GO HOME, ARON, THE VOICE SAYS. PUT YOUR SKIS ON, ENJOY THE RIDE DOWN. YOU’VE CLIMBED 58 OF THESE FOURTEENERS—YOU DON’T NEED ANOTHER. C’MON, LET IT BE.

Aron Ralston

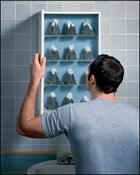

Photo Illustration by Mark Hooper

Photo Illustration by Mark HooperAron Ralston

From left: 2/7/03 > Capitol Peak; 3/17/04 > El Diente Peak; 3-14-03 > North Maroon Peak

From left: 2/7/03 > Capitol Peak; 3/17/04 > El Diente Peak; 3-14-03 > North Maroon PeakAron Ralston

From left: 1/27/05 > Redcloud Peak; 1/27/01 > Little Bear Peak; 3/6/05 > Sunlight Peak

From left: 1/27/05 > Redcloud Peak; 1/27/01 > Little Bear Peak; 3/6/05 > Sunlight PeakAron Ralston

From left: 12/23/01 > Grays Peak; 1/25/03 > Longs Peak; 1/13/01 > Mount Antero

From left: 12/23/01 > Grays Peak; 1/25/03 > Longs Peak; 1/13/01 > Mount AnteroAron Ralston

NOW WHAT? Ralston beside Colorado’s Animas River on March 8, 2005, the day after completing his seven-winter project.

NOW WHAT? Ralston beside Colorado’s Animas River on March 8, 2005, the day after completing his seven-winter project.It’s a cold March morning, and I’m standing at 13,800 feet on the snow-filled saddle between the north and south summits of 14,083-foot Mount Eolus, in the Needles of southwestern Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. Squinting behind my darkest sunglasses against the high-altitude sun, I scan for a single piece of evidence that might disprove the illusion that I am the only human within 50 miles. But I seem to have the planet to myself—or at least the hundreds of peaks and ridges in Colorado’s largest wilderness, an exquisite nowhere that includes 28 of the 100 highest mountains in the 3,000-mile Rocky Mountain chain.

Of all those ridgelines, I’m staring ahead at one: the Catwalk, an exposed, snow-riddled knife-edge that separates me from the final 300 vertical feet of a seven-winter mountaineering project. In 1997, I set out to climb all of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, alone and in winter, and Eolus is my last. Now, after three strenuous days on the approach, I stand just an hour from the summit and consider calling the whole thing off.

But then another voice interrupts: This is the last mountain. Conditions are good, the weather’s good; you’re just intimidated. Do what you do. Climb.

I inch forward. A third of the way out, I pause at a spot where a lonesome rocky knuckle disappears below a double-edged cornice stretching ahead for 50 yards. True to the mountain’s namesake, Aeolus—ancient Greek custodian of the four winds—swirling, winter-long gusts have built the snow into cantilevered curls that droop under their own weight like the furling wings of an albino manta ray. I’ll have to trace the exact crest of the underlying rocks, mindful that with each step one of my cramponed ski boots could sink unexpectedly and throw me catastrophically off balance. A mistake could dislodge the entire snowpack, sending me and several tons of snow crashing down a thousand feet.

Looking back toward the summit of North Eolus, I can see an enormous cross of snow set in the pink granite. Back in the summer of 1999, I watched from a nearby valley as a rescue helicopter hovered above that cross, dangling a haul line down to the body of a fallen mountaineer. Blocking out visions of a helicopter short-haul involving my own lifeless form, I advance nearly doubled over, probing with my ice ax in my left hand as I balance my weight on the ski pole clamped in the prosthetic gripper I wear on my handless right arm. When the ax strikes buried rock, I move, reassured. When it doesn’t, I’m all too aware that my next step could be a fatal one.

