The Massive Land Deal That Could Change the West Forever

Utah congressman Rob Bishop, a conservative Republican who has long opposed federal management of western lands, has emerged as the unlikely architect of a grand compromise, one that would involve massive horse trading to preserve millions of acres of wilderness while opening millions more to resource extraction. Is this a trick, or the best way to solve ancient disputes that too often go nowhere?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The American West is our handsome conundrum—too beautiful to use, too useful to be left alone, as a Colorado journalist once put it. In the past, the landscape seemed so enormous that conflicting dreams could find room in its whistling emptiness. Now there’s not much left that we haven’t touched, and we argue about how to manage what remains—a quarrel over whose dreams should come first.

Nowhere is the argument louder than in the creased country of eastern Utah, a place you know even if you’ve never been there: stone arch and sunburnt canyon, perfect desert sky. The area is home to marquee national parks like Arches and Canyonlands, but much more of it exists as sprawls of federal land that, taken together, are larger than many eastern states. Some people look at the region’s deep slots, peaks, and antelope flats and are inspired to protect them from development. Others hunger for what lies beneath: natural gas, oil, and potash.

If conservation is a tricky project in today’s rural West, with a resurgent Sagebrush Rebellion leading to events like the armed takeover of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon, it’s particularly confounding in Utah, where, for the better part of a century, a war over wilderness has been fought. Recently, during travels through small eastern Utah towns like Moab and Vernal and Blanding, I met more than one Utahan whose pioneer ancestors had arrived by wagon train and who still couldn’t bring themselves to utter the word “wilderness,” famously defined in the 1964 Wilderness Act as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Instead they called it “the W-word,” and they spat it out when they said it. In Utah more than other states, environmentalists and their foes wield just enough power to stymie each other. The toll has been great: enemies have grown gray squatting in the same trenches their fathers dug, and still the land remains unconquered by either side.

In early 2013, a conservative Utah congressman named Rob Bishop sent a letter to more than 20 groups in both camps of the wilderness wars. He said to them, simply: Tell me what you want. He proposed using their responses to frame an ambitious “grand bargain” designed to end the state’s wilderness disputes. In Bishop’s hoped-for compromise—officially known as the —everybody would get some of what they desired, as long as they were willing to negotiate. Conservationists could potentially protect the largest amount of wilderness acreage in a generation—a Vermont-size array of wildlands that would be free from development forever—including places whose names are talismanic to desert rats: Desolation Canyon, Indian Creek, Labyrinth Canyon. And the conservative counties of eastern Utah would get some assurances that more motorized recreation and future development would be allowed to happen on other public lands, along with the economic benefits those projects promise to deliver.

Late last fall, during a telephone interview from his offices on Capitol Hill, Congressman Bishop told me that he decided to pursue the grand bargain when he realized that the old conflict-based manner of tackling disputes had failed. “I’ve got to break paradigms and try something new,” he said. But why something so ambitious in a place so difficult? Bishop invoked a favorite quotation, one that he and others often attribute, perhaps apocryphally, to Dwight Eisenhower: “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.”

Eventually, any such plan will be introduced into Congress as a bill that spells out what’s being traded for what. And in theory, a grand bargain that has the support of all sides would stand a decent shot of navigating the hyper-partisan halls of Congress to become law.

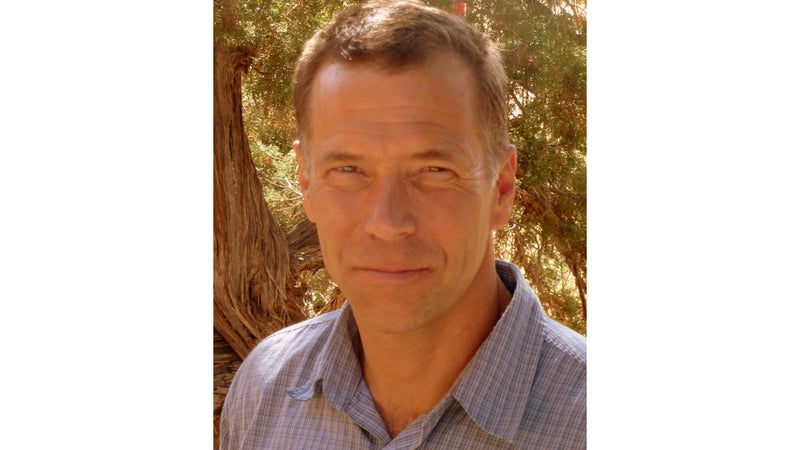

A few years ago, if you had asked which politician would emerge as the Great Compromiser on wilderness, Bishop wouldn’t have been anybody’s first choice. Now 64, he’s a seven-term congressman from Utah’s First Congressional District, which stretches across the top of the state. The federal government manages nearly two-thirds of Utah’s land, and Bishop firmly believes Uncle Sam is terrible at the job. He has likened federal ownership to Soviet collectivism, and he argues with a pungent eloquence—he’s a former high school debate coach—that the government should get out of the stewardship game and revert the land to local management.

