It’s an unavoidable truth: our heroes don’t always come home alive—and they leave behind more than unforgettable stories. Here, those closest to six departed icons share their most cherished relics.

Isaac and Sam Lowe-Anker and Max Lowe

With Alex Lowe's hat, ice ax, and truck

Isaac: “The hat I'm wearing is my dad's. Mom knit it for him when they first met. He wore it on all of his expeditions except his last one. It was finally starting to tear, so he didn't want to take it with him.”

Sam: “I'm holding his ice ax. It's interesting having a celebrity father. People know us through that, and at climbing events people sometimes stare at us like, Wow, you're the offspring of Alex Lowe.”

Max: “He was very passionate about music, and he insisted that I learn to play the violin. He would never push me to climb, but whenever I wanted to go out climbing or skiing he would be really excited. He wanted us to have passion in life—whether it was the same passion he had didn't matter.”

In 1999, Alex Lowe, 40, was killed in an avalanche while scouting Tibet's 26,289-foot Shishapangma. His body was never recovered. Isaac, 14, is a freshman in high school; Sam, 18, is a freshman at Montana State University; and Max, 22, is a senior at Westminster College in Salt Lake City.

Willie Kern

With Chuck Kern's kayak and paddle

“Fourteen years later, what did I keep? That squirt boat and paddle—those are the things I couldn't get rid of. They're like museum pieces, a testament to the time when kayaking went through its greatest revolution. My brother was at the forefront of that. Most of the squirt boats of that era were custom-made. On the inside, there's a label that says made for chuck kern with his weight and the performance he wanted. He was my older brother, and we shared tens of thousands of river miles. The Black Canyon, where he drowned, had been paddled a long time, and there's a very traditional portage route. But the way things had been done historically was not necessarily how we wanted to do them. We wanted to stay at river level and paddle as many rapids as we could. If there was a road next to where he died—if I could have taken out of the water right there—I may have quit paddling altogether. But we had to get out of the canyon, and I went through the whole range of emotions on the seven-mile paddle out. By the time I'd made it to the takeout, I realized that his death was just the ultimate consequence of what we were doing. I could accept that. If I had stopped kayaking after he died, I would have been disrespecting his legacy.”

In 1997, Chuck Kern, 27, was pinned in a sieve and drowned while attempting a section of Colorado's Black Canyon of the Gunnison River with his brothers, Willie and Johnnie. His boat and body were recovered two days later. Willie Kern, 39, is a professional kayaker.

J.T. Holmes

With Shane McConkey's Pontoon skis

“Shane had persistence. Whenever he got an idea, it was like, “We're going to figure this out.” With the Pontoon skis, which he designed, his epiphany came from watching water-skiing. It dawned on him that powder is softer than water. So he actually mounted some water skis and took them out on snow. It was the same thing with ski-BASE jumping. The first time we did a ski-BASE was in South Lake Tahoe in 2003. It was like we had new eyes, looking at the mountains. Nobody else was seeing the same lines we were. When he died, I did take a pause. I debated whether I could continue—or even wanted to. There was no craving. But after a few months, I got the urge. That first jump back felt great, like it always had. When I was 15 and Shane was 25, we ducked a rope and skied out of bounds together. I asked, “Hey, man, what do you do for money?” He looked at me with this grin on his face and said, “I'm a rock-star pro skier, man!” He was so happy. I knew right then that's what I wanted to be.”

In 2009, McConkey, 39, died while attempting a ski-BASE jump in the Italian Dolomites. Holmes, 29, who had jumped just ahead of McConkey that day, is a professional skier.

Alicia Shay

With Ryan Shay's bible

“The bible was something that held us together. When you lose someone who has become part of who you are, it is unspeakably difficult to get up every day and put one foot in front of the other. I couldn't have done it without God's help. I met Ryan at the New York City Marathon in 2005. I knew pretty quickly that we would spend our lives together. We were both trying to make the Olympic team. Had it not been for him, I would have quit running. He helped me through an injury and refined what I thought I was capable of. He did that for everyone. Ryan was almost like a big brother to the running community, and we've all shared the grief of losing him. But I'm ready to start running again. I feel good, like my old self. And given everything that's transpired in New York, from meeting the love of my life there to losing the love of my life there, I want to face that race again.”

Ryan Shay, 28, died from a heart arrhythmia while competing in the 2008 Olympic Trials, held in New York City the day before the 2007 marathon. Alicia Shay, 28, who'd married Ryan four months earlier, is once again pursuing a career in professional running.

