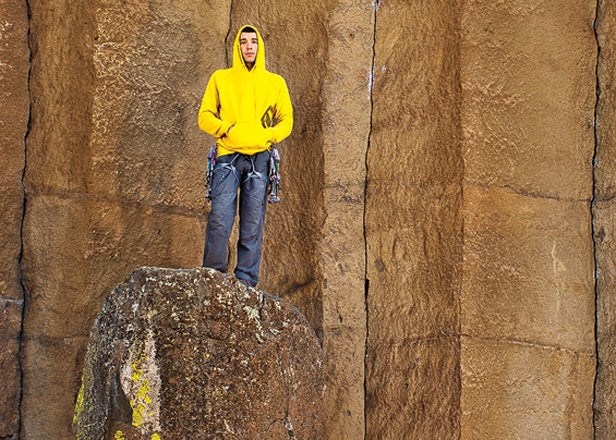

Alex Honnold, No Strings Attached

At 25, climber Alex Honnold is already the undisputed master of the most dangerous sport around; scaling iconic rock walls without any ropes. Is he the next great thing in modern climbing? Or a suicide mission in sticky shoes?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

After a little more than two hours of climbing, Alex Honnold reached Thank God Ledge. He was nine-tenths of the way up the northwest face of Half DomeÔÇöthe nearly vertical 2,000-foot granite wall that towers above Yosemite Valley. The ledge, a 35-foot-long ramp that varies in width from five to twelve inches, forms a blessed respite from the esca┬şlating severities of the face. By hand-traversing leftÔÇöfacing the wall, fingers jammed in the crack at the back of the ledge, feet plastered against the rock just belowÔÇöclimbers circumvent the utterly blank cliff above.

Twenty-three years old that day in September 2008, with a lanky five-foot-eleven build, big brown eyes, and prominent ears, Honnold was on the verge of pulling off an unprecedented feat. He had no rope and no nuts or camming devices to jam into cracks to catch him if he fell. He had no carabiners to clip into the bolts that protected the hardest moves on the climb. He had no partner. He wore only a light shirt and shorts and carried nothing but a flask of water, a few energy bars, and a chalk bag dangling from his waist. He was practicing the most extreme and dangerous form of rock climbing. It's called free soloing, and its fundamental rule is stern and simple: If you slip, you die. Before that day, no one had free-soloed a route in North America as long or as difficult as the northwest face of Half Dome.

No one witnessed the climb, and Honnold had told only two friends of his plans. Below him stretched 1,800 feet of sheer granite; above, the last 200 feet of the wall. Downclimbing the route was out of the question.

Caldwell expresses his concern more succinctly. “I really like Alex,” he says. “I don't want him to die.”

Once he reached the ledge, however, Honnold decided not to hand-traverse but to cross on his feet, with his back to the wall. In his mind, that was the purest of styles. “It was a matter of pride,” he'd later write in an unpublished essay on the climb. Delicately, he put all his weight on one foothold, pushed down on the ledge with his palms, stood up, turned around, and faced out. The wall at his back overhung by a few degrees, threatening to push him off balance.

“The first few steps were completely normal,” Honnold wrote, “as if I was walking on a narrow sidewalk in the sky. But once it narrowed I found myself inching along with my body glued to the wall, shuffling my feet and maintaining perfect posture. I could have looked down and seen my pack sitting at the base of the route, but it would have pitched me headfirst off the wall.”

The key to maintaining the cool it takes to free-solo a sheer face 750 feet taller than the Empire State Building is what Honnold refers to as his “mental armor.” But a few minutes after traversing Thank God Ledge and turning back to face the wall, his feet planted on small sloping holds, his fingers clinging to minuscule wrinkles in the rock, Honnold ran out of armor. It was a novel and disquieting experience. He froze, reeling with existential questions: What am I doing? Why am I here?

The first wave of freak-out seized him. And as Honnold knew full well, “The minute you freak out, you're screwed.”

Honnold displayed an affinity for risk at a young age. When he was five, his mother, Dierdre Wolownick, a French professor at in Sacramento, California, took him to a climbing gym in nearby Davis. “I was talking to the supervisor, and I turned around,” Wolownick remembers. “There was Alex, 30 feet up. I was scared to death he'd kill himself.”

