Blood in the Water

On December 24, 2009, a 6,600-pound orca killed trainer Alexis Martínez at a marine park in the Canary Islands. Two months later, trainer Dawn Brancheau was killed by an orca at SeaWorld Orlando. With the OSHA trial on trainer safety at SeaWorld Orlando starting September 19, Tim Zimmermann asks: Should Martínez’s death have served as a warning about the lethal potential of killer whales being trained for our entertainment?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

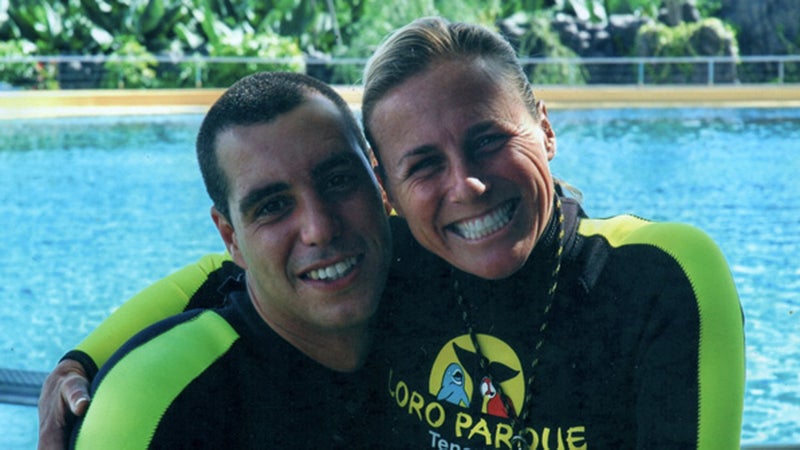

At 11:25 A.M. on December 24, 2009, Estefanía Luis Rodriguez’s cell phone rang. Rodriguez, 25, is an earnest, friendly young woman who works as a pharmacy technician near the coastal town of Puerto de la Cruz, on the north coast of Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands. She glanced at the caller ID and saw that it was her fiancé, Alexis Martínez, a killer whale trainer at a nearby zoological park called , one of the largest tourist attractions in the islands. Loro Parque displays everything from birds and dolphins to sea lions and, as of 2006, four orcas it had been loaned by SeaWorld.

Rodriguez and Martínez, 29, had been together seven years, after meeting at a friend’s party, and had moved into an apartment together three months earlier. She adored Martínez, who was handsome, generous, funny, and, in his spare time, played guitar in a band, Inerte. He’d been working nonstop with the killer whales at Loro Parque’s Orca Ocean to prepare for a special Christmas show.

When Rodriguez answered, however, it wasn’t Martínez on the phone. The caller was Orca Ocean supervisor Miguel Diaz, using Martínez’s phone. He told Rodriguez that Martínez had been involved in an incident with a killer whale but that he would be fine, that he was being taken to the University Hospital in San Cristóbal de La Laguna, about 20 miles away. Rodriguez immediately called Martínez’s family and then joined his mother, Mercedes, to rush to the hospital.

In the car, Rodriguez was deeply apprehensive. For months, Martínez had been telling her that all was not well at Orca Ocean, that there was a lot of aggression between the killer whales and that they sometimes refused to obey commands, disrupting training and the shows. After starting in Loro Parque’s penguin and dolphin displays, Martínez had begun as a killer whale trainer in 2006. As he gained experience, according to Rodriguez, he began to fret about safety, and he twice contemplated leaving the job. Preparing for the Christmas show only added to the stress. “I’m so tired,” Rodriguez recalls Martínez telling her. “That’s OK, everyone is tired from work,” she’d responded. He shook his head. “My job is especially risky, and I really need to be well rested and ready. With everything that is going on, something could happen at any time.”

On the road to La Laguna, Rodriguez and Mercedes worked their cell phones, and their sense of foreboding increased. Mercedes’s brothers and others had heard that Martínez wasn’t at the hospital at La Laguna but at Bellevue, the local hospital in Puerto de la Cruz, five minutes from Rodriguez and Martínez’s apartment. Confused, Rodriguez called Miguel Diaz. He again said that Martínez was at the hospital in La Laguna, but a short while later he called Rodriguez back to confirm that Martínez was at Bellevue. When Rodriguez and Mercedes finally arrived at Bellevue—at around 12:30 p.m., after about an hour of errant driving—they found Wolfgang Kiessling, Loro Parque’s president, already there, along with legal representation.

It was at Bellevue that Rodriguez and Mercedes learned that Martínez had, in fact, been killed, by an orca called Keto, during a training session. Rodriguez was in a state of shock, overwhelmed by sorrow and disbelief. Martínez’s body had been wrapped tightly in a shroud, and only his head and face were visible. Rodriguez says that no one from Loro Parque would tell her much, except that there had been an accident and Martínez had drowned. In the days and weeks that followed, she asked Martínez’s fellow trainers for more information, but she says they offered only evasive answers. Not until months later, when Rodriguez and the Martínez family learned the details of the autopsy, did they become aware of the full extent of the trauma and bite marks Martínez had sustained, suggesting a much more violent incident.

