How the World’s Most Difficult Bouldering Problems Get Made

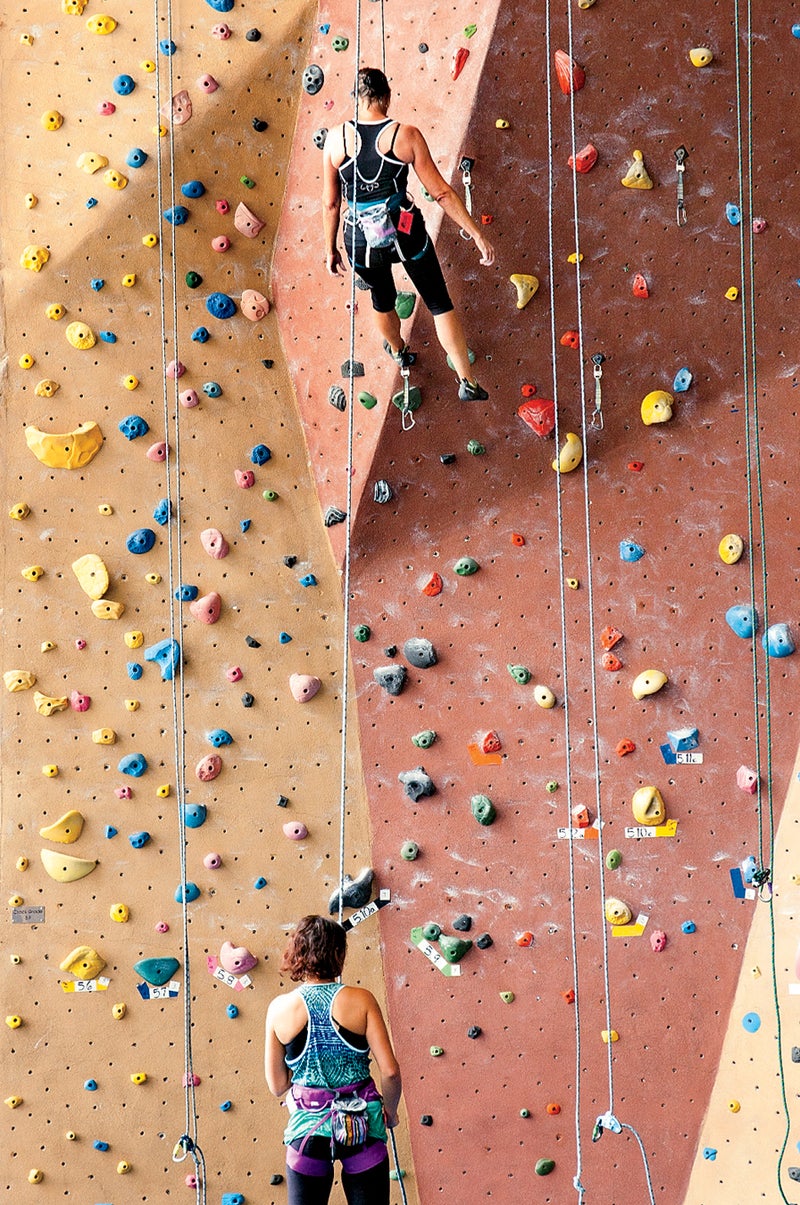

The artificial holds and lines devised for gyms and climbing competitions don't just happen—they're created and placed by devious people who want to force you to stretch, contort, curse, fail, and fall. We go behind the scenes with the masterminds who make this booming sport a serious challenge.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The route setter studied the blank gray surface.

His section—part of an array of climbing walls set up outdoors under a huge tent—was 16 feet tall and 10 feet wide, and it loomed above the chalk-dusted mat at a forward-facing 40-degree angle. His eyes darted from one position to the next, dancing along a grid of bolt holes that were laid out every six inches, like a sheet of graph paper. Strewn around the stage were thousands of Crayon-colored climbing handholds, a wicked assortment of crimps and jugs and pinches and pockets that he would use to fill this void. After a moment of reflection, he unholstered his cordless drill and affixed a bright blue hold to the wall with a whir and a screech. The hold had an intricate, primal-looking pattern etched into it, along with a pocket that could fit (barely) two flexed fingers.

