Tommy Caldwell and the Psychedelic First

Tommy Caldwell needed a challenge, so he decided to hoist his clanking gear rack and free-climb one of Yosemite's hardest routes—a punishing 5.14 called Magic Mushroom—in 24 hours or less. Matt Samet was there from start to finish to watch the planning, training, and performance of a superhuman athlete at the top of his game.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

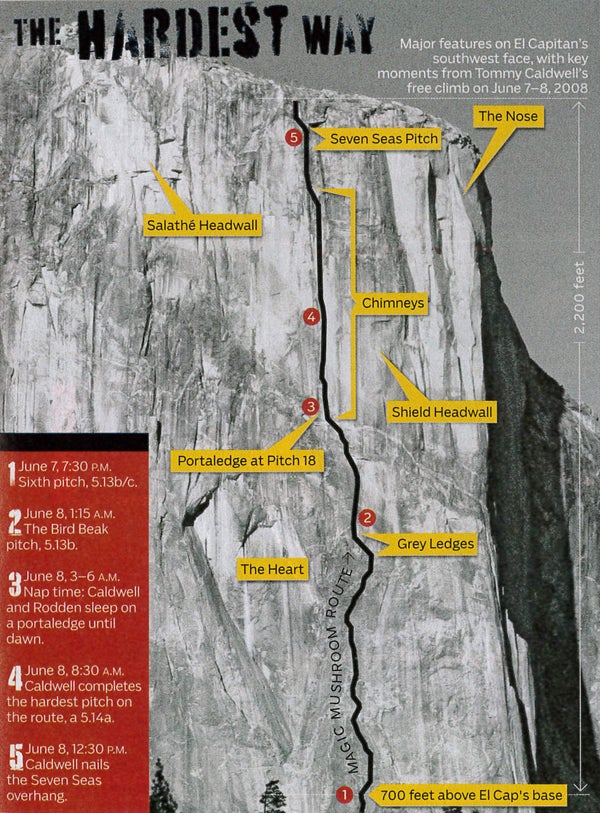

Earlier this year, while thinking about various fun ways to spend the spring climbing season in California, Tommy Caldwell settled on a doozy: First, he and a partner would try the most continuously difficult big-wall free climb they could find, a 28-pitch route up Yosemite's El Capitan, called Magic Mushroom, which looked to rate a 5.14. Then, if all went well, Caldwell would return to lead every rope length himself, during a 24-hour supported speed run.

The origins of the project went back much further than that, though, and it's fitting that Caldwell's grand notion came to him when he was collapsed inside a tent, completely wasted after 24 hours of climbing few others could have even attempted, much less pulled off.

It was October 2005, on a warm, dry day in Yosemite, and Caldwell had just stacked up a pair of 3,000-foot free climbs on El Cap, making all his vertical progress using nothing but the strength of his body and limbs, the gear there only to protect him in case of a fall. His wife, renowned climber Beth Rodden, along with a pack of friends and climbing media, had met Caldwell up top, where his arms were so flushed with blood and lactic acid that they'd gone numb. Three weeks later he developed cluster headaches, and for more than a month his left elbow refused to straighten.

Caldwell had set out at just past 1 A.M. on October 30, starting on the Nose, a 2,900-foot 5.14a and the first line ever climbed on El Cap, back in 1958. (See “Number Crunching,” page 108, for a guide to climbing's rating system.) It was originally done by a cantankerous road surveyor named Warren Harding as a direct-aid climb, in which the climber puts weight on his protection hardware as he ascends, standing in stirrups called etriers to place each subsequent piece. Harding and various partners had needed 45 days over two climbing seasons. Caldwell, with belaying assistance from Rodden, did it in 11 hours. While he spidered up the wall, she managed the ropes rapid-fire in his wake, using self-ratcheting ascending devices called jumars as she pulled out the protection he left behind hand-placed metal widgets called nuts and cams. After jumaring the length of the rope, she'd stop to belay his line at each new anchor as he led off onto the next rope-length pitch.

