Why Was a 26-Year-Old Computer Whiz from Ohio the Last Man Standing at Malheur?

The final holdout at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge occupation earlier this year wasn't a dyed-in-the-wool rancher or hardened militiaman. He was a young, half-Japanese kid from the Midwest who had no affiliation with the Bundy brothers or the Patriot movement. This is why David Fry drove across the country to join a group of extremists he'd never met.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

When the time came for David Fry to come out with his hands up, he huddled inside a tent of blue and white tarps and flicked a lighter at an unlit cigarette. He held a cellphone at his ear. On the other end, thousands of people listened.

âOK, David,â said a voice on a bullhorn outside the tent.

Fry paused and inhaled, then screamed out into the clear morning cold, âUnless my grievances are heard, I will not come out!â

șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍű, federal agents had surrounded him 15 hours before. It was February 11, just before 10:40 a.m. There were armored vehicles, agents in flak jackets, negotiators. A state representative arrived, pleading with Fry to come out. An evangelical preacher, too. A nearby roadblock stopped reporters and television cameras from getting any closer to the shoddy camp, situated on the frosted western edge of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, in southeastern Oregon, where Fry now sat alone. For 41 days, the middle-of-nowhere 187,000-acre bird refuge had been controlled by a group of armed men and women who believe that, according to the Constitution, public land belongs not to the federal government but to the people who live there. And they wouldnât leave until it was given back.

âI have to stand my ground. Itâs liberty or death,â Fry said into his phone.

Beyond the armored cars, beyond the roadblock, across the country and around the world, people tuned in to a livestream of the occupation on YouTube. Supporters running the stream hoped to capture and broadcast every gust of wind at the refuge, every crinkle of a tent, every voice, andâif it came to itâevery bullet fired.

More than 2,000 miles away, in an Ohio suburb, Fryâs father, Bill, tuned in to hear his son square off with federal agents. He turned up the volume on his speakers in the cluttered computer room of the family home. When the livestream began the night before, it was too much for his wife, Sachiyo. As federal agents closed in, the last remaining occupiers screamed at them to leave, cried to the livestream that they would die here, and taunted FBI agents, yelling, âKill us and get it over with!â Sachiyo ran upstairs to bed, unable to bear the thought that she might, at any second, hear her son be killed.

Since Fryâs arrival a month earlier, Bill and Sachiyo had called their son every day. On the phone, he sounded excitedâoptimistic about shedding light on government overreach. But Davidâs voice had taken a different tone after Robert âLaVoyâ Finicum, a 54-year-old Arizona rancher and leader at the occupation, was shot and killed after a highly publicized police chase. Fryâs optimism had been replaced with fear.

âIâm a free man. I will die a free man.â

Two weeks after arriving, Fry moved outside of the refuge office buildings, where he had slept on the floor between a file cabinet and desk, and into a tent made of tarps draped over car hoods and weighed down with spare tires. The muddy floor was littered with empty beer cans, water bottles, and camping-sized propane tanks. Fry slept there with three people heâd only recently met: a soft-spoken carpenter named Jeff Banta from Elko, Nevada, and Idahoans Sean and Sandy Anderson, a sort of camouflage-clad Boris and Natasha with Midwestern accents. International headlines dubbed them âthe final fourââthe last ones standing after a month-long coup dreamed up by a core group of extremists theyâd never even met.

Now those people were long gone. In late January, the majority escaped, speeding away from the refuge, leaving everythingâguns, ammunition, clothingâbehind. But by mid-February, 12 had been arrested and now sat in jail staring down federal conspiracy charges.

As the world listened on the morning of February 11, Banta walked out with his hands up. Then, just a few moments later, the Andersons surrendered, hands clasped together around an American flag over their heads as they left the refuge.

By 10:45 a.m., only Fry remained.

He was an unlikely holdout: a 27-year-old, rail-thin, long-haired, half-Japanese computer whiz who left his cozy upstairs bedroom in his parentsâ house in Blanchester, Ohio, and drove a beat-up 1988 silver Lincoln Town Car across seven states in the dead of winter to join the ranks of cowboys, militiamen, ranchers, anti-Muslim activists, sovereign citizens, and veterans staging what some hoped would become a violent standoff with federal officers.

