2,000 Sacred Bones Went Missing 21 Years Ago

In the 1990s, thousands of bones and bone fragments mysteriously went missing from Effigy Mounds National Monument in Iowa, the continental epicenter of Native American burial remains. In December 2015, a detective with the National Park Service tracked down the artifacts—and the man who stole them.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

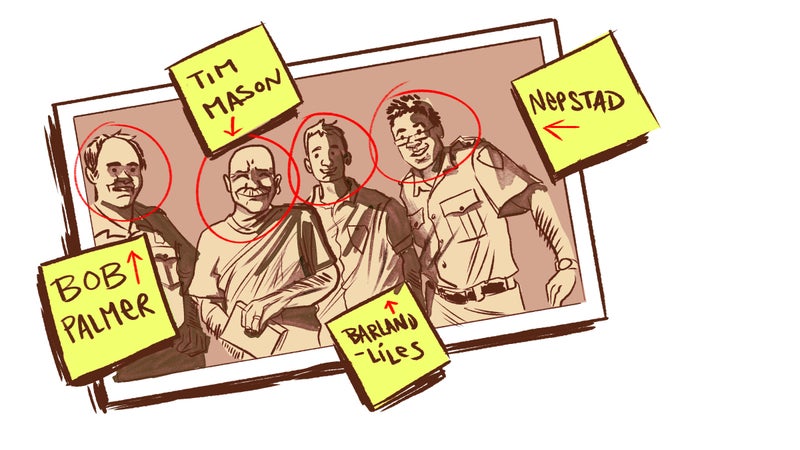

Jim Nepstad was nervous about meeting with the tribes. It was June 2011, just six months after he’d transferred to , in northeast Iowa, a park created to preserve centuries-old burial mounds that held the remains of hundreds of Native Americans who once inhabited the upper Midwest. The stakes were high: This was Nepstad’s first superintendent posting after 27 years in the National Park Service, most recently as chief of planning and resources at , in Wisconsin, and he arrived with a mandate to clean up a scandal involving a pattern among park staffers of desecrating Native American grave sites.

Media coverage of the issue was turning the 2,256-acre park into a major source of embarrassment for the Park Service, and representatives of the 20-some-odd American Indian tribes that claim a cultural or genetic link to the park were seething. Most felt the Park Service had ignored the sullying of sacred sites. Nepstad’s job was to assess the physical damage, repair relations with the tribes, and bring competency back to the little park. Instead, he was about to reveal another, even more disturbing problem: Almost all the ancient human remains under the park’s care were inexplicably missing, and no one had a clue where they were.

The park was already an epicenter of controversy. Between 1999 and 2010, under superintendent Phyllis Ewing, Effigy Mounds essentially went rogue. According to a Park Service investigation report published in 2015, Ewing and her staff either skimped on or ignored reviews, which require any federal building project to be vetted for archaeological impact. Ewing and her team . They developed once-sleepy hiking trails into ATV maintenance roads and installed a five-ton steel bridge over a creek without conducting a proper impact report. They built three elevated boardwalks, one of which punched hundreds of postholes into an archaeologically sensitive area home to the remnants of 60 mounds. They built a maintenance shed over part of a hidden burial mound. All of this happened under the noses of their superiors at Park Service headquarters, who didn’t catch on until a former employee turned whistle-blower brought the projects to their attention in 2010.

In early 2011, after a representative of one of the tribes affiliated with the park requested an inventory of the park’s remains, an administrative assistant named Sharon Greener placed an orange binder on Nepstad’s desk and told him, “You should probably read this.” As he paged through the report, compiled in 1998, he noticed a disturbing pattern: Skull fragments, tibia, vertebrae, and other human remains that were once housed in the park’s small museum were listed as missing. In all, more than 2,000 bones and fragments belonging to at least 41 people, including newborns, children, and their families, were unaccounted for. Even worse, they had been missing for well over two decades, and no one, it seemed, had made a serious effort to find out what happened to them.

Almost all the ancient human remains in the park’s care were inexplicably missing, and no one had a clue where they were.

“Here, I had come into this park having made public statements that we were going to get this stuff straightened up and get this park flying right,” Nepstad says. “Then, within less than four months of arriving, I’m confronted with this situation.”

Going into the meeting with Nepstad, the tribal representatives didn’t know to what extent the park had mishandled the bones. As Nepstad explained the situation, the mood around the conference table darkened. Human remains did not simply disappear from a museum collection. There should have been a very strict chain of custody, and even improperly handling them is a federal crime. Any movement of remains out of the collection had to be officially documented, or “deaccessioned.” But Nepstad hadn’t found any paperwork on them, raising the possibility of foul play. Had someone stolen the bones, he wondered?

