On a cold Wednesday evening in December, the Big Bear Lake Performing Arts Center is crawling with kids. It’s Warren Miller movie night in Big Bear Lake, a mountain burg above Los Angeles, and a scrum of local grommets, all shaggy hair and Hurley caps, are bouncing in their seats like monkeys on Red Bull.

Johnny Collinson

17-year-old Johnny Collinson on Mount Elbrus, July 2009

17-year-old Johnny Collinson on Mount Elbrus, July 2009Samantha Larson

Samantha Larson, at age 18, on Everest in 2007

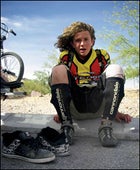

Samantha Larson, at age 18, on Everest in 2007Jordan Romero

“Dude, Chargers are the best. Raiders suck.”

“Raiders suck!”

“Ew, dude, what’s that on your shoe?!”

“Parker! Sit over here!”

In the midst of this attention-deficit festival, a tall, quiet kid makes his way down the aisle, stopping to talk to adults along the way. He has a shy smile and almond eyes that peek out from behind a parted curtain of wavy brown hair. His name is Jordan Romero. He is 13. In May, he plans to become the youngest person ever to climb Mount Everest.

If he makes it, Jordan could be one of the most famous kids of his generation: the Boy Who Climbed Everest. With more and more of his peers playing video games, fighting obesity, and contracting diabetes, he would serve as a powerful counterexample. He wants to inspire American kids to climb their own mountains. Or at least to go outside.

On this night, though, Jordan is hoping to inspire his neighbors to contribute some coin to his quest. It will cost Jordan about $40,000 to climb Everest, and his rope team also includes his father, Paul, 40, and Paul’s partner, Karen Lundgren, 44, both pro adventure racers. Team Romero, they call themselves, and Everest is only a part of their goal. If Jordan can climb Everest and Antarctica’s Vinson Massif, he will become the youngest person to have climbed the Seven Summits, the highest points on each continent. Few people have ticked their seventh peak before their thirties. Jordan could do it before he learns to shave.

The lights dim. An image of Jordan fills the screen. “We had a local filmmaker put this together,” Paul whispers. “I haven’t seen it yet.”

The voice-over begins. “At 13 years of age, Big Bear’s Jordan Romero has already accomplished what many experienced mountaineers three or four times his age can only dream of doing…When he was nine years old, Jordan was inspired by a school mural of the Seven Summits and told his father, Paul, he wanted to go for it. Paul Romero, a life-flight medic and adventure racer, along with his partner, Karen Lundgren, were the perfect coaches to make Jordan’s dream come true.”

They haven’t wasted much time. When Jordan was ten, he and his folks climbed 19,340-foot Kilimanjaro (Africa), 7,310-foot Mount Kosciusko (Australia), and 18,510-foot Mount Elbrus (Europe). At 11, he set the age record on 22,834-foot Aconcagua (South America) and climbed 20,320-foot Denali (North America). Last year, he climbed Indonesia’s 16,023-foot Carstensz Pyramid, the highest point in Oceania and the so-called “eighth” summit. That leaves Antarctica’s 16,067-foot Vinson Massif and 29,035-foot Everest.

The narration rolls on: “Jordan’s motto, Ad alta (‘To the summit’), captures the spirit of his journey…The importance of setting and reaching goals, living an active and healthy lifestyle, and being a wholesome role model for other kids are key elements to his quest.”

Paul Romero likes what he sees. “Great work,” he says at the film’s end. “Awesome.”

Jordan hops up onstage to tell the crowd about a local get-out-and-hike campaign he’s spearheading. “First of all, I want to thank all of you for coming out,” he says. “Anyway, what I want to talk to you about is the Seven Summits Youth Challenge, which is a challenge to all youth to hike the seven highest mountains in the Big Bear area.”

