WHEN PEOPLE HEAR ABOUT MY BACKCOUNTRY igloo project, they sometimes cock their heads and look at me funny. I admit, it sounds foolish—spending thousands and blowing off work to build happy fun pods. But after they hear the whole story, they just want in.

“Call it an igloo village,” I say to Nancy Pasternack, a friend and colleague. It’s November. We’re in a bar in Bend, Oregon, with snow piling up outside—the soppy kind that makes for excellent igloo mortar. “Envision not just one or two igloos but many,” I tell her. “I’m thinking of at least a dozen out there.”

“Out there” is the Deschutes National Forest, just east of the Cascades. Drive 20 minutes from Bend and you’ll find 1.6 million acres of old-growth forests, bulging volcanoes, and easy ski glades that groan under 20 feet of snow every winter. It’s the best mountain real estate money can’t buy: spectacular views, quiet lakes, unlimited natural runs. An igloo development will be my own destination resort, a place where my friends and I can warm up with hot chocolate and slippers before venturing back out for more turns. Tents would never last, and snow caves are too confining. But igloos, built in the shade, should hold up most of the winter.

“Poor man’s ski cabins,” I say. “Lay down indoor-outdoor carpeting. Stash some fuel. We’d never need a ski pass again.”

Nancy looks confused. Like many people, she’s probably never seen a real igloo. So I cup my hands, palms down, to approximate an igloo shape, and then move them all over the place to suggest many. This might also suggest “maniac.”

A few months ago I’d never seen an igloo, either, and I assumed they were a hassle to build. But after Googling “winter camping shelter” one night, I stumbled upon the Icebox, an igloo-building tool that promised fast-‘n’-easy ‘gloos strong enough to stand on. So I ordered one, imagining tuckered skiers and weary snowshoers filing over a ridge to discover—what’s this?—an igloo village!

“That’s a great idea!” said my friend Tania Kneuer, an occupational therapist. “It’ll be like building forts.” She and her husband, Scott Weber, signed up, as did my office mate Alex Berger.

Of all the people I told about the village, few ever asked why I wanted to do this. Nancy didn’t. Alex didn’t. My fiancée, Heidi, did—but only after I’d dropped $2,300 of our money on a snowmobile. How else was I supposed to ferry in sleeping bags, tiki torches, and other amenities? I named the machine Betty.

“Why do you want to do this again?” Heidi asked when I fired Betty up in the garage, anxiously awaiting the first snow.

“What do you mean why?” Betty and I rocketed out into the driveway, her track spewing gravel all across the yard.

SNOW SEASON STARTS slowly, but by Thanksgiving a veritable winterkrieg has strafed the forests with fine white pellets. We load up and head out.

Betty purrs comforting clouds of blue smoke as we motor north of Mount Bachelor, cruising past fellow snowmobilers, who raise their fists in salute. We must look like a hippie junk show. Tania and I sit squished on a one-person seat. Scott rides backwards on a trailer so he can hold on to his dog, who’s freaked out. Alex tows behind us on his telemark boards, clutching a rope like a water-skier. “Woo-hoo!” he shouts, scribing a few S’s in the snow.

As with all real estate, location is the most important factor when building igloo villages. “How about Todd Lake?” Alex suggests when we stop to rearrange the gear. “It’s a perfect spot.”

With its Forest of Endor landscape, pleasant saddle, and tumbling ridges, Todd Lake is indeed a perfect spot. It’s about three miles from the trailhead, so people can reach it on skis. “I guess we don’t need to worry about zoning laws,” Scott jokes. He’s right. Building igloos on public land—even a village of them—raises no more legal issues than building an army of snowmen. Being good developers, we’ll leave no trace. We stash the snowmobile near the lake, click into skis and strap on snowshoes, and slip past trees that are four feet thick.

“This is the place,” I say upon reaching a clearing high over the lake. I haul out the Icebox. “Igloo Ed says we need to build the foundation first.”