At 1:36 P.M., Caldwell went back down to El Cap's base and swapped partners, moving on to the 5.12d Freerider with Chris McNamara, a California-based climbing-guidebook publisher. Around 9 P.M., 28 pitches up Freerider, Caldwell came to a final obstacle on a smooth, 5.12 dihedral a 90-degree, open-book-shaped convergence of two vertical faces. McNamara watched as Caldwell, after two falls, began to “stem” his way up the smoothest part of the dihedral, placing his legs in a splits-style bridge position, crab-walking as he applied force on the opposing walls. He made it through on his third try, going on to summit at 12:26 A.M. on Halloween.

The physical toll of this twofer was clear: Up in the summit tent, Rodden stood watch for two hours, waking Caldwell periodically to make him eat, so he'd have energy for the treacherous scramble and rappel down the East Ledges.

Even in his exhausted daze, Caldwell realized something: He could have pushed harder. Seventy percent of the climbing had been “only” 5.10 or 5.11 no-brainer stuff for an elite climber. What he really craved was an El Cap climb so relentless, pitch by pitch, that to do it in less than 24 hours would demand not only his best physical efforts but also a complicated mental and logistical game.

It would take him another three years to find the right target, and the project he settled on Magic Mushroom was a challenge for the ages. I'd heard about Caldwell's ambitions, and I wrote him to propose that he let me watch him plan and train from start to finish. He agreed, and I got a backstage pass while he rehearsed the climb of his life.

Caldwell was born on August 11, 1978, in Loveland, Colorado, the younger of two children. Lean at five foot nine and 150 pounds, he has the “climber V” highly developed latissimus dorsi muscles and much of his upper-body strength is concentrated in his shoulders. Watch him on rock and you see a whippety, swaybacked technician, his feet sticking to the stone as surely as if he were kicking steps in snow. (Contrary to popular belief, climbing isn't only about upper-body strength the best climbers rely mainly on savvy movement, propelled by the feet, legs, and core.)

Caldwell came to the sport through his father, Mike, who lured him at age three up his first multi-pitch route, above Estes Park, Colorado, with the promise that they'd fly a kite when they topped out. A senior guide at the Colorado Mountain School, Mike moved his family to the windy, spartan town and set out to raise an all-star. Tommy earned “credits” for training push-ups, pull-ups, sit-ups applying these toward candy bars and, later, rock shoes. He was only 12 when he first climbed the Diamond, a sinister 1,000-foot wall on nearby Longs Peak.

Throughout the nineties and into the new century, Caldwell left his mark all over Colorado. But he's best known for his unique rapport with El Capitan, a granite wall so intimidating that it sends many accomplished climbers scurrying back to earth. El Cap 100 million years old, two miles wide, scoured to near perfection by glaciers is home to 90-odd aid climbs and 17 free climbs. Over the years, roughly two dozen people have died there in rappelling mishaps, jumar accidents, and falls, or as a result of massive Sierra storms that can turn the cracks into cataracts or freeze ropes into unusable cable.

Caldwell first caught the El Cap bug in 1997, at 19, during a spectacular failure of a trip with his father, when he attempted to free the Salathé Wall, a 30-plus-pitch climb on the southwest face. The Salathé is hardest on the headwall, a golden shield of rock slashed by a 200-foot crack that consistently overhangs five degrees past vertical, 2,500 feet off the ground.

Caldwell craved an El Cap climb that was so relentless, pitch by pitch, that it combined his best physical efforts with a complicated mental and logistical game. He thrived on the buildup of 'adrenaline, emotion, fear, and excitement.'

“I didn't have the stamina, and we didn't have the logistics,” Caldwell says. “I'd be climbing with a 30-pound rack, a triple set of cams on one side and four sets of nuts and Tricams on the other.” The pair topped out after seven days, with the younger Caldwell having been, he said, “completely bouted” on the hardest free pitches, despite his 5.14 sport-climbing background.