When Honnold was ten, his father, Charles Honnold, an ESL teacher, started accompanying the hyperactive kid to a Sacramento climbing gym. “Dad was never a real climber,” Honnold says. “He was mainly there to belay me. I think he was relieved when I started biking to the gym on my own.”

But Honnold didn't wholly throw himself into climbing until after high school. He had other interestsÔÇönamely, books. “I crushed high school,” he says matter-of-factly. “I was a huge dork.” After graduating with straight A's in 2003, he enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, where he planned to study engineering. But that didn't pan outÔÇöthe second semester, he simply stopped going to class. “I just didn't like college,” he says. “On a typical day, I'd buy a loaf of bread and go out to Indian Rock”ÔÇöa small rhyolite outcrop in the suburban Berkeley hillsÔÇö”and do laps.”

In July 2004, 18-year-old Honnold competed in the Youth Nationals, an indoor contest for the country's top 300 teenage climbers. He finished second, winning a spot in the in Scotland that September. But before the competition, things changed. On July 18, 2004, Alex's father died of a heart attack at the airport in Phoenix. He was 55. Charles and Dierdre had recently divorced, an event both Alex and his older sister, Stasia, now 27, saw coming. “My parents waited until I graduated high school to get divorced,” says Alex.

Still, the death of his fatherÔÇöwhom Honnold describes as a “great dad” but a “quiet and private man”ÔÇöwas difficult. “I was kind of depressed,” says Honnold. “I didn't want to do anything except climb.”

He went to Scotland and turned in a lackluster performance, finishing 39th. When he got home, he decided not to return to Berkeley. Instead, his mother lent him her Chevy minivan. Honnold threw a sleeping bag, some clothes, and his climbing gear in the back and hit the road. He's been on the move ever since.

That first summer, he traveled throughout California, living off interest from his father's life-insurance bonds. At , a friendly crag near Lake Tahoe, Honnold completed his first ropeless solo on a two-pitch, 5.3 route. (In the U.S., rock climbs are rated on a decimal scale ranging from 5.1 to 5.15, with the grades above 5.9 subdivided into four classes, “a” through “d.” A 5.3 is child's play.)

According to Honnold, he continued free soloing for practical reasons. “I didn't have any partners,” he says. “I was too shy to meet strangers and too intimidated to talk to 'real' climbers. At first I had no real gift for it. I just did a lot of soloing and slowly got better.”

For the next two years, Honnold traveled and climbed from Nevada to Utah to British Columbia. Then, in September 2007, he showed up in Yosemite Valley and free-soloed two long 5.11c routes, Astroman and the Rostrum, in one day. It was a feat that had been accomplished only once before, in 1987, by the great Canadian free soloist .

Alex was very polite, very safety conscious. Now he's more likely to badmouth you. About a year ago, I was trying to lead this pitch, and I kept falling off. Alex said, 'Dude, what's your fucking problem?

In April 2008, Honnold upped the ante by free-soloing , a 5.12d route in Utah's Zion National Park. Honnold scaled the 1,200-foot sandstone wall in just 83 minutes, inspiring an electric buzz on climbing websites. (Sample posts from the site : “Holy living f#ck!” “I get the Elvis just thinking about it.”) Five months later, he tackled Half Dome. Honnold was suddenly the talk of the climbing world.

Soon, sponsors came flocking: La Sportiva, Clif Bar, New England Ropes, Black Diamond, and The North Face. Honnold says he now makes enough sponsorship money “to support my climbing and save a little bit.” He's also used some of the cash to upgrade his current vehicle, a 2002 Ford Econoline minivan that he lives in, with industrial carpeting, insulation, and a two-burner Coleman stove. “It used to be way more ghetto,” he says proudly.

