a story on its about the Lab’s nuclear safety, and Japanese-American physicist Michio Kaku, a frequent cable-news commentator during the Fukashima reactor meltdown, did interviews with local news stations. Kaku emphasized that the bulk of the radioactive materials had been secured, but he still had plenty of concerns. “What we’re worried about is what happens when the fires go right into buildings and perhaps pop open some of these 55-gallon drums,” he said. If that happened, would rise from the flames and be swept downwind toward Santa Fe. Since inhaling even one microscopic fleck of plutonium is likely to be fatal, the consequences could be cataclysmic.

The Area G threat was vastly overblown, though. The drums were about 3.5 miles from the fireline, in a rocky canyon with sparse vegetation. What’s more, any public-health fallout from this fire or from future outbreaks—and there is likely to be some—is apt to come as a result of waste we don’t know about, not from the stuff neatly stacked in barrels. Over the course of LANL’s 68-year history, regulations on what got dumped where weren’t always strict. There are 2,100 trenches, pits, and open-air vaults that contain—or once contained—dangerous waste. A by the New Mexico Environment Department, which identified many of these locations, concluded that solid waste at LANL “may present an imminent and substantial endangerment to health or the environment.”

Several of the sites are spread among the 18 canyons, each as much as 400 feet deep, that reach like fingers through and around Los Alamos and drain eastward into the south-flowing Rio Grande, ten miles from the lab. This April, clean-water advocates, concerned that runoff flushed contaminants into the state’s water supply, won a that will force the federal government to clean up many of these waste sites. As recently as 2009, $212 million dealing with hazardous waste around Los Alamos, and LANL director that even the lab itself doesn’t know precisely where all the waste is.

“Is our knowledge perfect?” McMillan said. “No. Is it zero? No.” The bottom line is: if you don’t want rain landing on it, you probably don’t want it to burn.

DURING OUR MONDAY-AFTERNOON tour, Thompson drove east on Highway 4 into the Valles Caldera, a federally managed preserve. On Sunday, he’d told us, his crews had assisted the Forest Service by lighting backfires—intentionally ignited controlled burns—off the south side of the road, just above LANL. Backfires are set to rob a wildfire of its fuel. If all goes according to plan, the whole thing fizzles. Things did go as planned Sunday night: Thompson and his crew held the fire at bay south of the road for a few hours. But on Monday, at around 11 a.m., the winds turned north and sent embers flying across the pavement.

The Las Conchas fire was off and running again, this time straight toward Los Alamos. Sometime around 1:45 p.m., just as Schaffer and I were preparing to leave for Los Alamos, flames crossed a contingency fireline near Pajarito Mountain, a small ski area five miles west of town. That was too close for comfort. Los Alamos police chief Wayne Torpy gave the order to evacuate.

While people scrambled to get out, Thompson drove us through the previous day’s burn. The air was thick and yellow with smoke, but the scene looked more like a thousand little campfires than the single wall of flame that had caused Sunday’s damage. Seeing the burn was less exciting than TV news footage would lead you to believe; many trees were still green inside the perimeter.

“It’s certainly a lot calmer out here than it was last night,” said Thompson. Even so, the forest was primed to go off. When he pulled over to let Schaffer film a hot spot on the south side of the road, the wind picked up. In an instant, an island of green inside a swath of blackened ponderosas was engulfed in 120-foot flames. The roar sounded like a freight train crossing a bridge. It was more like experiencing an aftershock than the earthquake itself, but it conveyed a sense of the incredibly powerful forces at work.

Thompson thought that if the Las Conchas fire was going to reach Los Alamos, it would get there on Monday night, when the wind was predicted to reach 20 miles per hour again. Additional firefighters from Reinarz’s team were beginning to arrive from across the Southwest, many of them veterans of Arizona’s 500,000-acre Wallow fire, the largest in the state’s history, which is still burning.

A handful of newly assembled crews were staged at St. Peter’s Dome Road, a dirt track off State Road 4, southwest of Los Alamos, that bisected the blaze from north to south. Most of the houses that burned on Sunday were in the communities of Las Conchas and Cochiti Mesa, near St. Peter’s Dome. Now the firefighters were hanging around, waiting in what they called their buggies—ten-seat Ford F-450’s or similar behemoths specially adapted to support smelly, hardworking men (and a few women) for up to three weeks at a stretch.

At this point, Thompson said, the fire had a real chance of reaching Los Alamos. “All it would take is a wind shift back to the east,” he explained. “If that happens, it will come over Pajarito.”