Caldwell had tried the Salathé “on sight,” starting from the ground and attempting each pitch with no prior knowledge of how to do it. What he didn't know is that big-wall free climbers often spend time studying a route in advance, rehearsing it and setting up gear stashes. It's not uncommon to aid-climb or rappel the hardest pitches first, placing top ropes to make move-by-move rehearsal easier as the preparations continue. Climbers write down each gear placement and pocket these lists to consult on the fly; store food, water, and sleeping bags to obviate the muscle-crushing drudgery of hauling it all up from the ground; and tote or stash multiple pairs of rock shoes, some sized amply for easier pitches and others toe-crunchingly tight for the hardest leads.

Armed with this newfound knowledge, Caldwell returned in early 1998, humped 80 pounds of gear up the East Ledges, and rapped into the Salathé Headwall to rehearse the crux crack. He returned that April with Mike Cassidy, a climber he'd met in Yosemite Valley, and free-climbed the Salathé in a three-day push.

Since then, Caldwell has spent upwards of 500 days on El Cap, freeing 12 of its routes five of those being first free ascents. In 2007, to be closer to what he calls his “obsession,” he and Rodden took eight months off from climbing to build an airy, three-story, peaked-roof home in Yosemite West, only 12 miles from their theater of operations.

In early 2008, Caldwell set his sights on Magic Mushroom, which was first done as an aid climb in 1972 by Canadians Steven Sutton and Hugh Burton. The route follows thin but direct cracks and flared dihedrals up a steel-gray swath of rock that rises to the left of the Shield Headwall, a mammoth, gold-streaked swell on El Cap's southwest face. Caldwell's friend Adam Stack had tried and failed to free the line in 2004 and 2005, after El Cap veterans Alex and Thomas Huber, brothers from Germany, had inspected it on rappel and declared it impossible as a free climb. Caldwell had been working on a free version of Mescalito, a line near the Nose, but it had so many upper-5.13 and 5.14 pitches in a row that he couldn't see doing it quickly. Magic Mushroom seemed feasible by comparison.

Most of El Cap's free routes follow the more obvious natural crack systems. To free-climb them, you have to be adept on all crack sizes, from “sickly tips” (pinky locks) to “off-width” (wider than the fist but not big enough to shimmy up inside) to narrow chimneys that require full-body squeezing and groveling. Many of the hardest free cracks in Yosemite feature “pin scars” boxy, finger-size holes left behind by the original aid climbers, who repeatedly hammered pitons into the rock.

To protect against the sharp crystals in the cracks, free climbers often wrap their mitts with athletic tape. Where the cracks pinch down, they need to be strong on the glacier-polished grooves, slabs, and dihedrals, sections so glassy and holdless that climbers talk about “oozing” upward. El Capitan, with its notorious glacier polish and diamond-hard granite, has many such sections.

Big-wall climbers, free and aid alike, use well-refined tools to make wall life more tolerable: portable ledges for sleeping; ballistic-nylon haul bags filled with food, clothing, and water; lead lines and haul lines; hauling pulleys and jumars; hanging stoves; headlamps; and wall gloves. Even so, wall climbing is miserable and scary. The wind howls, you're dive-bombed by swallows, and, from just 500 feet up, giant trees on the valley floor look like matchsticks. To succeed, it's essential to have a solid, motivated partner.

For his first attempt on Magic Mushroom, Caldwell drafted Justen Sjong, 35, a professional climber based in Boulder, Colorado, who, like him, would try to free-climb every pitch. Prior to this year, Sjong had freed three El Cap routes, including one 5.13d first ascent, the preMuir Wall. All told, he estimates he's spent 300 days on the cliff.

