Beth Rodden on Her Kidnapping, Motherhood, and Climbing

After bursting onto the scene as a teenage gym rat, Beth Rodden became one of the most accomplished climbers of all time. Here, for the first time, she opens up about the price of perfectionism, the kidnapping that almost grounded her, finding love again after her marriage to big-wall prodigy Tommy Caldwell, and balancing motherhood and rock.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Before I was kidnapped, before I discovered the chaos that is true love, I believed in routine. Even in high school, mine was Âornate. Monday, climb at gym. Tuesday, rest. Wednesday, train lightly, eat Bisquick biscuits and eggs for dinner. On Thursdays I packed. I stored my gear for climbing competitions in individual Ziploc bags—my purple climbing shoes in one, my blue Verve chalk bag in another, my black in a third. Then I placed the bags in separate pockets of my purple backpack.Ěý

The XX Factor Issue

Our special issue highlights the athletes, activists, and icons who have shaped the outside world.

Our special issue highlights the athletes, activists, and icons who have shaped the outside world. Friday morning I prepared my road food: Just Right cereal, with the raisins picked out, in a Tupperware container, plus four apples, cut into slices, some of which I’d eat on the plane. That afternoon my father and I flew. Once on the ground, we rented a car from Hertz—always Hertz. We requested a Mercury Mystique every time. “Mr. Rodden, you have an interesting rental history,” a desk clerk once said. My dad just smiled. We stayed at Courtyard by Marriott, even if it meant an hourlong drive to the climbing gym, and ate dinner at Olive Garden. Each night before a national indoor climbing competition, I consumed two and a half breadsticks, one order of penne with red sauce, a side salad, and a virgin strawberry daiquiri. In the morning, I showered and drank a bottle of Evian. Then I put on my faded light green sports bra, my black shorts, my thick green socks, my , and my father’s patterned fleece. I was 15 years old, five feet tall and 80 pounds, and I could do . If I placed first, second, or third, I rewarded myself with a double scoop from Baskin-Robbins—always Gold Medal Ribbon and mint chocolate chip. Always in a cup, no cone.Ěý

My parents were my biggest supporters, encouraging but never pushing. My routine, my regimen, was self-imposed. I was superstitious. I liked my life at home in flat Davis, California, efficient and hyperrational. I thought parties were a waste of time. I stressed so much over schoolwork that I gave myself blisters taking endless notes, while my brother aced everything without studying.Ěý

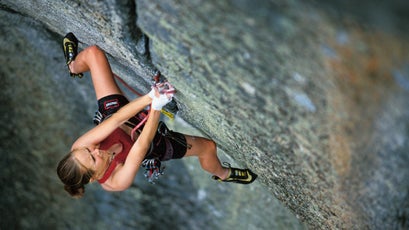

After high school, I enrolled at the University of California at ÂDavis and continued living at home. Dorms were out of my comfort zone. My college classmates stared at me as if I were a genius ten-year-old. Finally, in the summer of 1998, when I was 18, I started to sprout—a bit. I got all the way up to five-one, 85 pounds, at which point my body started feeling heavier when I pulled on plastic holds. I didn’t love that, so I figured it was a good time to pursue more outdoor climbing, which rewarded . The truth is, I’d never really spent much time on the actual rocks pictured in the posters on my bedroom walls. So, in what was then my most Âdaring move to date, I took the second semester of my freshman year off and drove my Honda Civic up to Oregon to live at , one of the best places to prove yourself in American sport climbing. My goal was to complete a route called . At the time, it was not only out of my range—it was out of the range of every other young woman climber. My hero, , had become the first woman to climb it just the year before.

Beth Rodden Podcast

The star climber opens up about her kidnapping and finding love after a broken marriage

The star climber opens up about her kidnapping and finding love after a broken marriageI loved seeing how my body adapted to a long, difficult project, even how my skin tore and healed. But I fell—a lot. Weeks went by, then months. I kept picking away at the moves, diagramming them on paper; here you grab a hold the size of your finger pad, there you slowly transfer your weight to a dime-thin edge. But I couldn’t string them all together.Ěý

Then Lynn Hill herself showed up. She was terrifying: no bigger than me but ten times stronger and a thousand times more self-Âconfident. She had huge biceps and beautiful bronze skin. She lived nearby, in Bend, and when she got back to Smith that May, she Âcasually became the first woman to climb a . Probably because she was there, I finally collected my own machismo, such as it was, and refused to fall on To Bolt or Not to Be. That night Lynn threw a pizza party for me to celebrate. I was really living on the edge, eating sausage instead of pepperoni, and she asked if I wanted to join her on a climbing trip to Madagascar. I tried to keep a straight face when I eked out a yes.