He’s a bit bashful, and he’s swimming in an oversize button-down. But the crowd cheers and Jordan flops back into his seat, relieved that his part is over. His buddies razz him a bit. Then the Warren Miller movie starts and he returns to the anonymous role of just another kid stoked on powder porn.

In many ways, Jordan is just a normal kid. In some ways he’s not. Or perhaps that’s missing the point. Maybe Jordan Romero is what 13 could be.

Wait. Thirteen? On Everest?

Actually, yeah. A new phenomenon has emerged in the adventure world: kids posting monster feats. On water, the record smashing has turned into an age relay, with ever-younger sailors leaving port as the previous record setter ties up at the dock. In 1968, 29-year-old British sailor Robin Knox-Johnston completed the first nonstop solo circumnavigation of the globe. Last year, two 17-year-olds, American Zac Sunderland and Brit Mike Perham, each repeated the journey. Australian Jessica Watson, 16, is midway through her own solo sail, and Zac Sunderland’s 16-year-old sister, Abby, shoved off in January, intent on beating her brother’s mark.

Something similar is happening in the mountains. For years after ski-resort impresario Dick Bass created the continental-tick-list craze in 1985, the roster of climbers who completed it read like an alpinist all-star team, from the incomparable Reinhold Messner to legendary New Zealand guide Rob Hall. Today there are climbers who can include the Seven Summits on their college applications. Three years ago, 18-year-old American Samantha Larson stood on the summit of Mount Everest. She didn’t beat the age record held by Ming Kipa Sherpa, the Nepalese girl who summited at 15, in 2003, but she did wrest the “youngest Seven Summits climber” title from Rhys Miles Jones, a Brit who’d bagged his final peak at 20.

So many teenagers showed up at Everest’s south-side Base Camp last spring that they were dubbed the Brat Pack. There was Johnny Strange, an intense 17-year-old from Southern California; Johnny Collinson, a 17-year-old ski rat from Utah; and Erica Dohring, a 17-year-old climber from a Phoenix suburb. Dohring turned back during her summit push, but the two Johnnys leapfrogged each other on separate expeditions, topping out within 24 hours of one another. A few weeks later, Strange tagged Australia’s Kosciusko as the final peak in his Seven Summits bid, stealing the “youngest” title from Samantha Larson. Collinson went on to climb his own seventh summit in January. Though he wasn’t the youngest, he added a twist: He climbed all seven in a year. (Well, 367 days.)

All this kid stuff is raising eyebrows in the adventure community and sometimes the legal community as well. Polling a number of well-known Everest climbers and guides, I couldn’t find one who thought that leading a 13-year-old up the world’s highest mountain was a particularly good idea. Though a climber that young might possess the necessary stamina, most had serious reservations about a teen’s emotional strength, psychological awareness, and plain old know-how.”I do not see how young people under the age of 18 can gain enough experience about mountaineering or themselves to undertake such a project safely,” said Russell Brice, one of Everest’s most successful guides.

Elizabeth Hawley, the Kathmandu-based climbing historian, isn’t in favor of age limits. But she said of last year’s 17-year-olds, “This is too young an age to be climbing huge mountains.” Teenagers’ physiques aren’t fully formed, she told me, “and equally if not more importantly, their judgment and reflexes based on experience have not had time to be well developed.”

Last year, similar concerns led Dutch authorities to ground Laura Dekker, a 13-year-old who wanted to sail around the world solo. Dekker’s desire, and her father’s willingness to let her go, touched off an international ruckus over the boundary separating bold adventure from child endangerment. In the Netherlands, at least, the legal line was drawn. In October, a Dutch court put the girl under temporary guardianship. (She still lives at home but must get permission to set sail.) The Dekkers have appealed, hoping that Laura can still beat the age record.

American courts have shown no inclination to go this far, and Jordan’s mother, Leigh Anne Drake, a teacher and ski patroller who shares custody with his father, supports her son’s ambition. “When I think about Jordan on Everest, it cuts my heart in half,” she says. “I can hardly breathe when I think about the risks. On the other hand, I’m overwhelmed with excitement about the opportunities his climbing has brought him. He’s been exposed to the world, and he’s grown so much as a mature young person because of it.”

