End of the Run

Two decades ago in Sarajevo, Bill Johnson won America's first Olympic gold medal in the downhill with an astonishing kamikaze performance. Now, in the wake of a comeback attempt that almost killed him, skiing's crash-course survivor struggles with the consequences of a life lived too fast.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

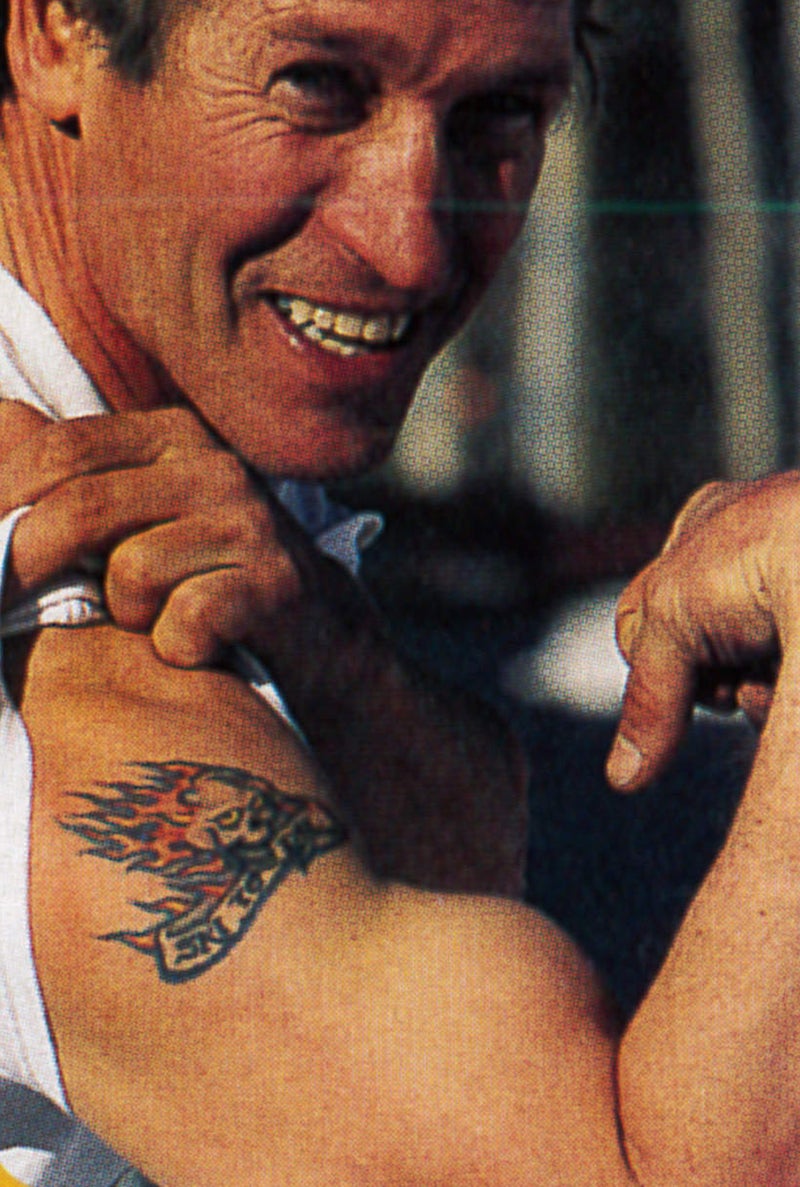

The house was empty and it would soon be demolished—wrecking balls and all that—so they decided to have one last party there, the real estate agent and her friends. It would be a white-trash theme party—the Corn Dog Hoedown. Guests showed up in cutoffs and gingham halter tops. A tattoo artist named Bill Conner laid out his needles on a table by the sliding-glass door overlooking the pool and waited. Conner had traveled here to San Diego all the way from Miami Beach, where he worked at Tattoo Circus, rendering Harley logos, pinup girls, whatever, for tourists. On this February night in 2000, he was doing tats for practically nothing.