“When you try to control the land from a four-, five-hour flight away, the people always screw up,” he told me. He has repeatedly fought to weaken environmental laws and neuter federal agencies like the Bureau of Land Management, the National Park Service, and the Forest Service.

Yet Bishop is no wild-eyed back-bencher. He’s chairman of the powerful , with sway over issues ranging from energy production to mining, fisheries, and wildlife across one-fifth of the nation’s landmass. Last fall he helped kill renewal of the 51-year-old Land and Water Conservation Fund—which raised billions for recreation and state and federal land acquisition, until it could be overhauled. (The fund was in mid-December, but for only three years.) The has given Bishop a 3 percent lifetime rating. Still, he can be a powerful ally, as his work on the grand bargain shows. Bishop’s effort is a genuine attempt to solve the kinds of long-stewing western land-use conflicts that, at their worst, devolve into potential violence.

Time is running short for Bishop, however. The Obama administration has given him room to cobble together a deal with conservationists, ranchers, Native Americans, energy companies, and others—the kind of huge, grassroots pact that most parties would prefer. But if an agreement isn’t reached soon, the president appears poised to step in and do some preservation of his own, in the form of a major new national monument in eastern Utah called the Bears Ears. The clock is ticking.

For some critics, though, the deal struggling to be born is a devil’s bargain. And it has exhumed a pressing version of an age-old question: How much can you compromise before you sacrifice the very thing you’re trying to save?

Last September, nearly three years after Bishop sent out his letter, I traveled to eastern Utah to check on the progress of his idea. Initially, Bishop had asked various groups—everyone from the Utah Farm Bureau to theNature Conservancy—to put their wish lists to paper within a month. In the years since, more than 1,000 meetings have been held, involving dozens of interested parties, as counties worked on detailed proposals to submit to the offices of Bishop and his congressional colleague, representative Jason Chaffetz, a Republican whose district includes southeastern Utah. Now everyone was waiting to see how the congressmen would merge these often conflicting dreams into one plan without pissing off everybody. Deadlines have come and gone. “It’s a total mess,” one staffer told me, referring to the difficulty of the process.

Still, it’s easy to see why several environmental groups are interested. Over the years, Utah’s deeply red political culture has often kept the state’s enviros on the defensive, simply trying to prevent losses. The , or SUWA, has filed so many lawsuits to stop development on state and federal land that its enemies call it “Sue-Ya.” From 1930 to 1980, more than half the lands in Utah that environmentalists would have called wilderness and are managed by the BLM—some 13 million acres—were lost to drilling, roads, and other development. Since 1980, however, greens have held the line. Less than 2 percent of would-be wilderness acres have been lost, thanks to efforts that have included land exchanges, lawsuits against oil and gas drilling, and other tactics, SUWA says.

“Utah has always been hard,” says James Morton Turner, author of , a history of modern wilderness politics. “It is the trail that wilderness has never been able to get to the end of. It is steep, straight uphill, hot and dusty.” Utah received no designated wilderness under the 1964 Wilderness Act; even today the state has fewer wilderness acres than Florida. The conflict over land and what to do with it has simmered for decades.

But Bishop’s idea strikes a chord with SUWA’s 58-year-old executive director, Scott Groene, who sees an opportunity to gain the kinds of permanent protections the group has long sought. A huge chunk of Utah—more than three million acres—exists in a limbo state known as wilderness study areas. These places are neither fish nor fowl; Congress has granted WSAs wilderness-like protections while they’re studied for permanent status. But some WSAs have been in a holding pattern for upwards of 35 years.

Groene believes that haggling to protect lands that already enjoy a degree of protection is “just a waste of our time.” Millions of additional acres of unguarded BLM lands are still out there, unprotected even by WSA status, according to environmentalists’ surveys. Greens also have their eyes on gaining wilderness protection for some Forest Service lands in eastern Utah. Traditionally, the Forest Service’s guiding principle has been embodied in the slogan Land of Many Uses, which means allowing everything from sheep grazing to timber harvests to mountain biking. Wilderness protection, by contrast, is the most stringent status available for federal lands. Motors and mountain bikes are prohibited; resource extraction is allowed only in cases involving preexisting mining claims and leases. Environmentalists have shown a willingness to be flexible, though, by considering less restrictive designations, such as national conservation areas, which block drilling but allow some other uses.

