In December, I wrote about Alex Honnold for the cover of ���ϳԹ���, ahead of his planned ropeless climb of Taiwan’s 1,667-foot Taipei 101 tower, now the world’s fifth tallest building. Sender Films had recently sold the project to the National Geographic Channel as a live television special. It was going to be the biggest thing yet for the 28-year-old nomadic climber, who’d already been featured on for his life-or-death free-solo climbs in Yosemite. It would also arguably be the most significant media events in rock-climbing history.

Then the whole thing kinda fell apart. The building climb was postponed indefinitely after the adults at National Geographic began to worry about things like safety and liability. There had been talk of putting mattress-like crash pads on the balconies among the thousand other details that needed to be sorted out if this was to be as big as Discovery’s Nik Wallenda live high-wire acts or Red Bull’s Stratos stunt.

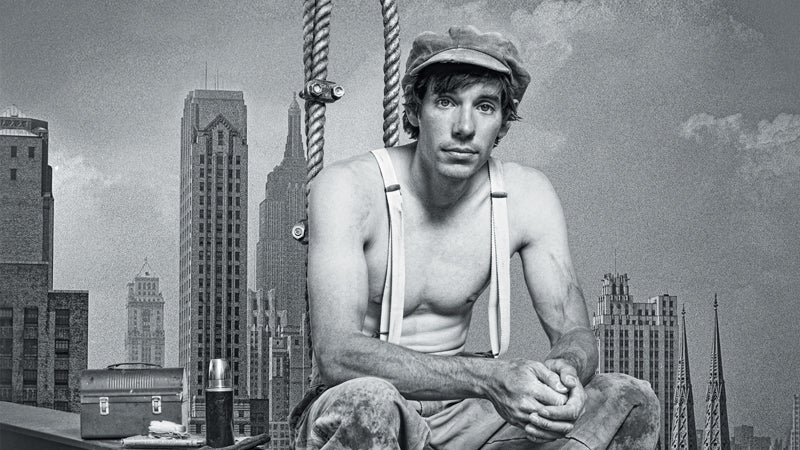

Lost in all of the hype—and one really awkward photo—was the fact that Honnold remains a remarkable climber who’s doing more than anyone to push the boundaries of his sport. For those of you interested in following his career, the time to get excited isn’t when the dog-and-pony show—as professional climbers call it—is in full effect, but when Honhold disappears. This is how he’s done most of his amazing free-solo climbs in Zion and Yosemite national parks. So it went on January 15, when Honnold made the first free-solo ascent of Mexico’s 1,500-foot 5.12+ Sendero Luminoso. With him was a minimal crew of friends and cameramen. The climb was among the most difficult and committing routes that anybody has ever dared to climb without a rope. It also provided the material for a very successful North Face viral video.

Honnold’s next feat—the Fitz Roy Traverse, in Patagonia, with Tommy Caldwell—had almost no commercial application (or advertisement). That climb took five days, between February 12 and 16, and was ������ Alpinist magazine. (The late Chad Kellogg was on Fitz Roy at the same time.) It was just one of those pure climbing feats that reminds everyone what a guy like Alex is really about: Knocking off some of the most difficult routes on earth, in the most outrageous style, and making enough money doing it to avoid washing dishes or guiding clients.