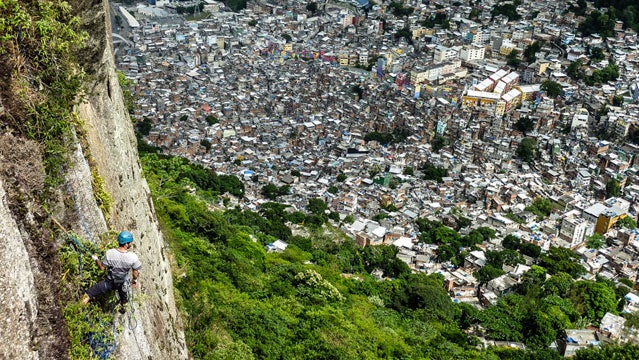

Look west along the coast from Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, and you'll see the Dois Irmaos, a two-pronged granite tooth that towers 1,700 feet over the Atlantic Ocean. Below sits the neighborhood of Rocinha, a densely-packed urban slum of steel-roofed buildings that spills down the mountain's flanks.

The Dois Irmaos tower over Ipanema Beach.

The Dois Irmaos tower over Ipanema Beach. Asa Firestone and Andrew Lenz

Asa Firestone and Andrew Lenz Eduardo “Ducha” Pacheco with a group of students

Eduardo “Ducha” Pacheco with a group of studentsThe peaks' stone bulk loomed in the distance one morning in 2010 as Asa Firestone sped towards Rocinha, weaving through heavy traffic on the back of a motorcycle while rain pounded down around him. He and the motorcycle's driver, his friend Andrew Lenz, were on their way to the neighborhood to survey potential sites for their new climbing school, the first of its kind aimed specifically at introducing RioÔÇÖs less-privileged youth to the sport.

Compared to some of RioÔÇÖs more primitive favelas, or shantytowns, Rocinha was fairly well-developed. It had shops, a bank, and a fast-food restaurant. While police didn't patrol Rocinha, the residents had running water, and electric lines criss-crossed the streets. To Firestone, it didn't look like much of a slum at all.┬á

“As we enter the favela, I think to myself, this place is no different than the rest of Brazil, then a boy who could not be much older than 16 walks by with a smile from ear to ear and a machine gun around his neck,ÔÇØ Firestone would later write on his blog. ÔÇ£The favela world is controlled by drug lords.ÔÇØ

OUT OF ALL Rio de Janeiro's natural bountiesÔÇösun, beaches, abundant surfÔÇöits rock is the least appreciated. The city is littered with granite, from sport crags to multi-pitch monsters like the Dois IrmaosÔÇöPortuguese for Two BrothersÔÇöand Sugarloaf Mountain, a 1,300-foot dome that features prominently in pictures of RioÔÇÖs skyline.

Firestone first glimpsed the Dois Irmaos in 2003 while studying abroad in Brazil. Then a Colorado University engineering student, he had wrapped up his semester and was traveling the country in an old Volkswagen Gol, hopping from crag to crag. He was immediately captivated by the peak, but local climbers cautioned him against trying to ascend it. Too dangerous, they said. Two rival gangs, Comando Vermelho and Amigos Dos Amigos, battled for control of the neighborhood, patrolling the streets with automatic weapons and executing rivals as well as residents suspected of being police informants.

The few climbers who chose to visit the Dois Irmaos anyway did so at their own risk. ÔÇ£While finishing [our route], my friend and I ran into a group of armed robbers on the summit. They wanted money, cameras, etc,ÔÇØ one climber wrote in a 2004 trip report on the site of , a Rio-area outdoors club. ÔÇ£As we didn't have anything, only our climbing equipment (they weren't interested in it) they let us go. There are many beautiful routes in [Rio de Janeiro], but I don't think that any of them are worth the trouble we went through.ÔÇØ

The Dois Irmaos werenÔÇÖt always off-limits. During the 1960s and 70s, Brazilian climbers regularly visited, putting up classic long routes like Baden Powell (5.8). That changed in the 1980s, when drug traffickers, who had previously used Brazil mostly as a corridor for smuggling cocaine out of South America, began to take hold in Rio and other Brazilian cities, where they saw a growing demand for their products.

Now, even RocinhaÔÇÖs children felt the traffickersÔÇÖ influence on a daily basis, personified in the drug dealers stationed on corners and the armed soldados who acted as their muscle. Some kids, facing slim prospects and a widespread societal bias against favela-dwellers, would be lured into the business themselves. In a , British researcher Luke Dowdney found that on average, gang members in RioÔÇÖs favelas had dropped out of school after the fourth grade and had entered the drug trade at 13. ÔÇ£I was a child,ÔÇØ one young lookout told his field investigators, ÔÇ£but IÔÇÖm already twelve now.ÔÇØ

Seeing the inequality between Rocinha and the affluent, trendy neighborhoods like S├úo Conrado and G├ívea that bordered it gave Firestone an idea. He would establish a climbing school in Rocinha, and teach local youth to climb the cliffs that they saw every day. Maybe by exposing them to the healthy risks of rock climbing, he thought, he could give them a boost of confidence, an ÔÇ£inÔÇØ to the adventure tourism business, and a chance to learn and grow in an environment that often forced kids to grow up fast.