Rodriguez believes that Martínez’s death had been obscured and covered up. Keto’s attack on Martínez occurred at 10:25 a.m. Diaz called Rodriguez an hour later, and the autopsy report gives an estimated time of death of 11:35 a.m. “They had time to talk and prepare the body,” Rodriguez says of the more than two hours that passed between the incident and her arrival at the right hospital.

I asked Patricia Delponti, director of communications and public relations at Loro Parque, about the incorrect information Diaz had given Rodriguez. “As soon as the accident took place, we called his family’s home but got no answer,” she explained in an e-mail. “Therefore, we took Alexis’s mobile phone and called his girlfriend, whose number was in the address book. This call was made right after Alexis was taken to the hospital by emergency services.”

Delponti added, “This was a very difficult time for everyone, and if incorrect information was shared with those closest to Alexis in the time immediately following the accident, it can fairly be attributed to the nature of an emergency response.”

Rodriguez is skeptical. “Everyone in the family felt lied to,” she says.

The death of Alexis Martínez was a quiet tragedy for his family and loved ones. It received little media attention, even on Tenerife. The Martínez family received a life-insurance payout from Loro Parque and looked into the possibility of suing over Martínez’s death, but they were told by lawyers that Canary Islands law favored a large corporate entity like Loro Parque. Canary Islands authorities (including the police and the Ministry of Work and Immigration) also investigated the incident; there have been no major repercussions.

But exactly two months after Martínez was killed, on February 24, 2010, 40-year-old Dawn Brancheau, a skilled senior trainer working at SeaWorld Orlando, in Florida, was killed with similar violence by SeaWorld’s largest orca, Tilikum. This time the world noticed, and the media jumped all over the story. SeaWorld suspended orca-show routines that put trainers in the pools with its killer whales—a SeaWorld specialty known as water work—at all three of its locations, in San Diego, Orlando, and San Antonio, to conduct a safety review. That suspension remains in place, and SeaWorld’s new orca show, One Ocean, is performed without trainers in the water.

I wrote about the death of Brancheau, and the life of Tilikum, in a July 2010 ���ϳԹ��� story called “The Killer in the Pool”. At the time, I’d heard that another trainer had died just before Brancheau, at a park in the Canary Islands. But I could find almost no information aside from a brief news article. As details of the Brancheau story emerged, though, what happened at Loro Parque began to seem increasingly important—a stark warning about the unpredictability and lethal potential of killer whales being kept at marine parks for our entertainment.

Tilikum had been involved in two previous deaths, and SeaWorld’s trainers were prohibited from getting in the pool with him. That he managed to kill again—he grabbed Brancheau from a shallow pool ledge and yanked her into the water—was tragic, though not necessarily shocking. But Keto, the whale who killed Martínez and is also owned by SeaWorld, was cleared for routine water work. If Keto could kill, I wondered, how could any marine park orca be considered truly safe?

If Keto could kill, I wondered, how could any marine park orca be considered truly safe?

That question is at the heart of a between SeaWorld and the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the federal agency that oversees workplace safety. OSHA investigated Brancheau’s death and for failing to protect trainers “from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm.” In addition, OSHA said SeaWorld had willfully ignored the dangers of working with killer whales. “SeaWorld recognized the inherent risk of allowing trainers to interact with potentially dangerous animals,” Cindy Coe, OSHA’s regional administrator in Atlanta, said in an August 23, 2010, . “Nonetheless, it required its employees to work within the pool walls, on ledges and on shelves where they were subject to dangerous behavior by the animals.”

OSHA levied $75,000 in fines against SeaWorld—a small amount for a company that reportedly earned $1.2 billion in revenues in 2010. But OSHA’s stipulations on safety, conveyed in a document titled “Citation and Notification of Penalty,” could have dramatic implications for SeaWorld’s future. The citation is directed against SeaWorld Orlando and stipulates that to create a safe work environment, the park must either end water work and “dry work”—when trainers work with killer whales from the stage or on shallow poolside ledges—or adopt significant new safety measures, such as placing physical barriers between trainers and killer whales. If made, such changes—which presumably would be adopted at all SeaWorld’s parks—would fundamentally alter the nature of SeaWorld’s crowd-thrilling water-work shows, in which trainers swim with and ride the killer whales, sometimes even launching into the air from their noses.

Brancheau was the first SeaWorld trainer to be killed by an orca, after more than four decades of killer whale shows at the parks. (Though, as I learned while reporting “The Killer in the Pool,” during that same period dozens of trainers had been involved in serious incidents with killer whales, a number requiring hospitalization.) Naturally, SeaWorld was not happy about OSHA’s charge that it knowingly subjected trainers to undue risk, nor with the agency’s demand that it adopt intrusive safety measures. The marine park flatly rejected OSHA’s conclusions, arguing in a that they were “unfounded” and that OSHA’s “allegations in this citation are unsupported by any evidence or precedent and reflect a fundamental lack of understanding of the safety requirements associated with marine mammal care.”

