There is at least one good reason to go climbing in South Africa, and that’s the stone. The geologic forces that turn coal into diamonds have morphed primeval sands into glassy red quartzite reefs that erupt across the country, offering hundreds of world-class climbing areas—from the remote cliffs of Blouberg and bouldering routes in the Cederberg Mountains north of Cape Town to a massive upsurge that looms over the city itself.

climbing south africa

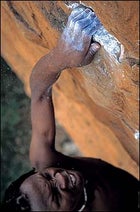

The new generation. 25-year-old climbing instructor Thulani Mazibuko on the cliffs at Waterval Boven

The new generation. 25-year-old climbing instructor Thulani Mazibuko on the cliffs at Waterval Bovenclimbing south africa

Rock country: the author, in the foreground, and Ed February rope up on Touch and Go, a route on Cape Town’s Table Mountain

Rock country: the author, in the foreground, and Ed February rope up on Touch and Go, a route on Cape Town’s Table Mountainclimbing south africa

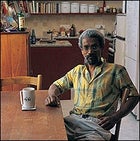

Ed February at his home in Cape Town

Ed February at his home in Cape Townclimbing south africa

Ande de Klerk in Lost World Canyon

Ande de Klerk in Lost World Canyonclimbing south africa

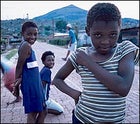

This is Africa: local girls in the township of Waterval Boven

This is Africa: local girls in the township of Waterval Bovenclimbing south africa

Between worlds: rock jock Thulani Mazibuko left the Waterval Boven township for a teaching job with Afrikaner climbing instructor Gustav van Rensburg

Between worlds: rock jock Thulani Mazibuko left the Waterval Boven township for a teaching job with Afrikaner climbing instructor Gustav van Rensburgclimbing south africa

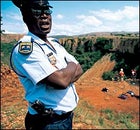

Peacekeeper: an armed policeman on the cliffs at Waterval Boven

Peacekeeper: an armed policeman on the cliffs at Waterval Bovenclimbing south africa

Tangerine dream: Gustav van Rensburg climbing at Waterval Boven

Tangerine dream: Gustav van Rensburg climbing at Waterval BovenJust north of the Cape of Good Hope, a stiff southeaster rips over the summit of Table Mountain, blowing tendrils of fog toward Cape Town’s sunbather-dotted beaches, 3,000 feet below. I’m halfway up a 5.10 route called Triple Indirect, perched on a ledge in the lee of the wind, as my friend Ed February leads the last pitch. Ed is a local and, as one of the country’s most famous climbers, a regular on this crag. Even at 48, his physique is as honed as a featherweight boxer’s. When he shouts that he’s off belay, I clamp my fingers over edges of white stone as solid as kiln-hardened porcelain. The exposure below my toeholds is dizzying. I can see Table Bay, where Dutch ships anchored in 1652 to found Cape Town. Six miles out to sea lies Robben Island, the prison compound where Nelson Mandela was jailed for 27 years. White suburbs hug the coastline, while the black townships of Guguletu and Khayelitsha are a fringe of smoke over the flats.

I pull up and find Ed near the cable-car station at the summit. Though he’s climbed this cliff—a 400-foot quartzite sheet—a score of times, he beams as we coil our ropes. Table Mountain is where South African climbing began, and Ed points along its fortresslike ridge to a distant headwall. “First climbed in 1895,” he says. I try to picture the Victorians who scaled this monolith with hemp ropes back when the motto was “The leader never falls.” And then I try to imagine how Ed could identify with them.

Only a decade ago, Ed wasn’t allowed on many routes in his home country. Under apartheid—the system of racial separation codified by the white Afrikaner minority in 1948—even the outdoors was segregated. And Edmund C. February, doctor of botany, university lecturer, and recipient of the Gold Badge, the highest honor of the elite Mountain Club of South Africa, is black.

UNTIL 1994, WHEN APARTHEID was dismantled, the politically correct way to respond to an invitation to climb in South Africa was to politely decline. Throughout the years of the struggle—from the first state of emergency, in 1960, to Mandela’s release, in 1990, and election as president, in 1994—South Africa was coming apart at the seams. The whole world could see it on the nightly news: an endless video loop of burning townships, white cops in riot gear shooting tear gas and bullets, black protesters returning fire with stones and the occasional AK-47.