But if something goes wrong for Team Romero on Everest and let’s face it, it’s Everest; anything can happen the outcry could dwarf all that we’ve seen after past climbing tragedies. An adult who dies climbing may elicit a disapproving tsk-tsk from the nonclimbing world. A kid’s death could draw Nancy Grace and a passel of outraged congressmen into the fray.

“What these kids are doing isn’t necessarily a bad thing,” says Todd Burleson, whose company, Alpine Ascents International, guided Johnny Strange on Vinson. “But as soon as you start burying kids on Everest, it’s going to be a different story. And if enough of them start going up there, it’s going to happen.”

Team Romero Trains Hard to make sure it doesn’t. Jordan thinks about Everest all the time. He trains every day. Ice axes are mounted on the wall of his room, along with a poster of Ed Viesturs and a giant map of the Big E. The family has two $4,000 hypoxic tents, borrowed from a friend, to approximate the effects of sleeping in thin air.

In January, Jordan switched to an independent-study program so he could train more during the daytime and study at night. They will leave for Everest in April, with an eye toward summiting in early May from the northern (Tibetan) side instead of the more common southern (Nepalese) route.

“Karen and I went over there last May to climb Nuptse,” a 25,790-foot peak next to Everest, says Paul. The pair stopped 1,000 feet shy of the summit, which was OK with them; they had come largely to research the Everest route, which Nuptse climbers use before forking off at 24,000 feet. “I learned one thing,” Paul says. “The Khumbu Icefall is a place I never want to visit again. It was like playing Russian roulette. We had giant serac collapses. Someone died. That convinced me I didn’t want to take Jordan on the standard route.”

Instead they’ll take on the exposed rock and vertical wall of the Northeast Ridge. Going that way saves money, because the Chinese permit is cheaper and it also skirts Nepal’s age requirement. Ten years ago, a 15-year-old Nepali boy, Temba Tsheri, lost five fingers during an Everest attempt, prompting the government to prohibit climbers under 16. China has no such rule.Aside from Jordan’s age, the most controversial aspect of Team Romero’s Everest attempt is this: They’ll climb without a guide.

“So far we’ve done all our climbs that way, except Kilimanjaro, where you’re required to hire a local guide,” says Karen. “We climb like we race very light, taking only what we absolutely need. And there’s no one there to tell us Jordan’s too young.”

It’s a self-reliance born partly of necessity. Professional guides would double costs and break Team Romero’s limited budget. At least a dozen corporate sponsors including Sole footbeds, Vasque boots, Jetboil stoves, and FRS energy drinks are contributing equipment, and Jordan recently won a $5,000 Polartec Challenge grant. But most of the $120,000 expedition total is coming out of Team Romero’s life savings.

Paul and Karen believe their experience as adventure racers will help them with endurance, rope handling, and decision making. In addition, Paul brings the medical expertise of a professional flight medic.

“We’ll come in acclimatized, having been in our hypoxic tents for five weeks at Big Bear’s altitude of 7,000 feet,” says Paul. “So we don’t have to climb high and sleep low. We’re going to climb as little as possible, reserve our energy, avoid wasting time.”

That seems logical enough, but some Everest veterans are skeptical about the benefits of hypoxic tents. And their lack of experience Nuptse is Paul and Karen’s only Himalayan foray, and Jordan has never climbed above 22,834 feet is troubling. “I would be concerned for the others who are around that climber,” says Russell Brice, “and for sure I would try not to have my team going to the summit on that same day.”