Still, the wish list is long. For example, above Moab, environmentalists want wilderness status for the forested La Sal Mountains that serve as the town’s watershed, now national forest. To the north, they want protection for the Book Cliffs, one of the largest nearly roadless places left in the lower 48. They also want protection for places of staggering beauty and lonesomeness such as Bowknot Bend, where the Green River coils back on itself at the bottom of a canyon of sun-fevered rock. In his most optimistic moments, Groene, a former “hippie lawyer” who now wears dad plaids, allows himself to dream of a day when his group could shut its doors, its mission all but accomplished.

But what would cause the other side to budge?

To look for an answer, I fly into Salt Lake City and drive due east, past the ski resorts of the Wasatch, until the land flattens and bleaches and oil jacks nod their equine heads. This is Uintah County. On the same day Bishop sent his first letter to groups like SUWA, he sent a second, different letter to the elected commissioners of Uintah and every other county in Utah—the level of government that, to Bishop, best serves the ideal of local control. Bishop acknowledged the long stalemate over their public acreage. Then he told the locals how to break it. Wilderness, he wrote, “can act as currency”—chips that can be cashed in, in exchange for projects like drilling pads, mines, and airports. “The more land we’re willing to designate as wilderness, the more we’re able to purchase with that currency.”

This was new, and it would change the way wilderness skeptics looked at the W-word. The counties of eastern Utah, which had been bloodied and economically frustrated by wilderness stalemates as much as any counties in the state, took notice.

In Congressman Bishop's grand bargain, conservationists could potentially protect the largest amount of wilderness acreage in a generation—a Vermont-size array of wildlands that would be free from development forever.

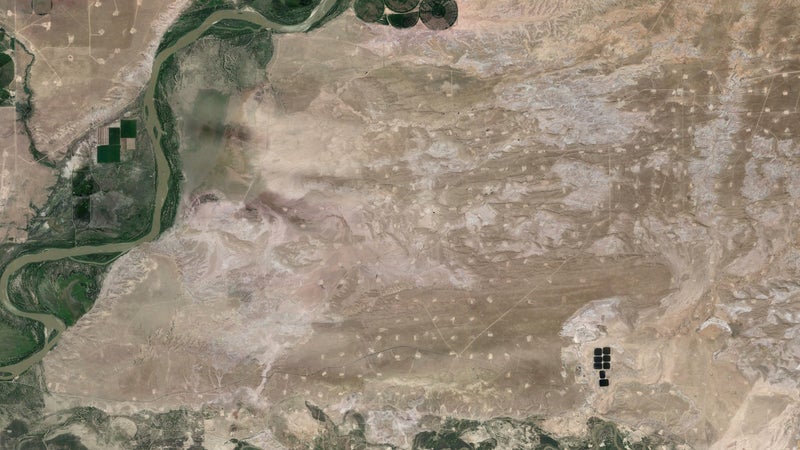

No place illustrates this better than Uintah County. Millions of years ago, the Uinta Basin was a vast, shallow inland sea. Today, beneath the ground, there’s an ocean of hydrocarbons that could make Uintah one of the next global hot spots for energy extraction. The county, which is nearly the size of Connecticut and covers much of the basin, already has more than 7,100 oil and gas wells—and a world-class pollution problem—but that’s nothing compared with what boosters hope for. The ground holds huge amounts of additional oil and natural gas, plus oil sands and oil shale. The energy isn’t found only in Uintah: in 2012, the most productive oil well in the lower 48 was located outside Moab, and as many as 128 more wells could appear in the area in the next 15 years, the BLM projects.

In Vernal, the Uintah seat, I speak with county commission chairman Mike McKee, an ex-farmer who explains the problem as he sees it. The feds own nearly 60 percent of his county, including many of those potential future oil lands, where would-be drillers are subjected to Washington’s bureaucratic red tape, the shifting energy policies of successive presidential administrations, and lawsuits, all of which can make drilling on federal lands more difficult and uncertain than drilling on state lands. If counties like Uintah compromise, officials want dependable assurance that companies really will be able to drill.

McKee stands before a rainbow-colored map in a conference room. It shows the new protections that Uintah County officials think they can stomach and what they want in return. The map is the outcome of dozens of meetings involving everyone from snowmobile groups to the Wilderness Society, McKee explains, and similar maps have been cobbled together all over eastern Utah. Up in one corner, there’s a new wilderness area in the Uinta Mountains. Another is marked in the south, for Desolation Canyon. (“Their ultimate prize,” McKee says of environmentalists. “A spectacular area.”) Negotiations are ongoing about the possibility of turning Dinosaur National Monument into a national park. And a blob of gray covers roughly half the map—a proposed new “energy zone,” where current or future oil or gas drilling or tar-sands operations could occur.