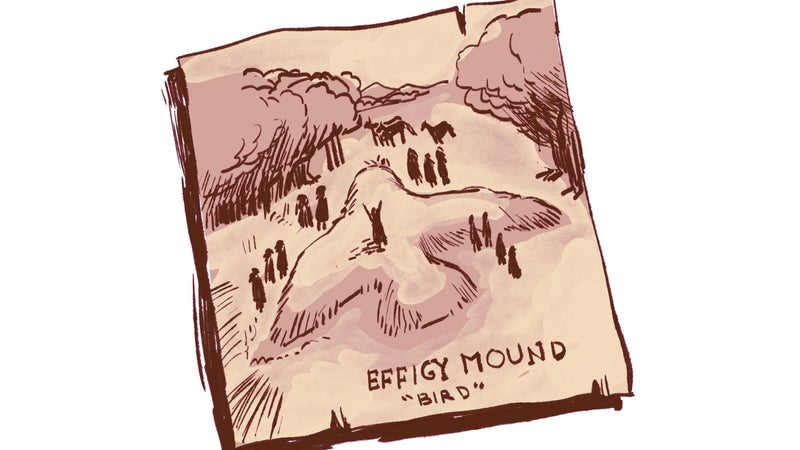

There are tens of thousands of burial mounds in the United States, most of which are east of the Mississippi and were built by Native Americans over millennia, from about 3,500 B.C. until the 1600s. Most mounds are simple conical or linear rod-shaped structures made by piling dirt into earthworks. But between 700 and 1,100 A.D. in the upper Midwest, a confederacy of culturally similar communities known as the Effigy Moundbuilders transformed mound building into an art form. They designed elaborate effigies in the shapes of animals—geese, bears, wolves, hawks, and even more fanciful creatures like water spirits. In some areas, dozens of cones and effigies literally fill the landscape. Like , they are most impressive when viewed from the air.

The majority of these mounds, several thousand of them, are found in southern Wisconsin. But some, like the 206 burials at Effigy Mounds, emerged along the banks of the Mississippi River in Iowa, as well as parts of northern Illinois and southeastern Minnesota.

Beyond serving as burial sites, the significance of the mounds is unclear. Some archaeologists believe the small communities of Woodland Indians would meet once a year to feast, celebrate, and communally bury the remains of relatives by building a new mound. The communities eventually disappeared, but succeeding native groups, some of which were pushed into the upper Midwest, many of which were pushed westward by European settlers, adopted the mysterious mounds as their own.

White settlers who moved into the area in the mid-1800s, however, treated the mounds with the level of care you might expect: Up to 80 percent of the mounds were simply plowed over, and any remains inside were ground into the dirt. All of them might have been lost if not for the curiosity of academics and amateur archaeologists who began examining the phenomenon and recording the locations and shapes of the mounds.

Some of the most impressive mounds along the Mississippi were secured when, in 1949, President Truman established the 1,000-acre Effigy Mounds National Monument. (The park was later expanded twice.) Despite gaining federal protection, however, archaeologists were still allowed to excavate the park’s burial mounds and remove remains throughout the 1950s and into the 1970s. Some of the bones and artifacts buried with the dead were collected and put on display for a time in the Effigy Mounds visitor center, but most ended up in a small collection space in the basement.

By the 1970s, Indian civil rights groups who believed that unearthing, examining, and in some cases publicly displaying their ancestors’ remains constituted a cardinal sin, were raising their collective voice. “I can remember vividly an elder statesperson from a tribe telling us it was possible we could be visited by [the American Indian Movement], and that things could turn hostile,” says John Doershuk, Iowa’s state archaeologist. In 1976, under pressure from the tribes, , effectively halting archaeological work at Effigy Mounds.

A milestone in the national fight to respect and repatriate Indian remains came in 1990, when , requiring any agency or institution receiving federal funds to catalog all the remains in their possession within five years and begin returning them to tribes. “NAGPRA is one of the most critical pieces of Native American human rights legislation ever passed by Congress,” retired Republican Colorado senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell said in a 2015 press release. “It protects that which is most sacred to all of humanity; the right to be buried in accordance with our own religion and under the same soil as your relatives.”

In April 2011, on the day Nepstad learned about the missing remains, he approached the park’s sole law enforcement officer, Bob Palmer, who worked seasonally at the park for more than 20 years. Had Palmer heard about any bones disappearing?