Paradoxically, the violence masked a vibrant period of discovery in the South African backcountry. Denied permits to climb in Nepal, Pakistan, India, and most anywhere else because of their government’s racist policies, rock hounds explored their own backyard, extracting first ascents from its unexplored cliffs. Climbers filled the guidebooks with new routes, creating a tightly knit fraternity as fond of beer and practical jokes as any clan of crag rats, except that they happened to be pushing the levels of difficulty into the ether of 5.13. Most were white: There were Dave Cheesemond and Greg Lacey, Cape Town pioneers who both died in mountaineering accidents—in the Yukon and Chamonix, respectively—in the eighties. Martin “Tinie” Versfeld, now 45, the son of famed Afrikaner philosopher and poet Martinus Versfeld, and a climber with a hawk’s eye for new routes. And finally Andy de Klerk, 37, for two decades the country’s top climber, thanks to stiff 5.13 ascents at home and solo climbs of the Alps’ north faces. In 2000, after hearing about these guys for years, I decided to see what I’d been missing.

Here’s what I found on that first trip: Yosemite may rule for big walls, Pakistan for vertical faces, and Thailand for beach cliffs, but South African climbing is singular. It has something to do with the tangerine stone, the big-sky sunsets, the way the rock has settled into a dawn-of-time landscape. By the end of my stay, I’d sampled the best climbing on earth—in one of its most troubling settings. My hosts lived in walled compounds surrounded by razor wire. Carjackings and rape were at anarchic levels in the cities, and in the countryside, attacks on Afrikaner farms were escalating.

There were still two South Africas, it seemed, and I wanted to understand the divide. So when I went back last November with a rope, a rack, and a rental car, my first call was to Ed.

I GOT MY FIRST GLIMPSE of Ed February in 1991. He was clinging to an overhang on Cape Town’s Muizenberg Peak, on the cover of the British climbing magazine Mountain. Already the world’s best-known black climber, he was famed for his bold traditional routes on cliffs near Cape Town and an ungodly number of first ascents with his protĂ©gĂ©, Andy de Klerk. He sported a tight Afro, like a muscular Jimi Hendrix. When I finally met him in the flesh, on a vulture-infested rock tower in Cameroon in 1998, his hair and beard were flecked with gray, as befits a professor.

Ed is voluble, softhearted, irascible, loyal to friends, and drinkative when it comes to single-malts. He’s also the most optimistic South African I know, with little patience for those who’ve given up on the country’s teething problems. He prefers to point to the rural villages getting electricity and piped water for the first time, courtesy of President Thabo Mbeki’s black-led African National Congress government. At the Mountain Club of South Africa (MCSA), he has been the “intergenerational go-between,” as Andy puts it. The bar in the Cape Town club room was Ed’s brainchild, as were the monthly Tuesday-night socials. Yet until recently, his fellow members, nearly all of them white, had no inkling of the depth of the anger inside their friend.

To understand where Ed February’s head is, you have to know that for most of his life, climbing has been a series of humiliations. Take the time in the Cederberg Mountains, in 1978, when Ed and Dave Cheesemond were denied a hiking permit. The ranger told them they couldn’t hike separately—there had to be two people in a party—or together, because mixed-race hiking was also not allowed. Or again in the Cederbergs, in 1983, when Tinie Versfeld fell and cracked his head. Standing at the whites-only entrance at the Clanwilliam Hospital, trying to help his Afrikaner friend stay upright, Ed was ordered to take Tinie to the black entrance. There, another white nurse refused them entry. Like a scene out of Kafka, the two men bounced back and forth for painful minutes until Ed pleaded that the patient just needed a few stitches.

“The system couldn’t conceive that two guys of different color could be hanging around together,” he remembers. “They didn’t know how to handle it.”

Under apartheid, which means “apartness” in Afrikaans, almost all interactions between races were prohibited. Laws classified people as “white,” “black,” or “colored”—for the many South Africans descended from Malays, Indians, and other Asian slaves and Ă©migrĂ©s. “Nonwhites,” the term still used for anyone who is not Caucasian, were forcibly relocated, their homes sometimes bulldozed to prevent their return. Blacks couldn’t vote; the Immorality Act banned interracial marriage.

