After

damaged the New Jersey coast in

1985, the (FEMA) asked the state’s

to estimate the coastal effects of the storm.

The state agency wasn’t sure, because they didn’t have an accurate baseline. “I

mean, they had some Polaroid pictures, and that was it,” says coastal researcher . “They had no data, no surveys, no map, no

�ԴdzٳԲ�.”

Farrell put together a proposal to start surveying the

coast, got the go ahead, and founded the

at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey in 1986.

He has conducted coastal surveys every spring and fall since. By late October, he was nearing the end of the 2012 fall monitoring. “But Sandy hit,” he

says. “Now we’re going back and seeing how much dune and beach are missing,

because somebody’s gotta come up with a number for how many cubic yards of

sand we’re going to need to fix things.”

Every morning since the hurricane struck, Farrell has driven

and walked the coast to survey . That includes weekends. So far, he’s

captured Atlantic, Cape May, and Ocean counties. His groundwork will be

combined with aerial surveys and computer models that offer a fuller sense of

the damage, but even right now the effects of the storm are clear. “It’s the

worst event in my career, which goes back to the 1960s,” he says.

We called up Farrell this past Friday afternoon, after he

returned from surveying damage in the borough of Avalon, to find out more.

Do you have any idea what percentage of coastline has been damaged or eroded?

Well, it’s all still there. It’s just been rearranged. The sand hasn’t gone

anywhere. It’s just not where we want it. A lot of it, in some places, was

washed inland on to the barrier islands, and that’s going to be tough to get

back, because it’s in among the houses and bushes and trees and everything.

They’re moving it off the streets and the roads and putting it back on the beach,

but that’s not going to put it all back by a long shot. Some of it is offshore

and is forming into bars that will eventually move back onto the shoreline.

They always do. That’s not going to fix the dunes. The dunes take decades to

build naturally. So we—that’s a collective we—are going to have to bring in

sand from somewhere and rebuild a dune system.

How does a rebuilt dune system compare to a natural dune system as a buffer to storms?

They’re both basically piles of sand. Most of them were manmade anyway.

The natural dune process has not been … if you go to Island Beach State park,

those are natural dunes. The only difference is that the plant root system is

all through the dune so they are kind of wired together better than a manmade

dune.

How has you work

evolved over the years?

We work closely with the in Tom’s River. As a result

of the work we do with them, the effect has been to work with the federal

government for beach nourishment projects. In 1994 the state passed what they

called the .

In the last decade or so they’ve funded $25 million a year for coastal

projects. They use it as leverage to acquire federal coastal projects through

the Army Corps of Engineers. And the Army Corps of Engineers will undertake a

project for shore protection—it’s what they call them; they’re not called beach

nourishment, they’re called shore protection projects—if the benefits of doing

it outweigh the costs by 1.25. So if you divide the benefits by the cost, and

the resulting fraction is 1.25 or greater, they’ll agree to do it. The benefits

are essentially damage reduction. So they have done a fairly good degree of

projects. Between the state and the feds, 55 percent of New Jersey’s 97 miles

of shoreline had a beach project since 1986. All of this was primarily driven

by the fact that New Jersey is the only state that has a stable funding law

providing $25 million annually.

So the reason for 55

percent of the state’s 97 miles to get this protection is because of the

development? By nourishing, or protecting, the beaches you're limiting the cost

of damages. Is that the way to look at it?

That’s the way it’s looked at. They take each and every

segment of the New Jersey coast—by the Army Corps of Engineers—in terms of

historical storm damage, development, cost, and potential for future storm

damage and they come up with a design for a project. Then it’s up to the state

and the locals to partner with the feds to pay the other 35 percent and acquire

the rights to the shoreline for the real estate issues.