It might be hard to find enough common ground to facilitate any huge deals simply by swapping lands. But Utah has something else to grease the bargaining wheels. During the statehood processes that occurred when the West was settled, the federal government gave new states land, arranged in a checkerboard pattern, most of it to be logged, mined, or grazed, with the proceeds largely helping to fund state schools. In Utah today, these trust lands make up 6.5 percent of the entire state—millions of acres. But since they are still arranged in checkerboard patterns, many sit inside federal lands that are now wilderness study areas; they’re like holes in a doughnut. Critics, including Bishop, say this effectively makes the land undevelopable, leading to underfunded schools. (The real cause of that problem, many believe, has been Utah’s tax-averse citizenry.) However, these state lands can be legally mined and drilled, and the federal government has to allow access to them, even through potential wilderness. That’s why Groene calls them “a ticking bomb.”

Many on both sides would like to see them on the trading block. Environmentalists want the development threats removed. Counties and state legislators want the parcels traded out for other lands that are more accessible. Both sides have something to gain.

During the time I spend researching the grand bargain in Utah, many people tell me that what is unfolding might represent the future of land conservation in America. “This could be a model for other states to resolve these issues in a constructive way,” says Mike Matz, who directs wilderness conservation projects for the , one of the nation’s largest conservation groups. Utah’s collaboration has spurred counties in Wyoming to try to settle the future of hundreds of thousands of WSA acres there. Whether this trend should be applauded is hotly debated, however.

Land conservation in the U.S. is harder today than ever. The easiest places to protect—the high country of peaks, pines, and pikas—have already been taken care of. What generally remains are lower-elevation lands that have more claims on them, whether from off-road drivers, mountain bikers, or energy companies, according to Martin Nie, director of the at the University of Montana. Add a highly polarized Congress that won’t pass anything even remotely controversial and you’ve got a formula for inaction. “The market is dictating that tactics need to change,” says Alan Rowsome, the Wilderness Society’s senior government-relations director for wildlands designation.

Enter collaborative dealmaking. Collaborations have their roots in the watershed groups that formed in the late 1990s, during the Clinton administration. Collaboration often comes down to stakeholders—ranchers, loggers, ATV groups, environmentalists—sitting in a room and negotiating about lines on a map. The goal is to strike a balance between the needs of nature and the ever greater demands of people. Over the past 15 years, some of the nation’s largest and most respected environmental groups—including Pew, the Wilderness Society, and the Sierra Club—have played active roles in collaborations around the West. At its best, collaboration has helped break logjams in stubborn public-lands conflicts and has created a new way forward to protect significant chunks of the map.

But some environmental watchdogs, wilderness specialists, and academics worry that the approach is also setting dangerous precedents. In their pursuit of land preservation and wilderness, critics charge, environmental groups frequently horse-trade inappropriately with the public’s lands—shutting out dissent, undercutting their conservation mission, and even eroding bedrock environmental laws.

“Utah has always been hard,” says author James Morton Turner. “It is the trail that wilderness has never been able to get to the end of. It is steep, straight uphill, hot and dusty.”

Many say the new collaborative trend began in a remote place in eastern Oregon called Steens Mountain. In 2000, environmentalists and ranchers brokered a complex agreement that involved new wilderness and land exchanges, and also created a novel management area on public land that would be overseen in part by the ranchers themselves. Some environmentalists praised the compromises, but to Janine Blaeloch, founder and director of the watchdog , the deal smelled funny. Blaeloch was particularly concerned about how conservationists gained protections around Steens only if they “paid” for them with outright losses of other public lands or by agreeing to reduced protections elsewhere. Blaeloch dubbed it “quid pro quo wilderness.”

The trend soon gained popularity in Nevada, where four-fifths of the state is managed by the federal government. Having had success with a deal in Clark County, which surrounds fast-growing Las Vegas, Democratic senator Harry Reid tackled a more collaborative effort in a large county to the northeast, Lincoln. At first glance, the seemed like a success: it created 14 wilderness areas covering nearly 770,000 acres. The bill had the support of the Wilderness Society and the Nevada Wilderness Coalition, the latter supported financially by a Pew-backed group called the .

But a closer look revealed a disturbing deal. Nowhere did the Lincoln County bill break more with the past than by going against a long-standing government policy of trying to keep federal lands in federal hands. Instead, according to historian James Morton Turner, it required the feds to sell more than 103,000 acres of public land at auction.

Twenty years ago, when environmentalists haggled over protecting lands, they sometimes compromised in a way that temporarily returned hoped-for wilderness acres to the kitty while they continued fighting to protect them at some future date. In Nevada, the environmental groups hadn’t simply delayed protection for public lands; they allowed them to be sold off entirely.

Inspired by Lincoln County, other collaborative efforts followed, including a controversial 2008 deal across the state line in southwest Utah’s Washington County and another in the dry Owyhee country of southwest Idaho in 2009. And why not? “Collaboration” sounds great. It suggests consensus and compromise—the idea that everyone will be heard and their ideas made part of the finished product. But as George Nickas, executive director of , has said, compromise sometimes means “three wolves and a sheep talking about what’s for dinner.”