Palmer hadn’t, but he did remember a conversation he had the previous summer with Thomas Munson, superintendent at Effigy Mounds from 1971 to 1994. Munson had told Palmer that a box of animal bones had gotten mixed up with his belongings when he moved from park housing in 1990 to his home in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, just across the river. It seemed strange to Palmer that Munson would have found an errant packing box 21 years after moving, but he told Munson to keep the box until a new superintendent arrived. But now, listening to Nepstad, Palmer wondered if there could have been a horrible mistake. “I put two and two together, and I told Jim [Nepstad] I may know where this stuff is,” Palmer says.

What kind of person would steal human bones from a national park?

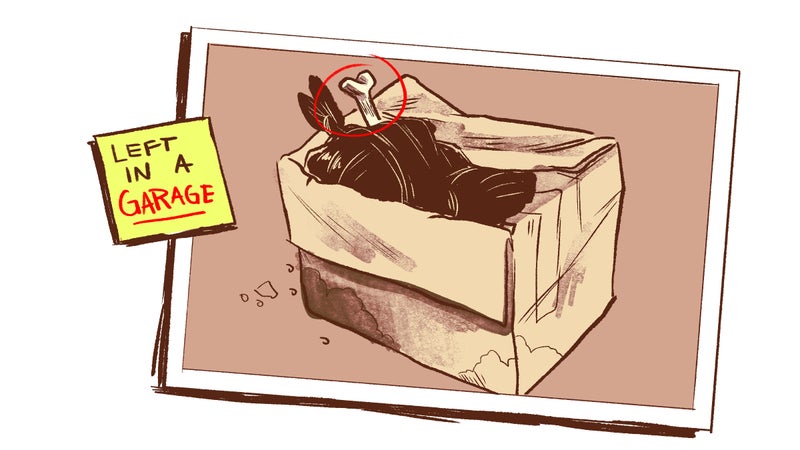

The same day, Palmer drove across the river to Munson’s home to ask him about the box. The former park chief, then in his 70s, rummaged around in his garage for a bit but said he couldn’t find it. A day later, Palmer got a call from Munson: He’d found the unmarked moving box, and could Palmer please pick it up? When Palmer got the box back to his office, he folded back a black trash bag inside. “I opened it up, and that’s what it was—human remains with the museum numbers on them.”

With the remains at hand, Nepstad and Palmer thought the whole affair was behind them. But a few weeks later, an archaeologist’s inventory revealed that the box held only about one-third of the 2,000 missing bones and fragments. During a follow-up phone call, the former superintendent suggested they check the attics and crawl spaces in park buildings. The state archaeologist’s office confirmed that the box contained only about one-third of the missing remains. The rest were still missing.

As Nepstad and his rangers continued looking for clues on park property, they finally came across the deaccession report, deep in the park’s files, detailing the missing bones. But it was strange: The human remains hadn’t been sent to another museum or borrowed by a university. Instead, in July 1990, the missing human remains had been marked as “abandoned,” a term reserved for objects determined not to be archaeologically significant, like clods of dirt. There was no way anyone could mistake the museum’s bones for trash. More perplexing was the signature on the report:

Special Agent David Barland-Liles investigates museum thefts and other crimes for the , and he was familiar with the issues at Effigy Mounds. He’d probed the park’s construction violations and produced a blistering report about the incidents, concluding that former superintendent Phyllis Ewing showed “willful blindness” to the law with regard to building projects in the park during her tenure. (The U.S. Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute Ewing or her staffers. Ewing, who declined to comment for this story, filed a lawsuit against the Park Service in 2015, claiming she was a scapegoat for larger Park Service failures and had not been properly trained. The suit was eventually dismissed.) When Nepstad called him in late 2011, Barland-Liles was glad to help.

Learning about the missing remains, though, was upsetting: What kind of person would steal human bones from a national park, Barland-Liles wondered? And what would their motive be? “The hair stood up on my arms when I realized what I was up against,” he says. This wasn’t just some honest mistake or bureaucratic snafu. Someone, or a group of people, committed a crime and attempted to cover the trail. “There was no doubt,” Barland-Liles says. “I started going down the road to find the truth. I had two goals: Let’s find the rest of these people, and let’s find justice.”

Barland-Liles began systematically reviewing everyone who worked at Effigy Mounds between the 1980s and late 2000s, and a timeline began to emerge. He found that several staffers had noticed the missing remains and tried to investigate, but anyone who attempted to dig deeper had been told by Thomas Munson that it wasn’t worth pursuing.

