“SO THIS IS THE LEGEND,” Todd says, after we’ve finally chased it down. He sets another stick on our tiny campfire, slouches onto the tangle of climbing ropes, and begins rubbing the dried blood from his knuckles…

Out of the swirling dust devils of antiquity, the legend had gripped our imaginations and possessed us. Once upon a time, Fred Beckey, the ur-dirtbag of climbers, lit out for Mexico. He dragged his partners from their beds and gunned across the moonlit desert in a low-slung station wagon. Infamous Fred Beckey, an eat-from-the-can vagabond, had put up more first ascents than any man in America, so perhaps he was simply widening his search for more ���DzԳٲ�ñ����.

It is unclear how long Fred and his friends were down there, banging along mule-cart tracks between the cacti, living on tortillas and frijoles, roaming a labyrin- thine dreamscape streaked with sunlight.

Eventually, the gringos stumbled upon a gleaming mountain of white granite that rose up out of the desert. The stone was as clean as Yosemite, but with the rugosity of the rock at Joshua Tree. Beckey and his compadres purportedly climbed a chimney system on the southwest face. Then found their way back across the border, elated, exhausted, and sworn to secrecy…

And now, two decades later, Todd and I have rediscovered this El Dorado of rock in the hidden corazón of Mexico, and we’ve climbed its apocryphal face. We’re curled up close to the fire. We have no sleeping bags. We’re out of water, out of food. Our eyes are so bloodshot they’ve hemorrhaged. But we have followed the legend and now we’re here, lucky to be alive.

I HAD TRIED HUNTING down the peripatetic Beckey, now in his late seventies and still living the road-tripping climbing bum’s life. He supposedly lives in Seattle, but good luck finding him there. All I ever got was a letter from a friend of his named Lisa, who wrote to say she was leery of the legend: “I would say it was one of FB’s stories. He takes great delight in starting rumors.”

One day Todd Skinner, who had refused to give up the chase, phoned.

“Saddle up.”

“Where we going?”

“Mexico.”

He’d tracked down an ex-smoke jumper named Mark Motes, who claimed to have been on Beckey’s fabled South of the Border sojourn in 1980.

“Motes says the peak is somewhere west of Durango near a pueblo called Peñon Blanco. It’s all really vague. I’ll bring the ropes and a rack.”

“I’ll get maps.”

One week later we’re switchbacking up into the Sierra Madre Occidental west of Durango in a rented jeep. The road is called El Espinazo del Diablo—the Devil’s Backbone—and it runs along an arêe, with arid, incised canyons thousands of feet deep dropping off to either side. Ominously, all the rock we’re seeing is volcanic, most of it either rotten or overgrown with thornbushes.

For the entire day we have little idea where we are and no idea where we’re going. Then, at twilight, we pass a startling sign that gives us our exact location: TROPICO DE CANCER, LATITUD NORTE 23º7′, LONGITUD OESTE 105º0′.

After dark, we pull over in a village named Los Bancos and spread out our maps. Several old men gather round.

“Donde esta el blanco peñon?” Todd asks, forming a mountain with his hands.

“Sí, sí,” says the oldest man, placing a thick, yellowed thumbnail on a distinct spot: Cerro el Peñon. The closed contours clearly indicate a mountain. Near the peak is a village called Palo Blanco.

“Hah!” Todd is delighted. “I knew it! Maybe the village was called Palo Blanco and the peak itself Peñon.”

But something else doesn’t quite fit. We have already passed this peak and surveyed its walls and all of them have been unquestionably volcanic, not gleaming granite.

We discuss the many possibilities for these inconsistencies while the caballeros look on. Todd reluctantly points out that discrete, clear facts and amorphous old myths rarely jibe. Over time, small tales become tall tales. Words become fungible. Blanco, palo, peñon. Granitic, volcanic.

We go back to the maps. Our key words begin to leap out everywhere. Los Blancos. Cerro Pelon. Cerro Blanco. Llano Blanco. Cerro el Pino.

“Ever go snipe hunting, Todd?”

“Peñon Blanco,” Todd says again, enunciating for all he’s worth.

The old man pipes up. “Peñon Blanco? No, no, señor escalador. No, ese no es el lugar.”

The old man begins scouring the maps, his dark, battered fingers moving from river to mesa to ridge crest.

“Aqui.”

This time his cracked thumbnail has stopped in the far corner of a map we only brought by chance. “That’s over 150 miles in the opposite direction from the area we were told to search,” Todd says incredulously.

“Exactly,” I reply.

WE LIE SCRUNCHED against the fading fire, staring up at silver bands of Mexican stars, too cold to sleep, too tired to keep talking. It’s past midnight. I hear Todd’s breathing slow. I’m still awake, trying to puzzle him together.

Todd Skinner, 43, raised in Pinedale, Wyoming. Summited Gannett Peak, the highest in the state at 13,804 feet, when he was 11. Elk-hunting and horsepacking guide for almost two decades, farrier when the horses needed shoeing. Connoisseur of antique saddles and renowned collector of vintage Old West guns. Directed and produced eight climbing films, from Vietnam to Pakistan; husband of Amy; father of Hannah, 3, and one-year-old twins, Jake and Sarah. Owner of Wild Iris, a Lander, Wyoming, outdoor shop.