The dispute comes to a head this September, when SeaWorld’s appeal of OSHA’s findings will be heard before a federal administrative-law judge of the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, an independent agency that adjudicates and issues written decisions when OSHA rulings are challenged.

SeaWorld’s rebuttal to OSHA pointed me back toward Alexis Martínez and Loro Parque. Martínez died just two months before Brancheau. Was his death a stand-alone tragedy, or was it relevant to the wider debate between OSHA and SeaWorld about the safety and future of killer whale entertainment?

As I learned, SeaWorld was a key partner in the launch of the orca program at Loro Parque, loaning the park four killer whales to help it start Orca Ocean. SeaWorld’s vice president of communications Fred Jacobs explained it to me this way in an e-mail: “Loro Parque is a highly respected zoological institution, and we have worked with them for years. The relationship was conceived primarily as a breeding loan and to allow Loro Parque to showcase these remarkable animals.” He added, “The deal differed only in scale from the dozens of similar partnerships we are part of at any given time. The addition of Orca Ocean, a facility that is comparable in size and sophistication to anything found in the U.S., also provided us greater flexibility in managing our collection of killer whales.”

At the time the loan was announced in December 2005, Jacobs publicly said there was a “financial arrangement,” but he declined to give details. What’s clear is this: SeaWorld would be deeply involved in managing its killer whales from the moment they arrived in February 2006. SeaWorld personnel oversaw their care and training at Loro Parque, and Brian Rokeach, a senior trainer from SeaWorld San Diego, supervised the training session in which Martínez died. To the extent that his death might be considered a precedent for what happened to Brancheau or evidence that working with killer whales in marine parks is risky and potentially lethal, SeaWorld was intimately aware of the details.

I asked Jacobs if Martínez’s death should be considered relevant to OSHA’s conclusions regarding SeaWorld and trainer safety. “Loro Parque is an independent and highly respected zoological institution with its own protocols,” he responded. “Because it is in the Canary Islands, however, it is not subject to OSHA. Because we are contesting OSHA’s citations, we are unable to discuss it further, except to reiterate that their allegations reflect a fundamental lack of understanding of the safety requirements of caring for these animals.”

SeaWorld and Loro Parque were somewhat responsive to my initial inquiries for comment for this story, but they repeatedly declined requests for interviews with the trainers and personnel directly involved in the tragedy, citing the OSHA litigation. Nevertheless, what emerged from extensive reporting and detailed information from confidential documents related to the incident is a case study of the knife edge on which orca trainers work, how easy it is for a killer whale to suddenly go rogue, and how difficult it is to help a trainer in the water once an orca decides to attack.

Finding out what goes on behind the scenes at a marine park is surprisingly difficult. In my experience, SeaWorld officials are selective about allowing media access to their current trainers. Many of their former trainers still work in the marine-park industry, where SeaWorld has enormous influence, or are reluctant to speak openly about their work. The fact that Loro Parque is on a Spanish island closer to Africa than to North America didn’t make things easier. Last summer, however, Naomi Rose, a senior marine-mammal scientist with , connected me with a former contract employee at Orca Ocean, Suzanne Allee. Allee worked there from February 2006 until July 2009, leaving about six months before Martínez was killed.

A 42-year-old Texas native, Allee ran the audio-visual department at Orca Ocean; during shows, from a booth above the main pool, she orchestrated music and video elements to sync with the sequences being performed by the whales and trainers. I met her last October, when she was in Washington, D.C., to meet with government agencies—including the National Marine Fisheries Service and the Marine Mammal Commission—involved in the export and care of killer whales in marine parks. She hadn’t intended to speak out about Loro Parque after her contract with the park ended, but when Martínez died she decided she wanted government officials to understand what was happening there, and she wrote a detailed report about what she’d observed.

Allee now lives near San Antonio and works as an independent filmmaker and screenwriter. In 2005, she was working on a seasonal contract in the entertainment department at SeaWorld San Antonio when she heard that SeaWorld was striking up a partnership with Loro Parque to launch Orca Ocean. A completely new facility of pools—to be filled with millions of gallons of seawater pumped in from the Atlantic Ocean—was being built. A full-time contract on an exotic island sounded attractive.

Allee arrived at Orca Ocean on February 13, 2006, a day before SeaWorld’s four killer whales were flown in on a wide-body transport plane. Keto (a ten-year-old male) and Tekoa (a five-year-old male) came from SeaWorld San Antonio. Kohana (a three-year-old female) and Skyla (a two-year-old female) came from SeaWorld Orlando. Killer whales are highly intelligent, social animals, and adapting to a new environment and social order is always tricky. Both the young females, who were expected to breed as they matured, were separated from their mothers for the move. And Keto, who was born at SeaWorld Orlando, was headed to his fourth marine park in seven years. (For more details on the lives of captive orcas compared with those in the wild, see “The Killer in the Pool”.) Thad Lacinak, then SeaWorld’s vice president and corporate curator for animal training, had flown in to release the whales into their new home. Mark Galan, a senior trainer from SeaWorld Orlando, was also there to receive the killer whales and would supervise their care and training for the next 18 months.