Ed was born after the clampdown, in the northern Cape Town suburb of Wynberg, in 1955. He describes himself as “black,” though the apartheid government deemed him “colored.” He knows little of his family history, save that his grandmother was Javanese and that February is a slave name, the month of some ancestor’s emancipation. Nevertheless, his skin color meant he was in for hard times. Eighty percent of the country was effectively off-limits, including national parks and game reserves. But each summer, Ed’s father, Ronald February, a schoolteacher, and his mother, Helen, who worked at the University of Cape Town library, circumvented the ban by piling Ed and his two brothers into their Hillman sedan and driving over the borders to camp in Lesotho, Swaziland, and Mozambique. “They had the same viewpoints as everyone else,” Ed says. “The love of nature, the love of wildlife—primarily because that’s what middle-class South African people are into.”

Drumbeats of the struggle punctuated Ed’s youth: the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, in which white police shot and killed 69 black protesters; Mandela’s imprisonment for high treason, in 1962; the bloody Soweto student riots of 1976. In college, Ed vented his rage at sit-ins that often ended with the police pulling out their quirts—or whips. “The first couple of protests, you get caught and beaten up,” he says. “Then you learn to run away.”

In 1977, Ed led a class walkout at the University of the Western Cape, a school for nonwhites, over a white history teacher’s revisionist lesson, in which Afrikaners were the chosen people. “I turned to the class and said, ‘This is bullshit; you shouldn’t be condoning it,’ ” he recalls. Only a few students followed him out. For outbursts like these, Ed’s teachers eventually flunked him, so he hauled up to Johannesburg and trained as an industrial radiographer, testing welds in an oil refinery.

“I think I’m probably more bitter about it now than I was then,” he says of apartheid. “Then, it was the system, it was how things were. They had everything; I had nothing. It’s how it was. You didn’t go around feeling anything about it; you just dealt with it.”

Ed’s way of dealing was to turn to the mountains. “It was a pretty sick society,” he says. “Climbing was normal.”

GROWING UP IN THE SHADOW of Table Mountain, Ed started climbing early. At 14, he was pedaling his bike to nearby Elsies and Muizenberg peaks, on the Cape Peninsula. There were a number of black climbers then, men who’d grown up before apartheid marginalized Cape Town’s black middle class, including Charlie Hankey, a distant uncle of Ed’s, and George Ganget, both of whom put new routes up Table Mountain in the fifties. At 16, Ed joined the Cape Province Mountain Club, a climbing club for nonwhites that had been around since the thirties. Ganget and other members took his skills to 5.8 and 5.9 levels, but within a couple of years he was outclimbing his mentors.

At Table Mountain, Ed would run into top climbers from the all-white MCSA and make small talk, but no one would tie in with him. At first Ed dragged his little brother, Rodney, out to hold the rope. But slowly, he and two other young black climbers, Ed January and Maurice Wyngard, found colorblind white partners. Dave Cheesemond broke the ice, in 1974. Then came Greg Lacey, Tinie Versfeld, and a high school kid named Andy.

When Ed and Andy de Klerk met, in 1981, they were an unlikely match: Ed was 26, Andy 14. Andy already had a bit of buzz as a kid with potential, so Greg and Ed invited him to go climbing on Table Mountain. “It was clear he was awesome,” says Ed. “He was climbing quantum leaps ahead of his day.”

Their partnership was one most climbers would envy. “Ed took me under his wing,” says Andy, who today looks more surfer than climber, with unkempt blond hair and a ubiquitous cigarette. “Race was never an issue.” Ed would pick Andy up at his house—with his mother’s blessing, which Ed still finds remarkable—and they’d hit the rocks, picking areas where they wouldn’t get any racial flak. They stopped counting new routes around 500.

To this day, repeating a de Klerk climb is a serious undertaking. One sweltering day early in my trip, Ed, Andy, and Tinie take me to the 120-foot pitch Technicolor Darkness, in Lost World Canyon, 100 miles east of Cape Town, near the town of Montagu. With a rating of 5.12b, it isn’t hard by modern standards, but it’s local custom to add a couple of grades to any de Klerk route. When I’m handed the rack to lead, I know I’m in for a sandbagging.