THE YEARS AGO, GETTING TO THIS POINT would have been unthinkable. Sure, I’d reached summits before—riding lifts to the peaks of ski areas near my hometown of Denver in high school. But the first mountain I ever walked up was in the summer of 1994, after my freshman year at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University, when my best friend, Jon, and I climbed 14,255-foot Longs Peak, in Rocky Mountain National Park. If I had previously questioned my spiritual place in nature, here it was, perfectly clear and understandable when seen from that high mountaintop.

Even before I climbed Longs, I’d heard about people hiking all the fourteeners. Colorado has the highest concentration of 14,000-foot peaks of any state—54 according to the Colorado Mountain Club (CMC), though the exact number is open to debate. Beginning in the 1920s, the CMC has kept the list that most people go by, evaluating peaks since 1968 by the “300-Foot Rule,” which states that, to be ranked as a fourteener in its own right, a summit generally must rise 300 vertical feet above the saddle connecting it with a higher mountain. But some climbers, me among them, prefer an exclusively topographical list of the U.S. Geological Survey’s 59 named or ranked peaks above 14,000 feet.

However you count them, the mystique of the fourteeners is undeniable. At 14,433 feet, Mount Elbert is the highest peak in the Rockies; the east face of Longs, known as the Diamond, holds dozens of the hardest high-altitude climbing routes in North America. For millions of people a year, merely standing in the shadow of the Maroon Bells or Pikes Peak—whose views inspired the lyrics of America the Beautiful in 1893—is worth the pilgrimage. And for generations of hikers, the fourteeners inspire a more exalted sort of passion, the kind exhibited by the elderly gentleman who plopped down next to me on the summit of 14,150-foot Mount Sneffels, near Telluride, and explained between panting breaths that he’d drunk a beer on top of every fourteener. Sneffels was his last peak, and to celebrate, he pulled a five-liter keg of Warsteiner out of his pack. My descent was understandably wobbly.

Since 1923, when young Denver businessmen Carl Blaurock and William Ervin climbed all 46 of the state’s then-measured 14,000-foot peaks, the CMC estimates that nearly 1,200 people have summited all the fourteeners, even fewer than have scaled Mount Everest. Over the years, as better mapping and technology helped the USGS refine peak elevations, the number of recognized fourteeners grew—and the records piled up. In 1937, Breckenridge teacher Carl Melzer and his nine-year-old son, Bob, became the first to climb all 51 of the known fourteeners in a single season. By 1959, the USGS had recognized an additional mountain, and pioneering climber Cleve McCarty knocked off all 52 in 52 days—perhaps the most symmetrical feat of Colorado peak bagging. The current speed record stands at just over 10 days and 20 hours, set in 2000 by Oregon speed hiker Ted “Cave Dog” Keizer.

The summit chase is hardly confined to summer. In 1991, Carbondale, Colorado, writer Louis Dawson II—author of the definitive two-volume Dawson’s Guide to Colorado’s Fourteeners—became the only person to ski down every fourteener. It took him 14 years. This winter, two of my friends from Aspen, 33-year-old ski instructor Ted Mahon and two-time world extreme-skiing champion Chris Davenport, 35, are following in his tracks. Ted has 15 peaks left before he becomes the first to duplicate Dawson’s feat. Chris is attempting to go one better: to ski the fourteeners in a single snow season.

I found myself drawn to the winter wilderness as well. Approximately 500,000 people set out on a trail to a fourteener each summer, according to the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, a partnership of nonprofits dedicated to protecting these mountains. When I hiked 14,270-foot Grays and 14,267-foot Torreys peaks—two of the closest to Denver and Boulder—on a September weekend in 1997, it seemed like I passed half of those people on my way up and the other half on my way down.

At the time, I was just out of college, working in Chandler, Arizona, as a mechanical engineer for Intel, the computer-chip manufacturer. One night that fall, sitting on my bed combing through Dawson’s Guide, I noticed something. “To date,” Dawson wrote, “only one man, Tom Mereness of Boulder, Colorado, has climbed all 54 official fourteeners in winter.” I pulled out my other guidebook, Gerry Roach’s Colorado’s Fourteeners. “Hard-core mountaineers climb all the fourteeners in winter,” it pronounced. “This is a difficult goal for a single individual.” Now I had an epiphany.

