Colin Haley is hanging out with his parents in the living room of their $900,000 home, in an upscale suburb on Mercer Island, near Seattle, explaining to me why he’s not likely to get killed climbing mountains.

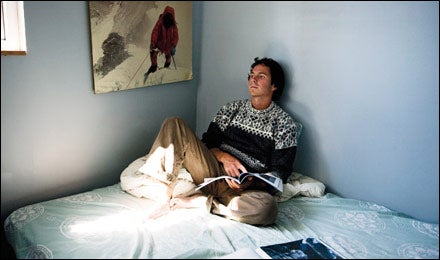

Portrait of Colin Haley in the sun

I'm 100 percent aware of the risks I take: Haley in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness

I'm 100 percent aware of the risks I take: Haley in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness“I think people see the risks that I take as greater than they are because they don’t see the thinking behind them,” he says, sitting in an armchair while kneading a cat. “For example, when I tried intravenous heroin, it wasn’t like I was drunk at some party and someone was like, ‘Do you want to shoot up?’ and I was like, ‘Oh, sure!’ I researched online what a safe dosage is and how to know a needle is totally sterile. It wasn’t some rash decision.”

We’ve been on the subject of Colin’s rapid rise as a world-class alpinist┬Śat only 24, the University of Washington senior has already established himself as a major talent, with half a dozen cutting-edge climbs in Alaska, Canada, and South America over the past two years. By definition, that means he’s pursuing very dangerous objectives, but Haley’s parents have always encouraged their son to find his own limits, so their reaction to his drug analogy comes as no surprise. His father, Jeff, gets a thoughtful look on his face and chimes in with this: “I think your first experience was safer than my first experience.”

His mother, Misty, salt-and-pepper-haired and effervescent, turns to her son, sounding concerned. “I thought that was your only experience,” she says.

“Well,” Colin says with a wry grin. “That was my only experience other than the time I took heroin through the nose.”

Misty pauses a moment to probe her memory. “Oh, right,” she says, relieved.

IT’S PROBABLY NO ACCIDENT that one of the most precocious young climbers around emerged from this creative and unorthodox family. Jeff Haley, 59, is a bookish-looking former patent attorney and advocate for progressive drug laws whose hobbies range from mountaineering to contra dancing. He’s also a garage inventor, most successfully of CankerMelts, a mouth-sore medication that sells at Rite-Aid. Misty, 62, was a world traveler who bounced between various legal-field jobs; she’s now a psychotherapist, counseling domestic-violence offenders and performing court-ordered parenting evaluations. “You know, like total crazy parents,” she says.

Though Colin has sworn off drugs and alcohol to stay in peak condition for climbing, his adolescent partying was never discouraged. “Colin learned to determine his own boundaries, to find out what he can do, to test his skills from the time he was crawling,” Jeff says. “Drugs are part of reality. You can’t deny that part of reality and raise people who are adjusted to reality.”

The family home┬Śthe staging area for this carnival of eccentricity┬Śis spacious, light-filled, and distinctly informal. “Does it smell like cat pee in here?” Misty asked, beaming, when she first greeted me in the living room. “Tell me the truth.” It did, but no one cared. The Haleys seem to revel in their quirky dishevelment. The kitchen counters are piled with dishes; the carpet has been grimed by a parade of pets.

Colin’s room, which he shows me a few minutes later, is a striking contrast. He lives in a backyard toolshed that’s been converted into a pair of 120-square-foot lofts for Haley and his 26-year-old brother, Booth. Colin sleeps on a musty mattress on the upper floor, and nothing is out of place or extraneous. The walls are decorated with pictures of forbidding peaks, like Cerro Torre and Nanga Parbat, and a bookshelf is crammed with mountaineering texts and neatly organized climbing magazines. There’s no heating or plumbing. Blue light filters onto Haley’s desk through a stained-glass image of K2, giving the room the aura of a shrine. “It’s pretty nice for a hut,” he says with pride.

The hut exemplifies the minimalism that defines Haley’s style and hints at the tremendous self-discipline that has made him one of the most exciting newcomers in years. “I want to be climbing at the cutting edge of the sport, climbing routes that are pushing the boundaries, if even just a little bit,” he says. Veteran climbers who’ve had an eye on Haley since he burst onto the scene in 2006, with the first ascent of an extreme, 7,500-foot face on Alaska’s Mount Moffit, say there’s little reason to doubt he can accomplish everything he has in mind.”He’s far and away doing harder things than most people his age, or ten years older than he is,” says Alaska climbing legend Jack Tackle, 55. “I can’t think of anyone else right now, at such an early age, who’s got as much under his belt.”