Against the pleas of people on the phone, against the goading of an FBI negotiator, just after 11:30 a.m., Fry lay down on his sleeping bag and put a gun to his head.

âIâm a free man,â he said. âI will die a free man.â

Across the country, Bill Fry listened carefully.

The armed occupationâor armed protest, depending on whom you askâof the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge began atop a snowbank in Burns, Oregon, a half-hour drive from the refuge. On January 2, in a Safeway parking lot, a 40-year-old man in a cowboy hat and a blue flannel coat named Ammon Bundy climbed to the top of a pile of old snow and announced to a crowd that it was time to take a âhard standâ against the federal government.

Bundled in winter jackets and gloves, carrying âDonât Tread on Meâ flags, the 300 men, women, and children present had gathered to protest the impending prison sentences of two local ranchers, Dwight and Steven Hammond, convicted of arson after setting fire to land in Oregon owned by the Bureau of Land Management. It wasnât the first time a Bundy had sowed discontent among ranchers in the West. In 2014, Bundyâs father, Cliven, played host to militiamen from around the country who had congregated at his Nevada ranch to keep BLM officers from seizing his cattle. Cliven hadnât paid federal grazing fees in 20 years.

Just days before the Hammonds were to be sent to jail, Ammon Bundy proposed that the protesters take their grievances to the next level. âIâm asking you to follow me and go to the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge,â his snowbank pulpit. It was a strange venue for such a demonstration. President Theodore Roosevelt established the high-desert refuge in 1908 as a sanctuary for bird populations being decimated by plume hunters serving the hat industry. But in Ammon Bundyâs mind, the governmentâs grasp on the vast parcel had unfairly kept ranchers off the land. Hours after protestors descended upon the refuge, Bundy and promised that the protest would continue until the ranchers were pardoned and the government placed the refuge lands back in control of âthe people.â

âHe wanted to go somewhere where the world was listening.â

For the next few weeks, the mostly male group dug in. Protestors pawed through refuge files, copied documents, and rifled through boxes of Burns Paiute tribal artifacts. They clawed the land with backhoes, digging trenches they . They . They practiced target shooting. They prayed. They came and went from the refuge without interference from local law enforcement and FBI agents, who had set up a temporary command center at a nearby airport. At daily media interviews, the occupiers identified themselves as Patriots.

The Patriot movement shares space at the far right, alongside militias, sovereign citizens (people who donât acknowledge any federal authority), tax protesters, white supremacists, and single-issue extremists who, for example, refute federal-land ownership. Violent insurrection is a key tenet of the patriot movement, according to J.J. MacNab, an author and extremism expert at the . Patriot groups swelled in numbers after 1992, when an 11-day standoff in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, culminated in the wife and child of an off-the-grid Aryan Nations sympathizer being shot and killed. Even more people aligned with the movement in 1993, when an FBI standoff at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, ended in the death of 76 people.

Before the web, the Patriot movement depended on person-to-person recruitmentâvia pamphlets, leaflets, and fliersâand was relatively slow to grow. But today, âthe Internet and, in particular, social media, has usurped most of thatâ style of enlistment, says Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League, an organization formed to fight âall forms of bigotry.â The ability to spread propaganda instantly has been an effective tool for extremist groups like ISIS, which has recruited potential jihadists through social media and even dating sites. âItâs inevitably going to find its way into the hands and eyeball sockets of people who [are] receptive to it,â Pitcavage says. The numbers prove it: in 2008, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) knew of 149 Patriot groups nationwide; by 2015, there were nearly 1,000.

During the 2014 Nevada standoff, the Bundy family to call in fellow Patriots, ranchers, and militias from around the country. BLM agents tasked with rounding up Bundyâs cattle were met by dozens of armed men. Protesters livestreamed the scene. After three weeks of altercations, the BLM backed down and returned the Bundy cows. The incident was viewed as a Patriot victory, says Mark Potok, an expert on extremism with the SPLC. âLike Waco, it played to the idea of this massive tyrannical federal bureaucracy coming to wipe out the liberties of the small man,â he says.