To say that I was unprepared is too generous. I had zero experience with real adventure, none on rock walls over 200 feet. I didn’t know (ascend a rope) or properly place big-wall gear (camming devices you lodge into cracks). I was a kid in a high school musical invited to sing at the . A couple of months later, at the Atlanta airport, as I waited for my first connecting flight to Madagascar, my parents called the gate. I wanted to be above this, too independent and tough for such coddling, but my mother’s voice melted me with relief. I wanted her to be sitting beside me.

This was before I was taken hostage. Before I quit school entirely and married the man I thought I had to marry, built a dream house with him, and then flooded it.

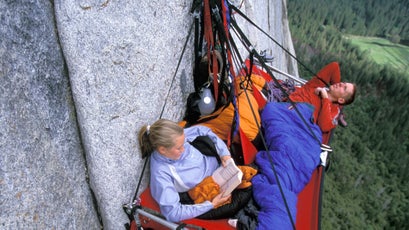

blew me away—2,500-foot overhanging faces, smooth as bedsheets, with tufts of grass sticking out like buttons. On our way south from Antananarivo, the capital, armed guards stopped our car and demanded that we take cholera pills, as there’d been an outbreak in the northern part of the country. Our guide told us just to hide them under our tongues—a Âwoman ahead of us had taken one and started throwing up beside the road—but I was immediately sorry I’d come. I cried during the whole approach to the base of our route, which we’d name Bravo les Filles. I exhausted myself utterly that first week—not by climbing but from coiling ropes, finding the soup at the bottom of the haul bag, repacking the haul bag, realizing I’d forgotten to pull out the can opener, and unpacking the haul bag again. Even peeing nearly broke me, as it required making sure that the rope was not below me, people were not below me, and the wind was not going to fling my own urine back in my face. My fingers were so raw and swollen, I couldn’t work the Fastex buckle on my harness.

The next week I had more resolve. My body started adjusting to the devastating labor of a big-wall siege. I developed my own set of smaller but still remarkable biceps. My mind started adapting to the never-ending challenge of domesticating fear, narrowing my Âfocus to the task at hand. I was not quite an adult but also not a child anymore. I’d grown to love the radical self-reliance. The feeling of exposure. After several weeks in Madagascar, I flew home, stopping in Austin, Texas, for a climbing competition. The gym felt dirty, chalky, and small.

But this, too, was before I was taken hostage. Before I quit school entirely and lived in my car, eating canned food and trying to become a professional climber. Before I married the man I thought I had to marry, built a dream house with him, and then flooded it. Before I blew that marriage up.

A year later, in June 2000, Tommy Caldwell, Jason Smith, John Dickey, and I landed in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, and helicoptered into the Kara Su Valley. The valley is located in the Pamir-Alai range, in the country’s southwestern tip​​, a finger poking in Âbetween Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. ​​We were there on a six-week trip Âfunded by my then sponsor, the North Face. , and the were dramatic looking and rarely photographed, thus great for ad campaigns and first ascents. ​The four of us were unaware, however, that the area sheltered Taliban- and Al Qaeda–inspired militant groups like the (IMU).

I was so happy to unpack our expedition duffels and nest. I organized my clothes into perfect piles. I took PolaÂroids of ÂTommy and me and taped one of them above my sleeping bag in our tent.Ěý

Tommy and I had taken an unusual path. We’d known each other for years, from climbing comps, but our first date had been just that April in Boulder, Colorado. He picked me up in his gigantic Chevy van and took me for an Âearly-bird Caesar salad at a Cheesecake Factory. For our next date, more or less, we spent a month sleeping in the sand at the base of El Capitan, in Yosemite Valley, working on a . Tommy—a well-mannered mountain boy, son of a former Mr. ÂColorado bodybuilding champion, and all-around climbing superstar, with freckles and a long, straight nose—was my first boyfriend. He was perfect. He’d just established the hardest sport route in the country at that time, a , in western Colorado. He moved his body over the rock with tactical grace. He carried far more of our gear. He coiled our ropes, he gave me privacy when nature called on the wall (), and we didn’t have sex. We were both inexperienced and immature, sure, but mostly it just didn’t feel urgent. We’d lie in our separate sleeping bags, fixed lines dangling like balloon strings from the sky, talking about future climbing trips and the curtains we’d sew for his van.Ěý