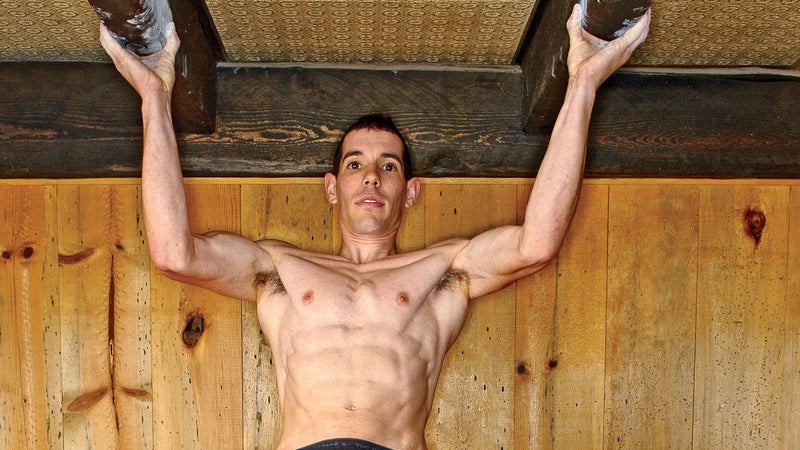

Thanks to his relationship with The North Face, Honnold also gained entr├ęe into climbing's elite, becoming both prot├ęg├ę and partner to the likes of Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin, and Mark Synnott. Anker, who is one of Honnold's heroes, puts the young free soloist's accomplishments in perspective. “Twenty years ago, guys like John Bachar and Peter Croft could climb 5.12, and they regularly soloed 5.10,” Anker told me last October. “Alex can climb 5.14, and he's soloing 5.12. He's fundamentally raised the bar.”

If Honnold has a peer, it's Dean Potter, the brash 39-year-old climber best known for his big-wall solos and BASE jumps with a wingsuit. Potter also invented a practice he calls freeBASEingÔÇöfree-soloing with a parachute that he can open and use to float to the ground after falling off. Recently, there's been speculation that Potter and Honnold both hope to free-solo Yosemite's El Capitan, which is 1,000 feet taller than Half Dome and technically much harder.

Such chatter irritates Potter. “Let's talk about it after it's happened,” he says. “The magazines want a race, but this would go beyond athletic achievement. For me, this would be at the highest level of my spirituality.”

Though he's denied it in the past, Honnold acknowledges to me that he's considered free-soloing El Capitan. He's even pinpointed the route that would be the most logicalÔÇöFree Rider, which has been climbed with a rope at 5.12d. “You'd have to really want it,” he says. “The hardest thing would be just getting off the ground. I kind of want to do it. It would be amazing.”

ÔÇőHonnold, now 25, will be the first to admit that free soloing doesn't push the limits of technical-climbing difficulty. Nothing he does is as physically challenging as the short 5.15 routes that the sport-climbing master Chris Sharma works on for days on end. And Honnold himself routinely performs feats with ropes that are more demanding than, say, his solo ascent of Half Dome. Within the past three years, Honnold has set new world standards in the art of big-wall “linkups”ÔÇöhigh-speed ascents of more than one 2,000-foot-plus cliff in a single day. He's also a terrific route finder: in April 2009, he spearheaded a first ascent on Borneo's 13,435-foot Mount Kinabalu, with Synnott, Chin, and Anker seconding his hardest pitches.

But Honnold's fame is due to free soloing. What makes the sport so mind-boggling is the obvious consequence of the smallest error. And not everyone can simply turn off his or her fear of falling. According to Anker, “I know I can do a route I've done ten times before, but I'd never try it without a rope. There'd be too much interior noise.”

Another of Honnold's heroes is Tommy Caldwell, 32, a leading big-wall free climber. Free climbing is different from free soloing in that it involves a rope and protection: Caldwell relies on a partner's belay as he works pitch after pitch until he can string together a continuous ascent of a long route with no “aiding,” or resting on gear. There is no climber alive whom Honnold admires more. Yet Caldwell echoes Anker's conservatism. “I've never tried to free-solo anything really grand,” he says. “I've fallen completely unexpectedly lots of timesÔÇömaybe a dozenÔÇöon relatively easy terrain, when a hold broke off or the rubber peeled off the sole of my shoe or something. If I'd been soloing, I'd have died.”

The numbers support Caldwell's position. The list of athletes who've pushed the limits of free soloing in North America in the past 40 years centers on nine people: Henry Barber, Derek Hersey, John Bachar, Dan Osman, Charlie Fowler, Michael Reardon, Steph Davis, Croft, and Potter. Five of them are dead.

