I am not a climber, a scientist, a mapmaker, or a former museum director. I have no first ascents to my name, nor have I led expeditions or tested gear for the military or been inducted into the Explorers Club. Bradford Washburn did all that, and more, with distinction. But for the purposes of this story, I couldn’t care less. What I care about is his photography—and how it is that Washburn, now 95, has created some of the world’s most spectacular images of mountains yet remains virtually unknown in the world of photography.

Bradford Washburn

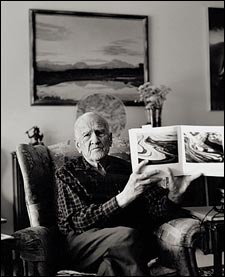

HAWK EYES: Washburn at home in Lexington, Massachusetts

HAWK EYES: Washburn at home in Lexington, MassachusettsBradford Washburn

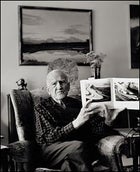

“THE SOUL OF THE ARTIST”: Washburn with his favorite “pattern pictures”

“THE SOUL OF THE ARTIST”: Washburn with his favorite “pattern pictures”Mine is a limited view to be sure, but—as a photographer myself—I take comfort in thinking I know quite a bit about pictures, who makes them, and the history of the medium. On the walls of my Montana studio are portraits of photographers, yearly added to through the generosity of my friend and colleague Bruce Weber, who surprises me at Christmastime with rare finds. When I opened Bruce’s gift four years ago, there was a book, Bradford Washburn: Mountain Photography, and a framed 1936 picture of Washburn, 26 at the time, wearing a head-to-toe sheepskin flight suit and holding a massive eight-by-ten camera. The images were stunning. Why had I never seen any of his work?

Bruce had provided the bait, and I was hooked. When I learned that Washburn was very much alive and active in the Boston suburb of Lexington—he drove his own car until this spring and still gives occasional talks—the snarly cub reporter who lives in a dark place inside me vowed to drag him into the photographic light of day by stripping away all the other hats he’s worn. I’d go to Lexington and make him confess to being something no self-respecting photographer should ever call himself: an artist. Even if I had to claw it out of his nonagenarian body.

THE RESEARCH I did prior to our meeting revealed that I was in for a fight. One interviewer described Washburn as “tough, gruff, and feisty.” “He is very purposeful,” said Tony Decanaes, 59, who wrote the text for the 1999 book Bradford Washburn: Mountain Photography and who shows Washburn’s work at his Panopticon Gallery, in Waltham, Massachusetts. “It’s instructive that he never went on an expedition led by anyone else,” offered David Roberts, a veteran climber, writer, and longtime friend of Washburn. Whatever the task, Washburn has been in control, the man in charge, and nothing about him or the way his life has unfolded seems accidental. Call it certitude. Call it fate. Call it a life of constantly pushing forward with a rare glance over the shoulder and few missteps.

Born in Boston in 1910, Washburn climbed his first peak—New Hampshire’s Mount Washington—at age 11. Two years later, his mother, an amateur photographer, gave him his first camera, a Kodak Brownie, the point-and-shoot of its day. When Washburn was 16, his father, an Episcopal minister, took the family on a six-month sabbatical to Europe, where the fledgling alpinist summited Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn. Not long after enrolling at Harvard in 1929, Washburn began lecturing at Carnegie Hall and the National Geographic Society about his climbs. He was just 21 when inducted into the Explorers Club. Seven years later, he began his museum career, not as an assistant but as director of Boston’s natural history museum, a post he would hold for the next 40 years.

Washburn evolved into a remarkably well-rounded explorer—a pioneer of geography, mountains, and aerial photography. Following his museum appointment, he led 16 research trips in the 1940s and ’50s, producing the first aerial images of Alaska’s great uncharted ranges, as well as Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn—all while notching first ascents and holding down his day job at the museum. He completed the first map of Mount McKinley in 1960, and spent the next 20 years producing aerial surveys of peaks in the Yukon, glaciers in Alaska, and vast tracts of the Grand Canyon. In 1984, he led the first photographic flights over Mount Everest, research that culminated in the first accurate map of the Nepal Himalayas. From these expeditions sprang a spectacular body of photographic work.

I had the chance to see it for myself on a brisk Sunday afternoon last fall. I’d traveled to Boston to view Colossal, an exhibition of 20 of Washburn’s supersize digital prints (approximately 40 by 60 inches) at the Panopticon Gallery, 15 minutes by car from the apartment he shares with his wife of 65 years, Barbara, in a retirement community on the outskirts of Lexington. A crowd of about 150 had gathered for this rare solo show by one of America’s finest living photographers.

A brief introduction was given by Tony Decanaes. Although Washburn spent nearly 80 years in the field, his images would still be virtually unknown to collectors if it weren’t for Decanaes’s inspired vision. The two met through a mutual friend in 1990, and Decanaes immediately sensed what they could do together. “Mountaineers knew about Brad,” he explains, “but outside of that sphere he was almost unknown. I saw those photographs and I knew this was an opportunity for Brad—and for me. I saw them big, and I saw them beautiful.”