Originally from Washington State, Sjong strayed into climbing at 19, transforming himself from redneck boulder scrambler to hardcore purist. Back in his Washington days, he kept a three-by-two poster on his bedroom wall that listed his climbing goals and read, in big, red letters, WAKE UP, DUMBASS YOU CAN'T GET GOOD BY SLEEPING. He apprenticed at the rain-soaked Index Town Wall, a granite bluff 50 miles northeast of Seattle. He'd drive there to aid-solo at night, by headlamp. He'd climb in the ubiquitous rain, with his jacket sleeves duct-taped to his gloves and wearing green rubber overalls, kneepads, and a fur hat with earflaps. In Colorado, to prepare for the cold mornings on Magic Mushroom, Sjong awoke early on winter days to self-belay on 300 feet of meat-locker-cold rock in Eldorado Canyon.

Magic Mushroom would be his and Caldwell's first major wall together, and they decided to go “team free”: They'd swap the lead position, but each would have to free-climb all the pitches. If one climber stalled, the other would have to wait, patiently belaying. In other words, one partner's failure could derail the whole effort, and Sjong told me his main worry was slowing Caldwell down.

To understand what it takes to free a big wall in a day and why anybody would want to it helps to look deeper into El Capitan's climbing history, which has involved endless experimentation, the occasional quantum leap, and a basic human need to go faster.

Until Warren Harding came along, climbers essentially ignored El Cap, because its sheer size outstripped their knowledge and tools. But his '58 ascent opened the door, and over the past 50 years, every climbable square foot has been picked over. Another major advance climbing the Nose in a day was made by a team of three top climbers moving together up the wall, in 1975. In 1988 came the first free ascent of the Salathé Wall. Another big year was 1993, when Lynn Hill freed all 33 pitches on the Nose.

Caldwell wanted a route that would push him to the limit while pitting him against the clock. “The whole idea of doing something like this in a day seems arbitrary,” he admits, but he says there's a sense of history to it, along with a tangible rush that comes from climbing such a big rock so quickly. “There's this buildup of adrenaline, emotion, fear, and excitement,” he says. “It's the most intense experience I've found in climbing.”

To do Magic Mushroom in less than 24 hours, Caldwell would have to marry his free-climbing skills with speed, organization, and superhuman fitness. To get into peak shape, he returned to a model he'd self-prescribed for the 2005 double day. That year, living in Estes Park, he'd first spent three weeks building a power base, to give himself the muscular “snap” needed to whip through the hardest sequences. He did this by bouldering, either on the overhanging gneiss of Rocky Mountain National Park or on a climbing wall at his parents' house.

Next, he spent a week working on stamina the ability to pull off hard moves even when pumped. Caldwell then added weight lifting, campusing arms-only motion up a special dowel board designed to build the upper-body strength needed to nail dynamic precision moves on the rock and a three-hour, 20-mile, 4,000-vertical-foot bike ride to 12,000 feet. By the end, a full-bore training day involved two hours of bouldering; a drive to a Colorado wall called the Monastery, where Caldwell would hammer out half a dozen climbs between 5.12b and 5.14b; a session in Estes Park's fitness gym; and that evening bike ride.

In California during the winter of 2007 2008, Caldwell flung himself at Yosemite's hardest boulder problems, toughening his skin and strengthening his grip on the blocks' sharp holds. He threw in endurance work at a rhyolite cliff near Sonora, pumping out five or six pitches of 5.13c to 5.14b per day. He used the home gym to perform laps on artificial holds, sling iron, campus, and do pull-ups. He also cycled on the steep, two-lane roads near Yosemite West.

When Sjong came out, in April, Caldwell was almost too ready for a climb that would require slowing down to make a team push. But Caldwell knew that if the team effort worked out, he might just be ready to climb the whole thing in a day.

It's April 15 a good six weeks before hot summer weather slams shut the El Cap free-climbing window and Caldwell and Sjong are in Caldwell's garage, sorting gear after their first two days of exploratory climbing on Magic Mushroom. It's early in the season, and hardly anyone else is on the wall; there's no competition for this climb. Nonetheless, Caldwell and Sjong keep their heads down, avoiding any preemptive announcements of their plans to anyone but wives and close friends. Their strategy during the month they'll spend learning the route is simple: Hike to the top of El Cap, spend the night, and then, at first light, rappel in and rehearse the upper 1,500 feet, where overhanging headwalls rear above the apron of less-than-vertical slabs below.