The rock is as smooth as a windowpane and split by a single hairline fracture. I climb halfway up before my forearms fail, and I plummet 20 feet. It’s the first of many falls. When I finish the route, I’m thrashed—yet pleased with my inelegant ascent.

“Did I mention that this mad bugger soloed that thing when he was a schoolkid?” Ed says. He and Andy were camping at the route’s base. Ed slept in, but 17-year-old Andy got up early and scaled the face without a rope. “Solo climbing is the ultimate in mind control,” Andy’d said when Ed took him to task.

The two continued to break new ground through Andy’s years at the University of Cape Town. But in 1989, as he was about to be drafted to fight in South Africa’s border war with Angola, Andy lit out for Europe, then the United States. He landed in Seattle, married an American climber named Julie Brugger, and didn’t return until 1998, after their divorce. He now lives in the seaside town of Scarbrough, 30 miles south of Cape Town, where he makes custom furniture. He’s remarried, to a general-practice physician named Charlotte Noble; they have a two-year-old son, Sebastian, and another child on the way.

“Avoiding an unjustifiable war was part of why I left,” Andy tells me. “But I also didn’t want to lose two years of climbing.”

BUCKING THE SYSTEM—whether apartheid or the draft—was just one more ability that Ed and Andy shared. But it didn’t make living in South Africa any easier.

In 1981, Ed met Nicky Allsopp, a graduate student in botany who now works for the government’s Agricultural Research Council, helping communities rehabilitate rangeland. Because Nicky is white, “it was against the law for us to be going out together,” Ed says. “We couldn’t go to movies, restaurants, pubs, or the beach together, but we could go hiking.” In 1984, they moved to the predominantly Muslim neighborhood of Bokaap, into the house where Ed’s father was born and where they still live. In Bokaap, people weren’t bothered by an interracial couple, and in 1996, they wed.

Ed threw himself back into academia, finishing a doctorate in botany at the University of Cape Town that same year. Still, as a climber, he felt like he’d been left behind. For years, he’d watched white friends set out on club-funded expeditions wherever their passports were welcome—mainly in the Andes. “I am pretty bitter about it now,” he says. “I can sit and listen to these guys talk about all the great expeditions all over the world they went on, and I think, Fuck, those were the days I was struggling to find a climbing partner. And I was probably climbing twice as hard as any of them at the time.”

In 1996, Andre Schoon, then president of the MCSA and still an active member at 65, knocked on the Februarys’ door. Ed was 42 by then, a grand figure in South African climbing, and Schoon wanted him to join. Ed was reluctant—he’d criticized the club in the press as a white-elitist institution even when, in 1986, his friend Richard Hess, a black entrepreneur from Cape Town, joined as the first nonwhite member since the club’s founding in 1891. (Hess no longer climbs.) But now Mandela was calling for racial unity despite having been locked up for half his life. “I joined,” Ed says, “primarily because I agree with Mandela—we all have to work together to form a united South Africa.”

Ed would be one of the few nonwhites in the 1,800-member Cape Town section, the largest of the 4,500-member club’s 13 chapters. (The club has 35 nonwhite members today, 20 of them in Cape Town.) “I received a lot of criticism from people in the nonwhite climbing clubs,” he says. In 1998, Andy Johnson, the father of black climber Trevor Johnson, went so far as to call him the MCSA’s “rent-a-black” in the Cape Times newspaper.

In 2002, the club gave Ed the Gold Badge, the first time they’d awarded it to a nonwhite. Though gratified to receive it, Ed was still adamant that the MCSA owed him, and the entire nonwhite outdoor community, a formal apology. The nation had just undergone a wrenching national catharsis—the process of historical reckoning that emerged from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, in which apartheid’s worst oppressors had asked for forgiveness. Ed felt the club should, too.

“If the foremost people in this country have apologized, then what is it for the mountain club to say they’re sorry?” Ed asks. “They want to sweep this matter under the rug. That’s where my bitterness stems from.”

