“FIFTEEN MINUTES,” growls Reinhold Messner, the king of all climbers. We’re standing outside his castle in the mountains of South Tirol, a region in extreme northern Italy that was once part of Austria. “I’ll give you 15 minutes. And then you must go.”

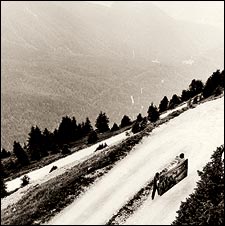

Lord of the Alps: Reinhold Messner in the Dolomites near Cortina, Italy, June 27, 2002.

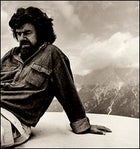

Lord of the Alps: Reinhold Messner in the Dolomites near Cortina, Italy, June 27, 2002. Stomping grounds: Messner on Monte Rite; Behind him are the jutting spires of the Dolomites, where the Great One learned his craft and still looms large.

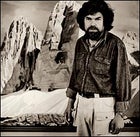

Stomping grounds: Messner on Monte Rite; Behind him are the jutting spires of the Dolomites, where the Great One learned his craft and still looms large. Messner en garde in his mountain museum: now 58, he says the Himalayan game is behind him forever.

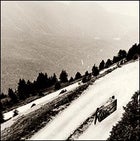

Messner en garde in his mountain museum: now 58, he says the Himalayan game is behind him forever. “A crosser of deserts”: Messner and an employee, lugging a museum mural near the Schloss Juval

“A crosser of deserts”: Messner and an employee, lugging a museum mural near the Schloss Juval

After traveling halfway across the world to see His Greatness, I resign myself to the strict time limit. It’s actually 15 minutes more than Ruth, his German-speaking secretary and merciless gatekeeper, promised earlier on the phone.

“Mr. Messner has no time,” she said. “Period.”

Now that I’m here, I can’t help but notice that Messner is a little uptight. The thick-bearded Tirolean, dressed in baggy bell-bottom slacks and a puffy long-sleeved shirt, looks like he’s about to lose his cool. Garden hose in hand, he’s trying to water some lilies. Underwear and T-shirts, the day’s laundry, flap vigorously in the wind. In a cradle on the ground lies a screaming infant, one of three children Messner has had with his longtime girlfriend, Sabine Stehle. (Messner has been married once before, and has a child from a previous relationship.) Weirdly, the whole scene is just a little bit Hee Haw.

But of course, it isn’t. This is a real castle, featuring the usual castle accoutrements: crenellations, towers, gated entrances, a few dozen rooms. Built in the 13th century and perched like a condor’s nest atop a steep mountain overlooking the family vineyards, the Schloss Juval is a beautiful and stately medieval pile. Messner is busy sprucing it up while moving Sabine and the kids in for the summer, as he does every year.

This is my second attempt to interview the reclusive Messner. I spent a hard-won hour with him three weeks ago, when Ruth relented after months of saying nein. I’ve returned, this time with an ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Television crew doing a documentary about the climbing legend. He’s allowed us to have quick glimpses all week, following him to political functions and a museum opening. Now he’s promised to reward me with a sit-down interview—assuming, of course, that he gets his chores done. And it’s not looking good. Messner, visibly frustrated, is squeezing his thumb hard over the hose’s nozzle. The water blasts forth, making loud thwapping sounds against the flowers. He cups his hand around his mouth and yells something in German to whoever is inside the castle.

Before long a teenage girl comes out to quiet the baby. Then, from inside the house, there appears a striking blond woman in shorts and a T-shirt. It’s Sabine. She flashes Messner a stare that says, Get moving, buddy.

“I told you I don’t have time,” he says, glaring at me. “I’m needed inside. I’m needed for housework.”

WELCOME TO THE GOLDEN YEARS of Reinhold Messner, 58, a man who, when he’s not doing chores, leads one of the more regal and hectic lives in all of sport. Twenty years after his heyday, Messner is still the most popular climber on earth. He’s the subject of dozens of books, not counting the 20 or so he’s written about himself. He’s a valuable commodity and an eager salesman, having pushed everything from yak steaks to sportswear. Outdoor festivals and book fairs pray he shows up, because he fills auditoriums. Young adventurers seek his esteemed approval for their own expeditions in hopes of basking in stray beams of reflected glory.