When Washburn took the floor, wearing a suit and tie and armed with a laser pointer, my first impression was that he was shorter than I expected—somewhere around five foot seven—for someone who’d lugged 90-plus-pound packs across rivers and through countless miles of untracked wilderness as a young man. He has silvery hair, quick, hawk eyes, and a lean, slightly bent frame. Washburn directed the laser’s red dot to After the Storm: Climbers on the Doldenhorn, taken in Switzerland in 1960, and began tracing the footsteps of the six miniature climbers silhouetted on a snowy, cloud-shrouded ridge.

“I was in Switzerland working on a map,” Washburn said, projecting his voice past the front row to the back of the room, “and I asked them if there was anyone around here who had a small airplane. I’d never been up to take a look at the big Swiss peaks, particularly the Jungfrau. Someone answered that, yes, they do know a butcher who has such a plane. ‘He’s an honest-to-God butcher,’ they told me, ‘but he has an airplane just like the one you’ve been using in Alaska.’ “

Washburn was having his way with this bunch, serving up the kind of humor and understated derring-do that are implicit in trusting a butcher to escort you around the Alps’ highest peaks. “As we were approaching the Jungfrau, we had to make a sharp turn,” he continued, “and all of a sudden this picture was straight in front of my eyes!” Which is exactly how it felt to see it there—looming large in sharp, stark detail.

Describing an aerial he made of the Matterhorn in 1958, Washburn drew laughs when he recounted how you could stand on the summit and face a particular direction and pee one mile. This sort of dogged quantification is trademark Washburn. “Whenever I’d visit him,” David Roberts recalls, “he’d pull out something that he’d just written up, such as how many footsteps it would take to climb a certain route. He’s endlessly enthusiastic—it’s kept him alive for all these years—but he’s also one of the most obsessive people I know.”

Big mountains demanded big cameras, so Washburn—a compulsive problem solver—would remove the side door from the single-engine airplane and muscle his 50-pound Fairchild K-6 into position using a spiderweb of ropes, lashing himself to the bulkhead to keep from being sucked into the void. And in order to view his negatives in the field, he’d build his own backcountry developing tanks from three-gallon steel drums. In this way, he has spent his life straddling science and art, art and science—never fully realized in either. The moment he seemed comfortable in one role, he tackled another. And another.

“I LOVE SHADOWS, and I love haze!” Washburn announced the next day as I walked through the front door of his apartment. The hallway was dimly lit, and he had lunged out of nowhere, jabbing a finger in my chest. No “Good morning” or “How do you do?” “The early-morning haze is what makes it a good picture,” he explained, directing my eyes to a framed print of corniced ridges he’d titled Sunrise, Aiguille du Midi. “I was 19 when I did that picture, and I think it may be my best!”

Moving into the living room, we were joined by Barbara, who’d just turned 90 and had carefully styled hair and bold red lips. An avid adventurer in her own right—she was the first woman to summit Mount McKinley, in 1947—Barbara accompanied Washburn on many of his mapping projects. Anybody who has met her knows immediately this is a 50-50 deal. While Washburn may have lost a step or two over the years, Barbara’s mind is as agile as ever.

I assured him I wasn’t going to ask about what it was like to lead expeditions or make maps. All I wanted to discuss was his relationship to photography—starting with his 40-year friendship with Ansel Adams, whom he met through the Sierra Club in the thirties. But suddenly he leaped up, distracted, and rushed into his office to grab an eight-by-ten resin-coated proof print. “This is a picture somebody took from a U-2 spy plane,” he said, thrusting the photograph at me. “This is Mount McKinley taken from 68,000 feet. To me, it’s a really thrilling picture!”

“Now, Brad, just answer his questions,” Barbara said. She looked at me. “It’s not easy keeping him on track.”

“Barbara and I were invited to Ansel’s 80th birthday party in Carmel,” said Washburn, obliging. “We were two of eight people seated at the head table with Ansel. We’d never done anything like that before—travel all that way for a birthday party. I loved Ansel because of the real perfection in what he did.”

“Did you learn from him?” I asked.

“He taught me to expose for the shadows and develop for the highlights.”

I asked him if he’d read any of Adams’s how-to books on exposure, development, and printing.

“No.”

“Did you ever subscribe to photography magazines?”

“No.”

“No.”

“Did you collect books of photographs by other photographers?”

“No.”

“No.”

“Do you know the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson?”

“I don’t know anything about him.”

Here, then, was the disconnect. Washburn was a friend of Ansel Adams; he’d known the inventor of the Polaroid process, Edwin Land, and Harold “Doc” Edgerton, who pioneered stop-action strobe photography. He’d been blessed with enormous natural talent, had access to a community of photographers who were practicing the craft at its highest level, and had been included in a 1963 exhibition of American landscape photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. (“I thought his work achieved a very high standard of artistic power,” says John Szarkowski, MoMA’s former director of photography.) Yet all these years later, so few people in the world of photography know him or his work. Why?

For starters, he’s been busy. In addition to his many mapping expeditions, he spent nearly three years working for the Army during World War II, testing equipment in extreme conditions in Alaska. He and Barbara raised three children. And over the course of 40 years, he turned Boston’s stodgy New England Museum of Natural History into the dynamic, hands-on Museum of Science.