It was a Tuesday in early June, and the setter, Max Zolotukhin, was part of an elite six-man team planning 36 routes, or problems, for the in Vail, Colorado. The best climbers in the sport would be arriving that weekend, including Jan Hojer, the six-foot-one German powerhouse, and Adam Ondra, the Czech bean sprout with sinewy arms and a mop of curly hair. The setters would provide the challenges that would separate their performances.

Bouldering routes are shorter and more intense than roped routes, typically consisting of just five to fifteen moves, which the climber performs to advance from one plastic hold to the next in order to “send” the problem, or complete it. One of the things setters are often asked by passersby is “Where’s the map?”—as if they’re following orders passed down from a board room in Turin, Italy, where the International Federation of Sport Climbing has its headquarters. But the setters are the wizards who really run the show. They are to a climbing wall what coders are to a video game, the geeks who keep you up all night obsessing over that winning sequence.

Route setters are to a climbing wall what coders are to a video game, the geeks who keep you up all night obsessing over that winning sequence.

Zolotukhin, who is 29 and is known as M.Z. to climbers at in San Francisco—his home gym—was the rookie here, and naturally he had the flashiest plans. With a bulky pair of Five Ten sneakers and a Husky tool belt around his waist, he looked like a skateboarder working construction. He is rangy and muscular, with trim sideburns, taped fingers, and a silver hoop through his right ear. Whether it was his freshness on the competition circuit, the scope of his ambition as a setter, or a more general quality of his meticulous character, he had come to Vail on a mission.

“I do a lot of my thinking on planes and other places where I don’t have Internet access,” he told me as a gondola hummed up the grassy ski slope next to the stage. He showed me an iPhone spreadsheet in which he had broken down each of the eight wall bays he might get assigned and described which problems he might set, using jargon-laced shorthand.

“Inside flag dual tex half moons; volume under angle change bay 1,” he wrote beneath one entry, referring to a sequence that would force climbers to counterbalance themselves using the foot closest to the wall.

“Super dorky,” he said of his notes. “No one does that.”

The problem Zolotukhin was setting just now was a big deal: the last climb in the men’s final. He stepped up to the wall and dangled from the pocket with the ring finger and middle finger of his left hand. Then he reached up with his right hand and wrapped his fingers around his wrist. His goal was to force the athletes to hoist themselves up to the next hold using this pull-up move, which is called a handcuff. In the next move, they would have to spin 360 degrees to reach a third hold with their left hand.

“People will figure that out?” I asked.

“If you don’t give them any other options,” he said.

Last year, , 29 new indoor climbing gyms opened in the U.S.—bringing the total nationwide to roughly 365—which helps explain why route setting is now a viable alternative to a life of dirtbaggery. The sport has taken off even in Midwestern cities where the nearest rock is a meteorite in a cornfield. Today, head setters at top gyms earn salaries of $70,000 or more, fly across the country to guest-set at other gyms, and work national and international competitions.

“The best thing happening now is that route setters are getting their due,” says Chris Warner, owner of , which operates four gyms in Maryland and Colorado.

As recreational rock climbing gained popularity in the early 20th century, artificial walls were little more than a way for climbers and alpinists to train during the off-season. In the late 1930s, Clark Schurman, chief summit guide on Mount Rainier, built a 25-foot practice wall out of granite boulders and troweled concrete in west Seattle that still stands today. One of the first indoor climbing walls in the world, erected alongside a squash court at the University of Leeds in 1964, featured natural rocks cemented onto brick, along with hand-jamming cracks carved into mortar. The designer, Donald Robinson, now 88, had grown weary of watching climbers spend all winter in the pub and then injure themselves outside the moment Easter rolled around. “In those days, they wouldn’t go to the gym,” Robinson says. “That was for the common herd.”