I’d harbored aspirations of being hardcore myself, and it appeared that Mereness (like Dawson) had climbed with various partners. Nobody, I realized, had climbed the fourteeners in winter alone. Since high school, I’d wanted to be the first person to do something exploratory. Here was my chance.

At this point I’d hiked seven of the fourteeners, and none of the difficult ones. It took a year of research and training, including a trial expedition up Arizona’s highest mountain, 12,633-foot Humphreys Peak, before I felt ready to tackle my first winter fourteener—14,265-foot Quandary Peak, just south of Breckenridge—in December 1998. In retrospect, that kickoff climb was an utter farce, one that still slightly embarrasses me. I left my two-wheel-drive Honda CRX where it could no longer climb the snowpacked forest road and snowshoed up through the woods. Above tree line, the wind turned my uninsulated water bottles, candy bars, and peanut-butter-and-jelly burritos into useless bricks. Still, I was enraptured—I was soloing a fourteener in winter! Grinning naively, I struggled upward, bundling myself tighter in my ski jacket and pants, worn over manifold layers of cotton: turtleneck, hooded sweatshirt, and sweatpants. My breath fogged my goggles, then froze into shrouds of frost. When I tried wiping them clean, the Kevlar coating on my gloves etched the lenses as though I’d scoured them with sandpaper.

For two hours I trudged into the wind, nearly blind, without food or water, gasping for breath. Despite the hardships, or maybe because of them, I was euphoric when I finally reached the top. If the views from Longs Peak had set the hook, then Quandary’s western vista of the Collegiate Peaks—the greatest concentration of fourteeners in the state—reeled me in. I fantasized that, at that moment, I was higher than any other person in North America. Even the carnivorous chill that snacked on my core through the sweat-laden layers couldn’t strip the smile from my face. I was already discovering that I had a lot more inside me than I’d supposed.

Now I just needed to do something about all that cotton.

TO SAY I WAS UNDERQUALIFIED at the outset would be euphemistic; I was an overambitious kid, with far more enthusiasm than talent or skill. When I conceived the idea, I’d never held an ice ax, put on crampons, gone snow camping, dug a snow cave, or even skied off-piste. And my plan was to go unsupported and unmechanized, meaning no partners, no snowmobiles, no chance of avalanche rescue. Without training, as my concerned Intel friend and mountaineering mentor Mark Van Eeckhout pointed out over the phone one night, the project would likely kill me. This wasn’t news to me: I was well aware of my inexperience. But I also knew how to learn.

For an engineer, little is more satisfying than a well-defined objective with easily tracked milestones, and, beginning in September 1999, when I transferred to Intel’s Rio Rancho plant, just outside Albuquerque, New Mexico, I committed all my resources to the project. I read mountaineering book after mountaineering book. I enlisted Mark to teach me the basics of backcountry travel. I volunteered on the Albuquerque Mountain Rescue Council, attended the Silverton Avalanche School, in Colorado’s San Juans, and spent my summer weekends reconning the peaks. I also bought some polypropylene.

It’s easy to find people who are young and stupid. It’s harder to find someone older and still stupid. I didn’t want to be that guy, but sometimes it seemed like my destiny. I made just about every mistake possible, some of them more than once. A few (like forgetting the toilet paper) I seemed to like so well that I repeated them every season.

But I got better—even though I rang in the millennium with a Gorbachevian blotch of frostnip on my forehead. (That was a Christmas gift from 14,172-foot Mount Bross, where I’d cluelessly worn my headlamp all day, allowing the 100-mile-per-hour summit winds to conduct the cold straight through my hat and headband.) Almost every weekend for three winters, I’d drive north from Albuquerque to Colorado, careful to leave word with friends about my plans and to put a detailed note about my route on the dash of my car, legible from the outside. My strategy was to start with the easiest, most accessible peaks: the Mosquito and Front ranges, closest to Denver, then the Sangre de Cristos and the Sawatch Range, flanking the San Luis and Arkansas valleys in the center of the state. I’d leave after work on Friday, climb Saturday and Sunday, and return post-midnight in time for work. I figured I was running about $300 per summit in gas, gear, and expenses—about $18,000 over the course of the project—not to mention the $6,000 I spent fixing my truck after I hit a deer one night south of Leadville.