What’s the explanation for all this success? “Great things happen when man meets the mountains,” he likes to say.

Indeed, great things happened when Messner ventured into the high country, whether it was the Alps or the Himalayas, both of which he pretty much owned in the sixties, seventies, and eighties. No individual in history has done more to revolutionize climbing, and Messner has surpassed even Sir Edmund Hillary in his genius for capturing people’s imaginations, turning their eyes to the snowy ramparts of the world’s highest peaks.

Messner’s accomplishments are mind-boggling, and rank as some of the greatest in the history of any athletic endeavor. In 1978 he and Austrian Peter Habeler became the first climbers to conquer Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, something that was considered flatly suicidal at the time. He was the first person to solo Everest, which he did in 1980, again without bottled oxygen. By bagging 27,824-foot Makalu and 27,923-foot Lhotse in a single Himalayan season in 1986, he became the first to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. Along the way, Messner reinvented climbing with his mid-seventies introduction of fast and light alpine-style techniques to high-elevation routes. No extra oxygen, no fixed ropes, no established camps, no support teams—just a clean break from the siege tactics that dominated the game until then.

There are so many moments that bear mentioning, but most climbers say Messner’s most influential feat was his Everest solo, in which he scurried up the mountain’s North Face carrying everything he’d need on his back, returning to Base Camp in an astonishing four days.

“It was like landing on the moon,” says Conrad Anker, 39, an Everest veteran from Bozeman, Montana. “After that, everything else kind of pales in comparison.”

Lists don’t tell the whole story. Messner was a personality as large as the Himalayas themselves. When he summited a mountain, you heard about it. He was a living, breathing PR machine who expertly marketed himself all over the world. “He was cashing in on climbing while other people were just climbing,” says veteran British alpinist Adrian Burgess, 52. “Of course, he had something to cash.” Messner’s books have played a large role in his economic success. They aren’t the usual dull drivel of climbing journals. The best of them—including The Crystal Mountain and Everest: Expedition to the Ultimate—are deeply introspective works, often reading like Wagnerian psychodramas.

Later, when Messner set his sights on polar exploration, he broke new ground there, too, in 1990 becoming part of the first team, with German polar explorer Arved Fuchs, to cross Antarctica without assistance. Three years after that, he and his brother Hubert trekked across Greenland. Such accomplishments still astonish Messner’s elite colleagues.

“Reinhold Messner really is a great tour de force,” says Tom Hornbein, the 71-year-old U.S. climbing legend and physician. “He’s one of those people who shake paradigms.”

Peter Athans, a 45-year-old American climber who’s summited Everest seven times, says, “Reinhold simply changed people’s thinking. What he did was so far ahead of everyone.” According to Ed Viesturs, 43, the accomplished Seattle-based climber who’s trying to repeat Messner’s ascent of all the 8,000-meter peaks, his contribution was more fundamental than that: “He proved that your head does not explode if you go very high up.”

Of course, the man has always had his detractors. British climber Doug Scott, 61, once complained that Messner, while great, was a showman who packaged accomplishments that would resonate with the public—ˆ la the tidy-sounding 8,000-meter tick list—rather than doing truly cutting-edge routes. “Reinhold did some very good climbs,” he said. “But then he took some routes with very little technical difficulty, just to get up them quickly.”

Most criticism, however, has centered not on Messner’sbulletproof feats, but on his arrogant, brusque way of dealing with people. Although he’s known to be occasionally charming, he’s famous for his tirades and grudge-nursing, both on and off the mountain. After the 1978 Everest climb, he abruptly ended his 12-year relationship with Peter Habeler after Habeler published a book that implied Messner exaggerated his leadership role in their expeditions. The two have barely spoken, nor have they climbed together, since. Habeler—now 60, still climbing and living in Finkenburg, Austria—has publicly depicted Messner as a control freak who didn’t want anybody showing him up.