Though popular, these early walls had a major downside: you couldn’t change the rocks. In 1985, François Savigny, a French engineer and rock climber, founded the company and began selling the first bolt-on climbing holds made of polyester resin. Later the industry shifted to less toxic and more durable polyurethane—the stuff used to make Rollerblade wheels. Rather than reproducing inward-facing contours and fissures of an eroded cliff face, these holds could be endlessly rearranged on a flat wall. It took a while for modern holds to migrate to the United States. Seattle-based Vertical World, which bills itself as the first commercial climbing gym in the country, opened in 1987. Back then people were still gluing rocks onto cinder blocks.

Even in the late eighties, gym climbing was mainly something you did when you couldn’t get to the crag. A couple of teenagers working the front desk might bolt a bunch of holds to the walls, but it was left to the climbers to devise the routes. Route setting emerged as a professional pursuit in the 1990s, and it took off creatively in step with bouldering’s increased popularity.

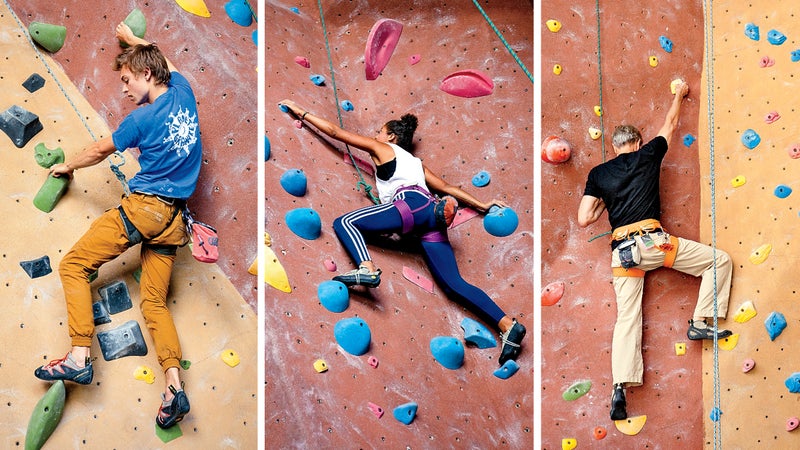

Which only makes sense. In bouldering the goal is not about attaining the summit along a particular set of pitches, but to use specific body movements to progress through a prescribed sequence of holds along both horizontal and vertical axes. Bouldering opened up people’s minds about what was possible on a climbing wall. It made all climbing more precise, more mental.

In a typical gym today, setters mark specific routes with colored tape—or matching holds—to which they assign difficulty ratings. Bouldering problems are graded on the V scale, from the ladder-like cake walk of a VB (beginner) up to a V16, which requires gecko fingerwork and gravity-defying leaps known as dynos. Roped climbing routes go from the easy 5.0 to the nearly impossible 5.15c.

By the early 2000s, climbing walls had become the canvas for fleeting pieces of functional art. Routes need to stay up long enough for climbers to solve them and pump a fist at the top, but not so long that they become routine. Some routes are so obvious, they can seem as dull as pulling on a rowing machine. Others have a magical flow built in, and you land back on the mat with a buzz.

“In some ways, climbing outdoors is stifling and boring, because you are limited by nature,” says Mike Helt, an instructor for the . “In here we are not limited by anything other than technology and the human imagination.”

In Vail, Zolotukhin was beholden to a pair of experienced silverbacks on duty: the chief route setter, Percy Bishton, a boyish 43-year-old Brit with tousled gray hair, and Chris Danielson, 38, a renowned American whose russet beard was feathered with white streaks. Between the two of them, they had more than 40 years of experience bolting pieces of plastic onto walls. “I’m retired after this one,” said Bishton, who opened one of the UK’s premier climbing gyms, Sheffield-based , in 2006.

On Tuesday morning, Bishton called the crew over to review problems for the final. One setter had been inspired to mimic a wild swing from Jungle Book, a famous climb at a bouldering spot in southern Illinois called Holy Boulders, but it had evolved into something else. Zolotukhin, meanwhile, had set a problem he called Princess of Persia, which was modeled after a 1980s computer game featuring a hero leaping across spike-filled chasms and scaling vertical walls. Bishton liked that one. “It’s very ambiguous,” he said. “You can’t really see how to do it.”