In short, whether collaboration is a good thing or not depends a lot on where you stand—and what you stand to gain. A 2013 study found that the groups most likely to collaborate are large, professional environmental organizations that often represent diverse agendas. According to Caitlin Burke, a forestry expert in North Carolina who has studied collaborations, if such trends continue, “we will see a marginalization of smaller, ideologically pure environmental groups [whose] values will not be included in decision making because they are unable or unwilling to collaborate.”

±ő»ĺ˛ąłó´Ç’s , for instance, which steers issues like ranching in southwest Idaho, has banned from participation groups that have successfully litigated to reduce grazing in areas of the Owyhee. The initiative, however, preserves a role for more mainstream groups like the Nature Conservancy and the Wilderness Society.

Despite appearances, collaborations are undemocratic, argue critics like Gary Macfarlane of , an environmental group in northern Idaho. The public already has a process for how changes can be made to our public lands, Macfarlane says: the . Macfarlane describes it as “a law that tells federal agencies to look before you leap” and says you have to allow all interested parties to participate. The act also mandates that the best available science be considered. Collaborations don’t have to do that, says Randi Spivak, director of the public-lands program for the .

Then there are the concerns about wilderness. Designation of new wilderness areas has often been a centerpiece of collaborations over the past 15 years. But in order to push wilderness through, the big environmental groups have been willing to make sometimes disturbing compromises, critics say—even to the Wilderness Act itself.

Compromise has long been a central part of wilderness politics, of course. The 1964 Wilderness Act took eight years and 65 bills to become law, and the final act grandfathered in some grazing and mining. But the old compromises were largely about boundaries—what’s in and what’s out. The new deals embrace a more insidious type of compromise, not just about where wilderness will be, but also about how it will be managed.

“Our fear is that some conservation groups look at the 1964 act as the place to begin a new round of compromises,” says Martin Nie. That shift, he adds, “could threaten the integrity of the system.”

In collaborative efforts, large conservation groups that badly want to protect wilderness must deal with groups that sometimes loathe the idea, so conservationists increasingly feel pressure to make wilderness more palatable to opponents—and that means watering it down, says critic Chris Barns, a longtime wilderness expert who recently retired from the BLM.

The number of special provisions—exceptions added to a wilderness bill, almost always leading to more human impact—has increased in the past several years, in the International Journal of Wilderness. The Lincoln County deal was saddled with a raft of such provisions. The Owyhee deal, given a thumbs-up by such groups as Pew and the Wilderness Society, lets ranchers corral cattle using motorized vehicles, which is supposed to be forbidden in wilderness. The result of such compromises, Barns and others say, are areas known as WINOs—”wilderness in name only.”

Another problem with these exceptions is that they become boilerplate for future bills, Barns says. A provision that first appeared in 1980 has since turned up in more than two dozen wilderness laws. Such changes might seem small, says Barns, but they erode, bit by bit, America’s last wild places.

The large environmental groups involved in these deals say such criticisms are off base. “For us, what it comes down to is, as the nation grows, there are less and less wild places left in America,” says Alan Rowsome of the Wilderness Society. “And we want to protect them as soon as possible, because if you wait ten years or fifteen years or twenty years, that place may not be protectable. It may not be as wild a place, or as open, or as important to protect.”

As for the criticisms about horse trading, Pew’s Mike Matz says, “I would submit that these deals have always been complex. At the end of the day, we are entirely comfortable with the deals we have struck.”

But Athan Manuel, lead lobbyist for the Sierra Club on federal-lands issues, acknowledges some of the criticisms. “We don’t have to get some of these bad deals just because we think the atmosphere is going to be worse next year,” Manuel says. “I think we sometimes suffer a crisis of confidence in the environmental community.”

Which brings us back to Utah and the grand bargain. With Pew and the Wilderness Society heavily involved throughout much of the process, critics were watching and worrying. Though Bishop hadn’t yet unveiled his final proposal, some didn’t like what they were hearing—that green groups were willing to swap out Utah’s school trust lands for parcels located elsewhere, so that wildlands could be consolidated and the state could more easily drill for oil and gas. “It’s wilderness for warming,” Randi Spivak says. “We should be keeping fossil fuels in the ground.”

“It’s painful,” SUWA’s Groene acknowledges, “because everything you give to Utah you have to assume will be sacrificed.” But the kinds of ethical dilemmas that collaborations have posed elsewhere? He’s still waiting on them. “The whole goal was to be put in that terrible place where we had to decide” those kind of things, he says. But they aren’t even there yet.

