When a The North Face expedition team made up of Conrad Anker, Pete Athans, Kristoffer Erickson, and others set out to Nepal in April 2005, its biggest challenge wasn't climbing a 21,128-foot Himalayan peak called Cholatse. It was helping Dr. Geoff Tabinan American ophthalmologist and founder of the Himalayan Cataract Projectto perform cataract surgeries on 255 blind villagers. The story of the team's medical work and high-altitude climbing became the subject of an ���ϳԹ��� feature story (see “The Light of the Seven Mountain Suns,” December 2005), and a

Preview Light of the Himalaya

to watch a preview of Light of the Himalaya, as well as trailers for other films by Michael Brown.��

���ϳԹ���: You're most well known for your film Farther Than the Eye Can See about the 2001 Everest summit bid of blind climber Erik Weihenmayer. Seems like the stories behind eyesight and mountains make for good films.

Brown: Expeditions lend themselves well to story telling. I've studied Joseph Campbell and other storytelling types. I look for those elements in a story that keep it interesting. The hero's journey is a great beginning point for any storythe hero goes to an extraordinary world and comes back with some great wisdom. But then, when you're there, climbing is cool and we love it, but compared to the eye campsthey're the most profound things; it was astounding.

For this film, you traveled by bus from Kathmandu to Jiri, then trekked to Kenja, deep in Nepal's Maoist territory. Any dangerous encounters?

It was a little nerve wracking. A couple days before we got there Maoists had thrown a pipe bomb through the window of a taxi and it blew up and hurt two Russians. We ended up interviewing them for the film, talking about what happened. The Maoists are kind of an undercurrent in the film. They give it a little edginess, a little danger. We're going in to do these eye camps in areas Maoists really controlled, but they never bothered us. They knew who we were and what we were doing, and chances are those doctors were doing cataract surgeries on the parents of the Maoists.

Those surgery scenes made me squeamish. You must like watching shows like ER.

No, I don't get a chance to watch ER. I generally get really queasy. We shot about 15 surgeries. At first, I felt a little sick, but after a while, it was easy to watch. We ended up adding a sound effect to the cataract coming outa squishing sound.

The North Face athletes were responsible for changing bandages, helping transport patients, and putting antiseptic on their eyes. Was Conrad Anker a good orderly?

He was. As time went by, Conrad and the others got into it. The Nepali people are so warm and easy to talk to. There's a special kind of ease of interaction with them. These people come from surrounding villages. They come to this schoolhouse, where there's very little as far as infrastructure. You have to feed all these people; you have to take them to the bathroom.

I bet climbing felt a little trivial after that. How was the view at 21,000 feet?

I've been up Everest three times and never on Everest have I encountered that kind of terrain. It was really steep and the exposure was just wicked. You looked at your feet and you could look right past them for thousands of feet down.

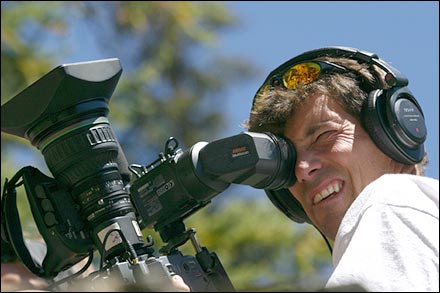

You were the first person to bring a high definition video camera to the summit of Mount Everest in 2001. What else did you fit in your pack for this climb?

We brought four HD cameras up Cholatse. And the big cameras weigh about 25 pounds. Conrad carried my extra water and my down parka, and I carried the camera, and my first water bottle, and maybe a snack. A lot of these guys are like thatthey'll help you. It's not just a camera crew and a climbing crew.

So, what's next for you?

I'm working on a film called The Endless Knot, about the Khumba Climbing School, which was started by Conrad Anker and Jenny Lowe in memory of Alex Lowe, who was killed in an avalanche on Shishapangma in Tibet in 1999. The story follows what life is like after Alex died and the relationship between Jenny and Conrad.