Roughly a year after Munson’s retirement in 1994, new superintendent Karen Gustin wrote a memo stating that the remains were gone. When she talked to Munson about them, he said the bones were probably sent off to the state archaeologist or the Park Service’s , and never returned. Katherine Miller, who took over as superintendent in 1997, also called Munson when she learned the bones were missing. He told her a different story—that he remembered storing the bones in a metal locker in a park maintenance shed. Munson speculated that the remains were probably forgotten there and thrown out with the locker.

Miller, however, did not let the issue rest. She reached out to Dale Henning, an archaeology professor at nearby Luther College, to track down the remains. Though he wasn’t able to locate them, Henning produced . (It was Henning’s report that eventually landed on Nepstad’s desk in 2011.) There’s no evidence that anyone at the park continued the investigation after Ewing took over in 1999 until Nepstad reopened the case 12 years later.

On January 18, 2012, Barland-Liles met Munson at his house while Munson’s wife, Linda, was away. The superintendent, then in his early 70s, was cooperative, but he refused to allow their conversation to be recorded. He told the investigator yet another story, claiming he received a call from an unidentified source at the Park Service asking him to send the remains to the Midwest Archeological Center, and that he personally drove a box of remains to Lincoln, Nebraska, where Park Service staffers removed it from his car. The other box had been accidentally put in his garage during the move from park housing.

“The truth was becoming more and more scary and dark. It was making the Park Service a little nervous. But since, as an investigator, I had a different chain of command and a singular mission, I got to ignore that and march forward.”

But Barland-Liles had done his homework. Park documents showed Munson completed his move to Prairie du Chien at least three days before he signed the deaccession paperwork, meaning the remains were still at the Effigy Mounds visitor center after the move and could not have been accidentally mixed in with his possessions as he’d claimed. The Midwest Archeological Center had no records of receiving the remains from the park. “Dates on the forms don’t mean anything,” Munson told Barland-Liles, according to the investigator’s notes. “I can’t explain all those discrepancies.”

Barland-Liles left Munson’s home thinking the former superintendent was either hiding something or was perhaps deeply confused. That same day, he interviewed Sharon Greener, who was still an administrative assistant at Effigy Mounds. She said that in 1990, Munson, superintendent at the time, instructed her to find all the remains in the park’s collection and bring them to his office. Munson instructed Greener to type up the deaccession report and mark the bones as abandoned, though as a new seasonal employee, it’s unlikely she knew she was doing anything illegal. The task made her uncomfortable, Greener told the investigator, and she didn’t believe the remains were getting the respect they deserved by being placed in cardboard boxes. But she wasn’t in a position to object. “I blindly listened to Tom [Munson] tell me to do it,” said Greener.

All the clues pointed toward Munson, but Barland-Liles needed to figure out how they had disappeared. “The noose was tightening, and the ability of people to make up stories was ending,” he says. “The truth was becoming more and more scary and dark. It was making the Park Service a little nervous. But since, as an investigator, I had a different chain of command and a singular mission, I got to ignore that and march forward.”

Understanding a perpetrator’s motives can bring order to the facts of a case, but Barland-Liles was at a loss: Why would someone in Munson’s position steal bone fragments under his care and hide them away for 21 years?

In an interview with Barland-Liles, a former chief of maintenance under Munson named Tom Sinclair shed some light on the superintendent’s possible reasoning. According to his account, as Congress prepared to pass NAGPRA in 1990, Munson became paranoid that tribes would use the new law to assume control of Effigy Mounds National Monument, including the artifacts and remains within it. Such interference would erase the historical record pieced together over decades by dedicated archaeologists. Munson tied up the park’s single phone line discussing his theories with a fellow superintendent at Pipestone National Monument, another archaeologically significant park, in southwest Minnesota, Sinclair told the investigator.

Munson wasn’t alone in his fears about the new law. Others in the archaeological and research communities anticipated that NAGPRA would deal a blow to the bedrock of North American history. “They were concerned about returning skeletal remains and artifacts because, at the time, they viewed these as purely scientific objects,” says Robert Birmingham, former state archaeologist of Wisconsin and a leading expert on effigy mounds. “There was a sense that they were taking away objects of study that would inform us about ancient societies in the Americas.”

There had been other obstructions of NAGPRA. In 1998, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln confirmed that in the 1960s, the anthropology department burned American Indian remains found in archaeological digs in the veterinary school incinerator because they felt the remains had no scientific value.