To help get Orca Ocean going, SeaWorld had trained a group of Loro Parque killer whale trainers at its San Antonio and Orlando parks. After it opened, SeaWorld senior veterinarian James McBain made regular visits, and SeaWorld vets held biweekly conference calls with Loro Parque’s trainers to talk about the health of the animals. SeaWorld was able to monitor its whales remotely through the Orca Ocean’s video surveillance system, and SeaWorld’s chief zoological officer, Brad Andrews, made a practice of flying in at least twice a year to make assessments.

When the assigned SeaWorld supervisor was away for any reason, SeaWorld would rotate in a temporary replacement. In September 2006, Dawn Brancheau pulled a temporary rotation at Loro Parque, arriving to fill in for Mark Galan. According to Allee, Brancheau’s skill and artistry in the water with the whales impressed the Loro Parque team. Brancheau also became close to Martínez. After his death, Estafanía Rodriguez says, “Dawn was the only person who really showed her feelings about Alexis. When she died, we had to relive everything again.”

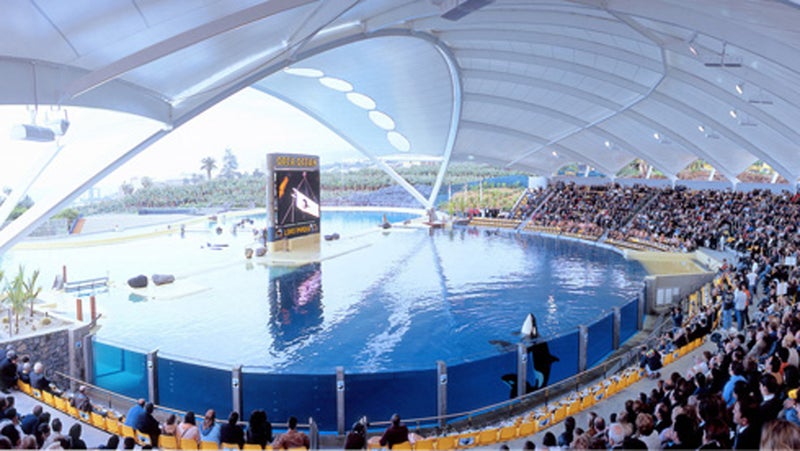

As Allee strolled through Loro Parque for the first time, she thought Orca Ocean looked like it would be a spectacular facility, with a couple of back pools and a medical pool fronted by a large stadium pool with a main stage and a huge video screen. It was all set against a lush tropical background, with picturesque views of the ocean. Before long, however, Allee started to wonder if Orca Ocean was ready for prime time. The tone was set when the whales first arrived: as Keto was craned toward the pool, the hammock he rode in started to split while still suspended over the concrete deck. “There was a mad dash to get him back into the [transport] water tank before he splatted all over the place,” Allee recalls. The next three-plus years at Orca Ocean only intensified her concerns. “They didn’t have a clue about what it took to run an orca operation,” she says.

Asked about Allee’s concerns, Loro Parque’s Delponti argues that Allee isn’t in a position to make such judgments because she’s not a trained whale expert. “It should be noted that Allee’s time at Loro Parque never involved training, caring for, or interpreting the animals that live there,” Delponti e-mailed me. “She was an audiovisual technician working under contract. We have been caring for and displaying marine mammals for many years. Our staff is highly respected and well trained. We worked with SeaWorld on every aspect of this program.”

Orca Ocean officially opened on February 17, 2006, with a gala celebration attended by Loro Parque president Wolfgang Kiessling; August Busch III, then chairman of Anheuser-Busch InBev (which at the time owned SeaWorld); and Adán Martin, then president of the Canary Islands. The opening had originally been scheduled for December 17, 2005, Loro Parque’s 33rd anniversary, but construction on the pools had fallen behind. After the opening celebration, the complex was shut down for four weeks so that electrical work and other final touches could be completed and, Delponti says, so that the recently arrived whales could acclimate to the pools.

The first show open to the general public took place on March 17, 2006, but there were problems with the new pools. They had been coated with a product called Metflex, which hadn’t adhered properly. (Metflex and Loro Parque both lay the blame on the other.) And that, in turn, led to orca problems. Killer whales, the largest members of the dolphin family, have sophisticated sonar and an ability to locate and exploit any flaws in their pools. They also have a proclivity for seeking out any possible diversion in the relatively barren marine-park environment. Keto, Tekoa, Skyla, and Kohana quickly developed the habit of using their teeth to peel away strips of Metflex from the pool walls, like bored kids picking at loose paint.

One week after the opening, Allee says, while a packed stadium awaited, all four whales appeared in the backstage area with strips of Metflex hanging from their mouths and pool paint smeared across their rostrums, or snouts. Trainers rushed to wipe away the paint with isopropyl alcohol. When the whales were finally released into the show pool, they ignored the trainers and went back to nibbling. The show was a mess. Once again, Orca Ocean was shut down for repairs, this time for ten weeks.