Hersey fell trying to free-solo the route in Yosemite in 1993. Osman, who also practiced “rope jumping”ÔÇöleaping off walls while attached to nylon cordsÔÇödied in 1998 when one of his ropes broke. A 2006 avalanche in western China killed Fowler, one of the few soloists to embrace high-altitude mountaineering. Reardon was swept off an Irish sea cliff by a rogue wave in 2007 as he free-soloed for a photographer. In 2009, Bachar fell while climbing a route he had free-soloed many times before, on a cliff near his home in Mammoth Lakes, California.

So why would anybody want to become a free soloist? Honnold finds the purity of the craft addictive. “I like the simplicity of soloing,” he says. “You've got no gear, no partner. You never climb better than when you free-solo.” He also finds that the sport fits his psychological makeup. “If I have any gift, it's a mental one,” he says. “Keeping it together.”

But how long can a person keep it together? Bloggers who've never met Honnold have pleaded with him to stop. Last March, Ed Drummond, a British climber and self-appointed pundit of the sport, posted “An Open Telegram to Alex Honnold” on . Drummond had heard a rumor (unfounded, it turned out) that Honnold planned to attempt to free-solo El Capitan's Nose route. He wrote:

Dear Alex,

Stop! Stop right now! While there's still a chance you might live to tell how you nearly fell for it … 3,000 feet more or less down the Nose route of El Capitan, bouncing and screaming for five seconds until you explode, hitting the earth at over a hundred miles an hour, beheaded at the feet of the waiting paparazzi.

When I ask Honnold about Drummond, he says, “If he's a big douche and feels like preaching, well, OK. But he should tell himself not to post that shit on the Internet.”

If Honnold spends a lot of time worrying about his fate, he doesn't show it. Last May at in Telluride, an annual festival, a 12-year-old boy in the audience asked Honnold: “Aren't you afraid you're gonna die?”

Honnold shrugged. “Hey, we've all gotta die sometime. You might as well go big.”

The blas├ę attitude concerns his close friends. “I'm worried that he's going to kill himself,” says Chris Weidner, 36, one of Honnold's longtime climbing partners. “I think free soloing is a numbers game. The more you solo, the greater the chance of making a mistake. Alex disagrees. He says, 'Even though I solo a hundred pitches in a month, on each one the chances of falling are almost zero.'”

Caldwell expresses his concern more succinctly. “I really like Alex,” he says. “I don't want him to die.”

Last October, I spent a week with Honnold at , a massif of volcanic stone rising out of central Oregon farmland. Honnold wanted to visit Smith, the site of the first 5.14 ever climbed in the United States, before leaving on a four-month tour of Chad, Israel, Jordan, Turkey, and Greece.

We met in Portland and drove southeast, me in a rental, Honnold in the Econoline, which is clean and well organized. When we stopped at a motel, I asked if I could pose a few questions. “Sure,” he said. “Might as well get the media B.S. out of the way.”

I did a double take. “Don't take it personally,” he continued. “Going to Virginia next week for The North Face to do a dog-and-pony show. Banff”ÔÇöthe annual adventure-film festival where Honnold was scheduled to speakÔÇö”will be full-on B.S. It's fun sometimes, but it's annoying. It takes away from actual climbing.”

Honnold seems to have no self-censoring mechanism. He often speaks in short, pat locutions, and some of his one-liners can be abrasive. “There's only a handful of chicks in the world who can climb big walls on my level,” he told me. And: “I took a test once; they said I was a genius.” He recently erased himself from Facebook. “It was too crazy,” he says. “I was getting 20 friend requests a day. Some kid would ask, 'Hey, what kind of chalk bag should I buy?' You hate to blow him off, but, like, you don't give a shit.”

Some friends think fame has taken a toll on Honnold. Weidner, his climbing partner, says, “When we started climbing together, Alex was very polite, very safety conscious. Now he's more likely to badmouth you. About a year ago, I was trying to lead this pitch, and I kept falling off. Alex said, 'Dude, what's your fucking problem? It's only 5.13.' He may have been joshing, but it hurt my feelings. He's got a certain attitude now, like unless you're a world-class climber, you suck.”