And, from there, right down the ski trails into town. Thompson was called back to the command center to help prepare the night shift. He dropped us back at the high school at 6 p.m. The smoke had already darkened the sky, and the town was empty except for National Guard Humvees and emergency vehicles, which drove past with their lights flashing.

BY THIS TIME, the fire had burned another 20,000 acres, upping the two-day total to 60,000. Higher humidity on Tuesday limited its spread to some 9,000 acres. But on Wednesday, the same southeast wind that led to Sunday’s breakout returned and blew in 45-mile-per-hour gusts toward Los Alamos. Firefighters managed to save the structures on Pajarito, but at least one ski lift’s chairs were sent tumbling to the ground after a cable snapped. Around 5 p.m., Reinarz pulled his men off the mountain to regroup.

To understand how firefighting on this scale works, it’s helpful to think in terms of what ·É´Ç˛Ô’t burn: dirt, rivers, paved roads, and already-blackened forests. The list of tools Reinarz has for creating or optimizing these barriers isn’t particularly long. Helicopters, like the nine committed to the Las Conchas fire, use 1,500-gallon buckets of water slung underneath to douse hot spots near the fire’s perimeter. Aircraft, including retrofitted C-130’s, drop loads of sticky red retardant ahead of a fire to saturate vegetation and slow its spread. Because of the high winds and steep terrain associated with the Las Conchas fire, the C-130’s were grounded and the helicopters were mostly used in the flatter parts of the blaze.

But 52 fire engines and their three-to-five-man crews were hard at work. Engines hold between 500 and 1,500 gallons of foam-laced water that can be used to knock down flames on the fire’s advancing edges. These temporary lines are then reinforced, either by bulldozers, when the terrain permits, or by 20-person hotshot crews who clear a fireline using chainsaws and hand tools. Once their work is complete, the hotshots use torches to light a burnout between the wildfire and the line.

This was the drill Monday night and all through Tuesday and Wednesday. By 5:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Reinarz was running out of options. Wind was pushing the fire directly toward Los Alamos and the lab, and the flames were too hot for engine crews to work. He decided to do a burn off Highway 501, which forms LANL’s western border. (On a , Highway 501 is along its southeastern flank.) By all accounts, the plan worked brilliantly. The burnout ran toward the wildfire, and the flames—at least near LANL—backed down.

On Wednesday, Los Alamos County fire chief Doug Tucker announced, “In my professional opinion, there is a less than 10 percent chance of spot fires on lab property this evening, diminishing tomorrow.”

For the time being, it seems unlikely that Las Conchas will burn LANL or Los Alamos. But the fire is only 3 percent contained. As of Friday, it had destroyed 103,842 acres, and fire managers were considering calling in a third Type One team. The fire is now burning tribal lands on the Santa Clara Pueblo—6,000 acres were singed Thursday alone—and is consuming thousands more in the direction of Pedernal Peak, the flat-topped mesa Georgia O’Keeffe made famous in her iconic paintings. Suppression costs have already exceeded $3 million. There’s no way of knowing how high that number will climb when the rains, the only thing that can extinguish a fire this big, finally come.

For now, the focus remains on slowing the advance. Later, we’ll debate whether things like increased logging or allowing natural fires to take their course could have prevented this. And, of course, there’s the issue of whether it’s really a good idea to house one of the country’s most sensitive nuclear-weapons facilities in the middle of a tinderbox. But all that can wait. The firefighters are doing an amazing job.

OF COURSE, SCHAFFER AND I knew none of this Monday evening as we prepared to head back to Santa Fe. We did know that we didn’t quite have the story we came for and that the fire was beginning to burn its way down Pajarito toward Los Alamos. We parked in view of Pajarito Mountain, waited for the winds to materialize, and called every fire contact we had to try and get a better look at the Battle for Pajarito.

At 9 p.m., a bored National Guardsmen tasked with keeping order in a town with only 150 stubborn residents who wouldn’t leave walked over to chat us up. Ten minutes later, he waved us through a roadblock. Schaffer and I were one parking lot closer to the action. Finally, at 11 p.m., unable to reach anybody who could put us on a crew, we decided to walk over to the firehouse and try a more direct approach.

“Any chance we can hop a ride to the fire?” I asked a volunteer firefighter.

“Can’t do it. The trucks are full,” he said. Then his supervisor saw us and called LANL’s security detail. Turns out the firehouse was actually on lab grounds, which means reporters with cameras asking questions—even about the fire—were strictly forbidden.

Two SUVs pulled up. Then two more, and four guards who looked like former Navy SEALs interrogated us. Schaffer did the talking. They took our names, looked us up in a secret government database—or, more likely, on Google—and then told us to get out of town. We didn’t argue.