Even after the repairs, Metflex strips would show up in the pool skimmers, and the killer whales continued to pick at it and ingest it. Toward the end of 2006, Keto, Skyla, and Kohana underwent endoscopies to examine their gastrointestinal tracts. Endoscopy on a killer whale requires raising the animal up out of the water using a medical pool’s lifting floor. While trainers try to restrain the whale, a wooden bit is inserted into its mouth and a flexible tube with a camera snaked down through the bit to examine the digestive system. Allee documented the procedures on video. This clip shows key moments during an endoscopy that Keto underwent in November 2006.

When asked about the procedures, Delponti told me: “Endoscopy is a routine diagnostic procedure used if veterinary professionals suspect the ingestion of a foreign object. Such events are rare, and all animals living at Loro Parque are in excellent health today.” (Eventually, Loro Parque replaced the Metflex with a different pool coating.)

The four Loro Parque killer whales also struggled to adapt to one another. In the wild, most killer whales live in family groupings, or pods, with a well-organized matriarchal structure. Keto, Skyla, Kohana, and Tekoa were all bred and born in marine parks, but they had been removed from their established social structures at SeaWorld San Antonio and SeaWorld Orlando. Without the ties of family or language, marine park whales have to sort out an ad hoc social pecking order, often through bullying and aggression, which sometimes results in a relatively stable grouping and sometimes not. The social structure was likely complicated at Loro Parque because there was no mature and clearly dominant female to establish order.

During her time at Loro Parque, Allee documented some of the injuries that resulted from whale aggression. This picture shows Kohana in October 2006, after Keto bit her dorsal fin.

I asked Delponti about the killer whales’ social structure and about any aggression, such as raking, ramming, and biting, they might have exhibited toward one another at Orca Ocean. She responded that the whales are a stable group. “Killer whales are social animals and any group of these animals, whether in the wild or in a facility like Orca Ocean, works out their own social structure, including dominance hierarchy,” she wrote, adding that “bumping and raking … expressions are entirely normal in any social species” and that “any injury or illness in our animals is promptly and professionally treated.”

Alexis Martínez also paid close attention to the social structure and behavior of the whales. Like any good trainer, he knew that the better he got to know each whale—its moods, its predilections, its likes and dislikes—the safer and more effective he would be. He kept notes in journals, recording how the whales interacted with one another and how they behaved during training and shows. Between June and October 2009, Martínez focused his entries on Kohana—who would undergo an ultrasound in August to determine if she was pregnant—and made reference to her frequent slowness in practice and training, as well as her frequent unhappy vocalizations. “Bad vocals in Pool A (alone),” Martínez noted in June. “Back to feeling insecure when separated, alone, both in shows & in sessions.” In late September, he noted that Kohana’s vocalizations and attitude had improved but that she “always has rises & falls in temperament (unstable).”

In August, he summarized the complicated sexual dynamics in the pools, which also affected the stability of the killer whale grouping. “Keto is obsessed with controlling Kohana, he won’t separate from her, including shows,” he wrote. “Tekoa is very sexual when he is alone with Kohana (penis out). Keto is sexual with Tekoa.” On September 2, 2009, without elaborating, he noted that “Brian [Rokeach, SeaWorld’s supervising trainer at Loro Parque at the time] had a small incident with Keto the first hour of the morning,” and that it was “a very bad day for Keto.” On September 12, he wrote, “All the animals are bad. Dry day for Kohana.”

������’s a video of Martínez performing with Kohana in spring of 2009.

Sometimes the charged dynamic between the whales would get a very public airing. During one show that Allee was working in the summer of 2007, Tekoa was performing when Keto raced into the show pool, rammed him, and then proceeded to chase him. After the trainers regained control, they completed the performance with Tekoa, even though blood was visibly seeping from his wounds. His final display of behavior was a full-body pose on the main stage. “The last image the audience saw was the stage covered in Tekoa’s blood,” Allee recalls.

Allee had seen intra-whale conflict during her work at SeaWorld San Antonio, but the dynamic at Loro Parque seemed different. “I never saw so many instances in which the animals were out of control or beating up on each other,” she told me. “There were lots of shows I directed where the trainers did not do water work or have control of the animals.”

It's impossible to know how the challenge of adapting to a new life in Loro Parque’s pools increased any potential danger the trainers faced. But two years before Keto killed Martínez, Loro Parque almost lost a female trainer, 29-year-old Claudia Vollhardt, to an attack by Tekoa. In October 2007, Vollhardt was working a training session with Tekoa, who weighed about 3,000 pounds at the time, under the supervision of SeaWorld senior trainer Steve Aibel—who was .

When killer whales perform a behavior correctly, they are “bridged” (often with a whistle sound, in essence signaling “well done”) and then receive reinforcement in the form of a reward, such as a fish or a playful rubdown. When they don’t perform correctly, the trainer reacts with a three-second neutral response and withholds the reward. This is known as a least-reinforcing scenario, or LRS. Repeated failed attempts—and the corresponding lack of reward—can sometimes lead to a frustrated killer whale. “The question the trainer has to constantly be asking is: Is this animal mildly frustrated but still has the ability to stay with it and work through the problem?” explains Samantha Berg, who worked as a trainer at SeaWorld Orlando’s Shamu Stadium in the early 1990s. “Or have I gone beyond this animal’s limits and it’s time to cut the losses, take a break, and start over?”