It also exalted the Bundys âas the great defenders of the American people,â Potok says. Suddenly, the Bundy Ranch Facebook page became a virtual meeting place and de facto news site, connecting across borders and disseminating information for its cause. It exposed people who would have never gone to a meeting or a rally to the movement and the message.

So, on New Yearâs Eve, in 2015, when Ammon Bundy posted to Facebook, âALL PATRIOTS ITS TIME TO STAND UP NOT STAND DOWN!!!ââcalling people to Burns, Oregonâthe call was broadcast to computers across the country. One of them belonged to David Fry. Weeks later, he walked down the stairs, told his parents he was leaving, got into his Lincoln, and drove west.

âBefore you know it,â Pitcavage says, âDavid Fry is livestreaming from the compound.â

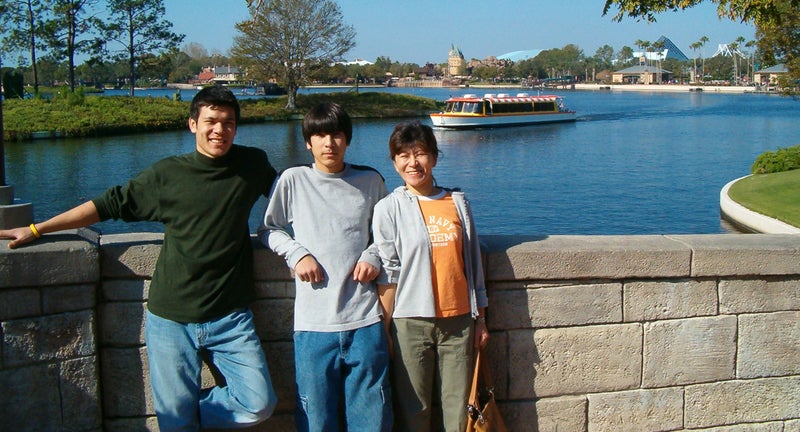

Bill Fry says a fighting spirit runs in his familyâs bloodline. His forbears fought in the American Revolution alongside George Washington at Valley Forge, then in the Civil War, and again in World War I. Bill Fry served in the Marines for 20 years, and now so does his oldest son, Daniel. His wife, Sachiyo, raised in Japan, says her ancestors were some of the last of the samurai class.

When the Frys had children, in the 1980s, they named their sons for their heroes. Their eldest son, Daniel, was named for the man angels saved because of his loyalty to God and for the patriot Daniel Boone. In 1988, while stationed in Yuma, Arizona, Bill named his next child David, for the biblical hero who bested a giant, and for Davy Crockett, the American frontiersman and sass-mouthed politician famous for telling his constituents they could âall go to hell.â

Davidâs first language was Japanese; he learned English at age three, when he took classes on the military base in Iwakuni, Japan. When David was in elementary school, the Frys moved back to the U.S., eventually settling in a rural suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio. Blanchester, the nearest town to the Fryâs home, is a predominantly white hamlet of 4,200 residents in the heart of the Rust Belt, an area hard hit when companies like Avon and Chiquita Banana shifted factory jobs overseas.

As two of just a handful of mixed-race students at his school, the Fry boys experienced frequent racism. âThey had problems with the local kids,â Bill says. Especially David. âThey referred to him as Hong Kong boy.â Middle school wasnât easier. By the time he entered Little Miami High School, in Morrow, Ohio, David was showing signs of depression, Bill says. But the family didnât consider treating him for mental-health issues until years later. âIâm not looking at him from a mental perspective in those situations,â Bill says. âIâm looking at him as his dad. My heartâs aching. Iâm just trying to get him some relief.â

âHe needs medical help, and instead he gets put in jail.”

At home, David was gentleâan animal lover who treated the family dogs and rabbits like siblings. He didnât like guns or huntingâa family pastime. Instead, he found solace in computers. He built custom gaming rigs and acted as the familyâs IT specialist. By 11th grade, he passed an entrance exam allowing him to start college courses at the nearby University of Cincinnati satellite campus, foregoing the need to subject himself to further school bullying.