“We never had any problems as long as I was not making anything out of myself,” he said a few years after the climb. “It seems to me that Reinhold simply wants to be number one, and he doesn’t want anybody to be beside him.”

Possibly. But many people will tell you that Messner’s big ego is a big part of why he succeeded in the first place. “His arrogance is what made him so strong and focused,” says Viesturs. “He walked his talk, like Muhammad Ali.”

“Like him or not,” says Greg Child, 45, an author and veteran of many Himalayan climbs, “all roads lead to Messner.”

AFTER TAILING MESSNER off and on for a month, I think I’ve caught on to the Reinhold M.O.: Act aloof and expect the world to roll over. To do this, he uses a full array of dramatic tools, one of which is talking very loud. But the histrionics get old. Eventually you just want to grab him by the lapels and tell him to cool it.

Messner has shown signs of lightening up in his recent books, where he gives the reader a glimpse of the core emotion that rules his life: loneliness. Odd, one might say, for a climber who’s made a life of venturing alone to the world’s most dangerous mountains. But if you soften him up, Messner will tell you that his life has been a struggle, in part, to overcome his fear of solitude.

“I was trying my whole life to be able to handle it,” Messner tells me during one of our talks. “I am not made for lonely expeditions. In the sixties, I climbed during the day so I wouldn’t have to be alone. I finally learned to stay up for weeks in the high altitude all by my own without being afraid.”

I ask him why, then, he has alienated so many people. Why has he not spoken to Peter Habeler for so long? His answer is revealing.

“Out of all the climbers of this generation,” he says, “I was the one who became known to the larger public. Many of them—not all of them, but many of them—understood they had only one chance to use me for their personal gain. And it’s very easy to use me. We do it on the shoulders of Messner, they say. And this is possible; I can carry many people. But it’s not possible if they shit on me.”

Messner declines to say who exactly has abused him, only that his patience wears out. “After a while I say, OK, I do it by myself. But you know, I’m not willing to be cheated by people. Maybe once, but not twice.”

His living-legend status is a mixed bag for Messner. “Fame is very heavy,” he sighs. “When there are large crowds, I’m unable to handle it. I do not like to speak with one person and five others are pulling me away. It makes me crazy; I won’t talk to you. If people are eating me up, I get aggressive and I’m going away. Nobody can force me to destroy my own life because somebody is trying again to use me.”

The topic turns to what’s left to do in his life. Messner has given up Himalayan climbing. He abandoned a 1996 attempt on 26,360-foot Gasherbrum II because the base camp was overrun with people. A 2000 bid to put up a new route on Nanga Parbat was hampered by bad weather, and he didn’t make the summit. But he says he’s planning a major expedition for 2004, similar to his 1992 crossing of the Taklimakan Desert in China.

Details? “I will be crossing a desert” is all he’ll say.

Meanwhile he’s serving out a term—which ends in 2004—as an Italian representative to the European Parliament, the governing body of the European Economic Union. And he remains a tireless spokesman for the preservation of mountains and mountain cultures. To house his legacy, Messner is building four museums in Italy that will display much of his climbing paraphernalia. Two are complete: a display of Tibetan art at Castle Juval, and the recently opened Messner Mountain Museum, which is devoted to the Dolomites. In the future he hopes to build facilities focusing on high-altitude climbing and mountain cultures worldwide. He says he has divided his existence into six “lives.” The first was his vertical, or rock-climbing, life. The second was his high-altitude life. The third was his polar life. The fourth was his life investigating the myth of the Himalayan yeti, about which he wrote a controversial book. The fifth is the politician’s life. The sixth is retirement.

“A 30-year-old rock climber is an old man,” he says. “At 40, one is in the middle of his high-altitude power. At 50, a crosser of deserts is at his best age. But at 60, each of us is out of the game.

“Right now,” he adds, “I must finish up my term in the European Parliament. I’m working on a book on the evolution of rock climbing. I have my museums. I will probably make an IMAX film with some Americans. Maybe a seventh life is coming. Maybe it’s to go live in a cave somewhere and forget about everything, like my hero and favorite philosopher, Milarepa, the Tibetan thinker who always lived in a cave.”