But at the same time, I was realizing that, for me at least, the romantic part wasn’t really there. A week before we left, at the North Face’s corporate headquarters, I tried to break up with Tommy. I told him I thought we should just stick to being friends and climbing partners. He laid his dirty-blond head on the floor. Neither of us was particularly strong and brave about emotions. He asked if we could please just go on the trip and see how we did. I hated conflict. I said yes. I was 20 years old, and Tommy was 21.Ěý

When I look back now at the pictures of us at that time, I see Âchildren.Ěý

For our first project in Kyrgyzstan, Tommy and I started working on a route up the Yellow Wall, a 2,500-foot line on a granite face covered with lime green lichen. It took us days of feeling around for foot- and handholds we could use to tic-tac our bodies up the slab. Jason and John joined us on what we figured would be a three- or four-day push; we loaded gear, food, and clothes into haul bags, clipped on portaledges to sleep, zipped the rest of our supplies into our base-camp tents, and started up. Our first night on the wall was August 11, Tommy’s 22nd birthday. I brought along a candle and some freeze-dried chocolate pudding and sang “Happy Birthday.”

We woke to gunfire, three men taking haphazard shots up at us, and I immediately started crying. More than fear, I remember, I felt regret: Why had I ever left Davis? John, at 25 the eldest among us, volunteered to rappel down to talk to the shooters. He brought along a two-way radio. On the ground he offered the men cigaretÂtes. They scoffed at the gift.Ěý

John radioed up to us: You need to come down.Ěý

Numb looked stoic, and I didn’t want the boys to know how scared I was. That was the climber mindset: don’t show weakness. Deep inside, my mind looped on the worst.

The men had black hair, beards, grenades, rifles, and knives on their belts. Two appeared to be our age, the other a decade older. They were IMU fighters.

On the forced march back to our base camp, I tried to hold on to the assumption—the hope—that they just wanted our money and gear. But the camp looked like a crime scene. The militants had sliced open our tents, and our gear was strewn everywhere. We noticed another man, who sat slumped against a rock. He had blood on his pants and a flannel sleeping bag under his arm. His name was Turat, and he was a young Kyrgyz soldier. He ran three fingers across his throat. Eventually, we got his message: He’d been captured with three other men. The others had been killed.Ěý

Our captors barked and gestured for us to get our passports. We grabbed our warm jackets and stuffed the pockets with PowerBars. John found a Polaroid I’d taken of Tommy and me and showed it to our captors, on the theory that if they thought I was married perhaps they wouldn’t rape me. I started to go numb, which was maybe good? Numb looked stoic, and I didn’t want the boys to know how scared I was. That was the . Deep inside, my mind looped on the worst. If I was going to be raped, I wished I wasn’t a virgin. I wished I’d had sex with Tommy first.

We marched again, this time with Turat, our fellow hostage, but later that day, just yards away from us, during a firefight with the Kyrgyz army, they took Turat behind a rock and shot him in the head. I couldn’t let Âmyself process that, because it would have ruined me, and some part of me understood that if I was ruined, our captors would think I wasn’t worth saving.Ěý

That night the four of us huddled Âtogether under Turat’s sleeping bag and tried to sleep. At least we had each other. But in the morning, our captors split us into two groups: ÂJason and Tommy, John and me. We’d be easier to hide that way. The older captor, called ÂAbdul, pointed for John and me to squeeze our bodies under a boulder right next to a wild river, our cheeks inches from the ground. The Âwater level rose through the day as the sun melted the glacial snow. Our clothes got soaked, and my jaw ached from clenching my teeth. Abdul gave us no food—he had none. He had no warm clothes, Âeither. At night, while we marched, each of us ate one PowerBar, our calories for the day. We shared the food with our captors. We needed their mercy. The next morning, the same routine: hide, starve, freeze. I spooned with John to keep warm. He asked me with such kindness to describe my favorite meals, my childhood home.Ěý