Setting for a competition is a little different from setting in a gym. During the World Cup stop in Vail—an annual cash-awarding mini-tour for men and women held in various cities in Europe, North America, and Asia—the athletes are given brief, varying amounts of time to look at and attempt climbing problems. In the most difficult challenges of the event, the setters wanted to do more than just test the competitors’ forearm muscles; that’s a recipe for a tie, because all these athletes are ripped. Rather, they wanted to create a men’s problem in the realm of V10 or V11, but one that was inscrutable enough that there would be a few successes (“tops”), a few falls, and one hell of a show.

A large gym may stock 40,000 climbing holds, and when a new shipment arrives, setters will hide the ones they want to use first.

As they reviewed the next climb, Danielson was casting about with a devious look on his face. “What are you seeing?” Bishton asked.

“I feel like it’s too hard,” Danielson responded. From a plastic tub onstage, he pulled out a wormy red, white, and blue hold about the length of his arm and covered in warty-looking bumps.

“A big knobbly cock!” Bishton joked. “Where do you want to put it?” Danielson held it up between two bulbous gray holds. The combination looked like a diagram from a medical textbook.

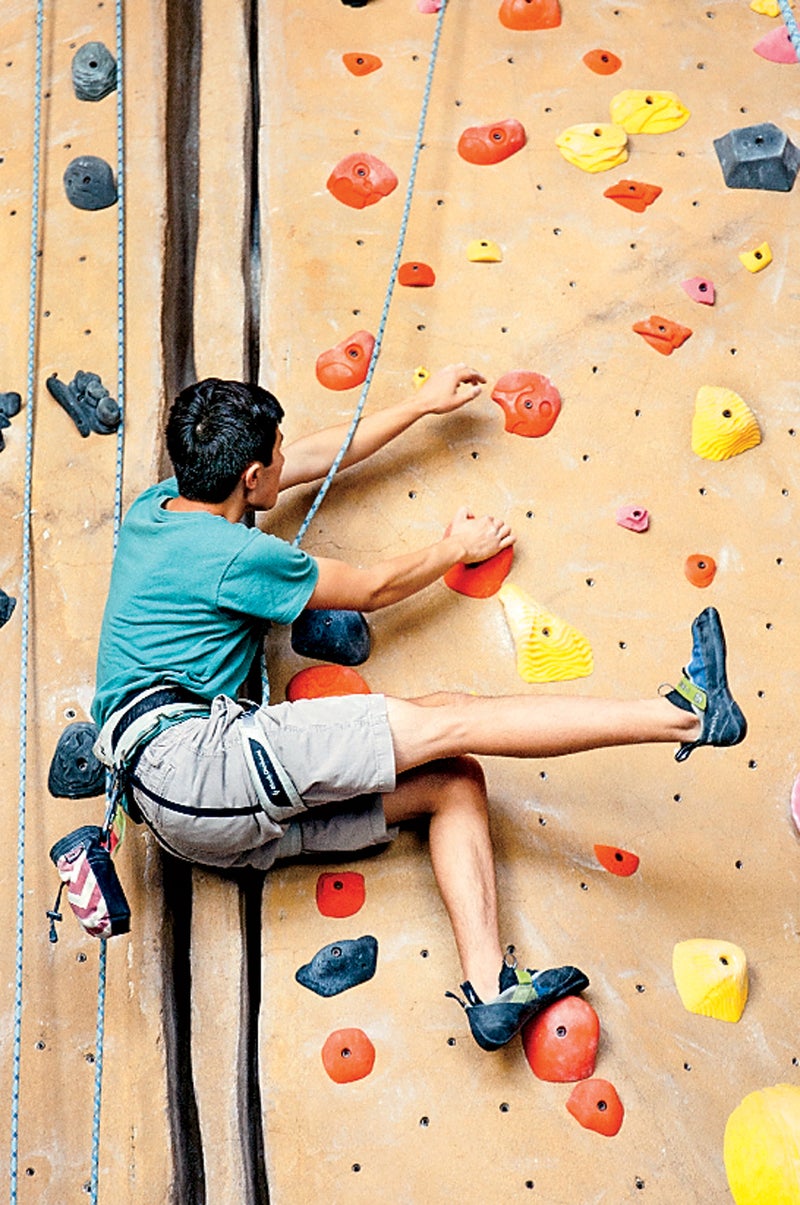

By then, Zolotukhin was free to focus on the handcuff boulder—the only final problem that hadn’t been set. After screwing the pocket onto the wall where he wanted it, he worked backward to the starting holds. He needed them to be far enough to the right so that the climbers would have to let their legs dangle and ascend using only their arms, called campusing. At the same time, the pocket couldn’t be so far away that shorter climbers would be at a disadvantage.

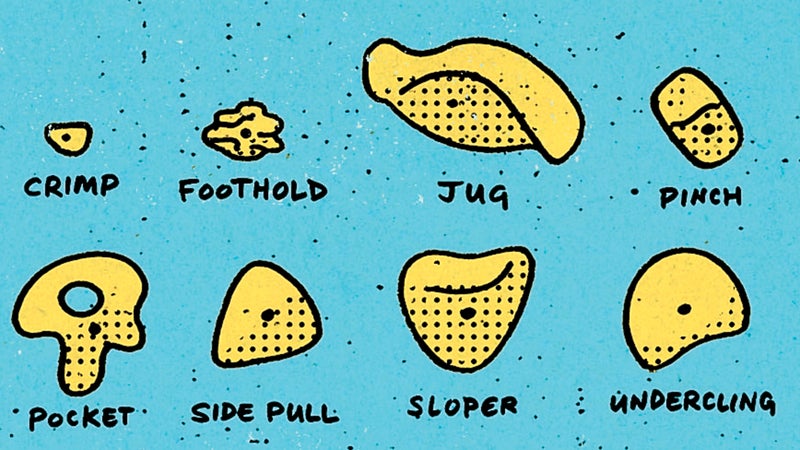