High on the wall, they'll evaluate the free possibilities, learn the moves, and plan the placement of hardware. They'll start early every afternoon at around two o'clock, the sun smacks this part of El Cap, heating the stone and causing the climbers' hands to sweat, reducing friction. They'll climb in two-day blocks and then descend to rest at Caldwell's house, refueling on Rodden's home-baked chocolate-chip cookies.

So far, moving individually, self-belayed by hauling pulleys called Mini Traxions, the pair has assessed a 1,000-foot section of obtuse, flaring chimneys (“bombays”) that begins two-thirds up the wall. Organization and studious ropework have been key to rigging the worker lines. Sjong says you can't just drop a 1,000-foot rope it can hang up on ledges or in cracks, and it might have to be cut. Instead, the climbers tie their static lines (non-stretching rope) into a belay station every 150-odd feet, using a knot Caldwell calls a super 8. This is a figure-eight-shaped knot tied on a doubled-over length of rope, with loops big enough to clip in to each anchor point separately, equalizing the load.

Magic Mushroom demanded superhuman fitness. Near the end of Caldwell's training, his regimen involved weight lifting, bouldering, half a dozen difficult rock climbs, and a bike ride on the steep, two-lane roads near his home in Yosemite West.

Down in the garage, Caldwell and Sjong discuss the protection they'll use on the near-crackless chimneys. They want to have adequate free protection that won't significantly alter Magic Mushroom.

Adequate usually means placing a piece every body length or so, given that any fall will involve plummeting twice the distance from the piece below you. The chimneys are an airy place, where the climbers are enclosed in a granite fold that opens into the void. As they're learning on the wall, the “runouts” the distance between each piece of protection will sometimes require them to climb 15-foot stretches between tiny cams.

The chimneys are subtle features requiring a contortionist's grab bag of nightmare tricks: blind, behind-the-head, straight-armed presses that morph into wide stems; painful knee bars, in which the lower quadriceps is cammed against the rock; heel-palm opposition, in which both feet are kept, toes down, on one wall while the palms are extended as if in supplication. Sjong says he'll wear only cotton on the climb, since it snags well on the granite, providing extra friction.

“What are we missing?” Caldwell asks. He's pillaged the gear reservoirs behind the garage wall, emerging with highly specialized pitons that they'll hammer into the chimneys. On the floor sit ten Peckers of various sizes wafer-thin, beak-shaped pins that fit into hairline seams. Caldwell has also pulled out a dozen-odd Bugaboos and Knifeblades (flat-bladed pitons with forged, offset eyes, also for use in tiny cracks); seven angles (traditional, spear-shaped pitons, for slightly wider cracks); two Realized Ultimate Reality Pitons (square mini-hatchets, half the size of a credit card); a debolting tool essentially a re-milled piton resembling a tuning fork, for removing unreliable old bolts; a hand drill, two bits, and a blow tube for clearing rock dust from the bolt holes; and six bolts and hangers, to use in place of removed hardware.

They look over the spread. Caldwell jokes that it would be much easier to aid-climb the thing. “To be fit to free-climb takes a lot of work,” he says. “I mean, you could drink a gallon of wine every night and still aid up El Cap.”

“You're not supposed to do that?” counters Sjong. They both laugh, knowing that the aid climbers' road map is what has allowed them to make these explorations in the first place.

“Those chimneys are going to be scary,” Caldwell continues. Once they hammer a few pitons in the chimneys, the guys figure they can lead the rest of the route on traditional gear the nuts and cams that the leader places and the second removes.

Atop El Cap, the climbers found a partially damaged portaledge, which they put in place below the chimneys, 18 pitches up. They'll spend the next three weeks or so on the wall, eventually trying the hardest pitches on top rope and then on lead. While they're in this worker-bee phase, they'll also ferry supplies down from the summit.