Just when it seemed relief was in sight, David began getting into trouble with the law. Before graduation, police caught him smoking pot in a parked car with a friend and issued him a citation that carried hefty fines. In 2008, when David was 19, his parents became concerned about his mental health. âHe had a distant stare,â Bill recalls. His son was turning inward, spending hours online obsessing about anti-abortion causes and looking at grisly pictures of aborted children. David asked his father about government tests on U.S. citizensâthe Tuskegee syphilis experiment and LSD mind-control programs run by the CIA. âWhen you got some young kid asking, âHow can the government do that?â,â Bill told David he didnât have an answer. The Frys took David to a mental-health facility, where he was assessed and placed under a 72-hour watch. David escaped but was apprehended and arrested. âHe needs medical help, and instead he gets put in jail,â Bill says.

It seemed like it might be a wake-up call for David. He was transferred from jail back to the mental-health facility, where he spent five days and seemed to snap out of it. âI think possibly it was getting off the dang Internetâ that helped, Bill says. But it didnât last. Over the next year, David dropped out of college and moved home, taking a job fixing computers and sterilizing instruments in the familyâs dental office in Batavia. His best friend and his brother both joined the Marines. At home, David became heavily involved in World of Tanks, an online game in which he drove an imaginary tank into battle. He grew his black hair long, securing it in a ponytail. His humor became more abrasive.

Davidâs anti-establishment attitude crystallized in 2012, when he was caught smoking marijuana while rafting a nearby river without a life jacket. He was fined, given mandatory community service, and prohibited from driving. Bill says David was furious, feeling he was being bullied again. Davidâs run-ins with the law âshaped some of his opinions of how things are run in this country,â Bill says, and led David to believe that âthereâs a lot of corruption.â Three years later, in January, 2015, David got into an altercation with a police officer during a traffic stop. According to the arrest report, he was âbelligerent, moving wildly in [his] vehicle unable to sit still.â Then, while trying to get out of his car, David engaged in a pushing and shoving match with the door before the officer ordered him out of the car and onto the ground, threatening to taze him if he didnât put his hands behind his back. Once inside the police cruiser, Fry banged on the separation barrier, swearing and yelling, and called the officer a Nazi before making suicidal remarks.

Bill Fry still canât wrap his head around how his son could accrue so many legal issues. âInitially I told him, âDavid, it must be something you did,ââ he said. âHow could he get so unluckyâŠAfter the second time, third time, fourth time, Iâm like, âSon of a bitch, the justice system is a little screwed up here.ââ

On September 7, 2015, David Fry found an online community of people who shared his distrust of the federal government. A YouTube channel called âOne Cowboyâs Stand for Freedomâ featured a smooth-faced, even-tempered 54-year-old Mormon rancher from Arizona named Robert âLaVoyâ Finicum. The man had participated in the Bundy Ranch standoff in 2014 and had recently authored a book of postapocalyptic fiction, titled Only by Blood and Suffering, about a cowboy trying to survive under a tyrannical government. In one video, Finicum discusses his refusal to pay to the BLM for grazing fees. Fry commented on the video, sharing his own refusal to pay the government.

âI refuse to pay my tickets for not wearing a life jacket in a 3 foot deep river and smoking marijuana!!â he wrote. âFuck you government! They sent me to collections LMAO!!âŠFuck your taxes! Fuck your fines!! Ain't getting money from me!â

Finicum replied, âThanks for your support David.â

Fry was eager for attention: âNo, sir. thank YOU! you give people like me hope. I really mean that. Yah bless you! Halleui Yah!â

In Fry, Finicum had found an enthusiastic fan. âShare and spread the word, there is power in numbers, it will take each one of us to save this Country and the Constitution,â he wrote.