If you think about a climb as a sentence and each move as a word, the holds are individual letters. The most commonly used holds provide a horizontal edge that you can hang from. When the hold is extremely positive, which means it has a large lip or is otherwise easy to grab, climbers call it a jug. A crimp, by contrast, has an edge that’s so thin, you can fit only your fingertips on it. When that edge is oriented vertically and off to the side, it serves as a side pull. Closer in it’s a Gaston, which the climber pulls on with elbow bent, as if prying the lid off a coffee can. If the edge points toward the ground, then it’s an undercling, and the climber must pull up and out to stay on the wall.

Pockets can be deep or shallow and can restrict you to using three, two, or even one finger. Pinches require you to squeeze the hold with the help of your thumb. Then there are slopers, which are smooth and round and might be used with an open-handed grip to maximize friction or for a mantle move, in which the climber pushes against, rather than pulls on, the hold. Some are designed only for a foot, with a surface just large enough to accommodate a single toe. Sometimes there’s no foothold at all, in which case climbers must smear a foot against the blank wall, relying on the sticky rubber of their shoes. Finally, large holds, called volumes or features, alter the geometry of the wall and can be modified by screwing smaller holds, known as jibs, onto their surfaces.

Holds come in an immense variety of shapes, sizes, and textures. One of the larger manufacturers, Colorado-based , sells more than two dozen styles, and most lines have somewhere between five and twenty different crimps. A large gym like Earth Treks may stock 40,000 holds, and when a new shipment arrives, setters will hide the ones they want to use first. Louie Anderson, a prolific Southern California shaper who has been designing holds since the dawn of the gym era, creates 1,000 new shapes every year. The designs have changed a lot from the early days, when holds were cast in earth tones and mimicked rock features. Today they’re more artistic, colorful, and ergonomic, so that a day in the gym won’t tear off your hard-earned calluses. The Missouri-based climbing company So Ill produces fluorescent green holds .