Vollhardt, who had transferred to Orca Ocean from the Loro Parque dolphinarium, was having trouble practicing a foot push, a behavior in which the killer whale presses its rostrum against the trainer’s foot and propels the trainer across the pool, either underwater or above the surface. After a few failed attempts, Tekoa grabbed Vollhardt’s arm and took her to the bottom of the pool. He then dragged her toward the steel gate between the show pool and the back pools and began banging her against it.

Allee was in the trainers’ office when she heard the emergency siren go off, and she ran out to a chaotic scene. Aibel was crouching by the trough, yelling for the Orca Ocean staff to get a net in the pool. (The whales are taught to retreat when a net is dropped into the water and pulled across the pool.) When Tekoa let Vollhardt go for a moment, Aibel managed to haul her up onto the pool deck. He immediately began CPR and yelled for someone to call an ambulance, even as Tekoa continued to try to reach Vollhardt as she lay by the side of the pool. Vollhardt was carried into a nearby office, where her wetsuit, covered in bite marks and blood, was cut away, and then rushed by ambulance to the intensive-care unit of the hospital in La Laguna. She eventually recovered, after surgery on her lacerated and broken arm.

“Claudia is an experienced marine biologist and marine mammal professional,” Delponti wrote to me when I inquired about this incident. “She was conducting herself appropriately on that day. Our response protocol worked properly and we are gratified that she made a full recovery. To this day, she works by her own wish in Orca Ocean.”

In a media release, Loro Parque described the incident as an accident caused by bad luck. But both Loro Parque and SeaWorld conducted a post-incident safety assessment, which led to improved emergency-response measures, including installing an onsite defibrillator. According to Allee and Rodriguez, Orca Ocean trainers stopped water work for more than six months. In addition, special protocols were enacted for Tekoa, and restrictions were placed on working with him in the water. “Our protocols are continuously evaluated and we seek to learn from incidents like this and improve our techniques and equipment,” Delponti wrote.

Skyla has shown signs of unpredictability, too. In the spring of 2009, during a public show, she started pushing her trainer around the pool and up against the pool wall. Shortly thereafter, special protocols—limits on water work and a mandate that only senior trainers work with her, according to Allee—were enacted for Skyla as well. Out of the four SeaWorld killer whales at Loro Parque, only Keto and Kohana were now considered fully suitable for routine water work.

Following Tekoa's attack on Vollhardt, Rodriguez says, Martínez told her about the unpredictability of the whales and how they often banged on the gates between the pools. He said he saw plenty of small incidents that he worried could easily have turned dangerous. Everyone at Orca Ocean treated this behavior as normal, he explained to her.

Martínez loved working with killer whales. Over time, though, according to Rodriguez, the excitement and allure of working at Orca Ocean started to fade for him. The pay just wasn’t worth the risks and the exhausting work, he told her. But in 2009, with Christmas approaching, Martínez was selected to perform in the holiday show, alongside SeaWorld San Diego’s Brian Rokeach. On the fatal day, December 24, Martínez and Rokeach, along with five other Orca Ocean trainers, ran through a morning practice session with Keto, who worked alone in the show pool while the other three killer whales were secured in the two back pools.

As noted, SeaWorld and Loro Parque declined to make anyone with direct knowledge of the incident available for comment. But marine parks investigate and create formal reports after serious incidents, and there is a confidential corporate-incident report, dated December 30, 2009, that tells the story of Martínez’s death. I learned the details contained in it, but when I asked SeaWorld’s Fred Jacobs and Loro Parque’s Patricia Delponti for comment, they declined to offer any, citing the OSHA litigation, and added that they would no longer be communicating with me or ���ϳԹ��� about the story. (Jacobs also stated that there were errors in my reporting but declined to specify them or offer any corrections.) What follows, as a result, is based on the details of the corporate-incident report.

According to the report, which was written in Spanish, Keto “appeared in a good mood” that day and had behaved well during routine animal care and a swim session with Skyla. However, the report notes that Keto often showed more interest in what was going on with the other whales than in working alone in the show pool. It also alludes to a September 2, 2009, incident—presumably the same incident with Rokeach that Martínez mentioned in his journal—and says Keto was emitting vocals during a perimeter ride and then left “control” and took off, swimming fast around the pool and bowing (porpoising in an agitated manner) after the trainer who’d been riding him had hopped off.

During the fatal session, Rokeach worked from the show pool’s main stage, Martínez joined Keto in the water, and the other Loro Parque trainers were at different locations around the pool. According to the report, Keto started off well, but then Martínez tried a behavior called a stand-on spy hop, in which he stood on Keto’s rostrum as Keto drove his body vertically up and out of the water. Keto had good power but was leaning slightly as he rose from the surface, and Martínez fell off. Because the stunt had not been executed cleanly, Keto was not bridged.

Keto took a quick breath, returned to Martínez, and then came back to the surface carrying Martínez’ limp body across his rostrum.