And—oh, yeah—the most controversial rock climber in America.

Todd went to the University of Wyoming on an alpine-skiing scholarship in 1977 and left five years later with a degree in finance and a reputation as the most contentious climber since the late Warren Harding.

It all started at Vedauwoo, a granite outcrop near Laramie famous for its flesh-ripping off-width cracks, where both Todd and I apprenticed. Vedauwoo disciples like me adhered to a strict set of commandments passed down from the early days of mountaineering.

Never fall. If you do, lower off immediately; you shouldn’t have been on the climb in the first place. Don’t lead what you can’t lead. All climbs are done ground up, no previewing. All bolts are put in on lead. Hanging on gear is a sin worse than coveting thy partner’s girlfriend. All climbs must be done in stoic, heroic style—no hangs, no tension.

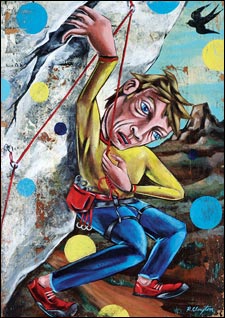

Then Todd Skinner showed up in the summer of ’78. With heretical disregard for the old rules, he and partner Paul Piana began putting up routes so difficult it was impossible to do them without practicing. Bolts were placed on rappel and the climbs “worked” via “hangdogging.” You fell all the time, relying on the bolts and other protection (“pro”) until you mastered the move. Attempting climbs that were over your head was the point.

As his reputation grew, Todd was excoriated, his ethics decried, his style lampooned. He was the bête noire for every mountaineering traditionalist from Boulder to Banff. As other climbers embraced safe, well-spaced bolts, mortal boldness diminished, but ratings and skill levels leapt by two full grades. Rock gymnastics had come to stay.

Today, nearly 25 years later, many of Todd’s early offenses are standard operating procedure in several climbing disciplines. All sport climbs are rap-bolted, to say nothing of the artificial world of gym climbing. World-class sport climbers may practice the same move, just like a gymnast or a figure skater, for years before perfecting it.

Todd Skinner was a radical nonconformist, but in some ways he was just ahead of his time.

THE DAY BEFORE THE CLIMB:

I’m driving while Todd hangs out of the jeep, scanning the desert with binoculars.

“Well, I’ll be gawddang!” he yells. “Pull over.”

Off in the distance, poking miraculously above the red haze, is a white pyramid. We find a dirt road beelining for it and go.

An hour later we’re scrutinizing the maps at a fork in the road when two vaqueros appear. They trail their cattle past us, stop, lean on their saddle horns, point when we ask a question, then ride off.

Passing through a one-street adobe village just before sunset, we are stymied by a wide arroyo. A villager strolls up to our jeep. We point to our glowing peak, pink in the evening light.

“Ese es bonito Cerro Blanco,” he says regally. He tells us a better place to cross the arroyo, then passes a clear Pepsi bottle into the cab. We each take a swig. It is the smoothest, smokiest tequila on earth. The man winks and takes a slug himself.

“Buena suerte, amigos.”

“That’s as close as you can come to communion,” Todd says.

By noon the next day we’re there. We’ve forded half a dozen bone-dry streambeds and three streams, passed through numerous barbed-wire gates, parked in a cottonwood ravine, hiked for an hour up through a rock-walled col hirsute with giant yuccas, and now stand at the base, looking up at Beckey’s white mountain.

Most myths are best enjoyed around a campfire and not actually pursued. But some people can’t help themselves. Todd has spent half his life being a myth destroyer—and, consequently, the other half being a mythmaker.

I examine the cone of white granite through binoculars, gradually moving up the south face. It is perhaps 1,000 feet high. Although there are several fissures—I can identify the chimerical Beckey chimney—only one crack cleaves the face bottom to top.

“Todd,” I say fervidly, “the central line will go.”

“I’m going to check out the boulders,” Todd says.

When he returns, he’s carrying a pottery shard, a broken spearhead, and a stone scraper. We spend the rest of the afternoon reconning the area, discovering pictographs underneath three different boulders.

Walking back to the jeep in the dark, Todd says, “It’s the search itself I love, not what I’m searching for.”

WE’VE USED UP all our wood, and the fire is dying out. We’re both awake now, talking.

Todd spent 18 winters in Hueco Tanks, Texas, training. Three summers in a tepee beside Devil’s Tower putting up outrageous routes, two more in a tepee at Mount Rushmore.

“I realized that you had to live with the rock,” Todd says. “That was the only way to fully comprehend and then test the boundaries. After a while I began to see the limits of possibility in different places and started searching. I didn’t have an apartment for seven years. I was looking for rock with a future.