Zolotukhin has a freakish handle on this diversity and can sort through the buckets of near identical crimps with ease. With each new hold in Vail, he moved up his ladder and completed a first draft of the sentence that stretched from the bottom of the wall to the top. Setters call this the skeleton.

At the end of the day, as a yellow slash of sunlight cut across the climbing wall, Garrett Gregor, a.k.a the Machine—a climber with a V-shaped torso—pumped himself up to test how Zolotukhin’s route worked in practice, which is called forerunning. In this instance, the Machine pushed past the crux of the climb without having to do the handcuff or the hoped-for 360. In setter speak, he had “broken the beta.”

Zolotukhin looked deflated. Sometimes it’s fine for a problem to have several solutions, as long as they’re as difficult as the intended one. In this case, what the Machine did defeated the entire purpose of the climb.

Zolotukhin and Danielson conferred about ways to make the handcuff mandatory. “It’s really hard to compel people to want to do that,” Danielson said. They had changed the pocket out several times, varying its depth and size, and had talked about ways to modify it with Bondo, the commercial putty used in car-body repairs. “If you make the pocket very good, you don’t need that,” Danielson said, referring to the handcuff move. “If you make the pocket very bad, you may handcuff but not be able to pull through.”

Manuel Hassler, a Swiss setter with Albert Einstein hair, suggested adding a second pocket high on the wall. This would bump the handcuff up and make the sequencing more pronounced: left hand in the lower pocket, right hand in the upper pocket, then spin around and grab a crimp with the left hand. Danielson liked the idea, but Zolotukhin was hesitant. “We can’t make the whole problem a jungle gym,” he said.

“I don’t disagree. I’m just living in compromise-land,” Danielson said.

“It would be really nice to get this to be a beautiful thing,” Bishton said.

The Machine pushed past the crux of the climb without having to do the handcuff or the hoped-for 360. In setter speak, he had “broken the beta.”

“The debate now is, you put a pocket here, you just jump to the pocket. Pocket. Pocket. Swinging around,” Danielson said. “The crowd loves it, but it’s not that interesting.”

Bishton pointed at a large undercling on the right. “For sure, the jug is coming off,” he said, pointing to a large hold he wanted to replace with something smaller and more difficult.

This put Zolotukhin on the defensive. “Some of the best photos happen in comps when you are on a jug,” he countered.

“I don’t like the jug in the middle of the route,” Bishton said. “Then you get the fist pump of glory before they send it.”

, which hasn’t been updated for a couple of years, features videos of him and his buddies hooting while sending problems like Wet Dream, a V12 in Black Velvet Canyon, Nevada. On the same page, you can find a short manifesto in which he subscribes to Ayn Rand’s view of man as a “heroic being.” Online he comes across as earnest, slightly pompous, and far less self-effacing than he is in person. “I want to be the best route setter in the country and I want people to know it,” he writes. “Not for the sake of my little ego, but because I believe that productive achievement is man’s noblest activity and I want to be judged by mine.”

Zolotukhin was born near Kiev, Ukraine, and grew up in Gainesville, Florida, where he taped out his first route, at age 14, on his first day climbing. He raced through a dual degree in psychology and political science at the University of Florida in three years, in order to devote himself full-time to bouldering. At first he wanted to be a pro climber. In 2009, he took 16th at the American Bouldering Series (ABS) National Championships and competed at the World Cup.

Zolotukhin was feeling invincible that summer when he tried to boulder Supernova, a 5.14b sport climb in Rumney, New Hampshire, with only crash pads and spotters as protection. “I hit the pocket accurately but for reasons unknown, my body sagged out and I helicoptered off,” he wrote later on a blog. He fell more than 20 feet, missed the pads, and fractured his talus on a jagged boulder. His friends carried him down to an ambulance.

“It was a really dumb thing to try to do,” he told me. He flew back to Florida and spent the next two and a half months on his mother’s couch. About a week after the accident, he was doing pull-ups and using a hang board to maintain his finger strength. After five weeks, he began bouldering easy routes with a plastic walking boot on his ankle. He was obviously a gifted athlete, but he realized he would never be an Alex Honnold or Kevin Jorgeson. As he reined in his daredevil instincts, setting became his outlet.