THE GEM OF SOUTH AFRICAN CLIMBING is the Milner Amphitheatre, east of Cape Town in the Hex River mountains. A double-tiered cliff the size of El Capitan, the face boasts a host of 5.11 and 5.12 free climbs that parallel a 2,000-foot waterfall plunging over flint-hard quartzite the color of a Florida orange.

I’m with Tinie, Andy, and Tony Dick, a fifty-something Cape Towner who still climbs 5.11. To the dismay of the other two, Andy’s brought along his parachute and a Birdman wing suit. His friends always worry when Andy brings along his BASE-jumping rig, especially at 2,900-foot Milner. He’s broken his knee on the landing here—twice.

We’re a noisy bunch, cackling and joking on the three-hour hike to the cliff. Andy has hidden a 15-pound rock in my backpack, which I carry uphill for two hours before discovering it. As I fish it out, Tony, who is something of a raconteur, tells a story.

It’s Angola, circa 1975, and his platoon is taking a break during patrol. They’ve lit a braai, or barbecue, and they’re brewing tea and frying boerewors, spicy Afrikaner sausage. Next second, teapots and sausages explode into the air, and the rat-a-tat of small-arms fire sends everyone diving for cover.

“We’d made our bloody fire over an ammo cache that some rebel lads had buried,” he quips.

That war comes up a lot among middle-aged climbers. It’s a generational tag: Young South Africans who are cranking hard routes talk about cranking hard routes; climbers over 35 talk about politics, apartheid, and Angola. Forged discharge papers, wildebeests stampeding patrols—these tales are told casually around campfires and on drives across the veldt.

After a long day on the rock, Andy scrambles to Milner’s highest point. He pulls out a cigarette, then calls his mother on his cell phone to wish her a happy 68th birthday.

“Where are you?” she asks.

“Milner.”

“Are you going to jump?”

“Right now.”

“Then be safe!”

He hangs up, steps off the edge, flies for 25 seconds, and deploys his chute. Tinie and Tony breathe a sigh of relief.

Andy is not alone in his cavalier attitude toward danger; in fact, most South Africans seem to share it. One afternoon, I arrive at his furniture workshop, in an industrial park in Kommetjie, a half-hour drive from the city. I’m fresh from reading newspaper reports of a survey by the national police. South Africa is one of the most murderous societies on earth, one story proclaims: 21,738 murders in 2002, compared with 16,204 murders in the U.S., a country with six times the population. To me, the statistics warrant a minor freak-out.

“Why are you so hung up on doom and gloom?” Andy asks.

I look around the shop. Andy was padlocked behind a steel door when I arrived. Electrified wire and Armed Response security signs ring the building. He locks his tools in a safe every night.

“Looks like you’re in prison to me,” I remark.

“Ah, it’s the Wild West out here,” he says, shrugging it off.

Andy reluctantly accepts crime as a function of township poverty, which has persisted in the post-apartheid years. “My neighbor was burgled last winter,” he tells me. “You know what they took? Food. And warm coats. They left the television.”

He takes a thoughtful drag of his smoke, then says, “You should visit a township.”

THERE’S SOMETHING CREEPY about gawking at poverty from an air-conditioned bus, so I sign on with şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř Without Limits, a township-tour outfit that lets you gawk from a bicycle. For $46, I get transport to the Cape Peninsula’s Masiphumelele township, a rattly bike, and the guiding expertise of a 23-year-old Xhosa woman named Noluthandu.

We pedal down potholed roads past shacks that are more like collages of tin, brick, wood, plastic, and cardboard. Families share communal taps and toilets. Residents run jury-rigged wires along the ground to poach electricity from power lines. A woman sweeping her stoop waves us over. She’s watching Days of Our Lives.

Noluthandu shows me a spaza shop, a penny arcade where a single cigarette or a slice of bread can be bought. Then we stop at a shebeen, or bush pub, but one of the men inside yells something rude in Xhosa. “Let’s go,” she says. It’s afternoon, and the boys are well lubricated.

Masiphumelele sprouted up in the early eighties as an unnamed squatter camp for unemployed Africans and those working for whites in Cape Town. Concerned with slum conditions and rising crime, whites petitioned to relocate the squatters. Police ran them off, but after the laws preventing blacks from moving freely were abolished, in 1986, people slowly returned and built an “informal settlement” whose population has grown to 26,000. In the end, Masiphumelele—Xhosa for “We Will Succeed”—prevailed.

şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř the township are shacks built on a swamp—a case of squatters squatting on squatters—and we push our bikes to a small hutch. Inside are three sangomas, or healers, all women. A drum starts up and the broad-hipped matriarch leads the trio in a foot-stomping dance. At the end, they stand before us, panting.

“Ask them questions. They are fortune-tellers,” my guide says.

“Do you have a question?” I ask her.

“Me? No, I don’t believe in this. I am a Christian.”

We ask the matriarch what she sees in Masiphumelele’s future.

“This township is doomed. AIDS will destroy the people. We have nothing. The men have no work. There is no medicine.”

I pedal away, wondering how to digest a tour in which misfortune is the main attraction. On the way out, an eight-year-old boy hops on the back of my bike and cadges a ride. When it comes time to jump off, he high-fives me and smiles. Like any kid anyplace.

IN A COUNTRY BLESSED with rock, it seemed odd that I met so few black kids climbing. Though soccer, cricket, and rugby are hugely popular among black South Africans, there are few incentives to get township youth on a rope. As in America, climbing is still a white middle-class hobby. Ed blames apartheid for killing the love of the outdoors in black culture—that and the fact that a pair of rock shoes costs more than some people earn in a month. But in an unlikely place, I meet an exception.

East of Johannesburg is Waterval Boven, South Africa’s premier sport-climbing area, where the rust-red cliffs along the Elands River draw an international crowd. With 13 churches, three pubs, and 12,000 people, Boven is two towns—one white, one black. No barrier divides them, but the transition between gardened avenues and ramshackle Swazi township is stark. I rent a room at the Roc ‘n Rope hostel, which the owner, a 30-year-old Afrikaner named Gustav van Rensburg, and his French wife, Alex, 33, run as a climbing school. When we head to Boven’s crashing waterfall the next day, Gustav brings a police guard.

Crime became an issue for South African climbers three years ago, after a spate of holdups at the Wave Cave, a popular crag in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. Boven is 500 miles from Natal, but Gustav was worried about photographer Jimmy Chin’s cameras. Recently, a township tough wielding a machete had threatened to cut a rappelling climber’s rope unless he handed over money. The climber slid down; the would-be thief ran off.

Several days later, on a climb called Rude Bushman, my partner is a dreadlocked 25-year-old Swazi named Thulani Mazibuko. Thulani’s name means “silence,” but once we start climbing, he opens up. He tells me he was just another township kid looking at a bleak future until he took a climbing class from Gustav. Seeing his talent—he’s climbed 5.12—Gustav gave him a teaching job. Thulani now rents a room at Gustav and Alex’s place.

Thulani moves easily between the township and the van Rensburgs’ house, aloof but not above the loiterers outside the Like Father Like Son liquor store. His ambitions are straightforward: move from Boven someday, go to school, find higher-paying work. But he’s in no hurry to leave.

“Township guys think it’s strange that I live with white people; they call me a white man,” he says. “But I don’t care.”

FROM BOVEN, I DRIVE east to Kruger National Park, then south through the lush foothills of the Drakensberg Mountains and back to Cape Town. I arrive in time to attend a slide show at the MCSA’s Tuesday-night social. There’s a friendly buzz in the air, and the bar is doing a brisk trade in Windhoek Lager. Ed works the crowd, dispensing hugs, shouting high-decibel greetings.

When the crowd is called to take their seats, Tinie strides to the front, holding a single sheet of paper.

“I feel we need to address issues from the past,” he begins.

A hush falls over the room. Calling the club’s history “a disgrace,” Tinie condemns it for having embraced apartheid in exchange for government grants and access to land. “We must apologize to all those who have been hurt,” he concludes. Everyone seems glad for the lights to fade.

şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř on the street, the talk is lively.

“Well done, my man,” Andy tells Tinie. But others disagree.

“Why should I apologize?” one twenty-something white climber demands. “I was a kid during apartheid.”