FIRESTONEÔÇÖS NASCENT PROJECT would remain mostly dormant until 2008, when National GeographicÔÇÖs Young Explorers program sponsored him and partner Matt Othmer on a trip to the Venezuelan Amazon. There, the pair made the first ascent of a new route up the 1,500-foot face of Acopan Tepui, a massive, flat-topped sandstone mountain that took them five days to climb. Following the success of the expedition, National Geographic helped Firestone arrange a sponsorship with one of their partners, cosmetics company KiehlÔÇÖs, who agreed to support the favela climbing school.

Two years later, on a trip to Rio, a mutual friend introduced Firestone to Lenz. A native Houstonian, Lenz had moved to Brazil with his engineer father when he was a teenager. He worked with the educational non-profit before starting , a professional climbing and sailing guide service. The idea of setting up a climbing school for RioÔÇÖs underprivileged kids had occurred to him too. With its obvious need and established infrastructure for aid groups, Rocinha seemed like a perfect place to start. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs really big,ÔÇØ says Lenz. ÔÇ£ThereÔÇÖs a lot of movement, a lot of opportunity. At the same time, thereÔÇÖs a lot of stigma.ÔÇØ

The pair hashed out a plan. Lenz would work on the ground in Rio, making contacts and doing the hands-on labor of setting up and running the school, while Firestone would drum up financial support and help with logistics from the States. Lenz quickly found his main collaborator in Eduardo ÔÇ£DuchaÔÇØ Pacheco, a certified guide and one of his main partners in Ancoraue. Together, they would form the core of a rotating cast of volunteers drawn from RioÔÇÖs climbing community.

In 2011, after several years of rejected applications, Firestone and Lenz received the . Named for a 25-year-old American alpinist who died in a car crash in 2002, the grant is awarded every year to support a project that combines climbing with a philanthropic mission. While the $1,200 the pair received wouldnÔÇÖt be enough to fully fund the school, it would be enough to help them start construction on a new climbing wall.

Through contributions from friends and acquaintances, Firestone managed to scrape together enough holds and building materials to build a woodyÔÇöa small, homemade climbing gym.

After sneaking the donated supplies into the country to avoid BrazilÔÇÖs astronomical import duties, however, Firestone faced a new problem. The spot he and Lenz had settled on to build their wallÔÇöa 20-foot-high space in a government sports complexÔÇöhad been reassigned to a ballet school without their knowledge.

After meeting with officials from SUDERJ, the state agency in charge of sports in Rio de Janeiro, Lenz and Firestone received permission to use another, bigger space in the complex, a 50-foot-high, 100-foot-wide concrete-walled corridor running along the edge of the building. Building a wall large enough for the new area would be a much bigger endeavor, one well beyond the knowledge or means that Firestone and Lenz had assembled. They considered several options, including bolting holds directly to the concrete, before finally deciding to go all-in and build a gym-quality wall. Cort Gariepy, the CEO of American climbing wall builder , agreed to help by doing the design work pro bono. The school would be responsible for the cost of materials and labor, which Firestone estimated would run them about $50,000.

ÔÇ£We have an opportunity to do something really cool here, so let's just stick to our guns,ÔÇØ says Firestone. ÔÇ£If it takes a little longer, that's OK.ÔÇØ

THE TWO AMERICANS had another big problem to deal with before they could get their school off the ground. In the eight years since Firestone had first set eyes on the Dois Irmaos, Amigos dos Amigos had consolidated their control over Rocinha. Under the leadership of Antonio Bonfim Lopes, or ÔÇ£Nem,ÔÇØ a curly-haired 35-year-old who lived in a fortified villa in the favela's upper reaches, the gang presided over a narcotics empire that, according to some estimates, brought in over $50 million per year.

If Firestone and Lenz wanted to build, they knew theyÔÇÖd eventually have to deal with the Amigos. In all likelihood, that would mean paying them off. ÔÇ£We'll probably end up giving them some money, but you never know,ÔÇØ Firestone told me in the fall of 2011. ÔÇ£It's not unknown for them to be like ÔÇÿThat's fucking cool, yeah, do it.ÔÇÖ” Without Amigos dos AmigosÔÇÖ approval, even climbing on the Dois Irmaos, in the heart of their territory, was a dangerous proposition.