But Honnold is equally unsparing with himself. When I asked if anyone had approached him about writing a book, he said, “Why? I haven't done anything yet.” At another point he claimed, “I'm a lot mellower than Tommy Caldwell. Which is why I'm not as good.”

I wonder if there isn't something of an enfant terrible in HonnoldÔÇöthe smart-ass kid who blurts out put-downs and boasts just to provoke a reaction. Or Honnold may simply be naive. I pointed out that calling the Banff Mountain Film Festival “full-on B.S.” in print might not go down well with the event's organizers. He shrugged. “I'm sure at some point what I say will bite me in the ass,” he said, “and then I'll stop talking to people.”

Once we reached Smith Rock, however, another side of Honnold emerged. We'd wake at sunrise and eat breakfast cooked on his stove. He'd have a four-egg omelet with bacon, onion, and cheese. He doesn't drink coffee, which he likens to “battery acid,” or wine, which tastes like “rancid grape juice,” or, for that matter, any kind of alcohol. “I smelled Scotch once,” he says. “I thought, 'I should be cleaning my sink with this stuff.'”

After eating, we'd stroll to the base of the cliff. On the way, I twice heard strangers whispering, “That's Alex Honnold. He soloed Half Dome.” At a diner where we ate most evenings, men asked for his autograph or to pose with them for a snapshot. Honnold treated his fans with unfailing courtesy.

On our fifth day, Honnold's girlfriend, Stacey Pearson, a 25-year-old nurse and distance runner from Cleveland, came to visit. She introduced herself to Honnold over Facebook, back when he kept a page. Despite a few rough patches at the outset of the relationshipÔÇö”I had trouble adjusting to sleeping in Alex's van,” she saysÔÇöit's obvious that the two share an irreverent sense of humor. When I asked Pearson if she was worried about his soloing, she joked, “I'll say, 'If you die, I can fly to Europe and find the European guy I've always dreamed about.'” Asked about her, Honnold softened. “I can see being with her for a long time,” he said.

I saw a less abrasive side of Honnold elsewhere at Smith Rock, too. One day, he came across a couple in their fifties struggling to climb and descend an easy 5.5 route on Morning Glory Wall. Honnold, recognizing that the man was in danger of rappelling off the end of his rope, quickly offered advice, coaching the man down to the ground, then lavished him with compliments. “You made it,” he said. “Well done!”

Honnold was poised just above Thank God Ledge, his mind racing, his mental armor in pieces.

When I asked him later about this exchange, Honnold said, “They were cool. It's like they'd gone to a marriage counselor who told them to take up an extreme sport. But they were really giving it their best.” According to Weidner, “One quality of Alex's that I admire is that if he sees a climber trying his hardest, even on an easy climb, he respects the guy.”

Honnold's own intensity is Olympian. At Smith he climbed every day until dark, even though he found the rock hard to like. “It's techy, vertical, crimpy, and pretty much shitty,” he said. By “shitty,” he meant that the crag's routes were festooned with pebbles, like cherries in a fruitcake. If you're hanging on one of those pebbles when it pops loose, then, in climber's jargon, you're “off.”

Because of that texture, Honnold decided not to solo. Then, on our third day at the crag, as we loitered below a section of cliff called the Dihedrals, he abruptly stood up and muttered to himself, “You know, I'm going to do that 10a crack. Just to do something.”

In eight minutes, he sailed through 150 feet of crack and chimney. Only once or twice in more than 40 years of watching others climb have I seen someone move with such grace and strength, roped or unroped. I knew that a 5.10a route was easy for Honnold. But my breathing went back to normal only when he had safely returned to the base of the wall.

In 2008, Boulder-based Sender Films asked Honnold to reenact his solos on Moonlight Buttress and Half Dome. The 24-minute movie that resulted, “Alone on the Wall,” became a smash hit on the adventure-film circuit in 2009 and 2010, snagging major prizes at Mountainfilm and the Trento Film Festival in Italy.