Fry responded, âBeat ya to it! Shared on my social media and bought a book :)â

âI would love to hear what you think when you've read it,â Finicum wrote. âLets talk again.â

“They want something from me? They better take it from my cold dead hands.â

In the first pages of Finicumâs book, the cowboy warns that this fiction may one day come true. âIt is my belief that freedom will arise again in this land, but only after much blood and suffering,â he wrote. âThis is my witness and my warning.â Days later, having consumed the novel, Fry commented again: âJust finished your bookâŠMost Americans think they are going to hide in their bunkersâŠLittle do they know. You and I are on the same page though.â

âDavid, I am very glad that you enjoyed the book,â Finicum wrote back. âWe will rebuild this country once again and it will be done by good people who have foresight and determination.â

MacNab, the extremism expert, says Fry may have been drawn to Finicumâs warm personality. â[It is] empowering when you have someone that wants to hear what you have to say,â she says. And here was a man who commanded respect, who showed some semblance of control in the face of the adverse federal government, and who seemed to care about Fryâs ideas. âHe wasnât a loser kidâŠliving with his parents. He was important,â MacNab says. âAnd he was going to be a part of something bigger.â

A week later, Fry took his own virtual stand. In his first YouTube video, filmed with his cellphone, he stands in the gravel driveway of the familyâs home on a sunny afternoon, bugs chirping in the forest trees around him. Fry holds out a letter from a collection agencyâa notice of fines owed from the rafting incident. âThis is obviously tyranny. This is bullshit,â he says. âSo this is what I have to say: Iâm not going to pay these fines. I refuse to acknowledge this unjust law.â

He then sets the letter on the ground and holds a lighter to its edge, and then picks it up and fans the flame. âThis is how every American should treat these unjust laws.â

In the comments, someone cautioned that not paying would hardly make the fines disappear. Fry shot back, âIâm not gonna fork my money like a sissyâŠThey want something from me? They better take it from my cold dead hands.â

In the first week of January, 2016, the night before Bill and Sachiyo Fry were set to fly to Costa Rica on vacation, David arrived at the bottom of the stairs with a packed bag, his laptop, and a camera. He told his parents he was going to Oregon to be a part of the standoff there. His friend, LaVoy Finicum, was already there.

In the early hours of January 9, Fry posted to Facebook that he had arrived the previous night in eastern Oregon. The media there quickly noticed his presence. Fry didnât wear the costume of the typical Malheur Refuge occupier. He showed up with no weapons, no fatigues. His fellow occupiers raised an eyebrow. âI think heâs just gawking,â Jason Patrick, a protestor from Georgia, in late January. âHeâs not going to help us when the FBI rolls in.â But there among the crowds of prickly protestors was Fryâs internet pen pal, Finicum, who often stood next to Ammon Bundy at media microphones to lay out the occupantsâ demands.

Over the next 35 days, Fry uploaded 109 videos to his YouTube channelâheâs alone in most of them, but Finicum makes appearances in some. Most are strange, pointless moments from the occupations. On January 15, Fry showed himself eating a pork dinner. Four days later, he filmed a line of quails running across a snowy refuge lawn. On January 22, he made a four-minute video of himself walking through the dark to get a can of soda. Two days later, he filmed a ground squirrel. He calls to it, âHey! I see you! I see you, buddy!â

“This is gonna get real,â Finicum yelled. âYou want my blood on your hands?â

On January 26, on a curvy two-lane road north of Burns, the occupation came to a screeching halt. An FBI informant within the groupâs ranks tipped off police that a two-car convoy would travel that afternoon to John Day, Oregon, for a meeting with in another county who sympathized with the Patriots. When plainclothes officers in an unmarked vehicle pulled the cars over, Ammon Bundy and his bodyguard surrendered without incident. As Bundy was being cuffed, Finicumâs white Dodge pickup idled up the road. Finicum yelled out the driverâs side window that he would not surrender. He dared state police officers, pointing toward his forehead. âRight there. Put a bullet through it,â he screamed. âGo ahead, put the bullet through me!â

Finicum âBundyâs brother, Ryan, the Bundy familyâs 59-year-old personal secretary, Shawna Cox, and an 18-year-old gospel singer named Victoria Sharpâif they wanted to get out. None did.

âOK, boys? This is gonna get real,â Finicum yelled again out the window. âYou want my blood on your hands?â

âWe should have never stopped,â Ryan Bundy remarked as officers shouted for the occupants to come out.

âBetter understand how this thingâs gonna end,â Finicum told the officers. âIâm gonna be laying down here on the ground with my blood on the street, or Iâm gonna go see the sheriff.â

Finicum lowered his voice and called calmly over his shoulder. âIâm gonna go. You guys ready?â The people in the backseat crouched.

