With little more than a pair of running shoes and a tube of lipstick in my carry-on, I flew home in August 2008 to help my mother empty out my grandmother’s house. Granny, Mom’s mom, had succumbed to a fraught battle with non-smoking-related lung cancer in 2004. In the four years since, Granny’s house on Washington Street—the mint-green stuccoed haven where Mom and I had first taken refuge when we moved west, the same house where I’d spent a year between high school and college caring for Granny during rounds of chemo and experimental drug therapy—had sat untouched. It was a mess. Every corner was filled, every closet jammed. Fifty years of junk and sentimental treasure poured from its seams. Mom and I would make My Brother’s Keeper jokes, giggling darkly at how you could enter the place and never emerge. In truth, though, I knew it mortified her, the thought of being buried under all that emotional baggage. It was time to let go. And so I came home.

For nearly two weeks we rummaged through Washington Street. We began in the boiler room and fanned upward, floor by floor, sifting through tokens of fond memories and sweeter times long since reduced to dusty, decomposing matter. There were garish souvenirs from trips abroad and incomplete collections of crystal stemware, stacks of sheet music and stamp collections, dolls with missing appendages, army medals. By sheer virtue of the fact that seemingly nothing had ever been thrown away, everything was endowed with worth. Mom and I see-sawed between what to keep and what to trash. Ours was a complicated system of hoarding and purging.

One afternoon I decided to attack my grandmother’s attic. My relationship to the attic had always been a complicated one. As a child, I loved climbing the creaky stairs to search for dress-up clothes and fodder for make-believe. But it was scary up there; you practically needed a map to navigate your way through. There were ceiling-high metal file cabinets, rolling racks of dresses, framed old-fashioned photographs of people I knew were ghosts. It was not a place to visit after dark.

The door to the attic mysteriously locked from the outside. Local lore had it that the family who owned the house before my grandparents had a sociopathic son whom they’d lock upstairs when he misbehaved. When Mom and I first moved to Walla Walla, I remember sneaking up to the attic after school one afternoon and leaving the door open. My grandfather came along, and, not realizing where I was, shut the door and locked me inside. After the incident, I always left a sign for passersby: “Laurel is up here.”

That Saturday in late August 2008, I made my way up once again, reminding my mother where I’d be and wondering what, this time, I would find.

It was a hot afternoon and there was no air conditioning or fan, so I headed for the far corner near the window, hoping for a slight breeze. I weaved past a stroller, a pile of mismatched shoes, a wooden ski. I nearly tripped over my red Radio Flyer wagon and thought of the time I’d declared at seven years old that I was running away to become an Indian princess. My wagon and I made it as far as Pioneer Park four blocks away when I ran out of string cheese and courage and turned to make my way home.

At the window I strained to unlatch the rusty lock. Years of neglect had swollen it shut. As I struggled to prop open the frame, I caught sight of a box buried beneath a stack of textbooks and dusty drapes. It was labeled “WRH MISC.” I went to the box and removed the detritus. Plumes of fairy dust bloomed upward as I lifted the lid and peered inside. It was a stash of my father’s keepsakes that had remained quietly tucked away and forgotten since our move in August 1989.

The box was a coffer of lost time. It contained my father’s childhood collection of Indianhead coins, the student ID from his sophomore year at Colby, a stack of half-filled stenographers’ notepads with illegible geological charts and indices. I removed each item gingerly, fingered every article. I thought of the hands through which they had passed, speculated the possibility that his were the last to touch this fold, that page. In that moment it was as if we were reaching out from opposite ends of the void, Daddy and I. We were grazing fingertips.

As I burrowed deeper past an assortment of geodes, a box of slides, and a pile of correspondence bound by two yellowed rubber bands, I came across a tan pebbled leather journal with my father’s initials engraved on the front plate. I ran my thumb over the monogram and put the leather to my nose, inhaling its age and musk. Carefully, I turned open the cover and examined its contents.

Before me were the entries Daddy had scrawled during his trip to Canada in the spring of 1989.

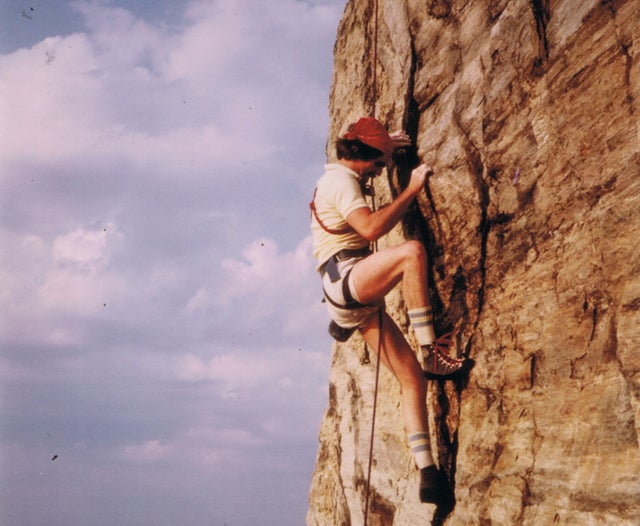

IT’S EASY TO QUESTION the sanity of mountain men. Surely no one in his right mind could look up at a mountain and say unironically, “Yes, I think I’ll attempt death today.” But for a climber, treading so close to the possibility of dying forces a man to act with his all. In those moments, balanced precariously on the edge, a man discovers the kind of person he truly is. Being that close to death, you might as well be touching God.