Now, one of the reasons it was never done for some regions

is because the individual property owners own to the high tide line. Getting

all of them on the same train looked to be like herding cats. You couldn’t do

it, and the Army Corps was not about to do the project without easements. So

that’s why they piecemealed projects in places like Long Beach Island. The

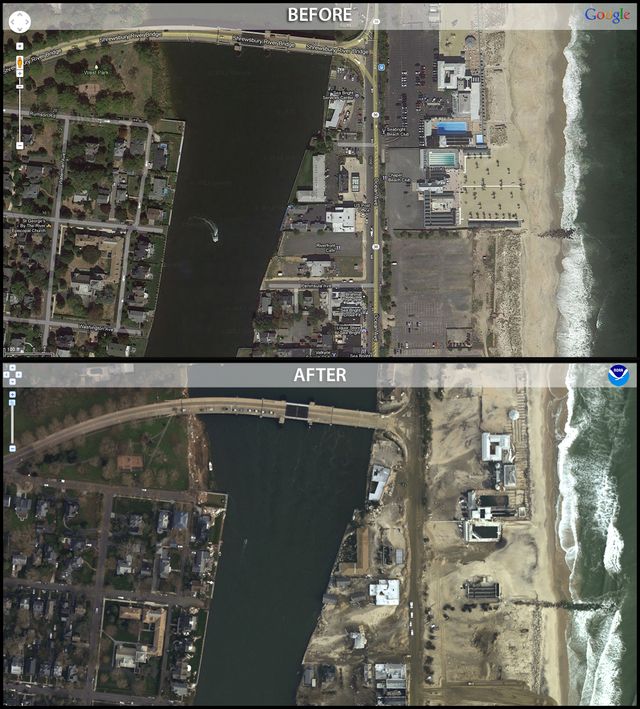

areas that were done did not suffer wave damage.

Can you describe the

economics of nourishing or protecting

these beaches? How much does it cost to do that every year?

Take, for example, . The whole island, 18 miles of it, received a $79 million Corps

estimate. They did about five miles of it. They did Brant Beach, Surf City, and Harvey

Cedars. Not counting the money they spent sieving the sand in Surf

City, they spent about $20 million, so that’s about $4 million a mile. Since

there was no damage to the homes, they probably did a pretty good job.

A lot of pictures in

the media are showing damaged home or flooded areas.

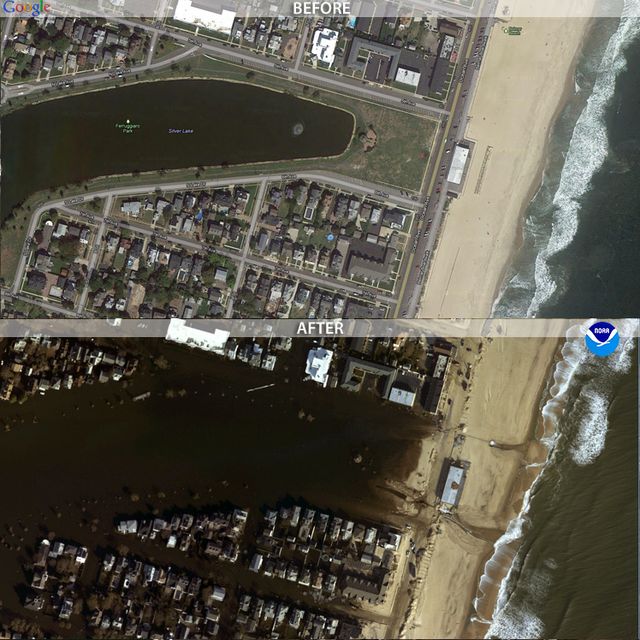

Well, there’s a big difference. Flooded areas don’t count.

That’s going to happen no matter what happens with beach projects.

What caused sand erosion

to be the worst situation on the coastline since you started working in the

'60s?

Well, north of the eye—that would be Long Beach Island,

Ocean County, Northern Ocean County, and Monmouth County, New York, of course,

Long Island—was more intense. It was less intense south of the eye, in Atlantic

County, Cape May County. So the intensity factor was more: higher storm surge,

bigger waves, more of them.

Can you describe the

storm surge and the power at the some of those beaches?