Through a spotting scope, I watch the boys try the route that first week, then head home to Colorado in late April. On May 5, one week before Caldwell and Sjong are to attempt their final push, Caldwell sends me an update.

“Since I last e-mailed, we spent four more days on the route,” he writes. “We figured out the gear, hammering in the required pins, and led most of the hard pitches. It is coming together nicely. I feel like our stamina is increasing and our bodies are adapting to the vertical world. We end the days with more energy, and even our hands are swelling less.” Still, Caldwell says he's worn down his fingernails until they bleed, and Sjong has bruised his coccyx and buttocks shuffling up the bombays.

Caldwell continues: “I was thinking about how the article is about the science of climbing and how we have had to analyze every ripple, every spot of texture. This climb really seems to be about finding the places on the faces that tilt one degree in the right direction and therefore are more solid to stand on. Deciding on the exact position to switch from chimneying to stemming to laybacking .” He winds up by writing that he feels lucky to be climbing at a time when so many El Cap routes remain to be freed.

The next day, Sjong e-mails the gear list. It's three pages, detailing the rack for each block of leads and then giving a pitch-by-pitch breakdown all in all, hundreds of placements. The climbers will head up with this rack, one 9.2-millimeter lead line, and a 5mm “tag” line a thinner auxiliary cord used to pull up a heavier worker line, for any heavy hauling. They've cached food, water, and provisions in a few key spots.

From May 12 through May 16, Sjong and Caldwell live on the wall. On day one, the climbers move smoothly through the first 13 pitches nearly half the route stalling slightly six pitches up, on a 5.13b/c traverse that they haven't practiced enough. They spend the night on Grey Ledges, a small, two-tiered, sleeping-pad-width platform roughly 1,500 feet up. The second day starts with a harsh warm-up: a pitch of 5.13b, where both climbers fall. But they sort it out and make it to the fixed portaledge at pitch 18, below the yawning chimneys. Here they pick up three days' worth of fresh supplies a gallon of water per climber per day, food, Neosporin, sleeping equipment, and warm clothes.

On day three, their pace slows they do only three pitches. Sjong falls four times on his hardest lead, a 5.13d chimney to a rounded layback, before succeeding, and Caldwell falls once on the hardest pitch, a 5.14a, before he makes it. Sjong tries this one for two solid hours, to no avail. (He'll call the pitch his “asterisk,” since he never climbed it continuously without falling, doing it instead in two sections.) He says he and Caldwell didn't get emotional about the holdup it was simply a case of what Sjong calls “the strong getting stronger and the weak getting weaker.”

That afternoon, the climbers set up their sleeping bags as sunscreens over their portaledge, using Sjong's iPod Shuffle to listen to what Caldwell, who's naive about such things, calls “death metal” (Guns N' Roses, Led Zeppelin, Metallica). The next day, they rest, a boring proposition with only the Shuffle for entertainment.

On the fifth day, May 16, the climbers top out, moving surprisingly quickly through the final crux, a 120-foot, 5.13d finger crack called the Seven Seas, which cuts through a double-overhanging apex to a slightly overhanging headwall crack.

And with that they've completed the hardest overall big-wall free climb in the world, tougher even than Dihedral Wall, an El Cap 5.14a a few hundred feet left of Magic Mushroom that Caldwell freed in 2004.

Back at the Caldwells' house later the next day, Sjong jumps into his EuroVan, bound for Boulder. The moment he's gone, Caldwell heads downstairs to train. The two-person climb left him feeling exhilarated, wanting more. It's an energy surge partially explained by what Caldwell calls “the flywheel effect.”

“As you start to really learn El Cap's friction,” he says, “you can climb knowing exactly how much weight to put on your feet without tiring your arms.” Now he knows he can free the entire route in under 24 hours. Magic Mushroom has fresh chalk marks to help point the way, and he knows all the sequences and gear. Still, the line has 11 pitches of 5.12 and 10 of 5.13 to 5.14. Failure is a real possibility.