There has also been unfinished work to do. Soon after meeting Decanaes in 1990, Washburn showed him his portfolio. Though Washburn had exposed a stockpile of more than 15,000 negatives, he had but a handful of prints, few of which were exhibition-quality. “Is this all you have?” Decanaes asked. “You think I’m going to pay for prints only to put them in boxes?” Washburn responded. In the marketplace, the provenance of the print is like a purebred stallion’s bloodline, its traceable history. If a print was made close to when the photographer snapped the picture, it’s considered more valuable than a print made years later. If the photographer made the print—rather than a lab—better still; likewise if it was signed and dated, numbered or limited.

Together Washburn and Decanaes identified about 1,400 negatives for possible printing. Somewhere around 300 different images have been printed on traditional silver gelatin paper thus far, in sizes ranging from eight-by-ten to 20-by-24. There are about 3,000 signed, exhibition-quality Washburn prints of these 300-odd pictures in the Panopticon inventory, the sum of which represents the future of Washburn’s collectibility. And then there are his big digital images, created by scanning large-format negatives and printing them with archival inks on acid-free paper using ink-jet printers. The jury’s still out on how well these new inks will age, but there is no doubt that this technology is made to order for Washburn mountain photography. The clarity—you can see the fissures in the rocks, the texture of the snow—is captivating. And because ink-jet printing can remove scratches from field-worn negatives, the images appear as pristine as they must have looked to Washburn’s naked eye at the time of exposure.

“Although Brad pooh-poohs himself as an artist, if you look at his prints you realize they’re all full-frame and uncropped,” says Decanaes. “He has an uncanny instinct for composition. These are difficult prints to walk by.”

THE CRUX of Washburn’s photographic anonymity, as I’d come to see it, was that it had been too easy to dismiss his work as scientific documentation—simply the result of a persistent technician banging away at the landscape, with no vision or purpose other than research. All too often his pictures were used as examples of geological force and pattern, as illustrations in textbooks, as images overlaid with dotted lines tracing new climbing routes, such as the one he pioneered on the West Buttress of McKinley in 1951. Many top alpinists set off on expeditions with a Washburn contact print, a hand-drawn map, and a scouting report sent by Washburn himself. Seen this way, his photographs could be described as functional, a word that might apply if they weren’t—when properly printed and purely presented—so overpowering.

Likewise, it would be easy to think that Washburn’s peaks are so spectacular that any fool with a camera could get lucky now and then. The truth of the matter is that there are plenty of fools with cameras, but no one has yet in the history of photography made such compelling pictures of mountains. The Tairraz family of France spawned four generations of alpine photographers, including Georges, who did notable work in the Alps in the 1930s. Before him, Italian Vittorio Sella carried huge plate cameras in the Alps, Alaska, and the Himalayas in the late 19th century. Washburn knew of these men, and they were influential in his decision to use large-format cameras. Although the late Galen Rowell, who was Washburn’s friend for almost 40 years, was himself an accomplished climber and a truly fine photographer of mountains, his most memorable work was made while on the peaks, not in the air around or above.

Only in Washburn’s pictures are mountains seen whole, as individuals highlighted in a community of mountains. He has made portraits of mountains, endowing them with singularity and personality. In his preface to Mount McKinley: The Conquest of Denali (1991), Ansel Adams writes of Washburn’s work, “The photographs look almost inevitable, perfectly composed.” Through a simple purity that arose out of reverence, honesty of intention, technical competence, and passion, Washburn created photographs that reveal not the maker but what legendary photographer Edward Weston described as “the thing itself.”

“Washburn is one of the few who has been able to make great science and great art,” says Donald Smith, author of the 2002 Washburn biography On High. “His pictures are pure genius, but he doesn’t know why. . . . He just has the soul of an artist.”

MORNING LIGHT FILLED Washburn’s living room. Scattered around us on the floor were dozens of sheets of paper: correspondence, current projects, ongoing business. (One of his latest endeavors, Washburn told me, was mapping his retirement community.) From time to time, he shuffled the papers into various piles with his feet, saving him the effort of bending over. On walls and tabletops were memorabilia from awards given, expeditions led, milestones of a life lived fully. Notably, only a few photographs were framed and hung.

I pushed myself to the edge of the sofa, winding up for my final question. “Were any of the photographs in the Panopticon show taken initially for mapping purposes?” I asked.

“No,” he told me, “mapping pictures are made through a hole in the bottom of the airplane. It’s a mechanical kind of thing.”

Eureka! “So these pictures you did out the door weren’t for scientific purpose. You’re an artist in that airplane, aren’t you?”

Washburn seemed stunned, as though it had taken nearly a century to crack this nut. “Maybe,” he said, thinking it over. “I was interested in bringing to other people the thrill I was getting when I saw the scene.”

Maybe. Considering how few maybes there have been in Washburn’s life, this concession is huge. Even now, he is resisting labels, defying categorization. Looking at his pictures, however, one thing is certain: He loved the mountains, and they loved him back. Colossally.