I smiled at Abdul with the hope that he’d like me and therefore save us. He masturbated a body length away. Then he got cold, or lonely, or bored, and crawled under the boulder to spoon with us. I remember his facial hair. I remember his smell. I was so repelÂled by him holding me, but I needed the warmth. I tried to find my climber’s mind, my ability to focus on the small space directly in front of me, to tame fear. I was relieved I was not with Tommy. I knew his parents. I knew his childhood bedroom. I felt responsible for him. At night, when the whole group came back together to walk, Jason and John discussed how we could kill our captors. There were only two now—Abdul and a clumsy young man we knew as Su. They were ill prepared for navigating mountain terrain. On the fourth night I collapsed, literally—I fell over while we walked down a hill—but I also just gave up inside. I could not stop shivering. I could not stop crying. To our horror we realized, looking up at the cliffs, that the men were walking us in a circle. Not even they had a plan for this to end.Ěý

On the sixth day, Abdul took off to find food, warmer clothes, and batteries for their radio. That left all four of us with Su, who stumbled like a fawn on critical terrain. We started up a slope that grew sharply angled and then cliffed out near the top.Ěý

“Do you think I should push him?” Tommy asked me. The boys had talked of nothing else all day. I didn’t say no. I didn’t say anything. This was clearly our chance. It took only seconds for Tommy to climb above Su. As Su started up the headwall, Tommy yanked Su’s gun strap, sending him tumbling off the cliff. Su’s body made a crunching and then a deflating sound when he bounced off a ledge.

Tommy broke down moments later. He worried that I could Ânever love him after . In my own traumatized state I reassured him that yes, of course I could still love him, but inside I was also telling myself that I could never leave ÂTommy now.Ěý

We ran about eight miles that night, weirdly singing as we moved in and out of the moonlight. We hoped to find an army compound that we’d noticed during our first week. When we got close, Kyrgyz soldiers fired warning shots, but we shouted “Americans! Americans!” and they stopped. Inside they gave us water, tinned sardines, and cigarettes. The next day, we were taken to another army base and ultimately made it back to Bishkek, to the U.S. embassy. Nobody back home had even known we’d been kidnapped.

Back in Davis, life felt swirling and chaotic. Inside, on my own, I was numb. My mother, in shock herself, treated me with utmost tenderness. Neighbors and girls I hadn’t really been friends with called and dropped by with what I’m sure were good intentions, though their interest felt prying and made me retreat. Meanwhile, the . “Whoa, what an epic!” Some climbers even seemed envious of the attention, like we’d overstepped our station by having this horrible sufferfest that was suddenly all over the news.

Tommy stayed in Davis for a while. I crawled into the double bed that my parents installed in my bedroom for the two of us. I’d long struggled with food, restricting calories, and now I ate and ate and ate. But soon, Tommy’s father mentioned that we hadn’t climbed in a few weeks. That’s what was on his mind? Tommy, too, true to how he’d been raised, wanted to use our horrible experience to grow. He wanted the . The hostage-crisis-as-epic narrative worked for him. We’d learned, during those six days, that we could endure even more than we thought possible, more than we ever had on our hardest climbs. Tommy had a clear vision of where his (our) life was headed. He’d pour himself into climbing. We’d be a team, stronger together. I had no vision of life at all, not anymore. So I went with his.

In May, Tommy helped me move out of my parents’ house, and the two of us settled in a 600-square-foot cabin near his parents in Estes Park. By then we’d learned that Su, miraculously, had survived his fall, and I had put myself back together, sort of, though what I’d really done was push Kyrgyzstan deep inside me and winched it down in a compression sack. I wanted to return to being perfect. I tried to make my relationship—the one that I wasn’t even sure I wanted to be in—perfect, too. I asked a jeweler to create a silver pendant for Tommy. An inscription read T.C. MY HERO. MY LIFESAVER. MY LOVE., and he wore it on a leather cord around his neck. I asked him to carry me across the threshold when we arrived at the cabin, because that’s what perfect couples did. This was my first home outside my parents’. We gutted it and rebuilt it ourselves.

I wanted to love climbing again, too, though being cold or hungry now sent me into shock, so mostly we just trained. Years Âearlier, ÂTommy’s father—a gifted climber himself—had turned the family garage into a home gym. During his bodybuilding prime, he’d Âwelded his own barbells and dumbbells and made his own lifting benches. Tommy’s mother crafted cushions for them. When Tommy became serious about climbing, his father added a freestanding garage, complete with an apparatus we dubbed the Finger Machine, a handful of metal scraps welded Âtogether for the purpose of turning Tommy’s digits into steel. His parents were avid do-it-yourselfers; they believed we were capable of anything.Ěý

I was unnerved by all the emotions that poured out of me.ĚýHappiness, satisfaction, but mostly relief. This had been a dream for so long. Now that I’d attained it, I thought I would feel calm inside. I thought I would feel happy and strong.