The personal costs were harder to quantify. I hadn’t turned into a hermit—I still saw my friends on weeknights, road-tripped with my high school buddies, and visited my family in Denver—but I was vaguely aware that I was holding even the people closest to me at a subtle distance. I realized I’d made a conscious decision to defer having a serious girlfriend; I couldn’t be fully available to someone when my passions were so wrapped up in my quest. However, I also saw altruism in my goal. I figured that if I, as unremarkable and average as I am, could do something historic, it might inspire others to dream big, too.

After three winters, I had 23 of the 59 under my belt. My mountain-rescue friends had taught me to telemark, and skinning up the peaks and skiing down was both a huge improvement over snowshoeing and an opportunity for spectacular ass-over-teakettle crashes. I progressively minimized my bivouac kit down to a lightweight down jacket, stove, fuel, pot, and lighter and quickly figured out which foods were most readily swallowed sans saliva. The best were Odwalla super-protein drinks or Gatorade, warmed up and kept insulated inside the jacket in my pack; gels like Clif Shots that I could thaw in my glove, as long as I had some unfrozen water for a chaser; and—my favorite—soggy, dashboard-thawed Patio-brand burritos.

By the end of winter 2002, I was up to 36, and I started planning my endgame. For a year, I’d been ready to move to Colorado and leave my engineering career behind; that March, I got a sign. At the edge of a willow meadow on the west side of 14,421-foot Mount Massive, I stopped short as three gray wolves loped down a hillside not 30 yards to my left—this in a region where wolves had supposedly been extinct for 60 years. The two summits I reached that day were superfluous. For weeks, I replayed what I’d witnessed like a hayseed abducted by aliens; the Forest Service representative in Leadville even responded in a strained X Files whisper: “I knew it—I knew they were out there.” If those wolves could migrate from as far away as, I imagined, Yellowstone, then I could make the move, too.

A few weeks later, I quit my job at Intel. Actually, I called it my retirement. I sold my furniture, rented out my townhouse, bought a camper shell for my truck, and traveled around climbing for six months. That fall, I moved into a low-rent group house in Aspen and got a job at a mountaineering shop.

I had 23 mountains left—the toughest on the list. I was getting to the good part. During the winter of 2003, I climbed Longs, Holy Cross, and the seven summits of the Elks Range, around Aspen—including Capitol and Pyramid peaks and the Maroon Bells, whose steep slopes, technical ridges, complicated route finding, loose rock, and avalanche exposure made them the most dangerous of the lot. The scariest moments of the whole project came on a weekly basis: I fell a sobering six feet off the pinnacled summit ridge of Pyramid, pushed through a brutal night storm on Holy Cross, got frostbite on eight fingers on Capitol, and, on Longs Peak, slipped while descending a steep slab of verglased granite just below the summit and slid toward the nothingness below.

In that eternity before the pick of my ice ax caught on the bare rock, I was more terrified than I’d ever been. But my guardian angels were working overtime that season. Indeed, my closest brush with death came not as part of the solo project but when I was on vacation from it.

IN APRIL 2003, I was hiking alone eight miles from the nearest dirt road in Utah’s Blue John Canyon, near Canyonlands National Park, when I pulled an 800-pound sandstone boulder down onto my right hand and forearm. The stone pinned me in place for five nights and six days. To survive, I drank my own urine, and then, finally, was able to escape by breaking the bones of my forearm and cutting through the remaining tissue with my El Cheapo multitool, amputating my hand just above the wrist. A highway-patrol helicopter on a search initiated by my mother found me nearly five hours later, bleeding to death on a futile march to my truck. I was saved.