If Jordan does summit, he’ll be the only teen to do so without a pro on the short end of the rope. Even 15-year-old Ming Kipa Sherpa climbed with her older sister Lhakpa, who had summited Everest twice. Last year’s teens were each partnered with an experienced guide: Scott Woolums (with Johnny Strange), Damian Benegas (with Johnny Collinson), and Dave Hahn (with Erica Dohring). It took the seasoned eyes of Hahn, who has been up Everest 11 times, to recognize that Dohring was climbing too slowly to summit and survive. He felt comfortable leading Dohring because he’d worked with her on Denali. But guiding a 13-year-old, he says, “is not something I would want to be involved in. It’s too dangerous.”

Team Romero aren’t going completely on their own. Sherpa ���ϳԹ��� Travel, a Kathmandu-based outfitter, will provide them with base-camp facilities, food, oxygen, and three climbing Sherpas for the summit attempt. Such support-and-Sherpa packages are common now on Everest, with some outfits asking as little as $28,800, instead of the $65,000 a full-service operator may charge.

“Because there’s a high level of safety and success with the better Everest operators,” says Guy Cotter, director of the guide service ���ϳԹ��� Consultants, “it’s easy for people to think climbing Everest isn’t that hard or dangerous. But many expeditions that rely primarily on Sherpa support fail unless the Western leader has a lot of experience putting together an 8,000-meter ascent.”

A few years ago, Cotter worked with Chris Harris, an Australian kid who, at 12, set his sights on the mountain. Cotter’s guides brought Harris up through progressively more challenging climbs, and in 2006, at age 15, he declared himself ready. A summit climb would have made him the youngest person to stand atop Everest. Cotter said OK, but only if Harris and his father climbed “private,” i.e., hired a guide dedicated to them alone. The Harrises balked. “They didn’t really grasp that when taking very young climbers onto Everest,” Cotter says, “you have to cover your bases and provide a sufficient safety net to deal with any eventuality.”

The Harrises, in fact, barely skirted tragedy. They signed on with 7 Summits Club, an à la carte Russian service whose clients included German climber Thomas Weber, who died near the summit, and Lincoln Hall, who was given up for dead before being rescued by a separate expedition the next day. Altitude sickness cut Chris Harris’s climb short, perhaps fortuitously.

The Romeros have run into skepticism before. When Jordan was 11, they had to obtain a court order in Argentina to allow them to climb Aconcagua, which has a strict age requirement of 14.”I know that criticism is out there,” Paul says. “I cannot waste my time with it. I think about it, of course. It’s one of the last things I think about at night when I lie in bed. Karen and I weigh that all the time. And I feel as strongly confident as ever, watching Jordan and the team develop. On a physical level, Jordan is getting so strong. That’s 5 percent of what matters on Everest, of course.”

It’s the other 95 percent that’s worrying.

The Romeros live in a suburban rambler dappled by the shade of ponderosa pines. When I drop by the day after movie night, the place is a whirl of activity. While Jordan sits in his eighth-grade class at Big Bear Middle School, Paul unpacks from the family’s recent trip to South America, where they competed in the grueling adventure race Ecomotion Brasil.

“We came in third, which was a bit of a disappointment for us,” he says.

Paul is a perpetually sunny and ridiculously fit guy, with the long, lean physique of a climber. He’s rocking a Bluetooth and swathed in logo’d racing swag. Paul speaks like a man who’s had auto detailers work over his brain to remove any residue of pessimism and self-doubt. His answering machine encourages callers to “Go fast, take chances!”

Karen sits at a laptop in the kitchen. Behind her hang four clocks set to local time in Beijing, São Paulo, Christchurch, and London. On the living-room wall are more than a dozen summit photos and magazine covers, including the kid favorite Weekly Reader. A poster-size Jordan, posing in full gear on a studio mountaintop, hangs by the front door.

As Paul yaks into his Bluetooth, a feeling of déjà vu rushes over me. It takes a second, but I finally realize what it is: the sensation of stepping into a Wes Anderson movie, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou or The Royal Tenenbaums, in which strange, all-consuming passions are treated with the nonchalance of ordinary life. The Life Adventurous with the Family Romero.

“Karen, do you know when J. gets home?”

“It’s a half-day. I think around noon.”