Pretty soon along came this guy—muscular, intense, somewhat inebriated. He would get in a fistfight later that evening, after trying to hit on some marine's girlfriend. Conner remembers seeing him with a gash on the head, being escorted off the property. But right now all he wanted was a tattoo, an over-the-top number he'd thought of himself. “I drew up a little skull with flames coming out of it and a banner underneath with the words 'Ski to Die,'” Conner says. “He was stoked.”

Drunk-guy tattoos are often a source of serious regret, but not this time. The man who got it was an unrepentant speed demon, a former world-class skier who'd attained a brief flash of stardom, ages before.

On February 16, 1984, William Dean Johnson, then 23, won the men's downhill at the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia. On that cold afternoon he became the first American man in Olympic history to earn a gold medal in an alpine skiing event. Perhaps you remember his run: the hissing violence of his skis as he knifed through the tight turns on the upper half of the course, the wild looseness of his body flowing over the jumps, that ultratight tuck, and the euphoria with which ABC announcer Bob Beattie shouted, “Yes, he's done it! He's done it!”

The spectacle was even more poignant because Bill Johnson was a working-class kid, a onetime juvenile delinquent snatching victory in a sport long ruled by the rich. Johnson had grown up near Portland, Oregon, in the logging town of Brightwood, and his family was so strapped for cash that at times they had to sleep in the car when they traveled to ski races. As a kid, Bill broke into houses for kicks. He once stole a Chevy; he spent three days in jail.

He was brash, abrasive, and wholly surprising. When he arrived in Sarajevo, he wasn't even among the world's top ten downhillers. Yet the course—relatively straight and flat—was tailor-made for fast gliders like Johnson, and he saw this, cockily predicting, “Everyone else is here to fight for second place.” He backed it up, too, trouncing his closest competitor by 0.27 seconds. When one reporter asked about the value of his gold medal, he swaggered and said, “Millions. We're talking millions.”

He was not a bad guy, actually. He responded to all of the 50 or so fan letters he got each week, and after winning the gold he remained the consummate buddy to a tight band of friends, most of them skiers. “He's loyal to the death,” says retired U.S. Ski Team racer Mark Herhusky. “He's the kind of person you'd want on your side in a barroom scuffle.”

But Johnson's crash-and-burn style was better suited to the slopes than to daily life. He drove fast, partied hard, shot guns, surfed at midnight, and in general carried on as if those clichéd extreme-sport adages—Rip it! Tear shit up!—were his holy credo. In the end, the fire that propelled him, that youthful fearlessness, would devolve into a sort of desperation—nihilism, even. He would become the stereotypical ex-jock who destroys himself trying to act young, and his life would serve as proof that you cannot burn on forever. There he was at the white-trash party—unemployed, of no fixed address, in the midst of a divorce, and pathetically intent on reconnecting to his glorious past.

Ski to Die. Right after the ink dried on his shoulder, Johnson—who was about to turn 40—launched a long-shot bid to make the 2002 Olympic ski team. Almost no one has stayed on the team past 30. Johnson had retired from the World Cup circuit at 29 and had spent much of the past decade off skis, working as a freelance carpenter. He had herniated five disks and his shoulder was held together with pins, thanks to old ski-racing injuries. Without any sponsorship of note, he had only one pair of new skis instead of the five or six that elite racers typically need.

Nonetheless, last winter he began tooling around the West in his '84 Ford pickup—going to races and slowly climbing out of the basement of the national rankings. By March 2001, when it came time for the U.S. Alpine Championships at Big Mountain in Montana, Johnson was starting 33rd in a field of 63 racers. He hoped to triumph by skiing fast through an icy, rutted dogleg turn near the base. He hit the turn at 50 miles per hour. Then he caught an edge, his legs went spread-eagle, and his body flew sideways through the mesh fence marking the course. His helmeted head smacked the snow, hard; his brain rotated inside his skull, and tissue tore and bled. Within minutes he was in a coma.

It was early October, six months after the crash, and Johnson was sitting at the breakfast table inside his mother's home near Portland, puzzling over a legal form as the soft autumn light washed in through the window. He is five-foot-nine, with reddish blond hair, and he's still handsome in a ruddy, straightforward way. He'd gained 25 pounds and a slight paunch since his accident, though, and his movements were herky-jerky. He smiled, and it was a huge smile, simple and generous. I liked him.