Every time the climactic segment of “Alone on the Wall” unreels, the same thing happens: when Honnold leans back against the cliff, 1,800 feet above the ground, the audience gasps, as if the air has been sucked out of the theater. A still from the film, of Honnold frozen on Thank God Ledge, has become an iconic image in the adventure world, appearing in magazine ads for The North Face.

This sort of promotion raises a disturbing question: Could the attention from magazines, filmmakers, and sponsors tempt Honnold into a fatal mistake?

He rejects that possibility. “I did all those climbs for myself,” he says. “I didn't care what anybody else thought. Fame is a perk. It's recognition of a job well done.” He adds, “My sponsors don't even know what I'm doing.”

Not everyone sees it that way. “If Alex pulls off some heinous big-wall free solo, The North Face will act like they own it,” says one jaded observer of the sponsorship scene. “But if he falls off and dies, they'll do their best to distance themselves from him.”

I asked Katie Ramage, sports marketing director for The North Face, whether she worries about rewarding Honnold for taking risks.

“We never push any of our Global Team athletes to do anything,” she said. “We try to create an environment in which they can do what they want to do. We try to bring in safety nets, in the form of gear and support. Alex is smart, strategic, very calculating in making his decisions. If he was an irresponsible thrill seeker, we wouldn't touch him.”

“If he quit free soloing,” I asked, “would you still sponsor him?”

“I'd be thrilled if he quit soloing. When we get involved with an athlete, it's for life.”

Last November, at the Banff Mountain Film Festival, I asked Peter Mortimer, codirector of “Alone on the Wall,” if he was concerned about pressuring Honnold.

“I worry for sure about him risking his life with the camera on,” said Mortimer. “If we pose him on a wall and he slips and falls and dies, I'd feel 100 percent responsible.”

Then Honnold, who was sitting next to Mortimer, interjected: “Yeah, but if I fell 70 feet and broke my ankle, you'd say, 'Great! Can you do it again?'”

ÔÇőHonnold didn't spend much time rehearsing the free solo of Half Dome. On September 5, 2008, the afternoon before the climb, he called up Weidner and revealed his plans. During the conversation, he admitted that he had climbed the route with ropes only twice before. A soloist such as Peter Croft would typically climb a route dozens of times before trying it without a rope.

“Dude, that's crazy,” Weidner said. “You should rehearse the hell out of it on a top rope before you try to solo it.”

“Nah,” said Honnold. “I want to keep it exciting.”

“Are you fucking crazy?”

Weidner knew he couldn't talk his friend out of the plan. Before he hung up, he said, 'OK, dude. I love you. Be careful.'”

The next day, Honnold was poised just above Thank God Ledge, his mind racing, his mental armor in pieces. He was so close to the top that he could hear the chatter of hikers who had come up the back side of Half Dome on a steep trail safeguarded by a pair of metal handrails.

For five long minutes that Honnold would later describe as a “very private hell,” he dipped first one hand, then the other, into his chalk bag, trying to give his fingertips better purchase on the tiny wrinkles in the stone. His feet were poised on “smears”ÔÇösmooth planes of granite. To stand there, Honnold had to contort his ankles so that the front half of each soleÔÇönot merely the toesÔÇöpressed flat against the smears. His calves cramped with the strain, and he knew he couldn't lingerÔÇöhe'd soon start suffering from sewing-machine leg, uncontrollable spasms that would jar him loose from his hold on the world. He put all his weight first on one foot, then on the other, as he tried to shake out the cramps in his calves.

To make the move, Honnold had to plant his right foot on a smooth patch of stone, then step up and reach for a “jug”ÔÇöa generous, sharp-cut edge of rock that would hold his weight. He took a deep breath and stepped up with his right foot. He glided upward, muscles screaming, and grabbed the jug.

Minutes later, Honnold pulled himself onto the summit. There, he faced a crowd of tourists. All of Yosemite stretched beneath him: El Capitan to the west, the High Sierra to the east. Far below, the Merced River wound along the valley floor. The hikers chatted on, not paying Honnold any attention.

“Maybe they thought I was a lost hiker,” he later wrote. “Maybe they didn't give a shit. Part of me wished that someone on top, anyone, had noticed that I'd just done something noteworthy.”

Then he reached down, unlaced his shoes, and began walking barefoot down the trail, back to his van.