The clock set to local time reads 12:15. “Wonder what’s keeping him,” says Paul.He and Karen discuss Jordan’s afternoon regimen. “I was thinking we’d do some tire pulls, maybe some snowshoeing and cycling around the lake,” says Paul.

“We need time to go over his speech to the Rotary Club tonight,” Karen reminds him.

At 12:45, Jordan lumbers up the driveway. With his shaggy hair, cocked baseball cap, and slumping gait, he’s all eighth-grade boy.

“What’d you learn today?” asks Paul.

“Stuff.”

Paul presses. “Tell me one thing.”

“We learned about atomic reactions.”

“What about atomic reactions?”

“That you wouldn’t want to be around when one happened.”

His dad smiles. Score one for the kid.

Paul lays out the afternoon’s plan. “How many tire pulls you think you should do today?”Jordan mulls it over. “Um, five?”

A long pause. “It’s been a while,” Paul says.

Jordan gets the hint. “OK. Ten.”

After a quick change into workout gear, Jordan shoulders a backpack weighted with rocks and clips his climbing harness to a BF Goodrich Traction T/A radial. He drags the tire to the bottom of the 400-yard hill in front of his house, then huffs to the top. He turns around and does it again. And again.

“What goes through your mind as you do this?” I ask.

“I just think about how it’s making me stronger,” he says.

He’s on his eighth pull when Karen calls him in. “Time to quit, Jordan!” she says. “Your dad’s got a turkey sandwich for you.”

In the kitchen, Jordan wolfs the food down. “How your legs feel out there, J.?” Paul asks.”Good,” he says. Then, louder: “Strong.”

“Good boy,” says Paul.

When Jordan heads back out for a seven-mile bike ride, Paul and Karen and I talk by the fire. “This is Jordan’s deal,” Paul assures me. At first, he talked about it as something to do later in life, but the more the family discussed it, the more they thought: Why not now? “We regularly check in with him to make sure this is really still what he wants to do,” Paul says, “that he’s enjoying it.”

A few people I talked with in the adventure-racing world wondered about Jordan’s motivation. Does the kid really want to do it, or is his hard-driving father taking his own love of adventure (and perhaps his ego) to a dangerous extreme? “Jordan’s dad is a little wacky, a little…intense,” says one climber who’s worked with the family. It’s true. In person, Paul radiates a kind of kooky energy, though it seems to be well partnered with Karen’s thoughtful, grounded presence.

“This was never to be a crazy dad boosting my ego or fame on my son’s accomplishments,” Paul insists. “We’ll bring him in and ask him with you here, if you’d like.”

This is a little too Captain von Trapp for my taste. “No need,” I say.

Later, when Paul steps out of the room, I ask Jordan how he answers the question, Aren’t you a little young for Everest?

“Other people’s doubts just make me stronger,” he says. “I’m determined to prove them wrong.”

I ask what he most enjoys about his quest. “Where do you find the pleasure in it?”

“I just focus on the goal I set out when I was nine, which is to climb the Seven Summits,” he tells me. “I’m just not giving up. Stopping at nothing. I don’t let people’s doubts bring me down.”

There’s a ghost that haunts these youthful dreams: Jessica Dubroff.

Jessica was a seven-year-old California kid who dreamed of becoming the youngest person to fly across America. In April 1996, while still a pilot trainee and still seven she took the controls of a Cessna 177 Cardinal and launched near San Francisco, accompanied by her dad and her flight instructor. She needed a booster seat to see through the windshield.

As Jessica and her chaperones hopscotched east, media attention snowballed. Then disaster struck. In Cheyenne, Wyoming, she took off in a heavy rainstorm. The Cessna stalled and crashed just after takeoff, killing everyone onboard. A cute feature about a plucky little girl curdled into a blamefest. The FAA will no longer grant full pilots’ licenses to anyone under 17.

The combination of record setting and high altitude could make for a similarly tragic mix. Age records have a built-in deadline: Either you grab the ring by a certain age or you don’t. That’s precisely the wrong attitude to take into the Death Zone.