When I asked people for a place that exemplified the challenges and promise of the grand bargain, many pointed to San Juan County, which anchors Utah’s bottom-right corner. Though larger than New Jersey, it has only 15,000 residents, many of them conservative sons of Mormon pioneers.

The current county-commission chairman there is a man named Phil Lyman, who for the past three years has spearheaded the county’s public-lands advisory council, a citizens group that is charged with helping officials craft a proposal to give to Bishop. In the midst of that work, Lyman was convicted of leading an illegal ATV excursion into Recapture Canyon, an area that had been partly closed to protect ancient Native American ruins.

Lyman lives in Blanding—at 3,600 people, the county’s largest town—which was founded by his great-grandfather in the 1890s. It has a bowling alley, a bank, and a few wide streets that seem designed to take tourists elsewhere. On Main Street, old ranchers limp in and out of the San Juan Pharmacy. Down the block, I find the door to Lyman’s accounting office open. A sign inside invites visitors to take a complimentary copy of the Book of Mormon.

To environmentalists, Lyman, 51, symbolizes all that is backward in Utah. To others, he’s a hero for resisting government overreach. The day I meet him, he’s still waiting to find out if he’ll go to prison over his conviction for conspiracy and trespassing. (He was already fined and in mid-December would be sentenced to ten days in jail.) He scratches his head at the furor he has caused. It was all a misunderstanding, he claims.

“I’m the poster child for gun totin’, beer drinkin’, ATV drivin’, ” he says. “I’m an accountant!” He doesn’t even own an ATV. “But I do have a fire in the belly about hurting innocent people,” he says.

We drive into the sagebrush desert in Lyman’s pickup, and he tells the same story I’ve heard elsewhere about how reluctant he was at first for his county to join the grand bargain. All it would do is stir up trouble for years, with no resolution—and the county was already trying to start talks with a Navajo group. But once he decided to get on board, swayed by his elected duty to give the approach a try, Lyman threw himself into it.

To everyone’s surprise, people with different viewpoints actually started talking to each other, Lyman says. Around eastern Utah, cooperation was in the air. The Wilderness Society joined the grand bargain early on. So did Pew, though it generally pursued its own track. In the spirit of mediation, greens told Bishop that in some places they would be willing to accept less proscriptive national conservation areas instead of a stricter wilderness designation, which many counties feared.

Working county by county, the collaborators —a single puzzle piece in the larger grand bargain—in the fall of 2014 in Daggett County, a smaller county in northeastern Utah. (Individual deals like this, the hope went, would eventually be submitted to Congress as one overarching Utah lands bill.) Among other things, the agreement designated over 100,000 acres of wilderness and conservation areas in exchange for the acquisition of a large natural-gas facility and future development of a ski area.

Momentum was building. Summit County, home to Park City, asked to contribute to the Public Lands Initiative. An election in Grand County, home to Moab, saw ultraconservative commissioners voted out and a more receptive slate voted in. At various times, as many as eight counties across eastern Utah were in play.

The Bears Ears Coalition was formally withdrawing from the Public Lands Initiative and throwing all its efforts at lobbying President Obama for a national monument, citing missed deadlines, delays, and “no substantive engagement” with its concerns.

But just as the grand bargain looked most promising, the wheels started to come off. One month after Daggett County inked its deal, elections swept very conservative candidates back into power there. The new county commission reneged on the agreement that had just been celebrated. As Groene sees it, Bishop had made a crucial error by telling county officials that they had the power to stop any negotiation if they didn’t like how it was going. If you’re a small-town politician in rural Utah and you strike a deal that makes a lot of concessions to environmentalists, he says, “then all the people you know are going to yell at you in the grocery store the rest of your life. Politically, they can’t play that role in these small towns.”

When Daggett County reneged, Bishop didn’t seem to have a Plan B to keep momentum going elsewhere, Groene says. Bishop calls this criticism “terribly unfair.” After all, he says, “anyone can walk away” from this process—even the environmental groups.

Last summer, Lyman’s San Juan County was the last of seven counties to hand in its blueprint to Bishop. It called for 945,000 acres of protection, a mix of wilderness and national conservation areas. Parts of famous geologic landmarks such as Cedar Mesa, Comb Ridge, and Indian Creek, with its world-class rock climbing, would get bolstered protection. It was far more than many people expected—or that many others could tolerate.

“No one would have predicted that San Juan County would’ve come up with a proposal that included a million acres of land protection, and part of that protection uses the W-word,” says Josh Ewing, director of the group .

Yet the proposal still needs a lot of work, conservationists say. For one thing, the county’s plan (along with several others’) contains language inoculating it from the Antiquities Act. This law gives the president the power to preserve landscapes by creating national monuments on federal land without requesting local input or consulting Congress. Because San Juan County and other eastern Utah counties are more than 60 percent owned by the feds, many state politicians hate the act, calling it the epitome of government overreach. While the county sees the exemption as insurance that its hard work won’t result in a monument, conservationists consider an exemption a deal breaker.