Really? Reinhold the Hermit? “OK, maybe I will not stay in one cave,” he smiles, “but I will live at least part-time in a cave.”

We walk outside, and I ask him if he’s prepared for old age. He opens with the words “I am afraid…,” and I think I’m going to get a candid response, but then he backtracks.

“Actually,” he says, “starting to get old is perfect. I’m feeling the effect…but getting old means getting freer. I don’t have to have successes. Sure, I will stay with my family…but I will retreat. I will again be my own ruler, like when I was a child.”

THE DOLOMITES ARE GIANT, rugged minarets of limestone that jut 12,000 feet out of the green valleys of South Tirol. They, more than any person or thing, shaped Reinhold Messner. Born to a Roman Catholic family in 1944 and raised in the tiny village of Villn├Âss, he climbed his first mountain, an 11,000-foot cone of rock called Geisler Peak, before age five.

Climbing had become an obsession by his teen years. The young idealist rejected the new practice of drilling bolts into the rock to make difficult climbs safer and easier. Instead he used the smallest amount of gear possible, usually just a rope and a handful of pitons. “The impossible doesn’t exist anymore,” he fumed in a local newspaper. “Why dare, why gamble, when you can proceed in perfect safety?”

In 1967 Messner enrolled at Padua University, where he climbed with his younger brother, G├╝nther, in the Dolomites and elsewhere in the Alps. He graduated four years later with an architectural engineering degree.

But the big mountains called. In 1970 Reinhold, then 26, and G├╝nther, 24, signed up for their first Himalayan expedition, to the ninth-highest peak in the world, Pakistan’s 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat. Led by Karl Herrligkoffer, a notoriously strict Austrian, and run with traditional siege tactics, the expedition was not Messner’s preferred style. But he badly wanted the experience, not to mention the prize: Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face, the highest continuous rock-and-ice wall in the world.

Bad weather plagued the climb, but Messner was ultimately given a chance to go for the summit alone. On the way up he looked back, and was surprised to see G├╝nther on the ice face below, scrambling to catch up with him. Reinhold waited, and the two proceeded to the summit together. At the top, it became clear that they would not be able to return to their high camp before dark. Showing signs of altitude sickness, G├╝nther was unable to head down.

What happened next is in dispute. According to Reinhold, after an overnight bivouac at 25,000 feet, he made a fateful judgment call. The Rupal Face was too steep for G├╝nther, so he decided that their only chance was to climb down the other side of the mountain on the less steep Diamir Face. G├╝nther, he felt sure, would recover as they descended.

As they slowly picked their way down, temperatures warmed, conditions improved, but G├╝nther showed little sign of recovery. They spent another frigid night on the mountain. The next morning Reinhold instructed G├╝nther to wait while he went ahead to scout out the best route. Reinhold says that, just minutes later, an avalanche swept G├╝nther away. Though he scoured the mountainside, he found no trace of his brother. Crawling desperately on all fours, he continued down the face until he reached a meadow where two local Pakistani men came to his rescue and took him to their village.

This was not the Himalayas 101 course that Reinhold had hoped for. He had lost his younger brother, and doctors soon amputated seven of his badly frostbitten toes. To make matters worse, newspapers and other expedition members blamed him for his brother’s death, a pattern of recrimination that continues today. Following the recent publication of Messner’s German-language book The Naked Mountain: Nanga Parbat—Brother, Death, and Loneliness, several climbers who were on the mountain when G├╝nther died, including Germany’s Max Engelhardt von Kienlin, are now publicly questioning Messner’s version of events and accusing him of being more concerned with his own mountaineering ambitions than with his brother’s safety.

The climb still haunts him. “Nanga Parbat changed my life forever,” he tells me. “But I had to take responsibility and live with the tragedy. In the end, my brother died. I was lucky to survive. I learned to accept death in the mountains.”

Messner’s career had reached a transformative point. “Without my toes, I could no longer climb on the rock at an elite level,” he says. “So I became a mountaineer.” He soon joined up with Habeler, whom he’d met during a climbing trip to South America in the mid-1960s. Habeler was slightly built, like Messner, and shared Messner’s strong opinions about what constituted respectable tactics. The two immediately took the sport by storm. In 1974 they climbed the north face of the Eiger in ten hours, destroying the previous record of nearly 20 hours.