“I don’t have exactly what those guys have, but I have something else that is equally valuable, and that is a creative mind,” he says. “In the end, I still have an awesome climbing career, and I love it just as much.”

In August 2011, Zolotukhin moved to California to take a full-time position at Planet Granite, which has three gyms in the Bay Area and one in Portland, Oregon. As setting has become professionalized, getting certified for competitions is like earning one’s stripes as a master welder.

After attending a clinic run by USA Climbing, he completed an internship under Danielson during the Unified Bouldering Championship in New York City in 2011, and, later, an apprenticeship in Atlanta under Mike Helt. By 2013, he had earned the rank of assistant route setter and was invited to set at the ABS Nationals. Finally, he was awarded the coveted slot at Vail, his first event on the world stage.

On Saturday afternoon, black curtains hung in front of the climbing wall, concealing it from the crowd gathering on the grassy lawn. Zolotukhin, Danielson, and the other setters were wobbling on their ladders. I saw Bishton scowling at the edge of the stage like a true Englishman. “It’s bullshit,” he told a friend. “It’s a waste of a boulder!”

He was ticked off because he hadn’t had a chance to finalize one of his problems before Danielson took it down on Tuesday. The start featured five blue triangles, which gave the male finalists a platform from which to lunge toward a massively awkward, bubble-shaped volume to the left. Then the climber would have to make his way up the arête, or the edge of the wall, to the top, where he’d have to reach a second bubble. A series of tiny holds dotted the wall like a trail of bird droppings. These were footholds.

“What’s with all the feet?” Bishton asked.

“I haven’t decided yet,” Danielson said.

“Fucking hell, Christopher!” he scoffed. “It doesn’t look very hard.” Bishton left him alone, and Danielson kept tooling away. Then he took a front-row seat to watch the show.

Adam Ondra , the third problem of the final, then he spidered up to the middle of the wall with little effort. Clinging to a triangle, he stuck his foot out and leaped for the final bubble. His big hands caught it, but he slid off backward with such momentum that he tumbled from the mat and landed at the feet of two judges. The crowd gasped.

Danielson was smirking like a demented leprechaun. “You liked that?” I asked him. “I liked that,” he said. We watched as Ondra crashed two more times and, finally, slammed his fist on the mat in frustration.

The last problem of the day, Zolotukhin’s, was up next. Canadian Jason Holowach and mimed his moves. He dug into the first pocket with his left hand and then grabbed the next pocket with his right before stalling out. Off to his right was a wok-shaped volume with a crimp on its far surface, but he couldn’t figure out how to grasp it and dropped to the mat. On his second attempt, Holowach switched his sequence, grabbing the lower pocket with his right hand and the upper pocket with his left. Now his right hand was free to grab the crimp on the wok.

I was next to Zolotukhin, who was hunched over with a deadpan expression on his face. His plans seemed like a bust. “His sequence gets to the bonus,” he said, “but it doesn’t get you to the top.” As if following a script, Holowach fell off the wall and failed to complete the problem as the clock wound down.

, a clean-cut 18-year-old from Utah, who had been dominating all day. He seemed to be reading Zolotukhin’s beta, taking the low pocket with his left hand and the high pocket with his right. After a moment, he was hanging from his right hand alone and his body naturally pivoted clockwise, away from the wall. He was now facing the crowd, hanging under the lip of the wall.

That’s when it happened. The teenager handcuffed his right wrist and pulled himself up until his biceps bulged and his arm was bent at a 90-degree angle. Then he lunged for the crimp and pinched it securely with his left hand. The crowd roared, and Zolotukhin slapped a palm on the stage.

Coleman kept ascending to the final hold, mugged for the camera, and pumped his fist. Next to us, a cameraman pulled his gaze away from the viewfinder and looked over at the proud route setter. “Is that what you meant to happen?” he asked.

The setter nodded. “Yeah,” he said coolly.

“Fuck,” the cameraman said.

Brendan Borrell (@) wrote about French ���ϳԹ���r François Guenot in June.