“I have to fill this out,” Johnson said, “for the state.” I nodded, and then he said it again: “I have to fill this out for the state.”

Johnson's fall made his brain swell, putting pressure on his upper brain stem and triggering the coma. By the time medics arrived, his pupils weren't reacting to light. A chunk of his tongue had torn free and blood was filling his lungs. On the Glasgow coma scale, which ranges from three (no brain activity) to 15 (fully cognitive), Johnson was a five.

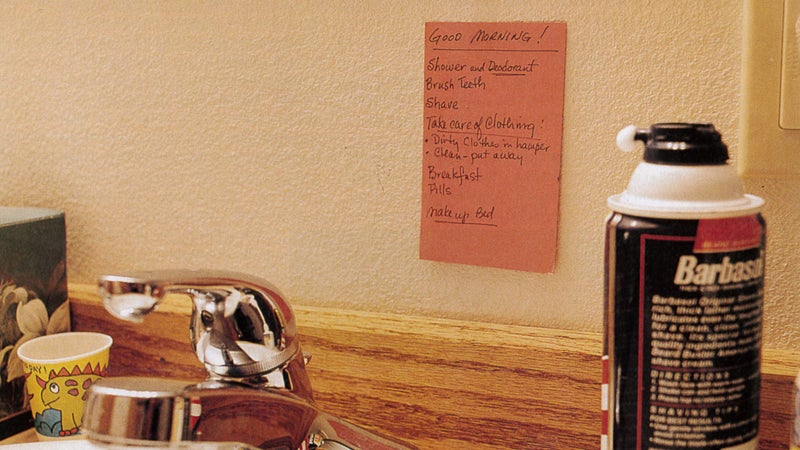

He was unconscious for more than three weeks, and when he came to it was like his brain, damaged by countless small tissue tears, was a computer whose wiring had frayed. He couldn't remember anything from the previous six years. He had to learn the most basic human activities—walking, speaking, brushing his teeth—all over again. After three months at the Centre for Neuro Skills in Bakersfield, California, Johnson returned to Portland to live with his mother, DB, and her second husband, Jimmy Cooper, a machinist. Johnson continued to visit various therapists four or five times a week, where he spent hours doing balance exercises and memorizing words. He had the emotional outlook of a child, and when he tried to talk, the phrases often floated loose in his mind.

“I forget where I crashed,” he said to me. “I think it was 1991, but people tell me I was 40 years old and that's amazing because I didn't want to make a comeback when I was 40 years old. It doesn't make any sense to me. But I want to get prepared for next year's racing. There's no way I can be on the U.S. Ski Team, the way my body is now, but next year…”

Johnson's mother was in the garage, where she runs a small business selling flags and banners for sporting events, but eventually she wandered into the room. DB Johnson is 65, sturdily built, with gray hair. She's brisk and upbeat in the manner of someone used to making the best of tough situations.

“Bill,” she said cheerfully, “tell him what you did yesterday.”

“Caught a 27-inch steelhead. It was no big deal. Normally I catch all the fish in the river.”

“And what else?”

“Went mountain biking. I fell a lot. I fell four or five times and my knees and elbows are scratched, but I made it six miles.”

Johnson was also playing golf; recently he'd shot a 38 for nine holes. His body, it seemed, remembered being an athlete. After months of therapy, however, his brain was still faltering. “I'd place his physical recovery in the upper third among brain-injury patients,” says his doctor, Molly Hoeflich, a physiatrist at Portland's Providence Medical Center, “but he will be left with permanent cognitive deficits. It's impossible to say how much, but people with brain injuries—they frequently have a hard time returning to work. They need to live in a supervised setting.”

Which means that, for the foreseeable future, Johnson will be staying with his mother. His therapy could go on for years, and the cost will be covered only partially by Johnson's insurance, so DB is having him file for bankruptcy to protect himself from mounting medical bills. Meanwhile, she will loyally shuttle him back and forth between therapists.