A short time later, Martínez initiated another spy hop. Again, Keto came up twisting, and this time Martínez responded with an LRS. To help get Keto back on track, he was called to a shallow ledge across the pool from the main stage, and when he obeyed another trainer rewarded him with two handfuls of fish. Keto, according to the report, seemed calm. Martínez then told Rokeach and the others that he was going to ride Keto down into the pool and up onto the stage, a sequence called a haul-down into stage haul-out.

On the way down Keto went too deep, and as he approached the bottom of the 12-meter pool Martínez abandoned the haul-out and asked Keto to follow his hand with his rostrum. Together they drifted up to the surface, and again Martínez responded to Keto’s failure with an LRS.

This time, though, Keto responded oddly. According to the incident report, “Keto surfaced with Alexis and seemed calm, but appeared to position himself between Alexis and the stage. Alexis waited for calm from Keto and requested a stage call via underwater tone.” Keto responded and swam over to Rokeach, who was standing on the stage. But Rokeach observed that Keto appeared “not committed to remaining under control” and a little “big-eyed.” Instead of walking back to get a fish bucket, Rokeach asked another trainer to bring it to him. Like Martínez, Rokeach gave Keto a hand target to focus him, one of the simplest and first behaviors most marine-park killer whales learn. When Rokeach felt Keto was under better control, he asked Martínez, who had been waiting patiently near the center of the pool, to swim slowly toward the slide-over (a ramp connecting the show pool to the back pools) at the edge of the main stage so he could get out of the water. Notably, the incident report makes no mention of Rokeach feeding Keto any fish.

As Martínez started to paddle gently through the water, the report indicates, Keto took note and started to lean in his direction. Sensing he was about to lose control, Rokeach gave Keto another hand target. This time Keto ignored it. He went after Martínez, driving him to the bottom of the pool with his nose. (In his testimony to Canary Islands’ investigators, Orca Ocean assistant supervisor Rafael Sanchez said, “The animal in question moved towards him and hit him and violently played with his body.”)

Loro Parque issued a statement saying Martínez’s death was an “unfortunate accident” and that he had likely died due to asphyxiation resulting from compression of his chest.

Rokeach and the other trainers did what they could, but a powerful 6,600-pound killer whale is the master of his domain. Rokeach slapped the water and banged the bucket on the stage, both signals for Keto to return. He slapped the water again, and this time Keto responded, leaving Martínez at the bottom of the pool—Martínez had been under an estimated 30 seconds by then—and surfacing without him. Rokeach sounded the emergency alarm. Keto took a quick breath, returned to Martínez, and then came back to the surface carrying Martínez’ limp body across his rostrum. Rokeach called for the team to get a net in the water while others raced to corral the other three killer whales into one of the back pools. It took almost two minutes to get Keto out of the show pool and secure the gate between the pools (Keto slowed the process by about a minute by interfering with the gate as trainers tried to close it).

By this point, Martínez—apart from the brief moment Keto brought him to the surface—had been on the bottom of the pool for almost 3 minutes. Rokeach and another trainer dove in and resurfaced with Martínez, who was unconscious and had blood coming from his nose and mouth. A distraught Rokeach immediately initiated CPR. A defibrillator was brought out, and Loro Parque called for an ambulance. But Martínez was never revived.

Loro Parque issued a statement saying Martínez’s death was an “unfortunate accident” and that he had likely died due to asphyxiation resulting from compression of his chest. “After completing the [exercise],” the statement said, “Alexis was knocked by the orca in an unexpected reaction of the animal,” adding that “the study of the facts shows that the animal’s behavior did not correspond to the way in which these marine mammals attack their prey in the wild, but was rather a shifting of position.”

But as with Dawn Brancheau, the autopsy report on Martínez was telling and states bluntly that his was a “violent death.” It describes multiple cuts and bruises, the collapse of both lungs, fractures of the ribs and sternum, a lacerated liver, severely damaged vital organs, and puncture marks “consistent with the teeth of an orca.” It concludes that the immediate cause of death was fluid in the lungs (i.e., drowning) but that the fundamental cause was “mechanical asphyxiation due to compression and crushing of the thoracic abdomen with injuries to the vital organs.”

In other words, at some point Keto probably slammed into Martínez with such force that he caved in his chest.

So what drives an animal in captivity to snap? SeaWorld and Loro Parque maintain profiles of their killer whales, which, in addition to history, physical characteristics, and health notes, include tendencies and personality observations. These profiles are closely guarded, but I managed to learn some of the details used to help trainers understand Keto.

Keto’s profile indicates that before he moved to Loro Parque in 2006, he disliked major environmental changes and occasionally struggled with prolonged separations from other whales. In the “aggressive tendencies” section, the profile notes that Keto would sometimes become vocal, ignore bridges, and perform behaviors incorrectly in advance of getting aggressive. On a few occasions during his time at SeaWorld’s parks, the profile shows, Keto either came at a trainer with his mouth open, mouthed trainers’ feet, or, in one incident, mouthed a trainer’s leg. None of the incidents, according to the profile, resulted in injury.