“History means jack. The places with the most history have the least future,” Todd continues. “Most rock-climbing areas are dead ends, due to the nature of the rock. Places to visit, but not places where you can live with the rock. To do that, the quantity and the quality of the rock must combine to allow limitless improvements in difficulty.”

Todd and his partners have put up first ascents, none rated less than 5.12+, on the hardest continuous rock climbs ever attempted. He spent 60 nights on the east face of Trango Tower in Pakistan in 1995, completed a 14-pitch masterpiece up the strongest line on the Hand of Fatima in Mali in 1998, free-climbed the Geneva Dihedral on Ulamertorsuaq in Greenland in 1999, and made it up the east face of Poi in the Ndoto Mountains of northern Kenya in 2000. But they are not alpine climbs. They are well protected. You are not going to die. Todd believes in safety and, unlike almost all mountaineers the world over, does not equate adventure with risk.

“���ϳԹ��� is pushing yourself into unknown realms,” Todd says, “not dying just because the pro sucked.”

TWENTY-FOUR HOURS EARLIER:

We are up at four. By daybreak we’ve battled 500 vertical feet of thornbushes to gain the base of the wall. I get the first lead. Classic 5.9 toe-heel off-width crack, eight inches wide—too big for my hands, too small for my body—with the occasional yucca to climb through to keep things interesting. On the next pitch, Todd leads up through 5.10, legs straddled and stemming, with no pro—hand jams, a fingertip lieback, then a dirt overhang that requires an ungainly belly flop onto an ill-placed cactus.

Pitch three starts in a chimney and shoots out to a giant roof hung with clumps of green moss the size of pineapples. I stem in full splits, tearing away the moss.

“Is there gear?” Todd yells anxiously.

“The rock is rotten!” I hear the fear and weakness in my voice.

Digging desperately with my fingers, I manage to hollow out a space for a camming unit in the wretched rock. There’s an absurdly flaring crack that goes out the left-hand side of the roof. In a full-body stem, both feet on one wall, both hands on the other, I attempt to calmly assess the feasibility of the crack. But soon I start shaking so bad that at the last possible moment I cram a fist jam deep into an exfoliating hole—and fall.

To my surprise, the fist jam holds. Dangling by one arm, I slam in another cam and then promptly fall on it. Unbelievably, the piece holds, although only two of its four lobes have wedged. It could pop at any second. I’m swinging in space.

I’m too scared to lower off this horrifying piece, so I climb. It is the ugliest off-width in Mexico. I use flared fist jams, chicken wings, arm bars, a shoulder wedge, stacked fists, a head jam, every single crack-climbing trick I ever learned in Vedauwoo. There is nothing for my feet. The upper half of my body is plugged up in a hole, and my legs merely flail in midair. I manage to insert one side of my body in the crack. But there’s no pro. None! I’m so far past the point of no return I could vomit. I talk to myself. Calm myself. Consciously stop my legs from shaking. Then, inch upward.

For the next hundred feet of climbing I stab the dirt in the back of the crack and the wind blows it back into my eyes and mouth. Crazed with terror, I somehow wiggle in just two small, bad, no-hope-at-all-of-holding-a-fall pieces before hitting the end of the 175-foot rope.

The crack is too wide to protect. There is no belay, only clods of dirt. I have no choice: I tie into them with a sling. The wind is now howling. My eyes are so packed with dirt I can no longer keep them open. I scream instructions for Todd, 175 feet below, and he screams back at me, but neither of us can make out what the other is saying. I yell myself hoarse trying to make sure he knows he can’t fall, no matter what. The dirt-clod belay would not hold us.

We are trapped midway up our mythical wall. The sun is falling from the sky, the wind screeching. We can’t communicate. We have no alternative but to go on instinct and experience.

With my eyes crusted shut, I feel the ropes. At the slightest change in tension, I delicately pull up rope. Time is of no importance. As long as Todd doesn’t fall and pull us both to our deaths, I could belay for hours, days, weeks. I go into a half-conscious state, concentrating on sending good vibes through my fingers down inside the rope to Todd.

The next time I open my eyes, Todd has climbed through the roof and heaves into view on the face below me. He motions for me to pull up the haul line, which I do. Knotted to the end, I’m everlastingly grateful to find, is a cam that Todd had removed from the crack below. I jam it deep into the crack, and it’s solid enough to anchor a fall. Suddenly I have a real belay.

When Todd climbs up to me he’s as shaken as I am.

“Holy Christ, hombre! That’s harder than any 5.12 I’ve ever done! I would never have led it.”

“You did, Todd. We both did.”

There are two more difficult pitches to the top. It’s dark when we pull over the lip. In a summit cave we gather wood and make a fire and settle in for a long, garrulous bivouac.

THE ASHES ARE COLD and we’re stiff as wood when the sky finally begins to lighten. It will take us half a day to find our way off the mountain. For the first time, we’re actually talking about climbing, the pretext for our adventure in Mexico.

We agree that the middle pitch was absurdly dangerous, deserving of an X, or death fall, rating. We thus dub it the Dos Equis pitch.

And a name for the climb itself? El Vedauwoo.