The problems have continued. In 2013, Patrick Williams, who worked as a museum specialist at the , the agency that constructs dams and waterways in western states, claimed the agency had been ignoring NAGPRA for decades. According to a 2014 whistle-blower complaint facilitated by , a government watchdog group that monitors problems in the Park Service and other agencies, the office stored 164,000 uncataloged artifacts and remains collected during construction projects in cardboard boxes in their Sacramento headquarters and allegedly altered databases to erase the records of some remains.

“We hear things all the time,” says Jeff Ruch, PEER’s executive director, who was instrumental in publicizing the Effigy Mounds Section 106 violations. “But we can’t act on NAGPRA violations unless someone comes forward to make it public.”

On May 16, 2012, after six months of investigation, Barland-Liles was sitting in the basement of the Effigy Mounds visitor center, where the missing bones were once stored, when Sharon Greener reiterated her story—but with a new detail: In 1990, she had helped Munson carry two cardboard boxes full of bones from the visitor center basement to the trunk of Munson’s Ford Taurus. Greener said she believed at the time that Munson was either going to bury or dispose of them somehow, and she didn’t push for answers.

It was the last time anyone saw the missing remains—the final clue Barland-Liles had been searching for. It confirmed that there were two boxes, not just one, and that both were at one point in Munson’s possession. “The clouds lifted,” Barland-Liles says. “It was one of the most important days of my career.”

The next day, Barland-Liles parked his SUV in front of Munson’s two-story brick home a few blocks from the Mississippi River. It was, and remains, the nicest house on the street, with mature trees, a fenced-in backyard, and a white clapboard two-car garage hidden at the rear of the house.

Munson’s wife, Linda, invited Barland-Liles inside. She was spry and energetic and wore white tennis shoes. Her husband was stooped and frail-looking, with a wry expression on his face. The investigator asked Linda to stick around. He explained that her husband was involved in a Park Service investigation, and that there were inconsistencies in his stories. The three sat in the living room, the couple across the coffee table from the investigator.

Barland-Liles presented his findings: documents showing that the Munsons had moved before the remains disappeared; a statement from Karen Miller that Munson had told her the remains were in a storage locker at the park, which was at odds with his story about driving the bones to Nebraska. He told Munson that the Midwest Archeological Center had no record of him delivering a box of bones. There was no evidence that any shadowy Park Service official ever instructed superintendents to dispose of Native American remains. In fact, memos showed that just the opposite—superintendents were instructed to fully comply with NAGPRA.

Barland-Liles paused and looked at the couple. Munson was stoic, but Linda’s expression had turned grim. “I’m guessing no one told you to do this,” Barland-Liles said to Munson. The former park chief just shrugged his shoulders. After a moment, Munson spoke, admitting that he’d made up the story about driving the bones to Nebraska. Then he got quiet, as if he didn’t have anything more to say. Linda broke the silence.

“What do you believe happened?” she asked Barland-Liles. He leaned forward in his chair and looked at her. He said he didn’t believe the boxes were accidentally moved or shipped out of state or mislabeled. He believed that for 22 years, through 100-degree summers and freezing winter nights, the remains of 41 people had sat in her unheated garage, slowly crumbling to dust. Linda went quiet, absorbing the information. “In the end, it came down to his wife accepting that I was telling the truth and her husband wasn’t,” says Barland-Liles.

On top [of the bag] was the rounded stump of a femur marked with a spot of whiteout with catalog number on it. “I think this is what you’re looking for,” she said.

The investigator reached into his briefcase and produced a “consent to search” form. Linda promptly signed it, then slid it in front of her husband. Munson hesitated. Linda patted the paper. He lifted the pen slowly and signed his name.

The three of them walked out the back door into the bright May evening. Munson stopped at the edge of the lawn while Linda led Barland-Liles through the side door of the garage. It was orderly and clean—not the type of place where boxes go missing. The pair homed in on a medium-size moving box, slightly collapsed at the top, printed with the words “C-A-T Moving” and a cartoon of a jaunty feline in overalls. The box was just a couple feet in front of the Munson’s white SUV, between a black metal Jerry can and a handmade board for the card game One-Eyed Jack. Just a few weeks before, the Munsons had moved a porch swing covering the box into their yard. Linda bent over and lifted open a flap revealing a black plastic bag. On top was the rounded stump of a femur marked with a spot of whiteout with catalog number on it. “I think this is what you’re looking for,” she said.