“We were prepared to walk him to the bathroom when he came home from Bakersfield,” DB told me. “This isn't scary. We just hope he comes out of it. It's hard. It's very difficult.” From the warmth of her words, it was clear that she loved the youngest of her four children and wanted to shield him from further hurt. If you ask too much, DB's crossed arms and hard glare seemed to tell me, I'll cut you off. She has always protected Bill—from the pain of her 1976 divorce from her first husband, Wally Johnson, and from the trouble that Bill never seemed able to escape both as a child and as a grown man. It was DB who lobbied principals to keep Bill in school despite his playground brawling. Later, in 1985, she quit her job so that she could travel the ski circuit and work as his agent, soliciting endorsements. Their relationship was at times contentious. In fact, they were enmeshed in a dispute over finances before Bill crashed. Even now he can get sour on her.

“I could live in this house forever,” he told me as I was leaving one day, “but do I want to? It's not a question.” He turned to his mother. “I don't want to live with you right now. It's just not part of my life.”

“Well, where do you want to live?” DB said, unfazed.

“Alone,” Bill said. He slumped in his chair and glowered.

Mark Herhusky flew to Montana immediately after the accident. He sat in Johnson's hospital room for five days, reading fan letters out loud. Other friends played Led Zeppelin and Stevie Ray Vaughn tapes, in hopes that the familiar tunes would jolt something deep in his memory. They stayed with him overnight, listening for a conscious moan, waiting for him to open his eyes. A guy who washed dishes with Johnson more than two decades ago recently launched the Bill Johnson Foundation, which has raised $6,000 toward Johnson's future living expenses. Clearly, the best thing that has happened in the wake of Johnson's crash is the great outpouring of support he's gotten from friends, from what former pro downhiller John Creel calls “the ski-racing brotherhood.” Creel, 45, is a firefighter who raced against Johnson in the seventies. Like Johnson, he is friendly and boisterous, with a testosterone-heavy résumé. He's a waterfall kayaker and was the first person to ski the crater of Mount St. Helens after it erupted in 1980. He entered Bill Johnson's story in the summer of 2000, when Johnson showed up at Creel's fire station, looking for someone to coach him through his comeback attempt.

“He walked in with an ice cream cone and ice cream dripping down his shirt, and he said he wanted my help,” Creel remembers. “We weren't close friends. It wasn't like we'd chased chicks together, but he was part of the brotherhood. I told him, 'Follow me home. We start training tomorrow.'”

Creel still styles himself as Johnson's coach. Though he acknowledges Dr. Hoeflich's assessment—that it's extremely unlikely Johnson will ski at a top level again—he's reluctant to let go of the notion that he's orchestrating an Olympic comeback. All last fall, as Johnson struggled with ordinary tasks, Creel shepherded him through a training regimen he described as “riding the edge.” It consisted largely of drinking beer, with a little golf and fishing thrown in. In late November, Johnson officially returned to the slopes with some mild runs at Mount Hood. The primary training camp was Creel's house in Maupin, Oregon, a tiny desert town on the Deschutes River, 100 miles east of Portland. One morning Johnson and I decided to head out there with fishing poles. He wore a special T-shirt for the occasion. It read: “Goin' Richter.”

We went with Petr Kakes, a Czech national who placed sixth in speed skiing (that is, shooting straight down a steep slope) at the 1992 Winter Olympics. Kakes drove at least 75 the whole way, and we pulled some serious g's on the winding turns of Route 26.

I asked Johnson if he liked driving fast. “It's more of a thrill to shoot a gun,” he said. “I used to shoot birds that go in the ocean—any kind of birds that ate fish. I used to shoot them for themselves.”

We arrived at Creel's around noon, and right away he forked Johnson a cold beer.

“His mom said only one an hour,” Creel said, smirking.

“That's history now,” Kakes said.

We walked over to the Rainbow Tavern to get some sandwiches and ran into Gary Odam, a retired sheet-metal worker who'd met Johnson a couple of times the summer before. Odam insisted on buying Johnson a beer. “What this guy's been through,” he said, “I should buy him a jug of whiskey.” He turned to Johnson. “You were fucked up, man. But you came through. You got a lot of guts, man.”

“I do got a lot of guts, man,” Johnson said. It was impossible to tell whether the comment was a wry quip or just vacant mimicry. But it carried a glint of the old cocky Johnson, and Odam loved it.