On May 31 at 5 P.M., Caldwell and Rodden uncoil their rope in the oaks below Magic Mushroom. Rodden stops Caldwell to daub on sunscreen and ask if his knot is good. Caldwell has timed their departure to coincide with three important windows: having enough daylight to complete the 5.13 traverse on pitch six; beginning the stacked pitches of 5.13/14 in the chimneys at first light; and arriving above those, poised for the 5.13d Seven Seas pitch, in concert with El Cap's cooling midday updraft.

The plan is this: Caldwell will lead on a 60-meter, 9.8mm dynamic (stretchy) rope. Atop each pitch, he'll clip the super-8 knot into the anchor; Rodden will then speed-jumar. Once at the anchor, she'll stay tethered to her jumars five feet down, a dynamic setup that keeps her from being yanked abruptly skyward if Caldwell falls while she's belaying.

Caldwell is going superlight. He will rack the gear in order of placement and bring only what he needs; use one-ounce carabiners; and carry Spectra slings, made of featherweight climbing-spec nylon. He'll harness-rack the gear until the chimneys, at which point he'll clip it in to a Spectra sling over his shoulder, to prevent it from rubbing the rock. Rodden will carry a stripped-down backpack stuffed with jackets, top layers, a sausage-and-cheese sandwich, and spare headlamp batteries. The pack also holds Caldwell's “ninja shirt,” a black hoodie that grips the rock well and has brought luck in the past.

Along the route, Caldwell has left four caches in place. The first, at one-third height, contains energy bars, sports-drink mix, a 1.5-liter bottle of water, and supplemental protection. The second, halfway up, holds a gallon of water. The third is at the fixed portaledge, 18 pitches up, where the pair will nap below the chimneys. Here, Caldwell has crammed into a haul bag two sleeping bags and pads, more bars, Power Gel, a Red Bull, a stove, oatmeal, recovery-drink mix, cashews, long underwear, a puffy jacket, a 100-gram bag of climbing chalk, and another gallon of water. He's also stashed a pair of La Sportiva Miura rock shoes, new but slightly broken in. The final cache sits below the 25th pitch: another gallon of water and a Red Bull.

Caldwell estimates that the legwork in the chimneys puts 250 pounds of force on his feet, quickly rendering the shoes soft and imprecise; he wants to start the hardest leads with a fresh pair. He knows he'll have to be bold, climbing quickly and decisively so as not to bog down. But he's a veteran as long as he stays on top of the protection and ropework, even when tired, he won't face any falls longer than 40 or 50 feet.

Rodden is key to the ascent. “She's really good up there she's fast, she knows the systems really well,” Caldwell says. “But, probably more important, she understands what I'm going through physically and emotionally.” Rodden, for her part, knows Caldwell won't buckle or freak. With only one rope between them and no easy retreat, this matters.

“I've never seen Tommy scared on El Cap, nope,” says Rodden, who recalls him once leading two 5.12 pitches in a snowstorm to get them off the wall. “Up there, he's in his element. Ever since he could walk, he's been in the mountains.”

Caldwell will move through the night, headlamp-climbing through one 5.13b crux, the Bird Beak pitch. There, he'll lead the opening 30 feet (the hardest) with only the three pieces he needs, and then, tethered to a small cam, he'll drop a loop of rope to haul up protection for the remainder. Failure has crossed his mind: “I've never done something like this that has this many hard pitches,” he says. “I could just run out of power.”

Which is precisely what happens.

On June 1, 20 hours after starting, Caldwell and Rodden reach the Seven Seas pitch. Caldwell has freed everything thus far, but here, 110 feet off the belay (and 2,600 feet above the ground), he falls three times on the route's last really hard move, a long, technically precise reach to a flake. Rodden spends four cold, cramped hours belaying on this pitch alone. Hanging off his harness back at the belay, Caldwell takes 30-minute naps between attempts. Rodden massages his blasted forearms, which have started seizing after only two moves, forcing his hands open.