When it came time to make their biggest statement, there was only one choice: Everest, without supplemental oxygen. Scientists and doctors of the day said it was impossible. But Messner, having climbed extensively above 8,000 meters without bottled oxygen, thought the odds were pretty good. True to his stubborn personality, he would not back down.

On May 6, 1978, Messner and Habeler set out from Everest’s Camp II, and within 48 hours they were trudging through the snow up the Southeast Ridge toward the top. Messner later described feeling as though he were “nothing more than a single narrow, gasping lung, floating over the mists and summits.” On May 8, between 1 and 2 p.m., Messner and Habeler topped out.

They’d proved the experts wrong, and nobody was more surprised than Peter Hackett, a doctor who was on Everest at the time. A medical team had tested Messner for VO2 max and other factors, and Hackett recalls today that Messner “was physiologically very average,” considerably less fit than most elite climbers are now. “There is nothing you can pick out that is very remarkable about him,” he says.

Over the next five years, as Messner piled up climbing accomplishments, he accrued hundreds of thousands of dollars from his books and endorsements. He also became increasingly isolated. Other climbers were jealous of his money and fame. The public grew tired of his bull-in-a-china-shop ways, though his books continued to sell. By the early nineties rumors had begun to circulate that, as a result of all the time he’d spent at altitude, Messner had lost some mental capacity. He spoke of high-altitude hallucinations and launched an effort to discover the reality behind the Himalayan lore of the abominable snowman, or yeti. Whatever the reality, Messner’s growing fame was inextricably bound to controversy.

NOTHING HAS BROUGHT Messner more derision than his 12-year yeti investigation, which concluded in 1998 with the publication of his book My Quest for the Yeti: Confronting the Himalayas’ Deepest Myth. But when you look closely, you find that what Messner did wasn’t especially weird, and certainly doesn’t seem like the product of a compromised mind.

In his book, Messner recounts how he chased large, furry animals all over the Himalayas in hopes of getting to the truth about the mysterious creature. He claims he first saw a yeti in Tibet in 1986, while trekking alone through the forest of the Mekong River valley. He described the creature as tall and menacing, “its face a gray shadow, its body a black outline.” Covered with hair, it appeared to be more than seven feet tall. It stank horribly.

Unfortunately, Messner didn’t come back with any proof of this bizarre episode. The creature ran off before he could photograph it. When he returned to civilization, he hit the books to learn about the origin of the age-old yeti myth. He decided there were two yetis: one living in people’s imaginations, the other a real animal living in the high forests of the Himalayas. “I am searching for the animal that gave rise to the yeti legend,” he wrote.

That distinction was lost on the public, which seemed amused by Messner’s quest. Soon he was labeled a crackpot, possibly a delusional one. “Only when I returned to Europe did I realize to what extent my words had been misunderstood,” he wrote in My Quest. “Self-proclaimed yeti experts declared me insane. More upsetting, some fellow climbers seemed to think my yeti search was a publicity stunt.”

Unbowed, Messner advanced a theory: The yeti, he argued, was the rarely seen Himalayan brown bear, a nonmythical animal known to inhabit Tibetan forests. Messner remains convinced he’s solved the mystery once and for all.

“You will see,” he said to me. “Fifty years after my death, people will say this is the answer. There is no other answer.”

Messner followed up that project with another unorthodox book, this one about British mountaineer George Mallory’s attempts to climb Everest and his 1924 death on the mountain. It’s called The Second Death of George Mallory, and its impetus was the 1999 discovery of Mallory’s body just below Everest’s North Ridge. That discovery, by a team of Americans led by Eric Simonson of Seattle, fueled much discussion about Mallory’s fate, as well as speculation that Mallory might have made it to the summit before succumbing.