The gym also had a 12-by-12-foot climbing wall, cantilevered out to 43 degrees, with some mattresses on the floor to protect from falls. There was no insulation. No paint. Not even colored tape marking boulder problems. I gladly worked myself to exhaustion in there, partly because I loved training but for two other reasons, as well: one, I wanted to ; and two, I needed to defend against the inevitable criticisms that would arrive each month with the climbing magazines. If neither Tommy nor I was prominently featured, Tommy’s father expressed his concerns. He chafed when somebody like put up a new ascent. “What’s this route that Dave did? Is it harder than Kryptonite?” he’d ask. “What’s he doing that you’re not? You really need to be focusing on training and not slacking off at the gym.” It didn’t seem to faze Tommy; he’d just nod, smile, and say, “Yeah.” Then he’d train harder.

In November 2001, a month after my first hard route since the kidnapping, I was talking on the phone with my mother when I heard Tommy scream—the same scream I’d heard after he pushed Su. I dropped the phone and ran to the storage room at the back of the cabin where Tommy and I had been building a platform for a washer and dryer. The table saw was still on. His left hand and forearm were covered in blood. he yelled, running around in a circle. “I cut off my fucking finger!”

I tried to shout over him that everything was going to be OK, though obviously it was not. I found his left index finger in a pile of sawdust. It was still rough and thick with calluses and warm to the touch, and it felt like his fingers always did when I held his hand. I put it in a Ziploc bag with water and ice. Tommy wrapped his hand in a towel. As I sped through town, I ruffled Tommy’s hair to try to keep him calm, and by the time we reached the Estes Park hospital, he had stopped screaming. We were good at this; he was good at this: calm under pressure. Doctors transferred Tommy to the larger Fort Collins hospital, where he spent two weeks. Surgeons reattached the finger, but blood kept pooling in it. So after another operation, they took it off.Ěý

By then we had a slide show we presented at climbing events. EveryÂone wanted to know about Kyrgyzstan, so we practiced a positive message: we got kidnapped, it was terrifying, we escaped, and we’re now better, tougher climbers for it. to his hand. Even before his stitches came out, he started climbing again. Six weeks later, he was doing boulder problems. Six months after the accident, .Ěý

Tommy was invincible, and I tried to be invinÂcible with him. We got married the following spring, in 2003. We had the same sponsors, the same phone number, the same e-mail address. We bought a vacant lot in Yosemite West, a private community Âinside Yosemite National Park, to build a house together. The plan—ÂTommy’s plan, our plan—was to pour all our time, energy, passion, and ambition into climbing.

It was working out pretty well. My dreams of pushing myself as a full-time pro, setting big goals and meeting them, had reawakened, and I was making a name for myself climbing short, hard cracks. Tommy quickly became the best at doing the first free ascents of old aid routes on El Cap. We traded off supporting each other on projects, sticking to one person’s for weeks, months, whatever it took. At Smith Rock, I made the first ascent of a route I called the , to that point the hardest first ascent by a woman. Together, Tommy and I free-climbed the Nose on El Cap in 2005, becoming the third and fourth people to do it. (The first, of course, had been Lynn Hill.) I sat on the top and took off my climbing shoes, staring at my swollen feet and Middle Cathedral as I belayed Tommy on the last pitch. I was unnerved by all the emotions that poured out of me. Happiness, satisfaction, but mostly relief. This had been a dream for so long. Now that I’d attained it, I thought I would feel calm inside. I thought I would feel happy and strong.Ěý

That elation lasted a few weeks, maybe a month. Then I didn’t feel strong anymore, not entirely. We continued climbing and climbing well, but Tommy and I didn’t talk about the past; we convinced ourselves we were moving forward. In 2006, we broke ground on our lot in Yosemite West, and that, too, felt great for a time. But soon I began to feel trapped building a house I no longer wanted to build, to shelter a marriage that had no levity or passion. We didn’t know how to relax together. We never took a vacation or bought a Christmas tree. The lovers part rarely happened and never clicked. Meanwhile, I was terrified to climb with any partner besides Tommy. I didn’t want anyone to even see me climb—I couldn’t deal with the extreme expectations I imagined the world had of me, to be a person who could climb 5.14 all day, every day; to be a person who looked like I did in the climbing magazines, a person who was endlessly patient, smiled nonstop, and wore perfect clothes. I . I resented Tommy for not saving me from the nights I binge-ate to fill an emptiness inside and then couldn’t sleep. I lived for the days when Tommy and I just disappeared, when we took road trips, slept in the van at a trailhead, and woke to our teapot frozen solid. We’d layer up under our expedition parkas and hike out to a remote crag. I’d climb in my long underwear and not feel ashamed.