Mountaineering is not a hobby, it’s a religion, a way of life, a game to see how far you can go without killing yourself. To a climber, the overwhelming thrill is worth the incredible risk because, in the end, the greater the danger, the more it means to be alive.

I’VE NEVER HAD AS much clarity about my father’s obsession with climbing or his reasons for returning to Canada in 1989 as I began to have that summer afternoon sprawled on the floor of my grandmother’s attic. Until now, I’d never known the exact details of the trip, how he and Chris functioned as a team, the way their physical abilities measured up and the effect it had on my father’s psyche. As I poured over the journal entries, the rough sketch of events I’d had in my head for so long began to flesh out, and the picture began to fill.

On Easter Sunday of 1989, my father and Chris departed Boston for Calgary. The next day they rented a car and drove to Canmore, where my father’s good Austrian friend owned and operated The Haus Alpenrose, a popular climbing lodge he’d opened in the 1970s. When Daddy and Chris arrived at The Alpenrose Monday night, they socialized, ate dinner, and excitedly charted out their climbing schedule for the week.

From the way it looked in the journal, my father and Chris had planned a serious ice climb every other day, giving themselves a day of rest in between. With two full weeks in the Icefields, this gave them some latitude in the event weather was inclement for a day or two. Based on the itinerary before me, only the first week seemed to have been plotted with some degree of certainty. Ultimately, the daily climbs would progress in duration and difficulty, and the week would culminate with Slipstream.

During the first week together, Chris and my father struggled to negotiate their stride as a team. In spite of the strenuous physical and mental training they had undergone prior to the trip, my father constantly fell behind, was tired and worn. In the journal he continually mentioned how Chris climbed faster and was more agile on the ice. The morning they set out for Whiteman Falls—a two-pitch face known for its nasty overhangs and hollow, brittle ice—they encountered heavy snow during their ski to the base of the Falls. But the long ski in was an energy drain for my father, and I could read the frustration in the fervent slant of his writing. Here he was, fatigued already, and they hadn’t even begun to climb.

When they arrived at the Falls, Chris led the first pitch. My father tried to lead up the crux but got spooked by the steepness halfway up and retreated. Chris led the rest of the way through. Though Daddy’s commentary was minimal, I could tell he was embarrassed.

“I felt very bad,” he wrote, “but Chris didn’t make a big deal out of it. The climb was beautiful and in spite of my faux pas, we did it in good time and style,” adding, “My head is not into steep ice after laying off for 1 1/2 months.”

Two days later following a tranquil afternoon telemark skiing in Banff, the two headed to Polar Circus, a watershed located along the west face of Cirrus Mountain to the east of the Icefields Parkway. A far longer route than Whiteman Falls, Polar Circus features about nine total pitches that ascend 2,300 vertical feet, 1,600 of which are sheer waterfall ice. Due to its southern exposure, the ice on Polar Circus is prone to melt from the heat of the direct afternoon sun, causing it to crackle and pop. This renders the route both unpleasant and dangerous to climb once the sun is fully overhead. Because they’d had a few sunny days, my father and Chris wanted to be off the summit before the sun hit.

They began at 7:00 that morning, passing the lower ice with a traverse on snow. At the first sign of steepness, they geared up, and while Daddy was seconding behind Chris’ lead, two Banff climbers caught up to them. Chris and Daddy got into an unspoken race with the Canadians and beat them to the top. “We burned up,” my father wrote. “I was very tired.”

The two teams debated over who should continue up first. “Because we were third-classing,” my father wrote, “the Canadians agreed—though somewhat disgruntledly—to let us pass through.” And so Chris and my father proceeded up the pitch.

At the time I discovered these journal entries in 2008, I was unfamiliar with most of the technical terminology my father used to describe his climbs. Because I didn’t know what “third-classing” was, I pulled my iPhone from my back pocket and Googled “third-classing climbing terminology.”

This was the first result that Google yielded:

“Class 3 – n./adj. AKA Third Class. Denotes scrambling involving the use of the hands as well as the feet, but where a rope is not needed. More commonly used to describe climbing without a rope, especially when the climbers have [one].”

Perplexed, I re-read the definition, sure I’d misread it or had somehow selected the wrong link. I hadn’t. I refreshed my Google search and perused other sites that yielded results. They all said the same thing. To “third class” is to solo.