Caldwell drinks a Red Bull. Nothing. The climber is exhausted, and the sun's come around, too, blinding him, heating his shoes so they roll unhelpfully, and making his hands sweat. He decides to give up, and the pair jumars to the top, summiting 23 hours and 45 minutes after starting.

Up on the summit, Caldwell doesn't moan or blame the gods. His big toes have gone numb (they'll remain so for weeks), and his hands and feet are so swollen that the small climbing wounds in the flesh (“gobies”) have countersunk. But he's ready for another go.

Six days later, on June 7, Caldwell and Rodden return. Caldwell has gone back midweek, relearning the pitches and reprovisioning. This time, the pair tops out in 20:02. This time, Caldwell leads every pitch free, taking only five falls total, having to redo two 5.13 pitches but not the Seven Seas. No climber anywhere has achieved anything like this.

“From my perspective, Tommy Caldwell's ascent of Magic Mushroom all-free in a day is state of the art, an unimaginable performance of passion, overpowering will, and Olympian talent,” says John Harlin III, editor of The American Alpine Journal. “For 50 years, El Cap has been the granite crucible the world knows what happens here and who does it, because this is the gold standard. And right now the standard-setter is Tommy Caldwell.”

Caldwell says he entered a “super-relaxed” state during the climb, which allowed him to move more quickly and precisely, reaching the pitch-18 portaledge with time enough for a three-hour nap. And he wasn't, he adds, especially pumped on the Seven Seas. Up there, within earshot of Rodden's shouted encouragement, Caldwell snagged the flake to finish the pitch, then raced through a final, 5.13a rope length to the summit slabs.

After crashing out back home, Caldwell had enough energy to return the next day, hike the East Ledges, and take down fixed lines and gear caches. “Which leads me to believe,” he says, “there must be room for more.”

Number Crunching

The A-B-C's (and D's) of rock-climbing.

To rate the difficulty of rock routes, North American climbers use a numerical scale called the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), refined at California's Tahquitz Rock in the 1950s. Roped, technical rock climbing is considered “fifth class” and was originally a closed scale broken down into 5.0 through 5.9. (Steep hiking is second class; highly exposed scrambling that might require a rope is fourth.) When climbs harder than 5.9 emerged circa 1960, the system expanded to include 5.10, and then 5.11 and up through today's 5.15. In addition, 5.10-and-beyond climbs take one of four a, b, c, or d sub-ratings, with d the hardest. Other ratings might be appended for the length of the route and the reliability and spacing of protection.

As you move higher in the YDS, the rock invariably steepens, the holds shrink and grow farther apart, and there are fewer rests. In Yosemite, known for its sheerness, the ratings can also reflect a pitch's overall physicality, if not its hardest move. Here are some seminal Yosemite climbs at each of the higher grades:

5.10 Wheat Thin (5.10c): This 60-foot climb involves continuously laybacking along the edge of a flake, the climber shuffling his hands and walking his feet up, often at waist height with no hand-free rest ledges.

5.11 Butterballs (5.11c): Eighty feet long, this route is dead vertical, with a finger-width (0.75 1.25 inches) fissure splitting a blank face, and some relief in the form of small foot edges. The climber ascends by finger locking: inserting his fingertips, thumb either up or down, and then twisting to complete the grip.

5.12 Tales of Power (5.12b): This thin, 60-foot crack overhangs for 20 feet. It requires a sustained section of butterfly jamming, in which the climber must contrive a hold by making a modified “A-OK” sign, stacking the middle and ring fingers atop the tip of the thumb and inserting this digital wedge. Your feet go in the crack, too, camming with a twist of the ankle.

5.13 Phoenix (5.13a): A past-vertical, 140-foot crack that's conquered via tight hand jams hand inserted into the crack and then flexed, to oppose the fingers and the back of the hand.

5.14 Houdini Pitch, the Nose (5.14a): On this dihedral, you have to press your body against its walls and engage in a 180-degree contortionist's turn, scootching inch-by-inch like you would up the inside corner of a building.