I had a lot of time in the canyon to think about my life. More than anything else, I realized, what sustained me were thoughts of my friends and family—my parents, Donna and Larry, and my sister, Sonja. But I also had the self-knowledge, confidence, and determination I’d cultivated on the winter peaks, and it all came together to help me survive, even when the torture of dehydration, hunger, pain, sleep deprivation, and hypothermia made death the more pleasant option. After struggling through five surgeries and three weeks in the hospital, I was released into the nurturing care of my family.

Throughout the agony and improvements of that summer, my parents and I were amazed at how quickly I was able to relearn everything, from brushing my teeth left-handed to typing, tying my shoes, and driving my stick-shift truck. As much as I cherished that time, after four months living in my parents’ TV room, I was ready to get out of Denver and return to the mountains.

It was a bold process to think about mountaineering when I had to rely on 18 pills of narcotics a day just to walk down the grocery-store aisle to pick up even more narcotics. But I sincerely felt that God had given me a new life, complete with the ability to walk in nature, and I missed the high country. Surely, I was content simply to be alive. But I needed the chance to prove to myself that I could regain my self-reliance. So I pushed. First to get off the painkillers, then the IV antibiotics, then to start walking and even running, all in the first month, just because I could.

Curiously, my recovery wasn’t the most difficult thing I’d ever laid out for myself. That distinction goes to my decision to leave my engineering career. In the canyon, I realized how proud I was that I’d found the courage to resign, how right I’d been to give up security for adventure. All along in my fourteener project, I’d hoped to be the kind of person whose example stirred others to reach their potential as well. Once my story hit the media, there was astronomically more interest in that message. But I also had critics.

I don’t mean the friends who teased, “Make sure you tell someone where you’re going,” which I’ve always done when I go solo into the backcountry—except for that one fateful trip. I’m referring, rather, to people who wrote to magazines or anonymously posted messages on online discussion groups or sent me letters saying that because I’d taken what were, in their view, unnecessary risks, I didn’t deserve to be rescued from Blue John.

A few chastised me that I obviously hadn’t learned my lesson or that I was a bad role model. Now, I’m not going to suggest that everyone should take up solo winter mountaineering. But we all bring risk into our lives, through our choices about how we make a living, how we drive, how we party, and how we eat: It’s far riskier to be a McFood-pounding smoker than to climb solo. If it seems that I fill my days with moments that cause my heart to bound, my breath to rush, that’s because those are the times I feel most alive.

Had it not been for the fourteeners project, I would not have recovered as quickly as I did. The ten months between my release from the hospital and my first post-accident attempt at a winter fourteener play in my memory like a Rocky comeback montage: At first, it’s all I can do to walk out into my parents’ backyard. But then the theme song kicks in as I go running up to 8,600 feet on the Incline, a steep abandoned railroad bed on Pikes Peak. Next I’m blazing up Kelso Ridge, on Torreys Peak, my first time soloing above 14,000 feet, and then my friend Jason and I are out traversing five fourteeners in 30 hours. The music climaxes as I cross the finish line of an adventure race in Minnesota, my teammates raising my left hand and my right stump in triumph.

Still, I lived with constant doubts about whether I’d ever be able to venture into the winter wilderness again. My truncated right arm was swollen, weak, and painful; it tingled with the phantom sensation of my hand and was extraordinarily sensitive to pressure. Unlike people born with limb differences, who build up a lifetime of calluses, I knew that if I wanted to climb I would have to do so with a prosthetic. Just after Fourth of July 2003—against the advice of my doctor and prosthetist and certainly to the chagrin of my mom—my friend Rick and I took my brand-new $30,000 myoelectric arm out for a test drive in Castlewood Canyon, southeast of Denver.