I looked out the window at the breezeless summer afternoon suddenly wishing I had a glass of water. I couldn’t understand what the hell the two of them were doing climbing without ropes. To me, the whole point of having a partner was to be connected to him, especially on a route that seemed so precarious. I didn’t get it. I went back to my phone and Googled “solo climbing benefits.”

What came up was an explanation of how soloing—namely climbing without a rope, without a partner, without protection, or some combination therein—is both the purest and most dangerous type of climbing. It explained how climbers opt to solo because it allows them to be in control of everything, and that as a direct result of the extreme risks involved, it allows a climber to push human limitations and satisfy a need for thrill and excitement. Soloing helps a climber better understand himself, the website explained, and tells him just how far he can go.

Swallowing hard, I looked down at the journal in my lap. For years I’d searched for answers like this—in photos, in stories, in letters. What made Daddy climb? I’d wondered. Why did he love it so much? And, I’d secretly feared, had he loved it more than me? Now here I was 19 years later, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to understand. That it all—a life, a love, a fatherless childhood—boiled down to adrenaline and ego made my mouth dry.

But then again, I thought, at least I knew where the story was going. I picked up the journal and read on.

The two men soloed—ropeless—up the first four technical pitches of Polar Circus as Chris led them higher along the frozen falls. On the middle of the third pitch, a chunk of ice came loose under his crampons and fell onto Daddy below. Because he was tired and his leg muscles were cramping badly, he angrily shouted at Chris to stop. Chris called down and asked if he wanted a belay. “No,” my father yelled up. “Just stop so I can avoid getting knocked off the ice!” (“Really,” Daddy confessed parenthetically, “I wanted a rest.”)

When they arrived at the top of the tier mid-way through the climb, they stopped to take a break and eat. After resting they continued on. There was no mention of roping up. Daddy led the first of the two middle pitches and finally began acclimatizing to the steep ice. “I was coming into it after all, even in my near exhausted state,” he wrote. I thought about what my uncle Tom had once said to me, about how there are those who fight and those who flow. My father was fighting so hard.

They finished the climb at 11:15 a.m. My father wandered up to the snow bowl above to collect his thoughts and reflect on the climb. He hadn’t been particularly challenged by the grade of the ice—“none of the pitches gave you a real airy feeling, and the difficulty was no more than grade four”—but he and Chris were climbing well and working out their differences. “Chris is obviously fitter than I,” he wrote with a bitter twinge, “but I am coming around mentally as well as physically and am finding my own pace.” It was clear his competitive spirit was irked by his physical limitations. It broke my heart to imagine my father like this, hindered but forcing himself through the hindrance, as if he had something to prove.

Their climb two days later up Weeping Pillar defused a lot of the frustration my father had experienced in the preceding days. The Pillar is a classic route that features six pitches ranging in steepness from grade four to grade six. It is considered by some to be one of the best ice climbs in the Canadian Rockies.

That day, my father and Chris finally settled into a groove. The weather was cloudy and cool, providing them with perfect climbing conditions. Though the ice was gnarly in places, the steepness was thrilling. Daddy grew stronger with each pitch, and by the time the climb was over, he and Chris had finally synced rhythms.

“Total adrenaline rush! Chris was jazzed, too,” he scribbled, adding, “We’re an excellent team when we are both climbing well.”

He went on, describing the exhilarating final pitch.

“A straight shot up a groove with good but technical ice. Many observers from below. We rapped the rock raps—incredible free hanging for 165 degrees off the top!”

I didn’t know what “free hanging” meant, but my mind conjured a man in the likeness of Tarzan gripping a dizzying overhang with one hand and victoriously fist-pumping the air with the other. I knew he was sorry to see it end.

On the way back to the car, they saw that their spectators had left them notes of admiration in the snow: “Totally awesome!” and, “Hey dudes, all right,” and then, “Will you give me a lesson?” Buzzed from the climb, my father wanted to return to the hostel where they’d stayed two nights before. A group of European climbers were lodging there, and he wanted to go back and brag about what he described as one of the most intense experiences of his life. So, under the pretext of having left extra gear behind, he and Chris drove down for a night of celebration.

At the hostel they encountered the men who had watched them from the base of Weeping Pillar. The group communed over beers and burgers, swapped climbing stories, and talked about their plans for the coming days. At the mention of Snow Dome, two Canadian climbers piped up and excitedly spoke of their recent adventures on the eastern face. “They gave us info on Slipstream that will prove useful,” Daddy wrote.

Hoping for more but fearing what came next, I turned the page. It was a blank.

Excerpted from the forthcoming memoir, Spindrift, by Laurel Holland, a Brooklyn-based writer and former actor. Contribute to the project’s (live until Thursday, July 12) or follow Holland’s progress on her blog, .