The buoys offshore said 25 feet. Now, they’re smaller by the

time they get to shore, but the storm surge was in excess of 12 feet. Some places

in the New York area were 14 feet. The previous record was 10’6”. Once they broke they were probably

about six feet high. They came rolling up and they did not treat the buildings

well. The buildings got one every 10 seconds. So for six hours you’ve got a

wave hitting a house every 10 seconds, leaving not much left of the house. The houses built on pilings generally did much better. There are a

lot of them these days. The houses built on a foundation, or piers, or

footings? Destroyed or seriously damaged. So how the house was built has a lot

to do with it. Now, those are going to be replaced, and I’m sure they’ll all

be on pilings.

Everything around the buildings, of course, has been wiped

away. You need an extension ladder to get to the front door now. So they’re

not terribly useful, but they’re still there.

What do you think the

major lessons have been from Sandy?

I have no idea. Some people are going to throw in the towel. Some of them are

going to build tougher and stronger. And some of them are just going to try to

replace what they have. I think that the state is going to have a few more

regulations: on how high the decks are above sea level, where the house can be

placed relative to the shoreline, and these beach nourishment projects may get

extended statewide, regardless of the property ownership. They could decide to

take the beachfront lot and say, “It's public now, sorry.” I haven’t heard anything about that, and it’s definitely

going to be a volatile issue if it is brought up. It’s property rights versus

public access, and it’s been going on for decades.

Do you think all of

this beach nourishment is a good idea?

Well, where it was not done you had virtually total destruction. Where it was

done the physical action from the wave damage was far, far less. I mean,

Atlantic City survived. No damage to the boardwalk on the oceanfront. They

squeeked by, but they still survived. The dune was just high enough. Avalon,

Stone Harbor, no damage. Strathmere, no damage. Cape May City, no damage. Harvey

Cedars, no damage. Holgate, . So there you go.

Is there another

option? Some people are calling for a reassessment of how much building is done

on the coast, near the coast, considering the amount of damage.

Well, that’s been suggested by many people. The biggest proponent of that was a professor down at Duke, . He has since retired, but is still

around. He was a big proponent of 'Get out of the barrier islands.' Ain’t

happening.

Why do you think that

won’t happen?

It’s where the money is. People like the beach, and property

ownership at the beach is not going to be made illegal. So managing it,

regulating it, is something that gets more stringent after Sandy. But I do not

see any way—I mean … look, New Jersey earns $36 billion a year off of it. So the sales tax is pretty

impressive. The jobs. There are 400,000 jobs related to the coast. Fifty million

people live within an hour of it, and it’s still there. You can go swimming anywhere

in New Jersey if you choose to, no problem. The water’s still wet, still salty,

still there. It was a beautiful day at the beach today—just a little chilly to

be strutting around in your bikini. But definitely still a gorgeous day at the

beach, and everything that’s broken can be fixed.

And how long do you

think it’s going to take to fix things based on what you’ve seen?

Two, three years. I mean, you got a quarter of the houses in Mantoloking

destroyed. They’re all 3,000- to 4,000-square-foot homes. Some of them are 100

years old. So there’s going to be some time. There’s just not enough tradesmen

around to build them all. You’re going to see the egregious evidence go away in

six months—the debris, the sand in the street, the other stuff—but the damaged

homes are going to take a while to fix. There are only so many guys that can

fix them. I mean, they’re going to be coming from the Midwest. The pick-up

trucks are going to be everywhere.

Things weren’t normal after the 1962 Northeast storm until

1968, and by then they were beginning to forget about it. Properties changed

hands. Right now, you could probably pick up an oceanfront property for maybe a

million two. Maybe less, I don’t know. I haven’t seen any sales figures, but that’s

what happened last time. You could buy an oceanfront lot for $5,000 in 1962 in

May. And that investment, had you held it, would be $4 million—until last week.

So how much of this short-

versus long-term thinking?

Well, long term we’re going to have to eventually move

landward and upward, because sea level is rising. And so if sea level rises two

more feet, you are going to have to go to the house at low tide, unless they

raise everything up, but that’s going to take a lot of dirt.

This is the fourth in a series of interviews on the effects of Sandy.

Part 1: Hurricane Researcher Brian McNoldy on the Science Behind Sandy

Part 2: Andrew Revkin on the Lessons Learned From Sandy

Part 3: Dr. Ralph Ternier Talks From Haiti About Sandy and Cholera

—Joe Spring