But early in the morning of November 13, 2011, a force of 3,000 soldiers and police from Rio de JanieroÔÇÖs Batalh├úo de Opera├º├Áes Policiais Especiais, a heavy-duty SWAT team specializing in urban combat, stormed the slum, rolling into Rocinha in armored personnel carriers as helicopters circled above the neighborhood. The invasion was part of a larger campaign by Rio law enforcement to ÔÇ£pacifyÔÇØ the cityÔÇÖs most dangerous neighborhoods ahead of the World Cup and the Olympics by driving out drug dealers and reestablishing rule of law. Nem was arrested after police caught one of his associates trying to smuggle him past a checkpoint in the trunk of a car. By the end of the day, government forces had taken control of Rocinha without firing a shot.

With the drug dealers fleeing and a newly-installed community police force patrolling the neighborhood, the climbing school suddenly had a much clearer path ahead of it. ÔÇ£There's still a lot of drug activity going on,ÔÇØ said Firestone. ÔÇ£There's still murders, there's still police officers getting killed there. ItÔÇÖs a serious place. However, I think it makes it less complicated.ÔÇØ In December, Firestone and Lenz unveiled a new name for their school: They would be the , or Urban Climbing Center. The acronym for their new title, CEU, is Portuguese for ÔÇ£skyÔÇØ.

ATTRACTING STUDENTS TO CEU turned out to be more of a struggle than Firestone or Lenz had anticipated. Parents in Rocinha, who had no experience with rock climbing, were hesitant to let their children participate in what they perceived as a borderline-suicidal activity, despite LenzÔÇÖs and FirestoneÔÇÖs best efforts to convince them that it was less dangerous than driving through RocinhaÔÇÖs chaotic traffic. While Lenz and Ducha had taken some small groups on outings, they didnÔÇÖt have a consistent core of students.

Eventually, Lenz and Firestone forged a partnership with the , a non-profit that had already established a presence in the community and could throw their credibility behind CEUÔÇÖs efforts. Finally, in March 2011, Lenz and Ducha took CEUÔÇÖs first official group up SugarloafÔÇÖs Cost├úo route, a long, mostly non-technical scramble with a 100-foot section of 5.6. ÔÇ£We had kids who were super young, like 12, all the way up to 25, and they were all psyched,ÔÇØ says Firestone. ÔÇ£Big smiles. A lot of them were a little scared, but mostly they were just psyched.ÔÇØ

At the same time as they were beginning to introduce RocinhaÔÇÖs youth to climbing, Firestone and Lenz were working on their own projects. With the favela once again relatively safe for climbers, the Dois Irmaos were in the midst of a miniature revival. ÔÇ£The climbing scene has blown up since the police moved in,ÔÇØ Lenz said. The pairÔÇÖs contributions included a 5.12 multipitch project they dubbed Sky Wall and a number of moderate single-pitch routes established with CEUÔÇÖs students in mind.

Other local climbers began rehabilitating the Dois IrmaosÔÇÖ abandoned classics, most of which hadnÔÇÖt seen traffic in over a decade. Chief among them was Patrick White (5.10a), a system of cracks and dihedrals first climbed in the 1970s. On their first foray up the climb, Lenz and Firestone found ancient, rusted bolts, and a route that had been mostly reclaimed by the jungle. ÔÇ£Super-nasty climbing, full of dirt and cactuses,ÔÇØ Lenz said. Before long, a group of climbers from Rio had restored Patrick White to its former glory, replacing the corroded old bolts and cleaning off the grime to reveal the route beneath.

BACK AT HOME, FIRESTONE was exploring new territory of his own. After going back to school at the University of Southern California to earn his MBA, he had interned at General Electric, only to decide that he wasnÔÇÖt interested in climbing the corporate ladder.

While working on a startup developing water-saving devices for showers, Firestone had begun to ponder devoting himself full-time to his and LenzÔÇÖs project in Brazil. After some deliberation, he relocated to Boulder and founded , a for-profit company that would partner with artisans from Brazil and Peru to produce climbing accessories like chalk bags and jewelry, with part of the proceeds going to fund CEUÔÇÖs operations.

The fledgling business found a partner and supporter in Gil Weiss, a Boulder local and one of FirestoneÔÇÖs best friends. Weiss, the 29-year-old founder of guiding and media company , led a semi-nomadic climberÔÇÖs life, living out of his red Pontiac Montana van half the year and blogging about his exploits. When Weiss heard about Beyond Gear, he was immediately excited. He told Firestone that he wanted to be part of it.

ÔÇ£He helped me feel like, hey, I can really make this happen,ÔÇØ says Firestone. He decided he would give himself until the end of the year to get Beyond Gear off the ground. After that, he would reevaluate.