The Romeros have heard all this before. “It really doesn’t matter what age you are,” Jordan says. “I’m a very strong person. When I go into the mountains, I’m physically and mentally prepared.”

His father agrees: “It’s what’s between the ears that matters.”

Maybe so, but what is between teen ears? Society sets all sorts of developmental boundaries around kids. In most states, they can’t have sex until they’re 16. They can’t join the Army until 17. At 18, they can vote, buy cigarettes, and be sent to adult prison. At 21, the gate opens to sins of the highest threshold: gambling and booze. Those aren’t arbitrary numbers. They’re set by a common understanding of psychological maturity. All 15-year-olds have the ability to smoke, drink, and roll in the hay. They just might not have the marbles to handle it.

Few studies have been done on kids at altitude, but what science can tell us is this: The teenage brain works differently. In the past decade, MRI technology has shown that the adolescent brain is only about 80 percent developed. The areas that control spatial, sensory, auditory, and language functions are mature, but the frontal lobe, which handles reasoning, planning, and judgment, isn’t fully grown until a person’s mid-twenties. “It’s not a lack of worldly experience,” says Dr. Lynn Ponton, a San Francisco based psychiatrist and the author of The Romance of Risk: Why Teenagers Do the Things They Do. “It’s the physical development of the brain. Some of these kids may have climbed ten mountains, but they still don’t have the capacity to make sophisticated decisions or choices. And it fools people. Their parents will think, They’ve done this and that they’re ready for the much bigger challenge. But the kid’s brain is still developing.

The other issue is the effects of altitude on those maturing brains. “Thirteen-year-olds on Everest are guinea pigs,” says R. Douglas Fields, chief of nervous-system development at the National Institutes of Health. “The combination of factors experienced in mountaineering hypoxia dehydration, exhaustion, cold, lack of sleep, and all the rest make it difficult to say how a child’s brain would be affected.”

One recent study by a Spanish researcher, Fields wrote in ���ϳԹ��� last October, suggests that climbers at high altitude suffer more brain damage than previously assumed. But an earlier study indicated that young people were at decreased risk for some of that damage. For now, no one really knows, but Fields has agonized about high-altitude climbing with his own children. “I understand the reward and risk issues very well,” he says. “But Everest is different.”

SO WHERE DO WE draw the line? To help find out, I track down Johnny Strange and Johnny Collinson, the elders from whom Jordan is attempting to wrest the title of youngest Seven Summiteer.

I find Strange at his dad’s beachside house near Malibu. Now 18, he lives the life of a teen action hero. He’s got the body of a UFC fighter and the chiseled mug of an Abercrombie & Fitch model. And he’s got something to prove. “When I was in fourth grade, my teacher told me I’d never amount to anything,” he says. “I was like, OK, watch me.”

At 12, Johnny talked his way onto a Vinson Massif expedition organized by his father, Brian Strange. “It took some doing to convince the outfitter to let us bring him along,” recalls Brian. “To be honest, I didn’t think he’d make it to the summit.”

Guide Vern Tejas, who led the climb, took extra precautions. “I usually don’t have adult climbers rope up on the summit ridge,” he says, “but I tied myself to Johnny, mostly for my own peace of mind. I didn’t know what the world might think if anything went wrong.”

As it turned out, Strange’s physical capabilities were the least of the expedition’s concerns. Risk liability, however, was an issue. In fact, Antarctic Logistics and Expeditions, the Salt Lake City based company that operates charter flights to Antarctica, was already formulating a new policy. Minimum age: 16.

Here’s the biggest surprise about Strange: Now that he has the record, he doesn’t want it. “I hope Jordan breaks my mark,” he says. “The thing about the Seven Summits and the youngest records is, I’ve been around enough real climbers now to know that they aren’t important. Telling Scott Woolums” his Everest guide “that you’ve done the Seven Summits isn’t going to impress him.”