“Let me buy you another one,” he said. “I can't think of anything that'd be more of an honor to me. What you did at the Olympics, it was phenomenal! Man, that was like those guys landing on the moon or something! All the bars and taverns in Portland were full, and everyone was ecstatic. I mean, people were going fucking crazy that night. Crazy!”

For a short while after he won the gold, Johnson was a national hero. He made the cover of Sports Illustrated. He got a Porsche 911 and an Audi Quattro, along with fat victory payouts from Atomic and his other gear sponsors. Corporations paid him to show up at their ski outings.

He did not, to put it mildly, husband his resources carefully. He bought a house overlooking California's Malibu Canyon; a pickup truck; a speedboat. He paid for most of it with cash. Herhusky remembers seeing him once with $40,000 worth of $100 bills in his pocket; the serial numbers on the bills were consecutive.

Johnson met and later married a waitress from Lake Tahoe named Gina Ricci, and the couple traveled in style. “I visited them once at a resort and they were in a high-rise suite, with flowers all over the room,” says Herhusky. “We were eating chocolate-covered strawberries and drinking champagne.”

Johnson lived like a rock star, and his skiing suffered for it. He showed up for the 1985Ð1986 season out of shape and he crashed hellaciously in Italy, wrenching his knee and herniating disks in his back. “He came to Tahoe to visit me in a cast, bent and broken,” recalls Herhusky, “and he just went crazy, gambling, partying. He went to the casino four days straight.”

His 15 minutes of fame were over. The endorsements stopped flowing, and in the late eighties he sold the Malibu house. He and Gina began wandering California and Oregon in an RV, with Johnson, a skilled carpenter, picking up money here and there doing renovation work. He eventually landed a job with Crested Butte Mountain Resort in 1990; as the mountain's “ski ambassador,” he was paid to schuss with visiting journalists and corporate bigwigs. But Johnson had a bad habit of bombing the hill and leaving civilians in the dust. In 1995 Crested Butte canceled his five-season contract a year early.

“Americans want Olympic athletes to be wholesome, to have integrity, pride, and sportsmanship,” says Ryan Schinman. “Bill was outlandish.”

As his old teammates built solid careers in the ski industry, the gold medalist found himself on the margins. “Americans want their Olympic athletes to be wholesome—to have integrity, pride, and sportsmanship,” says Ryan Schinman, president of a New York marketing firm called Platinum Rye Entertainment, which has represented Picabo Street and other star performers. “Bill was outlandish, and he had his mother as his agent. What did she know about corporate America?”

For a few years after leaving Crested Butte, Johnson eked out a living on the appearance fees he made at King of the Mountain, a downhill series for retired greats. He never worked a steady job but spent his days scheming—trading stocks on the phone and laying plans to launch a senior ski-racing tour. After he and Gina moved to San Diego in 1996, he played tons of golf. “He fell in with a bunch of guys who had nothing to do but play golf with a bottle of Jack Daniel's,” says Herhusky. “He'd stay out for days at a time.”

There was tension in the Johnson household, and also bad luck. In 1991, while Bill was caring for his one-year-old son, Ryan, the boy quietly let himself outside and into the hot tub. He didn't drown, but he came so close that, after he spent three hopeless weeks on life support, the Johnsons made the agonizing decision to let him die. They had two more boys—Nicholas in 1992 and Tyler in 1994—but the marriage ended for good in 2000.

Gina now lives with the kids in Northern California, where she works as an orthodontist's assistant. She did not return my phone calls. Bill sees her and his sons rarely, and since his crash he has lost all comprehension of why she vanished from his life. “The real tough part is my wife, the thing with me and my wife,” he says. “I don't understand why she doesn't want to be with me. I told her all I want is love. She doesn't understand I don't have a life. My whole life is lost.”

The Deschutes River tumbles down from the high lava fields of central Oregon, through ranches and pine forests and over myriad whitewater rapids on its way to the city of Bend. It's a fisherman's paradise, and in October the returning steelhead are profuse if you know where to look. Creel took us a few miles outside Maupin to his favorite fishing hole, and we unloaded the rods and the beer. Gary Odam, the guy from the bar, arrived with a 12-pack of Hamm's.