This incensed Messner, in part because he didn’t think Mallory was skilled enough to handle the Second Step, a steep rock outcropping near the top. He also believed that, somehow, finding the body at all violated the mystery of what happened to Mallory and his partner, Andrew Irvine. Removing this magic from the equation constituted Mallory’s “second death.”

It’s a harmless if eccentric argument, but what really irritated critics was the book’s style. Messner constructed the story as a narrative told in three different voices: his own, Mallory’s voice at the time of his climb, and the voice of Mallory’s ghost. The ghost is rather cranky, not unlike a certain Tirolean superman. “How strange to have one’s death announced to the world by satellite,” the wraith complains. “Oddly, I have never felt more alone.”

All of which prompted one critic to snipe, “Jeepers, Reinhold. You might be the Michael Jordan of climbing, but, trust us, public channeling of dead British climbers is a sure sign of oxygen deprivation.”

Messner shrugs off the censure. “I know they say I am, how you say, unbalanced,” he says. “They can’t believe it’s me with more new theories. They say, ‘Why Messner again?'” He pauses. “I say Mallory was just a beautiful story, and he was a great man. I liked him.”

LOW, GRAY CLOUDS are spitting lightly on the Dolomites, and we’re on the side of Monte Rite, a grassy, steeply sloped peak that houses the Messner Mountain Museum. It’s evening, and though the man isn’t giving interviews tonight, he has allowed a dozen local reporters to follow him around as he plays yak-wrangler, releasing a small herd of gnarly, chocolate-colored Tibetan yaks onto the property. The plan is to unload the excitable beasts from a cattle trailer and then lead them down a steep trail to a meadow. There they’ll stay and, Messner hopes, reproduce. Their offspring will be served up in Messner’s Yak & Yeti Restaurant, located in the town of Sulden, about a three-hour drive from here.

All has been going smoothly until now, when the 300-pound horned beasts stop in their tracks and refuse to budge. They look like they might charge Messner, who is several yards down the trail, wearing a bright-purple windbreaker and carrying a walking stick. Sensing trouble, he turns and stretches his arms, cradling the staff in one hand. He makes loud, guttural grunts, sounding like a silverback gorilla.

“Heah, heah!” he says. “Heah! Heah!”

The noises seem to work: The yaks submit to this fearless cowpoke. The cameramen scramble to snap photos of the scene, and Messner, steely-eyed and determined, leads the animals downward until they stall again. So he repeats the performance.

This scene gives me another important glimpse into the Reinhold M.O.: When creatures don’t bend to your will, herd them. I get a direct application of this style one day when Messner offers to take me on a short tour of the house.

“Come,” he commands, as we leave an empty room off the castle’s kitchen. We go outside, where a stream of tourists—the castle is open to the public for $7 a person when Messner isn’t in full-time residence—is still making its way from the entrance through the grounds.

I follow Messner as he threads through a small crowd, becoming smothered in the joyful praise of autograph seekers. Leaving them behind, he leads me into a cold, dark room that is lined with postcards, books, and videotapes, all either about Messner or pasted with his noble, windblown likeness.

“You can buy some things here at the gift shop,” he says quickly. “I think you will be liking it. Thank you for coming.”

And with that, he’s gone—he disappears inside his castle. Of course, I can’t resist. I buy several postcards, and then I get ready to go back to my hotel in the valley below. Upon bidding farewell to the castle, this strange fortress, I’m surprised to find that the tour bus that brought me up the mountain earlier has stopped running for the day. So I have no choice but to trudge back to town down a steep, switchbacked road.

I don’t mind. It’s hot, but the scenery is beautiful, the massive peaks jutting out of the ground like giant molars, the lush green valleys crisscrossed with small farms. I’ve just rounded the first switchback when a tan Opel, spitting up dust and rocks, appears behind me. I turn around and see that it’s the king of the castle, sitting in the passenger seat next to a driver.

I assume they’ll stop to pick me up, but alas, the Opel isn’t slowing down. In fact, it’s speeding up. Then it swerves around me and continues accelerating down the mountain, kicking up a cloud of dust that takes several minutes to clear.

After a few minutes I can’t see the car anymore, but I can hear its buzzing motor carrying Reinhold Messner, happy and mad, into the future.