SAFELY NAVIGATING THE VERTICAL minefields of alpinism requires years of experience, and one obvious question is whether Haley will push it too hard, too soon. But so far, he’s proven himself on the highest stages. Last January, in a typically ambitious effort, Haley and an Argentine climber named Rolando Garibotti, 37, took on a project that alpinists have been fantasizing about and failing at for 20 years: the Torre Traverse.

Cerro Torre is one of the most iconic mountains in Patagonia, a 4,600-foot spire that rises like an index finger above three others, Torre Egger, Punta Herron, and Cerro Standhardt. Together, they make up a stunning, serrated fin of granite with a legendary reputation for thrashing expeditions. Torre Egger is considered the hardest summit to reach in the Western Hemisphere, and Cerro Torre is probably a close second. Climbing any of them is an incredible achievement for the best alpinists. Traversing all four in a single attempt┬Ś7,200 total feet of climbing in some of the world’s most unpredictable and unrelenting weather┬Śborders on the absurd.

On January 21, Haley and Garibotti began racing up Cerro Standhardt into a blizzard, anticipating a rare break in the icy winds that rake the peaks throughout the austral summer. To guess wrong and get caught on the ridge in a storm would force a frightening retreat┬Śhours of tedious rappels, each with progressively less protection, in vertical gullies bombarded by falling ice.

“They were out on the edge there,” says alpinist Mark Westman, 38, one of Haley’s regular partners. “If they hadn’t reached the summit, they were looking at quite an epic to get out.”At the end of the third day, the pair came to the hardest pitch of the traverse, a 160-foot-tall tower of crumbly rime that serves as the final, formidable obstacle to the top of Cerro Torre. Since this ice was too loose to hold screws or other protection, falling would likely be catastrophic.

It was Haley’s turn to lead. Belayed by Garibotti, he spent four hours carving out a chimney with an ice ax, inching higher and bracing himself in the snow tube until he popped out into the sunshine, soaking wet. Soon he was standing on the 10,262-foot summit.

How notable was this climb? Jim Donini, the 65-year-old president of the American Alpine Club and a member of the first team to climb Torre Egger, in 1976, called it “the most significant achievement of the year in the Western Hemisphere.” But it was just one of half a dozen major climbs Haley had pulled off in a furious blitz that started when he was 21. These included an earlier climb of Cerro Torre with 38-year-old Kelly Cordes; a first winter ascent of Alaska’s storied Mount Huntington with 23-year-old Jed Brown; and a stunning new route on British Columbia’s Mount Robson with America’s top alpinist, 36-year-old Steve House.

Haley always climbs alpine style, which means he goes for the summit in a lightning push with the absolute minimum gear. Climbing this way requires years of hard apprenticeship in the mountains, but most of Haley’s partners say he’s already as advanced as many of the best.”I’ve never seen anyone attain this level of proficiency and success at his age,” Donini says. “I think it’s unprecedented in American climbing. In fact, I know it is. I don’t throw praise around. I make an exception for Colin.”

HALEY LOOKS LIKE ANY other fresh-faced student on the brick-and-gothic University of Washington campus. He’s five-foot nine, 150 pounds, with broad shoulders, curly black hair, and a wide smile framed by perpetually flushed cheeks. A geology major, he rides his cheapo mountain bike, spray-painted theft-proof orange, at full tilt to classes, running yellow lights in the rain and slaloming through throngs of coeds shuffling along with umbrellas. He’s a popular guy, continually stopping for conversations, but few of his fellow students have any clue about the feats he performs in the mountains. “Usually, I just give up on explaining climbing to a non-climbing friend,” he says. “I’m just like, ‘Oh, yeah, I climb.'”

Haley is good in part because he got started early, with a focus that bordered on obsession. His father, an experienced recreational mountaineer, introduced him to difficult alpine climbing at age 12. Haley started climbing frequently in the Northern Cascades with family and friends, tearing through classic mountaineering books in his free time. “I was reading about all these big mountains, and of course I knew that if I wanted to climb these peaks someday, I’d have to climb, climb, climb,” he says. “I remember thinking, when I was 13 or so, If I climb one mountain in my life, I want to climb Cerro Torre.”

By 14, Haley was already leading most of his partners, even older ones. When he got his driver’s license, at 16, he started spending almost all his weekends in the mountains. His skill level skyrocketed, and at 17 he began taking on really serious challenges┬Ślike a solo climb of Peru’s 19,511-foot Alpamayo and the second ascent of the north face of Graybeard Peak, in Washington, which he also did alone.