As Keto matured, the profile indicates, he developed into a fairly reliable water-work killer whale. It notes, however, that Keto’s reliability was influenced by the social structure of the whales in his group and that he could be inconsistent when there was social unrest or sexual activity. At SeaWorld San Antonio, the profile notes, SeaWorld management took the precaution of avoiding water work with Keto when Kayla (a female killer whale Keto was interested in) was together with Ky (another male whale).

To further explore what might have set Keto off, I asked four former SeaWorld trainers to analyze Martínez’s interaction with him. They all cautioned that the judgments a trainer has to make in the water are highly subjective. “A trainer applying what works for one whale could have completely different consequences during an interaction with another whale,” says Carol Ray, who worked at SeaWorld Orlando from 1987 to December 1990.

Based on the information I shared with them about the incident, no one saw an obvious error or catastrophic decision. However, they did focus on a few facts: that Keto executed a succession of high-energy behaviors that did not earn him a bridge or any fish, that Keto was switched between a number of trainers during the session, and that Rokeach had asked Martínez to swim out before giving Keto any primary reinforcement (fish) after coming to the stage.

Internally, I learned, SeaWorld personnel would focus on Rokeach’s decision to direct Martínez to the slide-over (which was the quickest way out but also brought him closer to the stage and to Keto) instead of having him exit from the other side of the pool. Rokeach’s decision to ask Martínez to swim out before feeding Keto fish at the stage—possibly establishing better control—also drew scrutiny. (I repeatedly tried to reach Rokeach, directly and via SeaWorld, to get his take on the incident but never got a response.)

What I took away was this: given the subjectivity and complexity of the interaction between a human and a killer whale in a marine-park pool, it seems unlikely that any trainer can make the right decision each and every time. As former SeaWorld trainer Samantha Berg puts it, “Things are happening on so many different levels that any assertion that it’s possible to control all the variables is absolutely ludicrous. And you can bet the whales were often frustrated when trainers did something that didn’t make sense to them.”

A frustrated killer whale—whether it’s struggling with captivity, social structure, sexual tension, poor health, or training failures—is a potentially dangerous killer whale.

A frustrated killer whale—whether it’s struggling with captivity, social structure, sexual tension, poor health, or training failures—is a potentially dangerous killer whale. “This is not an issue with most whales most of the time,” says Ray. “But in cases like Keto, Alexis, and Brian, it might be enough [for Keto] to say, ‘Screw you! I did my effing best to haul your human ass out of the water the way you wanted me to—twice, dammit!’ Just as we should expect stress to get to any large, intelligent, confined animal with hormones who is trying to do the right thing for the people that control its food and life.”

The corporate incident report, in effect, acknowledges the imperfect understanding between man and whale. Regarding Keto’s killing of Martínez, the report drily concludes, “Behavior of the animal involved: unforeseen, incorrect.” “Incorrect” is a wholly inadequate description of what Keto did to Alexis Martínez. But it’s the “unforeseen” part that should make any trainer nervous. Keto had not been designated a dangerous whale, but he sent the message that no marine-park killer whale can ever truly be considered safe—and that no trainer in the water with one is ever truly free from risk.

Since Martínez’s death, Orca Ocean has not resumed full water work with its mature killer whales. Three of the four orcas it received from SeaWorld—Keto, Tekoa, and Skyla—now have a history of incidents. Meanwhile, Kohana gave birth to her first calf, Adán, in late 2010. For its part, SeaWorld briefly ceased water work at its three parks in the immediate aftermath of Martínez’s death as it tried to get details about what happened. But within a week, water work was under way again at all of them. It continued for almost two months, until Dawn Brancheau’s death prompted another suspension of water work, which remains in effect.

Still, SeaWorld has said that it would like to resume water work with its whales, and the park has been exploring the installation of fast-rising floors in some of its pools to quickly raise a whale and a trainer in trouble out of the water. Other safety measures that have been considered include personal air systems for trainers and the deployment of underwater vehicles that could distract the orcas in case of an emergency. That certainly suggests that SeaWorld understands there are inherent risks that arise when humans get in the water with one of the ocean’s most powerful and intelligent predators.

In the end, Martínez’s death offers the most compelling testimony possible on this point. In its report, the Canary Islands Ministry of Work and Immigration notes that the main risk is “precisely in the interaction with an animal that weighs more than three thousand kilos and is also in its natural environment (water).” The report concludes that Martínez was engaged in an “inherently risky activity” and that the only preventive action is a simple one: “prohibition of the activity.”

Ultimately, the question of whether performing in the water with killer whales at SeaWorld should be ended or severely constrained by safety measures will be decided by the OSHA proceedings. If, after the legal proceedings are resolved, water work becomes a distant memory for marine-park fans, that will be fine with Rodriguez. Martínez is never far from her mind, and his ashes are interred in a spot near their home, beneath the protective canopy of a Canary Islands Dragon Tree that overlooks the sea.

“If one demonstrates that there is no safety due to the unpredictable behavior of killer whales, this type of show should be ended,” she says. “Too many people have died, and this should not happen again.”