“When I was 13, I wanted to climb Everest,” he says. “There was a reason I didn’t. I wasn’t ready for it. At that age, I would’ve climbed K2 if you let me. And I would’ve died. You’ve got to be careful. You’ve got to remember that at 13 you’re still talking to a kid, no matter what his physical abilities. I’m 17 and I still think I know it all and at the same time I realize I don’t. At 13, you just don’t have the ability to employ logic, complex reasoning, and weigh consequences in high-risk situations.”

There is a similarly reflective mind at work in Johnny Collinson. Collinson was born to the mountain life. His dad, Jim, is the snow-safety director at Snowbird ski resort, outside Salt Lake City. When Johnny was a tot, his family spent every summer vagabonding around the West in a blue Econoline van. The boy climbed Mount Rainier in 1996. He was four. He weighed 32 pounds.”Some people thought it was great,” Jim recalls. “Others thought they ought to call the child-protection agency.”

By the time he was seven, Johnny had compiled the climbing résumé of a middle-aged man, with summits of Rainier, Whitney, Shasta, Adams, Hood, St. Helens, Baker, and 30 of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks.

His Seven Summits bid started as a lark. Two years ago, he went through a rough patch. He struggled in school, didn’t get his driver’s license on time the usual teenage woes. At the same time, one of Jim Collinson’s fellow ski patrollers Willie Benegas, 41, one-half of the Benegas brothers, Argentinian twins known for their speed ascents of the world’s toughest peaks was prepping for the Wasatch 100 endurance race. Willie and Johnny began training together; for their first outing, they set off on a night run in the middle of a storm, finishing 25 miles later at dawn. “We made a connection,” Willie says. “He is one of the few people who can move as fast in the mountains as Damian and me. And his level of suffering is as high as mine.”

The brothers took on Johnny as a Benegas-in-training. “I learn something new on each mountain,” Johnny says. “Aconcagua was my first big mountain, my first time on my own in a foreign country. Denali was sheer grunt work, with me and Damian hauling our own gear. Everest was mentally taxing; so much teamwork and logistical planning went into the effort.” By the time they tackled Everest, Johnny was more team member than client.

After talking with the two Johnnys, it occurs to me that the gap between 13 and 17 comes down to this: brainpower. Strange and Collinson each possess the cognitive ability to apply abstract ideas to real-world experiences, to reflect, to analyze, to go meta on a situation. They know what they don’t know.

Thirty years ago, there were no Everest guides, no Seven Summits expedition packages. Back in the 1970s, when Peter Whittaker, now the owner of Rainier Mountaineering Inc., climbed Rainier, at age 12, he knew he was the youngest because the old-timers in the guide shack told him so. Peter’s father and uncle were Himalaya pioneers Lou and Jim Whittaker, but even for them, taking a teenager up Everest would’ve been absurd.

Today, every record is available at the click of a mouse, every climb is bloggable, and every Seven Summits project turns into a record-setting quest. The more audacious the record, the more attention it attracts and the more value it delivers to sponsors, which in turn makes the audacious record chase financially possible. (I’m not unaware of the role this magazine and I play in the cycle.)

There’s another element to this as well. Psychologist Richard Louv coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” in his 2005 book Last Child in the Woods. The area in which American kids are allowed to roam, he wrote, shrank by 89 percent between the 1970s and the 1990s. Not long ago, up to three-quarters of all kids walked or biked to school. Now, fewer than one in five do. In the 1960s, fewer than 5 percent of American children were obese. Now that figure is pushing 20 percent.

Louv is intrigued by this new crop of Iron Kids. “I wonder if it’s a reaction against the constraints we’ve put on our children,” he says. “It’s almost as if we’ve bifurcated the experience of playing outdoors. Either you stay inside, or you become one of these superkids who go after extreme experiences in the outdoors. The problem is that there’s very little in between.”