At that, Finicum stomped the accelerator and sped down the curved road. As he rounded a bend toward a police roadblock, Finicum jerked the steering wheel to the left, narrowly missing a law enforcement official, and crashed into a snowbank. Finicum jumped out, hands raised. Bullets shattered the windows of his truck, Sharp screaming as they hit.

âGo ahead and shoot me,â Finicum yelled at them. âYouâre gonna have to shoot me!â

In the interior left pocket of his denim coat was a nine-millimeter Ruger pistol with one bullet in the chamber.

Finicum reached for itâonce, twice, three times. Then officers reacted, firing three bullets in quick succession, splattering Finicumâs blood in the snow.

It was exactly the end heâd written in the final pages of his book.

Word of Finicumâs death sent the remaining occupiers into a panic. Some ran for their trucks and sped toward Nevada, Idaho, and Arizona. One man walked until he was picked up by police and arrested. On the night of January 26, Fry walked outside in the pitch black and filmed another video. âIt sounds like they arrested a couple of our guys and maybe shot one of them and killed them,â he whispered. âSo this is probably the last transmission youâll get from me.â

Fry called his parents to tell them what happened. âUp to that point, he wasnât scared at all,â Bill Fry says. Hearing of Finicumâs death terrified Fryâs parents. âI was worried about Davidâs life,â Sachiyo says. The Frys were gentle on the phone. They didnât want to have to fight him to come home. âThe last thing you want to do is have an argument with him and the FBI comes in and kills him that night.â For the next two weeks, the Frys talked to their son as often as they could. Fryâs videos took on a new tone. In them, he stationed his camera on top of his car, observing the Andersonsââpatrolling the refuge grounds with weapons. When Fry passes by the camera, heâs wrapped in a down comforter, a bandolier filled with ammunition around his waist.

On the night of , as the FBI surrounded Fry, Banta, and the Andersons in their tent, Bill Fry called his son one last time. Sachiyo leaned in to talk. They patched in Daniel. Bill is reluctant to share any details about the 20-minute phone conversation. âThatâs our family conversation we had.â

The next morning, David lay down on his sleeping bag with a gun to his head. He reiterated on the phone that he was willing to die for this cause. âThe tree of liberty must be watered with the blood of tyrants and patriots,â he said on the livestream.

, negotiators pleaded with Fry. The preacher asked him to pray. The livestreamers begged him to keep going and keep fighting. He yelled. He ranted about abortion and bombings in the Middle East, about Fukushima and police shootings and marijuana laws. He spat criticisms at everyone listening who wasnât present for not joining the movement when it mattered, for turning the other cheek at a government oppressing its people.

Just before noon, Fry issued one final demand: âIf everybody says âhallelujah,â Iâll come out. Will you? Will you do that?â Fry stuck a cigarette in his mouth, flicked the lighter one last time. âAlrighty then,â he said, drawing in a breath.

șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍű the tent, Fry heard voices: âHallelujah,â someone yelled. All around, men yelled, âHallelujah! Hallelujah!â Fry calmly emerged from the tent. âHallelujah, David! Keep walking, my friend! Hallelujah!â

Over the course of the next eight months, 11 of the 26 people arrested would plead guilty, and one would see the charges against him dropped the day before trial. The remaining 14 cases were split into two trials. Seven defendants will go to trial in February. Trial for the other sevenâthe Bundy brothers, Cox, Banta, Neil Wampler, Kenneth Medenbach, and David Fryâbegan on September 13.

That day, Fry was escorted into a federal courtroom in downtown Portland. For the first time in eight months, he wore clothes that werenât issued by the jail. He wore a baggy sweater, and his ponytail had grown halfway down his back. He sat silently, occasionally resting his head on the wooden table in front of him, as he had in pretrial hearings over the past few months. Around him, the other defendants argued with the judge. They pestered her for her oath of office and argued about why they should be allowed to wear cowboy boots and belt buckles in front of a jury.