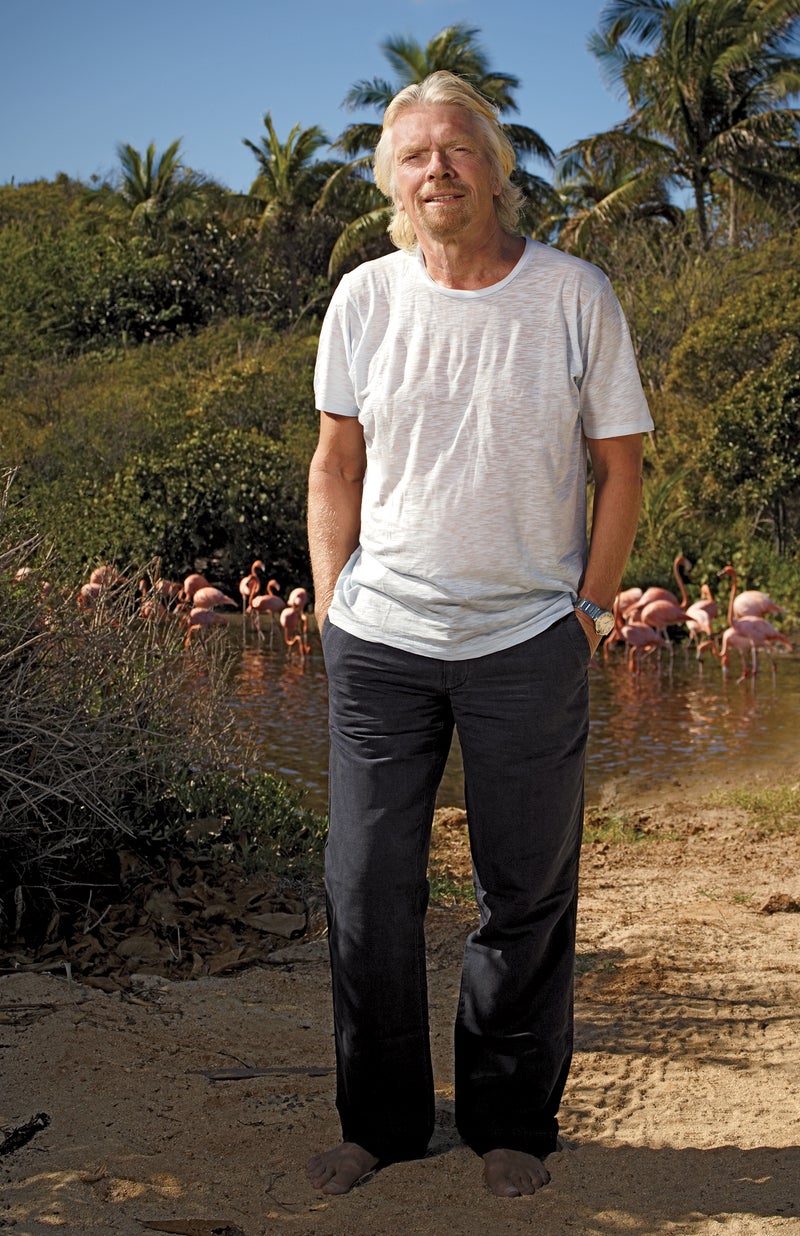

Richard Branson

With Steve Fossett's flamingos

“In the race to claim the first round-the-world flight in a balloon, we were rivals, but friendly rivals. During one of Steve's attempts, he crashed in the Pacific and nearly died. I was getting close to taking off from Morocco in a three-man capsule, so I rang him to see if he would like to join us. We became good friends while flying together those seven days: crossing Mount Everest and down the Himalayan chain, with the Chinese threatening to shoot us down. During the trip, I talked with him about my desire to repopulate Necker Island with flamingos, because they had been wiped out from the British Virgin Islands 100 years ago. After he flew nonstop around the world in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, the first plane to do so, he gave me the flamingos as a gift. From the original flock of ten, we now have 250 breeding birds. We're actually using those to populate other islands. If future generations come to the British Virgin Islands and see a flamingo, they'll be able to thank Steve Fossett.”

Fossett, 63, died in California's Sierra Nevada in a plane crash in 2007. Branson, 60, is the president and founder of Virgin Global, which includes Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Galactic.

Allen Sarlo

With Mark Foo's surfboard

“Mark always kept a surfboard at my house in California, just like I stored boards at his house in Hawaii. After he died, I inherited his Todos Santos board, which is made for riding giant surf. It has the word foo painted on it. It reminds me of him because he was fearless in the water. He was a little flashy and brash, but he could always back up his talk. He took off deeper than anybody. If I did three turns on the wave, he'd do four. We were friends for almost 20 years and owned a place together right on Waimea Bay. We were there the night before he died. We'd been surfing Waimea all day, and he said, “Allen, I'm going to Maverick's. The surf is going to be great. I'll be back for Christmas.” He was a pioneer of forecasting and chasing swells. He'd always been fascinated by hitting a swell in Hawaii one day and then flying to California and catching it at Maverick's the next. I was lying on the couch half asleep, and he was packing his boards. I remember waving goodbye and saying, “OK, I'll see you in a couple days.” That was the last time I saw him alive.”

In 1994, Foo, 37, drowned while surfing Maverick's, presumably after his leash caught on rocks underwater. Sarlo, 53, a prominent member of the original Z-Boys surf and skateboard crew, is a real estate agent in California.