In September 2007, I started working on an unnamed single-pitch route in Yosemite. , one of my teenage climbing idols, had put in the anchor bolts years earlier but never completed the route. The pitch was harder than anything that had been climbed in Yosemite before—I figured it was 5.14c. It was perfect for me: a long, thin fracture on a gently overhanging cliff that required intricate finger locks and Âoffered only the faintest footholds. For six months, as the weather grew colder, I worked the route, which I named , on a top rope. I warmed my fingers against the back of my neck, then let them freeze again as I twisted my fingertips into the rock. By January, I’d ignored two finger injuries and started lead climbing, duct-taping the gear to my harness so I could place it in the crack more quickly. I needed this, I wanted this—and as much as I rooted for Tommy to succeed, I was exhausted and didn’t want to resume jugging up and down El Cap as his support mule. Yet I wondered what was taking me so long. By early February, snowmelt was filling and spraying onto the wall. Then, on Valentine’s Day 2008, I sent the route. I couldn’t believe it when I clipped the anchors. , and I knew I no longer had an excuse not to examine the rest of my life.Ěý

That was the end of that. Tommy and I started to break down. We’d been perfect. There was nothing else to be perfected, and now I was miserable and constantly hurt. I tore a ligament in my finger. My body couldn’t take the cumulative stress. Meanwhile, Tommy kept soldiering on, his goals getting bigger, harder, Âfaster. I wanted to support him—I loved him, and that’s what we did. I knew, up on the wall, when he needed food, when he needed rest, when he needed to punch it into gear. But I was tired, tired of chasing achievement that I now knew for certain would never make me Âhappy. I became obsessed with normal. I knew nothing about it.ĚýWhen friends who I thought led blissfully normal lives Âchatted about hot sex—hotel sex, makeup sex—I just nodded, because I had no experience with the kind of passion they were talking about.Ěý

And then I met somebody.Ěý

I tried to forget about him, but I’d been trying so hard to forget so many feelings that I just couldn’t do it anymore. I knew that indulging these new feelings was awful and hypocritical. I remember once, years before, saying to Tommy, “I don’t Âunderstand. I mean, if you like someone else, get out of your relationship and then get into the new one.” But I hadn’t accounted for real desire. Now it overtook me like a wave. I had no practice with it, no defense. Not that I tried. I was ecstatic to be in love. I tried to summon the courage to make decisions with my heart.

Yosemite West is a horrible place for two people trying to figure out if they can stay together. It is so pretty, so quiet, so empty, surrounded by mountains so majestic that even on your best day you feel insignificant and small. I told Tommy about my affair on a warm October afternoon in 2008 while sitting in our living room, in a house we had built together, on a green couch given to me by my grandmother, who’d been married 50 years. He remained calm. He was a black belt at . Only once we Âstarted going to couples counseling did I see him explode. Later that fall, driving north on Interstate 5 toward our therapist’s office in ÂDavis, Tommy hit the roof of our Civic with his fist. The shade fell into his line of sight, and we swerved off the road.Ěý

“What the hell are you doing?” I screamed. “Who are you?”Â

We both cried. He said, “I’m so sorry. Please forget this.”

So we reverted to stoicism. Both of us just kept climbing. Of course we did. Randy, the man I’d fallen in love with, was a software engineer in the Bay Area and an expert boulderer, but climbing was his hobby, not his job, and he didn’t understand the rigid pro-athlete part of me. Randy liked staying up late. He liked eating pad thai. Some days, when he’d planned to go to the gym after work, he changed his mind and met friends for beers instead—the gall! Tommy moved out. It was awful. I could see him grow hard, use his on the problem of the suffering caused by me.Ěý

On my own, I started working on a route called . I thought that if I could just finish Magic Line, I’d prove to myself that my athletic prowess would not disintegrate if we split up. One cold November morning, I thought I had it. My hands and feet were freezing, but I was a few feet from the top. Then, just as I was starting to enjoy my success, my imagined liberation, I felt myself go airborne.