Of the seven people on trial this fall and the 26 more named in a federal indictment, Fry was the only one kept behind bars with the Bundy brothers. The others were determined unlikely to flee and were released without bond. Neil Wampler, a man convicted of , was granted pretrial release. Kenneth Medenbach, who has been initiating skirmishes with government officials over land-use issues since the 1990s, is also out of jail. Same with Jeff Banta, one of the âfinal fourâ holdouts. The seven members of the occupation are all accused of conspiring to impede federal officersârefuge employeesâfrom performing their official duties. If convicted, each of the accused could go to federal prison for . Five of them, including Fry, were also accused of carrying firearms in a federal facility, which would add to any imposed sentence.

After Fryâs arrest, authorities found a trove of guns in his car.

In the eight months heâs spent in jail, Fry has been placed in solitary confinement twice, according to his father. At those times, he gets just 15 minutes out of his cellâjust enough time to shower. When heâs in the general population, though, Bill and Sachiyo call him every day. They say he misses the food at home. He asks about his rabbits and the family dogs. In jail, heâs turned to a vegan dietâhe doesnât want to gain weight.

On September 13, as the trial began in front of an all-white, mostly female jury, Fryâs attorney, Per C. Olson, painted a portrait of a man apart from the Patriots. Before January 26, the day Finicum was shot and killed, Fry, whom Olson called âa little bit of an oddball,â was barely noticed at the refuge. Afterward, Olson said, Fry unraveled. âMr. Fry is and was a young man who is troubled by a lot of things in the world,â Olson said. âItâs difficult for him to turn that offâŠThe corruption of the world and horrors of the worldâhe canât turn that off.â

Olson, who declined șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍűâs repeated requests for interviews, told the jury that Fry was diagnosed with a condition called schizotypal personality disorder while in jail. It âseriously affects how he perceives the world and the actions of others,â says Olson, and âresults in very unusual thinking patterns.â Fry was simply caught up in the middle of chaos, Olson said, and thought his livestreaming could prevent another Ruby Ridge or Waco. âHe believed he had this role to protect them.â

Two weeks later, on September 27, attorneys for the government argued that Fry wasnât simply an innocent documentarian. After Fryâs arrest, authorities found a trove of guns in his car: an SKS-style 7.62mm rifle, a Steyr PW Arms 7.62x54R caliber rifle, a New England Firearms 12-gauge shotgun, and a Winchester model 94A .30-caliber rifle. Two were loaded. None were registered to him. (Bill Fry says his son gathered up all the guns at the refuge so they were safe.)

Online, Fryâs YouTube channel, called âDefend Your Base,â continues to be updatedâthough Bill Fry isnât sure whoâs posting. Several recent posts include recorded phone calls from Fry in jail. âThanks for the letters, everybody,â he says in one. âHallelujah. Iâll talk to you later.â

A few days into the trial, Ammon Bundy appeared in blue jail scrubs to look the part of a political prisoner. Audience members in the gallery mimicked him in a show of support. On another day, a woman entered the courtroom in a T-shirt stenciled with a cowboy silhouette and the words âFree Ryan Bundy.â Every day, there is someone with a pin or a shirt bearing Finicumâs face. A man in front of the courthouse passed out pocket Constitutions, fliers about Finicum and the Bundys, and granola bars. They waved American flags. Few mentioned David Fry. The movement Fry was so eager to join, so loyal to until the very end, appears to have forgotten him.

In a packed federal courthouse in downtown Portland on Tuesday, October 4, Bill Fry took the witness stand, seated 15 feet from his son. It was the closest heâd been to David in months. Sachiyo looked on from the gallery. Four floors above, another courtroom was at capacity, filled with people watching a livestream of the trial.

Wearing a suit and an American flag necktie, his gray hair brushed back, Bill Fry told the court his sonâs story from the beginning: the familyâs deep military history, the racism his boys encountered at school, Davidâs passionate beliefs about abortion and Fukushima. He said his son has never touched two of the guns heâd been given as gifts. He recalled the night before he and Sachiyo left on vacation and the moment David arrived at the bottom of the stairs with his bags and announced he was going to Oregon.

In trying to account for why his son decided to devote himself to a Patriot protest at a wildlife refuge in Oregon seemingly out of the blue, Bill told the court that the situation offered David the opportunity heâd been seeking for years: âHe wanted to go somewhere where the world was listening.â