Though Ed appears to be the only nonwhite climber present, few address him on the subject. It’s too awkward. After the crowd drifts off, Ed and I go back to his place with a 27-year-old white climber named Tristan Furman. Tristan is sympathetic to Ed’s position, but, like other young climbers, he seems to feel that the need for an organizational apology has passed in the new South Africa. Around 1 a.m., after a few drinks, the discussion heats up.

“Ed, how many nonwhites have you introduced to climbing?” Tristan asks.

“That isn’t my responsibility,” Ed answers, irritated, adding that he’s done enough to inspire others by being the country’s preeminent nonwhite climber.

Tristan then describes how his family’s farming community was attacked by black hoodlums, with murderous results. “No one has apologized for that,” he says.

“We don’t have to,” Ed tells him. “We won.”

Moments later, the tension ebbs. “Well, we’ve all suffered in this,” Ed says calmly. “We should all apologize.”

That seems to be the nub of the argument: Who are “we” in South Africa? With so many cultures—more than a dozen black ethnic groups, Afrikaners, British-bred whites, Indians, Asians, and those containing a bit of everybody—perhaps there are too many South Africas, each a separate island waiting to be bridged.

Ed and Tristan part as friends, but a few months later, back home in Utah, I get an e-mail from Ed. It’s an open letter to Greg Moseley, the 63-year-old Cape Town MCSA chairman, sent to climbers across South Africa. The letter is long and, at times, seething with anger. Ed enumerates a list of grievances—from the club’s failure to apologize to its tardiness in recruiting a more diverse membership—before concluding, “As a nonwhite South African, I can no longer compromise my integrity by being an active member of this organization.”

I phone Moseley. He’s responded to Ed’s letter with one of his own, he says. Tinie’s remarks led to the formation of a working group that included, among others, Tinie, Tristan, Andre Schoon, and Jonathan Levy, a Jewish climber. A “draft apology that would also include the Jewish community” is being formulated; Ed just isn’t aware of it yet. Moseley is optimistic that the club and Ed are “now on the same wavelength.”

Ed sounds less hopeful when we talk: “They’ve been putting the apology off for years. Why not just do it?”

Most of those close to Ed support him. “Ed had to stir the club out of its comfort zone,” says his wife, Nicky. “Whites think they’ve moved on from apartheid, but blacks are still angry.”

“It’s been a long time coming, and Ed has no regrets, but I think the MCSA will come around,” Andy says. “Don’t be surprised if Ed is president of the club someday. Look at Mandela: He went from prison to president.”

STRANGE, THE MENTAL snapshots South Africa leaves with you. A donkey cart overtaken by a BMW. A Boer farmer spraying spittle and beer in a Karoo pub, shouting, “We used to live like kings! Now we live like princes!” The cloud-capped Drakensberg Mountains rising above the tin roofs of a township. And in the middle of it all, Ed February, a man standing at the center of the new South Africa, balanced between two worlds. Time will tell whether Ed returns to the MCSA. In the meantime, the rock remains unchanged.

My last climb is with one of Ed’s oldest friends, an orthopedic surgeon named Charles Edelstein—or Snort, as friends call him, because of his sinus problem. Snort has known Ed since 1978, when he was a dirt-poor med student renting a flat in Jo’burg. He took Ed in, which doesn’t sound like a big deal, except Snort is white, and it was illegal. We drive to Blouberg Massif, a 1,200-foot quartzite mesa near the borders with Botswana and Zimbabwe.

As we get closer to the mesa, the vegetation disappears, picked bare by goats and bony cattle. At the village of Blouberg, a Tswana boy leads us to a kraal, a village compound, and into a parking spot seemingly reserved for us. A woman leans in the doorway of a mud hut, a cell phone dangling incongruously from her waist.

“You are Charles,” she says languidly.

Snort has been climbing here for 25 years. He pays her to baby-sit the car, then, with the sun sinking, we saddle our packs and head uphill, hiking in the relative cool of the evening until, around midnight, we make camp in a cave.

At dawn, the rock is already griddle warm. Whenever I poke a cam into a crack, lizards scrabble up the wall. We climb all day, the hot air silent but for the jangle of cowbells.

The sun is sinking, throwing long shadows across the savannah, when Snort finally pulls himself over the top. I hear him shout, and I look up. He’s standing on the cliff edge, yelling, arms raised and fists clenched:

“This is Africa!”