“I was shocked. I never thought I’d find them,” Barland-Liles says now. “Munson had 21 years to get rid of them. The trash man shows up every week. The Mississippi River is right there. I’m not sure I will ever understand.”

After photographing the scene, Barland-Liles took the box and placed it on the passenger seat of his SUV, then locked the doors and walked back to the house to have a final word with the Munsons. “They began to realize they were in trouble, or Tom was, which was a surprise to them,” Barland-Liles says. “They asked me if they needed a lawyer. I said, ‘You might.’”

Munson did need a lawyer. The U.S. Attorney’s Office . He reached a plea deal in which he copped to one count of “embezzling government property, human remains.” In July 2016, four years after confessing to Barland-Liles, Munson was sentenced in a court in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He received ten consecutive weekends in prison, one year of home confinement, 100 hours of community service, and a $3,000 fine, and he was ordered to pay $108,905 in restitution—the estimated cost of analyzing and cataloging the remains he stole.

The tribes were disappointed. They wanted Munson to go to trial for his crimes. But the U.S. Attorney’s Office explained that criminal charges may have extended the length of the process, which, due to Munson’s age (he was then 76) and poor health, presented the possibility that he may never see justice.

More aggravating to some was Munson’s apology. During his sentencing statement, he claimed his theft “wasn’t intentional.” His lawyer tried to excuse his client, explaining that Munson suffered from congestive heart failure and cognitive difficulties. Munson also sent a written apology to the Park Service and the affiliated tribes and produced a video apology (in which he read his written apology on camera), which was never made public. Patt Murphy, a NAGPRA representative with the , wasn’t satisfied. “The only thing he wrote in that apology was his signature,” Murphy says. “It was condescending, and he didn’t admit to anything.”

Sharon Greener was not charged with a crime, but the Park Service fired her for initially withholding the information about Munson removing the boxes from the park. Greener, for her part, claimed she was being used as a scapegoat, when in fact she was whistle-blower. She argued that seven times between 1990 and 2012, she either told superiors about the missing bones or gave them the 1998 inventory report, hoping to trigger an investigation. In 2014, the Park Service settled with Greener, agreeing to pay her two years of back pay, lawyer’s fees, and an undisclosed one-time sum for “compensatory damages.”

Jim Nepstad is trying to move the park forward after the scandal. Effigy Mounds is bringing on a new staff of archaeological and cultural resources professionals, including a former tribal historic preservation officer for the . “I will spend the rest of my time here in a rebuilding process, until we can demonstrate consistently to the tribes that this type of thing will never happen again,” Nepstad says.

Thomas Munson’s motivations may never be fully understood. “Munson was from an era that saw science as the ultimate end of knowledge,” says Bob Palmer, a former chief ranger at Effigy Mounds. “Think of people born in the ’30s and ’40s, who saw the development of atomic energy and the massive advancement of science. I would suspect Tom Munson’s perspective on Effigy Mounds was that the archaeology and science were more important than anything else—more important than respecting native cultures.”

“The only thing he wrote in that apology was his signature. It was condescending, and he didn’t admit to anything.”

Patt Murphy believes that Munson simply committed a racist and bigoted act—part of a long continuum of actions by the government and individuals against native peoples. “He thought those funerary objects were more important than people,” Murphy says. “His attitude was that we are animals. He kept our bones in his garage and told people they were from animals.”

David Barland-Liles says he has not heard of a similar crime taking place in another national park, but that it could have. “If it happened here, I have reason to believe it happened somewhere else,” he says. “The agency has to grow and recognize that it’s set up in a weird way that gives superintendents little oversight, and that allows people to do something like this right under our nose.”

There is no ceremony for reburial, at least not among the tribes associated with Effigy Mounds. They believe that once a body reaches its final resting place, it’s meant to stay there. So, next spring, when the ground thaws, a small group of tribal representatives and park employees will gather to reinter the bone fragments, likely at a secret spot on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi. The bones will return to the earth near some of the mounds where their kin remain, undisturbed for centuries. The elders may bless the ground or leave some tobacco before covering the brittle bits of cranium and vertebrae with earth, before the location is recorded with a GPS and they are left to rest without a monument or marker.

Until then, the bones of 41-some-odd people will sit in a box sealed with evidence tape in the secured basement of the Effigy Mounds visitor center, which they’ve called home for the past four years. Even the superintendent doesn’t have access; only the park’s archaeologist has a key to the room. It’s climate controlled, but otherwise not much different from the garage where they rested for decades. But at least now they are treated with respect. For now, everyone knows where they are.