IN JUNE 2012, FIRESTONE, WEISS, AND THEIR FRIEND BEN HORNE, a graduate student in economics at University of California, San Diego, flew down to Peru, where they planned to meet with possible suppliers for Beyond Gear and spend some time establishing a new route up the sheer south face of Palcaraju Oeste, a 20,000-foot peak near the town of Huaraz in the countryÔÇÖs rugged northwest. The trio hired a donkey driver to take them to the base of the mountain, where they were promptly pinned down by what Firestone calls ÔÇ£unseasonably badÔÇØ conditions.

ÔÇ£It was just terrible weather,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£Snowing, weÔÇÖre postholing in there even though we had already carved out our tracks. So we wound up bailing.ÔÇØ After a week, Firestone headed home. Weiss and Horne, who had more time to attempt Palcaraju, decided to stay.

By late July, Firestone still hadnÔÇÖt heard from the climbers. With growing unease, he called a friend in Peru and ÔÇ£started to investigate what was going on, where these guys were, what was up.ÔÇØ After failing to make contact, Firestone and other friends and family of Weiss decided to call a search. With the help of Huaraz-based guide Ted Alexander, they organized a team including climbers and a private plane to look for the pair.

At Palcaraju, the rescuers found a scene of destruction. Debris from an avalanche was scattered at the base of the mountain. Weiss and HorneÔÇÖs camp was still made, but their tent was empty.

Based on footprints, an aerial survey, and the photographs found on the climbersÔÇÖ cameras, an investigation found that Weiss and Horne almost certainly made it to the top of the peak. On the way down, the two men were crossing a serac, a massive chunk of ice hanging over the edge of the ridge, when it collapsed, sending them plunging off a cliff and down the mountainside. The climbers fell about 1,000 feet to the ground, the impact scattering their equipment across the glacier. A three-person ground team found their bodies at the foot of the mountain, sunken into the snow.

WEISSÔÇÖS DEATH WAS A HUGE BLOW to Firestone, both professionally and personally. Not only had he had lost his business partner and one of his best friends, he had escaped a similar fate by pure luck. ÔÇ£Psychologically, I knew I was up there, and there was no reason why I was still around and those two guys werenÔÇÖt,ÔÇØ he says. For the next few months, he ignored Beyond Gear and CEU and lost himself in the preparations for WeissÔÇÖs memorial, a 75-person celebration of his life at the base of the Flatirons near Boulder.

By September 2012, Firestone needed to get back to work, if only to pay his bills. He had been funding Beyond Gear himself, using his credit cards, and he still had grad school loans on top of that. ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt have a team, I was by myself, I had some expenses,ÔÇØ Firestone says. ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt really have much momentum. IÔÇÖd wake up in the morning and be like, well, what am I doing?ÔÇØ

Firestone started recruiting interns from the University of Colorado and brought on an acquaintance from USC to help shape the young company. He soon convinced another friend, filmmaker Dominic Gill, to come to Boulder and help him for Beyond GearÔÇÖs inaugural campaign with Indiegogo, a Kickstarter-like crowdfunding site.

The resulting four-minute short, which juxtaposed footage of Firestone climbing in Indian Creek with clips of police patrolling RioÔÇÖs favelas, went viral within the climbing community, garnering coverage from publications like Climbing and The Joy Trip Project. Some of BrazilÔÇÖs most prominent climbing blogs picked it up; Alex Honnold shared it on his Facebook page. By the end, they had raised $16,000, with the proceeds dedicated to building a climbing wall in Rocinha.

While the money was less than a third of what Lenz and Firestone needed to complete their wall, the surge of publicity from the campaign has propelled them into 2013. CEU has received some in-kind support from corporations like Petzl and Black Diamond. Beyond Gear is in business, with an initial run of six products from t-shirts to chalk bags made of recycled tent fabric.

Lenz and CEUÔÇÖs Brazilian volunteers have taken their students out on many climbs around Rio since that first outing. TheyÔÇÖve scaled Morro da Babilonia and the fantastically exposed, sail-shaped monolith of Pedra da Gavea. TheyÔÇÖve brought kids to Urca, on the cityÔÇÖs south end, to pick up trash around the neighborhood and its nearby climbing area. Today, CEU is planning to offer a certification course in basic rock climbing, and Lenz is looking to expand their operation in Rocinha to other communities.

Neither Lenz nor Firestone expects climbing to solve all of RocinhaÔÇÖs still-significant problems. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs not the end-all solution to the favelas, thereÔÇÖs no way,ÔÇØ Firestone says. ÔÇ£However, if a couple kids become climbing guides, and they were going to become drug dealers, I think thatÔÇÖs pretty rad.ÔÇØ But thatÔÇÖs still in the future. For now, heÔÇÖs happy to give a few young people from Rocinha the chance to literally rise above favela life and, from a perch high on the cliffs above, gaze across the roofs of their community, all the way down to the sea.