Then there’s the Native American issue. About half of San Juan County’s residents are Native Americans, and about one-quarter of the county is reservation land. Because of a general lack of outreach, but also by their own choosing, only a few Native Americans participated in the county’s grand-bargain planning. “It’s a trust thing,” Lyman acknowledges. “I don’t blame any Navajo personally who doesn’t trust the white community, the federal community, the county.”

Lyman drives up Highway 95, the road where Seldom Seen Smith yanks survey stakes in Edward Abbey’s 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, and turns onto a dirt road. He stops the truck among Mormon tea and sagebrush, where the earth is slowly reclaiming the ruin of an old uranium mill. Bones of rebar poke through concrete. Lyman tells me that his grandfather once owned the nearby uranium mine, one of the richest around.

Conservationists want protection here. But under the county’s proposal, this would be an energy zone. Right now, Lyman says, there isn’t a mine operating anywhere from Durango to Hanksville. “Let’s really draw the line,” he says. “West of here would be the wilderness they want, and east of here would be the really productive public lands, managed intelligently. Real people, good jobs, putting food on the table.”

He toes a loose bit of concrete and squints into the hammered brightness of a desert noon. “When you’re from here, and your ancestors were part of this,” he says, grabbing his chest, “you ask yourself, What am I doing? What’s our legacy? Do we have anything to leave and show we were effective?”

Is this place God’s cathedral or man’s quarry? I’m reminded that how you answer depends on where you stand and where your grandfather stood before you.

On my other morning in San Juan County, I head out with Josh Ewing to see an alternate future for this place. After a 90-minute bounce over rough roads, Ewing stops his truck and disappears among old-growth juniper. I jog after him. We’re atop Cedar Mesa, a massive high plateau whose edges are fissured with canyons and that once was the northwestern frontier of a prehistoric civilization, home to the ancestors of today’s Hopi, Zuni, and others. Ewing—bespectacled, fast talking, a climber who fell hard for the red-rock country and is now director of Friends of Cedar Mesa—hustles through the sage and sand. “It gets in your bones,” he says as we walk past yucca and prickly pear, ripe with purple fruit. “It’s got that beauty combined with the archaeology.”

The junipers part, and the earth yawns open in a canyon of tall sandstone walls striped like candy. High on one wall perch several ancient cliff dwellings. We follow steps hacked into the stone that lead to ledges—the ground falling away 500 feet—until we reach walls, stone rooms, a granary. In the dimness of a kiva, or ceremonial room, a half-dozen gnawed corncobs stand upright as if in an artist’s still-life. Ewing guesses the place is 800 years old.

Ewing shakes his head: this side canyon and its relics aren’t protected in the plan San Juan County submitted to Bishop, he says, and they won’t survive another millennium without help. “Things don’t stay the way they are by not doing anything,” he says. Here was that difference again: while -Lyman wanted to leave a legacy by developing the land, Ewing and other conservationists wanted to do so by protecting it. His group estimates that there are more than 100,000 archaeological sites in the greater Cedar Mesa area—cliff dwellings, burial sites, kivas, petroglyphs, and pictographs. “There are probably closer to a quarter-million.”

I tell Ewing how, all that week in places like Moab, environmentalists said that the grand bargain was already on life support. The counties’ proposals were totally unrealistic, they said. Even Pew recently stepped back from talks, saying it couldn’t abide an Antiquities Act exemption. Ewing is more optimistic.

“I don’t think a legitimate negotiation has started yet,” he says. Only after Bishop unveils his draft proposal, he predicts, will the real, painful trade-offs happen. Why would he force his conservative constituents off their positions any sooner?

And if that movement doesn’t happen? I ask Ewing.

Then this play is over, he replies, at least as far as the legislative effort is concerned.

At the cliff’s edge, we talk about the possibility of a Plan B. For years conservationists have been working two tracks, also prodding President Obama to declare a massive national monument in eastern Utah before he leaves office. The prospect infuriates many rural Utahans, who still feel stung by Bill Clinton’s creation of in 1996. The pressure has given an urgency to the process.

Ewing sweeps an arm before us to introduce the leading monument candidate: the Bears Ears, a 1.9-million-acre triangle of land that would encompass all of Cedar Mesa, including more than 40 mini Grand Canyon systems that few people ever visit. (The name comes from the twin rock towers that rise over the landscape.) Twenty-five Native American tribes, some of them historic enemies, have united to .