Ah, Igloo Ed, inventor. The man who makes it possible. Here we must pause.

The master and I have never actually met, but I know several things about Ed Huesers. At 58, he looks like half of a ZZ Top cover band. And, based on a photo he e-mailed me, he doesn’t wear pants, at least not when he’s wading across streams in winter. “It was ten degrees out that day,” he wrote, looking like a hero.

“For me, igloos are just superior,” Ed says, noting that even modest-size igloos are twice as roomy as a three-man tent. They’re also quieter and warmer, because the thick blocks of snow hold in body heat.

But the problem with making traditional igloos—by stacking blocks in a dome shape that you hope will hold—is that they collapse easily. “It takes a lot of skill to get the right curve,” says Ed.

The right curve is the catenary curve—a self-supporting structure like the Gateway Arch, in St. Louis. Ed, a machinist from Longmont, Colorado, set out 13 years ago to design a kit that would help you build consistent blocks and set them into a stable dome. In 1998, he emerged from his garage clutching what became U.S. patent number 6,210,142 B1: the Icebox, which is a plastic block-shaping form attached to a telescopic pole. The form makes perfect blocks, while settings on the pole guide their placement. At $170 a pop, the kit makes bombproof domes that spiral up like a spring.

Ed makes ‘gloocraft look easy, but at the site we’re having problems getting the blocks to line up properly. It takes us six hours to do what he does in three, but the walls rise steadily. By dusk, we’re looking at two completed igloos.

“This is so cool!” Tania says as we belly-slide like penguins into the enclosure.

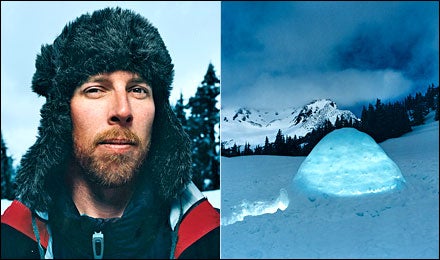

Soft light filters through the walls. We high-five and kick back as the temperature inside begins to rise. We dub the first structure Gloo Eins, because that sounds better than Gloo One. We call the second one Bigloo, because it’s big and sexy.

“This igloo village shall forever be known until spring as Glooville,” I proclaim. “Now let’s get out of here.” It’s Sunday, so we can’t stay, and a storm’s rolling in. Betty gets us out in time.

I HAVE TROUBLE getting back to the site over the next few weeks, what with the holidays and all. In December my parents fly out but decline my offer for a “really white Christmas.”

Alex, however, tells me he’s skied to the site a couple of times to spend the night. “Looks like they’re holding strong,” he reports. “Bigloo has compressed a bit, but it’s basically the same shape.”

New Year’s is ours, and Heidi and I plan a trip to the retreat. Our friends Bethany Graham and Christopher Laws join us. We head out at 9 a.m., breaking trail up 600 vertical feet and around a steep cliff to reach the site by noon. Gloo Eins and Bigloo now have at least four more feet of snow on top, but their pillowy backs are still easy to spot. Christopher and I dig out the doorways. Glooville is buried so deep that it feels like an ant farm.

“Let’s build one here,” Christopher suggests, pointing to a spot between some evergreen trees. In just three hours our friends are looking at their dream igloo, a nine-foot-diameter beehive. We name it Gemütlich Gloo. It stands on the edge of a lake, its walls smooth as ice cream.

“What do you say? Dinner, our place, at seven?” Bethany says. Sounds great.

With darkness coming, Heidi and I return to Gloo Eins and fluff our sleeping bags. We rest a few hours before going back out. The temperature has fallen into the teens; moonlight wafts through the trees. The dome of Gemütlich Gloo oozes an ethereal glow, like some sort of dragon egg.