State-of-the-art as it was, the device wasn’t meant for active outdoor use, and certainly not for rock climbing. But starting on easy crags that morning, I worked my way up to, well, still fairly easy but much longer walls over the next month. The evidence was clear to me: I could climb. The prosthetic, however, needed work. The smooth off-the-shelf hook slipped around on the holds, I scratched the casing to shreds, and the entire thing threatened to slide clean off my arm with the slightest perspiration.

Malcolm Daly, president of the Louisville, Colorado–based gear company Trango and an amputee climber himself, helped me design a more advanced device—consisting of the head of an ice ax mounted onto the end of a rubber-coated prosthetic casing, with a harness system that allows me to hang from the arm. Therapeutic Recreation Systems and Hanger Prosthetics & Orthotics built the tool and arm in just a few weeks. Despite the fact that, like all prosthetics, the tool can’t provide sensory feedback (I have to see the pick to place it on rock holds) and we hadn’t solved the issue of wrist flexibility (imagine climbing in a wrist cast), it performed much better.

But what about skiing? Ice climbing? Snow camping? Most critically, could I self-arrest? With my right side handicapped by a total lack of touch response, flexibility, gripping strength, accuracy, and reaction speed, I was terrified that if I fell, I would die. Time and again, though, I worked through my doubts. That winter I made my first ice climbs, on a frozen waterfall near Ouray, and my first backcountry ski trip, up 13,316-foot North Hayden Peak, near Aspen. I also practiced setting up my tent, cooking on my stove, and packing my pack, paying special attention to tricky tasks like closing zippers.

By late winter 2004, I felt as ready as I’d ever be.

THERE WERE 14 SUMMITS LEFT—all but one in the San Juan and San Miguel mountains, in the southwestern corner of the state. I decided to start right in with two of the most difficult: 14,159-foot El Diente and its parent peak, 14,246-foot Mount Wilson. I waited until March for the snowpack to settle and for my fitness to build, but I couldn’t shake the visions: I would see myself reaching for a placement with my prosthetic tool, only to have it slip off the rock or pop out of the snow, and then I’d be falling . . .

By the light of my headlamp, I left the base camp I’d established at 12,000 feet and strode quickly up the basin, crampons biting on the compacted snow. Climbing the 30-to-40-degree slopes was fun and easy, and I even wished I’d brought my skis up from camp. Then I started up a many-fingered gully that led into the Organ Pipe gendarmes, dozens of towers that stand like ranks of soldiers on the summit ridge.

I picked my way through large rocks perched upon larger rocks, at one point poking my foot down into a snow bridge and exposing a gap that plunged a hundred feet down the side of the ridge. At the last Pipe, a series of sills hung over the north face; with my body extended and my prosthesis reaching out of sight, I made a committing and unbalanced move. All the visions and fears crowded in on me; the rocks of the north face waited on the other end of a hundred feet of air. But my tool held, my weight shifted, and I was clear. I’d passed the crux.

Ten minutes later, after plowing through the great solid pillows of snow guarding the summit, I stood atop my 46th winter solo fourteener. The sobs that choked my throat reflected all the doubts, worries, anxieties, and uncertainties of the previous ten months. Looking down into the canyonlands where my accident had taken place, it was as though I could see the direct path of my rescue, rehabilitation, and recovery arcing up from the red desert straight to El Diente’s summit.

But there would be no gimmes. The next day, a few hundred feet from a reachy and difficult move at the summit of Mount Wilson, I noticed that the wrist of my prosthetic mountain ax was packed with snow. I whacked at the casing with my handheld ice tool enough to free the release button. But then the mechanism nearly fell to pieces. Of the six screws that attach the ax to the prosthetic casing, two were backed halfway out, three were loosened to their last thread, and one was simply gone.

Crap. Now, in the freezing thin air 14,000 feet above sea level, I had to disassemble the wrist, reseat the parts, and resecure the screws. It was like trying to sew a button on a shirt with one hand while wearing a mitten. The delay maddened me, until I realized what might have happened if I hadn’t checked my prosthetic gear. I would have been up on that full-stretch pull-up at the summit, my feet dangling over the chute into Bilk Basin. With all my body weight hanging on the ax, I could’ve easily pulled it apart.