I drove home, rested, kept training through late fall. Randy was patient, supportive, and thrilling to me, but he also had limits. The first time I tried to serve him French toast in bed at 5 a.m., so we could still reach the crag by dawn, he groaned, rolled over, and went back to sleep. Didn’t he realize that the route went into the sun at 11 a.m.? That I was my best in the morning? He still lived full-time in the Bay Area, and wisely he suggested that it might be good for me to get some distance, to stop beating myself up trying to do Magic Line in winter and instead leave Yosemite and this house for a while. Before I departed I turned off the main water valve—I thought. But the water to our subdivision had been turned off that morning, and I’d opened the valve instead. For six weeks it ran, flooding the house.Ěý

Tommy and I divorced in 2009. I bought him out of the ÂYosemite house; he kept the cabin in Colorado. In 2012, Randy and I got married. This time it felt different. I loved him, yet we remained two distinct, flawed people: . In 2014, we had a baby boy, Theo. Babies, for everybody, require letting go and facing who you are, and I had an especially big job ahead of me given how thoroughly I’d bound up my emotional life with achievement and control. We split our time between Yosemite and the Bay Area, and one day, when I was with Theo in a park in Berkeley, he started playing with a child who looked Middle Eastern—a beautiful little kid, a toddler—and my first impulse was to pick up Theo and leave. I’d been scared for years, ashamed that I switched grocery lines when men with the same complexion as my captors came up behind me, but not ashamed enough to dig into all the trauma I’d shoved in a box. Now I was trying to live a real life, with real love and relationships, and I didn’t want to pass my baggage on to my son. Theo waved to everybody. He dawdled. I loved his wide-open face. So I called a therapist and started to talk about Kyrgyzstan, the experience that had sent me rushing back into my perfectionist ways just when I should have been leaving all that behind. I tried, as best I could, to set aside my climber persona, that grandmaster compartmentalizer of fear. I wanted to be a good mother. That meant facing my life as a vulÂnerable, imperfect mess.Ěý

This process was, as the boys might say, epic in its own way. The details remained so vivid, especially from the night of Su’s fall: Tommy’s face, his freckles, what his back and shoulders looked like, the sounds of our captor’s body hitting the ledge and Tommy’s scream. After one particularly hard session, I felt like I had a concussion. I could see and hear my therapist talking to me. I felt myself pulling my keys out of my backpack, but I couldn’t understand or process her words. My brain had a hard time keeping up.Ěý

I thought I would have nightmares, but I didn’t. The next day I felt OK, and the next day, too. I realized that perhaps I was strong enough to confront this.

The future—mine, Theo’s, all of ours—is unknown. I train hard and climb as much as I can. My body’s tolerance for thin 5.14 cracks is less than it was. My sponsors, God bless them, have stuck with me and see my life as I try to see it myself: whole, textured, natural. I still have climbing goals based purely on difficulty. I’m sure I always will. But now, and I imagine for years to come, the one at the top of the list is to enjoy my time in the mountains with Randy and Theo. Theo just learned to spot, or at least he thinks he did, on the boulders in Camp 4. He reaches up his arms, his hands barely extending over his head, sure he has the strength to catch his dad if he falls.

, too, and the father of two small kids. I’m grateful for the years we spent growing up together. Without them I couldn’t have found the strength to pursue a life that is richer and more complex, even if at times the route is messy and hard. Many days now, Theo and I just drive down into the valley. We sit in the meadow beneath what he calls “El Tap.” Milkweed seeds blow in the wind, and Theo runs after them. He throws sand in the Merced River, and it floats away. Sometimes I can still feel the tape on my hands. I know how my body should move over the rock, but when I climb these days it doesn’t always go that way. When I’m honest with myself, I acknowledge that I still yearn for the accomplishment, the concrete proof that I’m doing it right.

But my Ziploc bags are now filled with crackers and grapes. They don’t stay in the right compartments of my backpack. Theo grabs them and they spill. When I’m looking at the granite walls, I try to remember that bravery is specific and personal, and that the kind of strength I want can’t be measured in pull-ups. Theo has already outgrown his first tiny pair of climbing shoes. I try to remember that I was never really in control.

Beth Rodden () blogs about climbing, motherhood, and adventure at . She wrote this story with şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř Contributing Editor Elizabeth Weil.