As SUWA’s Groene sees it, the old battle lines are being drawn again, pitting cowboys against Native Americans and environmental groups. On one side are the counties, supporting a flawed grand bargain. On the other, tribes and greens pushing a monument that county officials hate. This time, however, the Great White Father in Washington, D.C., is black. He has declared or expanded more national monuments than any previous president and, sources tell me, is ready to give an underserved people what they want. (The White House did not respond to requests for comment.)

The night before I leave San Juan County, I have dinner in the village of Bluff with Mark Maryboy, the first Navajo to serve as a county commissioner there. Maryboy is as tall and lean as a piece of jerky, and he wears the pointed boots of a former rodeo bronc rider. I ask him why the Bears Ears is so important to Native Americans.

Maryboy doesn’t answer directly. Instead he tells stories. He says his grandparents used to live on Cedar Mesa. He says the Navajo have stories about everything—about the horned toads on the mesa, about how the sun is called Grandpa, about the male and female winds that live just north of the Bears Ears, and how, when a person has a breathing problem, he will seek out the right one to heal it. There are hundreds of stories, he says.

Only after I leave him do I understand what he meant. He wasn’t talking about acres. He was talking about a way to live.

On January 20, Bishop and Chaffetz . It would give added protections to about 4.3 million acres of Utah, roughly split among 41 new wilderness areas and 14 national conservation areas, as well as seven “special management areas.” To try to address Native Americans’ concerns, the proposal would create a nearly 1.2-million-acre conservation area for the Bears Ears, to be managed by federal agencies and advised by a commission containing some native people. It would expand Arches National Park and add more than 300 miles of wild and scenic river protection.

On the other side of the ledger, the proposal would release nearly 81,000 acres of WSAs, meaning that they could no longer be considered for wilderness status. It would create large zones for energy development. It would hand over some 40,000 acres of federal land to state and local governments. And it would give Utah right of way to a large majority of those contested 36,000 miles of dirt tracks that spiderweb eastern Utah’s canyon country, often on federal land—clearing the way for the state to open them to off-road -vehicles, or improve them, or even pave them, despite the wishes of Uncle Sam. As for the Antiquities Act—that part, curiously, was not addressed, so the counties will be able to suggest their own wording. The final bill “must include language that guarantees long-term land use certainty,” Bishop’s office wrote in a summary of the proposal.

Everyone was destined to be unhappy with aspects of the draft, Lynn Jackson, a Grand County commissioner, tells me, adding: “This is what compromise looks like.”

It may also be what failure to achieve compromise looks like, because reviews by environmentalist were rapid and negative.

To the eyes of SUWA’s Groene, the deal would give the farm to counties, off-road users, energy companies, and the state of Utah in exchange for little sacrifice on their part. “Those are swell-sounding numbers,” he says of the wilderness acreage, “but this whole thing falls like a house of cards when you look at what those numbers mean on the ground.” Several of the new wilderness areas, for instance, would lie within existing national parks, where the lands already enjoy significant protections. Taken together, Groene says, the proposal “actually means less protection than currently exists, advancing the state of Utah’s quest to seize our public lands and igniting a carbon bomb.”

So what now? Everyone will demand changes. The congressmen will take those demands and reemerge with a final proposal. “My name is on it,” Bishop told me last fall. “I’m not playing games with it. I’m not putting in stuff that I’d be willing to barter later.” The timeline for all this? Bishop seemed eager to keep things moving. He was clearly exasperated with the grinding process.

But environmentalists are no longer in the mood to play ball. “The bill is unacceptable and unsalvageable,” Groene says. “If they’d be willing to have a do-over, we would be willing to have discussions.” In San Juan County, Groene’s group won’t negotiate at all—they want the Bears Ears National Monument.

Another significant defection happened three weeks before Bishop’s draft appeared, when the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition announced that it was formally withdrawing from the Public Lands Initiative and throwing all its efforts into lobbying Obama for a national monument, citing months of missed deadlines, delays, and “no substantive engagement” with its concerns. “We don’t feel we can wait any longer,” the group said.

Weeks earlier, before all this, I asked Bishop if he was still optimistic about his grand bargain. “If it’s an even-numbered day, I feel positive,” he quipped. The Obama administration had been encouraging, he said. “They have never given me a deadline for anything per se.”

It was hopeful for Bishop to think that after so much work, the proverbial win-win was still within reach. Now that seemed more unlikely than ever. The Native Americans had been alienated. And despite Bishop’s assurances, time was running short to push anything through Congress during an election year, even with the support of powerful Utah senator Orrin Hatch.

The only certainty was that even the players on this stage didn’t know what was coming next—whether it was the end of Utah’s wilderness wars or just the close of yet another dyspeptic chapter.

“Make sure you’ve got popcorn,” said Casey Snider, Bishop’s legislative director. “It’s going to be quite a show.”

Christopher Solomon () is an şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř contributing editor.