Whoa. This wasn’t going to be easy. But I could do it, and I would finish.

AFTER THE ACCIDENT, my quest had taken on a different flavor. I found a new balance, and life was good. As I got closer to finishing, though, I reflected more and more about how the project had affected me. It had been my primary source of stress, fatigue, and sleep deprivation for so long that I wondered what life would be like without it. I knew it put my family under stress, too. My mom would take down my plans over the phone and then fret for days until I called to check in. But we both knew it was what I needed to do, and she supported me, as she always has.

Still, I wondered, had that stress and fear hardened me irreversibly? I’m sure I distanced myself from potential friends, both before and after the accident. And yet today, after all those years of not even wanting a girlfriend, I’ve met someone special. We travel and go on adventures together, and I’ve been able to open up and share a closeness with her that I haven’t enjoyed for ten years. More than anything, though, I work hard to express my gratitude for the patience of my family and friends. I realize that, in many ways, my fourteener quest wasn’t a solo project at all.

I also know that my life has found a greater purpose, and the ripples keep spreading. I continue to volunteer with at-risk kids, disabled servicemen and -women, and in search and rescue. I donate my time and money to conservation causes, to give back to the wilderness some measure of what it has given to me.

Even the mistakes were worth it. One thing the ongoing miracle of Blue John Canyon has provided is a sense of what a privilege it is simply to feel. The moment I came to from the anesthesia in the hospital, my whole world was pain. That’s how I knew I was alive. And I carried that gratitude with me as I kept climbing fourteeners.

Between hut trips, fundraisers, concerts, a family vacation, and a January 2005 expedition up the highest peak in the Andes, 22,834-foot Aconcagua, I pounced on the next six peaks. In two short trips between avalanche cycles, I whittled my project down to the four peaks of the Chicago Basin of the San Juans: Windom, Sunlight, North Eolus, and Mount Eolus.

Because these mountains are the most remote of the entire list, Chicago Basin would require a five-night expedition. It would take two days just to skin the 15 miles up the Animas River and Needle Creek, an approach rife with avalanche hazard. But early March brought the rare combination of stable snow and stable weather, and sunny skies kept me company on my approach. I set up camp, climbed 14,082-foot Windom Peak, then skied the delectable powder off the west shoulder over to the slopes of 14,059-foot Sunlight Peak. A convoluted route on Sunlight brought me out of a rabbit hole just a few feet shy of the summit; after a dozen tries, I manteled onto the gabled summit rock, where I could look down more than a thousand feet off three sides. The next morning I easily made the top of 14,039-foot North Eolus.

And then there was one.

Now, at noon on the Catwalk on Mount Eolus, I cinch my ax leash on my left hand, check the grip of my prosthetic claw around my ski pole, and venture onto the sickeningly pitched east face. Despite my best efforts not to look down, I can feel that the face becomes vertical somewhere in the thousand feet of air below me—I am astonished that the snow is stuck onto the mountain at all. The powdery crystals squeak as my boots seem to tread in place. It’s like I’m climbing a mountain of packing bubbles.

At exactly 1:30, I reach the top of Mount Eolus. To my amazement, I have become the first person to climb all 59 of these fourteeners, in winter, alone.

Strangely, I find myself not euphoric but relieved. I’m done. Finally. I look around and notice that, appropriately, the mountain doesn’t care, the snow doesn’t care, the sky doesn’t care. The indifference is beautiful. People don’t belong here, I marvel, and yet here I am. Here and alive. Without fanfare, I think back on the peace I found on my first fourteener. That light, clear feeling is still there, after all these years.

Dangling my ski boots over the edge, I smile and take a photo looking down between my knees into the brilliant white. For all the contentment that fills me, I look forward to a juicy steak dinner, a hot tub, and a tall margarita—a time of not doing. Done now, I descend to my skis, then swoosh and rip for thousands of feet.