By the time he was 20, Haley could match skills with climbers a decade older. Disarmingly intelligent┬Śhe yawned his way to a 1420 on his SATs┬Śhe also showed an innate talent for planning his climbs, mapping out every piece of equipment and every bivouac with a focus that allowed him to take less gear and climb more quickly, summiting and retreating before bad weather blew in.

“I’m not a very strong rock climber,” he says. “I’m not a very strong ice climber, compared to people who are at the top of those games. I think most of my climbing successes have to do with strategy, from thinking about a climb and making small adjustments to gear or route selection that add up.”

But in the mountains, know-how doesn’t always translate to summiting, which depends as much on the capriciousness of the weather as anything else. At the outer edge, the odds are almost always against completing a climb. Haley’s approach was simple: Get out there as often as possible and go for it. “He’s not a Tiger Woods kind of talent,” says House, “but I don’t think you can emphasize enough just how motivated he is to go alpine climbing.”

When the country’s best climbers found themselves short a partner for their major projects, Haley would drop everything┬Śrearranging travel plans, canceling an entire quarter of college classes┬Śat the mere hint that he could accompany them. In the 16-month period from December 2006 to March 2008, Haley spent a dizzying nine months climbing in Patagonia, Pakistan, Alaska, the Canadian Rockies, Yosemite, and the Cascades. This winter, he’s headed back to Patagonia with Garibotti, and then, postgraduation, he’s planning an extended expedition to Alaska, with an eye toward alpine test pieces like Mount Hunter, Mount Foraker, and Mount McKinley.

“He’s been back to back to back to back,” says Westman. “It’s hard to sustain that level of motivation and energy to keep traveling and keep climbing, but he’s got it.”

To do all this takes cash, and there, too, Haley has demonstrated his trademark guile. Though his well-to-do parents cover his college tuition, they don’t fund his climbing┬Śat least not directly. Haley has paid for it himself, by cramming in hours at two Seattle outdoor gear-stores, by inheriting used clothing or scavenging equipment other climbers have left behind, and by old-fashioned dirtbag scrimping. “He’s an incredible miser,” says Tim Matsui, 35, a friend and climbing partner. To save money for his 2007 Alaska trip, Haley spent his junior year sleeping on the floor of an assistant professor for $100 a month, pocketing most of the $600 his parents gave him each month for the dorms.

After Haley graduates this spring, he’ll be on his own to scrape together a professional career. He makes some money selling photographs of his climbs and has a small stipend from Patagonia that covers about a quarter of his expedition costs, but once he leaves his parents’ rent-free nest, he’ll face the true test of a professional: finding out if he can generate enough publicity for sponsors, so that he’ll be paid enough to continue climbing full-tilt.

NO ONE SUGGESTS HALEY is reckless in the mountains, not by alpinist standards. But despite his successes, there are a few who worry that his meteoric rise has happened too fast, and that his go-for-it attitude may get him in trouble.

In his immaculately organized gear room, Haley shows me a radical device called a d├ęcrocheur fifi, which he’s been experimenting with. It’s a loose hook that holds a climber’s rope to an anchor but falls instantly if he lets his weight off the rope. The advantage: By using this device, a solo climber can leave behind a heavy second rope, and descend a route faster. The drawback: Even a momentary loss of tension on the rope will drop him to his death. “I think there’s probably less than 20 people in the world who use this,” Haley tells me as his brother Booth looks on. “This is about as sketchy as climbing techniques get.” Ominously, as he starts to demonstrate, the hook flings unexpectedly off the wall and clatters onto a bureau.

“You’re dead,” says Booth. We all share a nervous laugh.

Most of Haley’s partners┬Śand most everyone who knows him┬Śsay he’s uncommonly mature for his age. “He found what he wanted to do early in life, he’s sure of himself, and it translated into him being a climber who makes very intelligent and very prudent decisions,” says Westman, voicing a sentiment I heard echoed by Garibotti, Cordes, and many others. “Colin has no lack of confidence,” Garibotti says, “but I don’t see the sign of someone who is throwing himself at climbing in an unprepared manner and is going to have a tragedy. He seems really old for his age.”

Still, Haley’s off-the-charts motivation puts him in the line of fire more often than others. “I don’t want other people to judge him based on second- or third-hand info, but, yeah, I’ve seen him make decisions that, in hindsight, weren’t the best,” says House. “I told him that, and he kind of did it anyway. He still has some learning to do.”