Johnson threw a hook into the water and Creel, who stands six-foot-two and weighs 200 pounds, lingered on the bank, exuding the mangy power of an athlete just a few brewskis past his prime. He popped open a fresh beer, took a drag on his Marlboro, and began to describe his training plan for the upcoming winter.

“This year, we're just going to get our feet under us,” he said. “It'll be about getting out there and skiing. We'll go poach a course now and then, and yeah, we're gonna play to win. It'll be extreme and it'll be flat-out because here's the deal: We can get back on the team. We just gotta pick the right courses. We don't want the turny ones. We want the ones where he can go 75, 80 miles an hour.”

I figured Creel was rhapsodizing like this for Johnson's benefit, but I looked around and saw that Bill was well out of earshot. I can only conclude that the beer was working its magic, because a few days later, in sober reflection, Creel would shun all talk of a Johnson comeback. “Trying to make the team was hard enough for Bill the first and second times,” he would say. “What person in their right mind would want to be involved with that scenario a third time?”

On the river, though, Creel envisioned great things. “We're going to the Olympics,” he said. “The drill is, we're trying to light the torch.”

Creel meant the Olympic torch. He and other Johnson friends had been lobbying the U.S. Olympic Committee since last May. There was, of course, a chance that their man would be chosen, but it was very slim. By the time of his accident America had largely forgotten Bill Johnson, and that hasn't changed, despite the made-for-TV drama of his recovery from a coma. Even in the ski world he's inspired only qualified sympathy. The U.S. Ski Team posts Johnson updates on its Web site, but has yet to sponsor any fund-raisers.

So Johnson was lucky to have someone like Creel. Here was a guy who truly believed in Johnson's greatness, even when doing so was absurd. Creel believed in the particulars—the torch, the fame that would have come after that dogleg turn at the nationals—and he did not regard this fishing trip as baby-sitting or an act of charity. He and Bill, he told me, were on a nonstop adventure.

We caught nothing all afternoon; we didn't even get a nibble. Everything was quiet and still until about four o'clock, when suddenly I heard something go splash. It was Johnson. He'd slipped and fallen into the river and now he was floating there, his head up and his eyes bulging.

Kakes got to him first. He anchored his powerful legs on the bank, pulled Johnson out of the water, and rushed him up to the picnic table.

“Take off your socks,” advised Creel.

“Here, use this towel,” said Kakes.

“Take off your shirt,” said Creel.

“Aw, hell,” said Odam, “why don't you just take it all off and give us a table dance?” Johnson threw his head back and laughed, and then we fished for a couple more hours.

DB picked us up near Kakes's house on Mount Hood that evening. She knew about Bill's fall in the river (he'd called her from Creel's), and she had the heat cranked up in the car for him. “We forgot to pack you an extra set of clothes,” said DB. “Next time we'll just send them along whether you like it or not. Are you warm enough?”

It was 79 degrees in the car, according to the gauge on the dash, but he wanted it warmer. DB turned the heat up a touch and then smiled over at Bill. She was just recovering from abdominal surgery and yet here she was, driving an hour to get us.

DB told me she was prepared to care for Bill until infirmity stopped her, and I thought of what his doctor, Molly Hoeflich, had said about the importance of this kind of care and attention: “If you go into any city in the country, you see people with cognitive deficits who live on the streets because they can't function in the world; they have no one to take care of them. These people just spiral downward. They get in fights. Their brain damage gets worse. Bill is doing well largely because he's gotten tremendous love and support.

“But is this enough? I hear people say, 'I got better because I really wanted it, because my family really wanted it.' But there are people who really want it and don't get it. Bill's outcome,” she concluded, “is becoming increasingly predictable. He will improve, but not drastically.”

We drove on. Johnson told me he could hit a golf ball 300 yards. He reminded me, again, that he'd won the gold medal. Eventually his mother mentioned that the next morning she'd be taking him to a health club for his first visit.

“You can lift weights, Bill,” she said.

“That's good,” he said, “because all I want to do now, all I want to do now—” We reached the Johnsons' driveway and DB turned in as Bill groped for the words. “All I want to do now is be a weight holder.”

“Oh, Bill,” said DB. She turned off the car and patted him on the back, gently.

Johnson smiled at the gesture. Then he followed his mother across the driveway and into the house.