“Happy New Year!” Bethany shouts when we slither in. “Take a seat!” Her boots are off, and she’s snuggled up in fleece and thick socks. Christopher cooks soup and pasta in a makeshift kitchen.

It’s only 8 p.m., but things already look festive. There’s whiskey and Trivial Pursuit, but by ten Heidi and I are sound asleep, warm and cozy even as the temperature outside plummets. Tomorrow we ski. It’s the best New Year’s ever.

IN THE GLOOVILLE of my dreams, the village takes on a life of its own, with friends building ‘gloos and ice sculptures all along the lake. Come April, just before the whole thing melts, our igloo society could throw a party—a snow festival that gives thanks for a wonderful winter. Problem is, no one really knows about any of it.

“Go viral,” says my colleague Harold Olaf Cecil, owner of a Bend marketing firm. “We can create a Web site, make some stickers, create a logo.”

Things start well. An artist friend in Maryland designs a logo with the silhouette of an igloo among mountains. I talk about the igloos in lift lines, dropping clues like “They’re near Mount Bachelor” and “It’s easy to ski in.”

But as January slips into February, I get distracted by work and the viral campaign fizzles. Tania is pregnant. Alex gets a new job and doesn’t visit for a while. “I went out this weekend, and you can just see a slight depression where the doors might be,” he tells me. “They’re still there, but digging down will be a bitch.”

By March, Glooville wheezes under at least 12 feet of Oregon snow. “Oh, well,” says Alex. “There’s always next year.”

I AM UNDETERRED. As spring pushes the sun higher, I rally. This time I’ll build a whole new village, a dozen at once, in a sweeping meadow deeper in the wilderness. I order two more Iceboxes, top off Betty’s tank, and sound the battle cry.

“Friends, countrymen, fellow lovers of spring: Wait! Winter hasn’t gone away completely yet, and that means igloo party,” I write in a mass e-mail. “With three people working per kit, we can crank out three to six igloos each day. Who’s in?”

The transmission is a bit unnecessary, since my gimp viral campaign has somehow worked. In fact, it’s kind of shocking. Women have stopped me outside the pub to ask me about my igloos, a first on many levels. E-mails fly in.

Brett: “My ‘gloo’s gonna rock! iPod speakers?”

Jill: “FUN! I’m 75 percent so there!”

Then this: “Hello! Your e-mail was forwarded to me through a few friends. I wanted to let you know that both my hubby and I are in for Saturday.”

I have no idea who she is, but I type back, “That’s great!”

It takes two days for Betty and me to ferry in what feels like 500 pounds of bacon, burger, cheese, eggs, candles, pots, pans, skis, chairs, and a two-burner stove.

“I’m excited!” reads the last e-mail I get from Tania, now almost four months pregnant, before I head back out.

But Tania doesn’t make it, nor do most of the others. The weather drops from 45 and sunny to 25 and soup. It snows so hard the morning of the big day that our junkyard caravan gets lost in a whiteout. “We’re getting hosed,” Heidi relays into her cell phone to friends debating whether they should come.

With half the day gone, the seven of us who do make it manage to build just two igloos and part of a third. One friend’s face swells up so much from windburn that you’d think someone had stuck a pump in her. I sleep terribly that night, getting dripped on the whole time.

“I think I’m ready for winter to be done,” Heidi says the next morning.

Maybe I am, too. But then I poke my head out and see that the storm has passed. Broken Top, a 9,175-foot volcano, glows pink in the pale morning light, snow spackling its summit. Everywhere I look, buttery lines slip through trees and bowls now choked with a foot of fresh.

“That’s beautiful,” Alex says, stretching outside his igloo. “Want some bacon?” Others emerge. We all look worked—but relieved and somehow satisfied, too.

By now the ski lifts at Mount Bachelor are warming up. No doubt the slopes will be chewed by noon. Here we laze in the warming sun and drink coffee. There isn’t a soul around. In the distance I spot a lovely ridgeline just beggin’ for a ‘gloo.