House and Scott Johnston, 55┬Śwho climbed with Haley in Alaska and Pakistan┬Ścan recall a handful of examples in which Haley’s enthusiasm led him to pick unnecessarily risky routes or eagerly push on in conditions that experienced climbers probably wouldn’t have risked.

In one instance, on Mount McKinley in 2005, Johnston and Haley, then 20, were unroped, descending a long runnel of black ice midway through the climb. A TV-size boulder, melted loose by warm temperatures, came ricocheting down the tight gulley, straight at them. They survived thanks to a lucky bounce. Johnston, a longtime guide, recalls having to convince Haley that they were moving too slowly and needed to abort the attempt. “That’s when the lightbulb went off for me,” Johnston says. “Colin’s risk tolerance was way bigger than mine. He would have continued on. I feel like it would not have been a good decision.” Haley responds that he was ready to safely continue and that the decision “really had to do with the difference in age and fitness.”

There’s no question Haley is bold. After Johnston backed out of their plans to climb the Schell Route, on Pakistan’s 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat, in 2005, Haley tried to solo it┬Śdespite never having attempted an 8,000-meter peak. A little more than halfway up, a storm forced him to retreat. At base camp, House had tried to talk him out of it, to no avail.

“Both Steve and I shook our heads and said this is not a good thing,” Johnston says. “We were hoping with Steve’s reputation, he’d listen. That was one of those instances where his hubris outweighed his judgment.

“I don’t want to denigrate Colin in any way,” he adds. “If this guy lives through this, he’s going to be an amazing climber. But he is right on the edge where he could be killed at any moment. He’s pursuing dangerous alpine problems with the main tool being his unbridled enthusiasm. That’s what made me nervous.”

Haley sees it differently. “I’m 100 percent just as aware of the risks I take as someone who is much older,” he says, “but if I’m going to do hard alpine climbing that has inherent risks, now is the absolute best time in my life to do it.”

To some degree, Haley’s ambition simply mirrors what is expected in alpinism these days. “To be on the cutting edge now, in 2008, with the first ascents that are left, you’ve got to hang it out a little bit more than you did 20 years ago, when there were a lot more plums to pick,” says Donini.

This summer, Haley and another talented young climber, Canadian Maxime Turgeon, 28, were in Pakistan for an audacious alpine-style attempt on the Ogre, a remote, 23,900-foot cone in the Karakoram Range that’s been climbed only twice, and never alpine style. They were shut down by the weather, but their ambition spoke volumes.

“I’ve said to everyone, the most important thing for Colin is to live through the next ten years,” says House. “If he can do that, then look out. Because he’s going to have more experience than any of us.”

ON A SATURDAY IN JUNE, Haley drives me out to Leavenworth, Washington, for a weekend of climbing in the Cascades. His gray 1997 Subaru Legacy, which the family bought used, looks to be on its last legs. It hasn’t had an oil change in 16 months. We arrive at the trailhead amid the smell of burning oil.

Haley has lined up an ambitious weekend┬Śwe’ll do two multipitch rock climbs in two days, interspersed with 20 miles of hiking, bookended by long drives. Every item, down to a single Gu packet, has been carefully considered, and only the barest essentials made the bag. The 50-meter, 8.5-millimeter rope that we’ll use is thinner than is recommended for rock climbing, since it’s more likely to be cut on a sharp edge and snap. But it shaved a few pounds off our backs, which is critical, since Haley hikes faster than some people run.

Haley leads me up Outer Space, a meandering route on a 600-foot shield of granite in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. Above the first pitch, there’s a fourth-class scramble across a terraced shoulder to the next belay. It’s not especially dangerous, but it’s still quite steep. Haley suggests that we just climb it simultaneously, tied together but without a belay anchor, so we can move faster. The idea makes me a little nervous, and I say so. He considers the terrain and then politely suggests again. “Why don’t we do this: Why don’t you trust my judgment, and we’ll simul-climb a little ways?” he says, smiling. “It’ll be fine.”

I’m reminded of something Cordes wrote in an e-mail before I went to Seattle: “For sure, there’s a bit of a question as to what will happen with Colin.” He might keep going at his breakneck pace, he might quit climbing altogether, or he might get killed┬Śas might any climber at the top of the game. “After all,” Cordes wrote, “corny as it sounds, that unknown is the very essence of hard alpinism.”

It’s also why we watch or, in whatever pedestrian way we can, follow. Haley turns and resumes climbing. The thin rope grows taut between us. I dismantle our anchor, take a breath, and follow him onto the ledge.