Some statistics seem to bear out his theory. A recent study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation found that American eight- to 18-year-olds average seven hours 11 minutes a day in front of the TV, video games, or computers. At the same time, kid participation in endurance events is booming. USA Triathlon, the sport’s main sanctioning body, had 16,320 youth members in 2007. Last year the number hit 31,259; 15,784 of those budding competitors were ten or younger. There seems to be a growing gap between children put on an athletic track (especially in hyper-outdoor towns like Boulder or Ketchum) and those who stay on the couch.

This has the outdoor industry worried. “We discussed Jordan’s age at length before awarding him the Polartec Challenge,” says Nate Simmons, global marketing director for Polartec. “Did we really want to encourage him to pursue this dream at that age?” But then, Simmons says, “we saw that he’s a smart kid, surrounded by a good, responsible team of parents.”

Polartec’s choice wasn’t without savvy. Outdoor-industry customers are aging, and companies fret about the next generation. “This is a recurring theme,” Simmons says. “How do we pull more youth into human-powered outdoor activity?”

That has left Jordan in a bit of a bind. We can lament the fact that achievement too often takes the place of play among today’s outdoorsy kids. But if Jordan wants to inspire others to get outside, he’s got to play the media game blogging and tweeting, sitting for photo shoots and interviews. If he’s going to grab eyeballs away from Wii and World of Warcraft, he’s got to offer something spectacular. Like, say, climbing Everest.

And so, ad alta. The night after his talk to the kids of Big Bear, Jordan is addressing the adults: the town’s Rotary Club chapter.

“I spoke there last year, right?” he says. “So I’ll talk a lot more about the Carstensz climb, which they haven’t heard about.”

Karen nods. She adds a few more photos from Carstensz to Jordan’s PowerPoint show.

When it comes time for Jordan to speak, he steps up to the mike and looks out across the banquet hall. “My name is Jordan Romero,” he begins. “I’m an eighth grader at Big Bear Middle School…” But then disaster strikes. The slide show crashes. The A/V system pipes in a blast of FM rock like something out of This Is Spinal Tap.

And here’s the amazing thing. Jordan doesn’t act like a 13-year-old. Or at least how we might expect one to act. He coolly continues, glancing over as Karen furiously tries to reboot. He talks about Denali, he talks about Aconcagua and Elbrus and Carstensz. When Karen mimes distress, Jordan calmly covers the mike with his hand and reassures her.

“It’s OK,” he says. “I can just talk.”

He speaks about Everest and his campaign to get his peers out hiking. “It gives me an opportunity to teach kids about goal settings,” Jordan says. “You start with a main goal, the summit. And you gotta break it down into smaller steps. You complete those steps and pretty soon you find yourself on top.”

That’s the thing about Team Romero. They’re admirable in so many ways. Paul and Karen, and Jordan’s mother, Leigh Anne, are raising a son who’s vibrantly engaged with the world, and not just for record-seeking glory. Four years ago, Team Romero spent their vacation in Chennai, India, rebuilding a village devastated by the 2004 tsunami. When the recent earthquake struck Haiti, Paul and Jordan immediately began brainstorming about how they could help. These are adults parenting without fear.

Four years ago, Jordan’s passion was herpetology. “He wanted to be the next Steve Irwin,” Karen says. “We had so many snakes in the house, it was like a zoo.” Then his attention turned to mountains. Out went the snakes, in came the hypoxic tent.

“And you know what?” Paul says. “If Jordan comes home tomorrow and says he’s done with mountain climbing and he wants to play basketball, we’ll shut this whole project down and hit the gym.”

Jordan Romero may just make it up Everest. He’s smart, strong, confident, and mature, and the way he handled himself in front of the Rotary Club proves he can stay cool when trouble strikes. But a PowerPoint malfunction is a long way from oxygen-tank failure in a storm at 29,000 feet.

That’s what makes this a tough call. Jordan Romero is an amazing, inspiring kid. He’s everything you’d want in a rope partner, except one thing.

He’s 13.