One spring morning in 2014, before breakfast or even coffee, , 49, a Mount╠řEverest climber and then a professor╠řat Western Kentucky University, was walking near his tent on a remote Himalayan peak in Nepal called Himlung when he broke through a thin layer of snow and clattered 70 feet down a crevasse. He would have kept falling, almost certainly to his death, were it not for a small ice shelf spanning the fissure, upon which he miraculously, if painfully, landed.

Stunned and injuredÔÇöit would turn out heÔÇÖd broken 15 bones, dislocated his shoulder, and was bleeding internallyÔÇöAll gathered himself in the icy crypt and then, like any good scientist, began to document the ordeal. He thought of his teammates on the mountain, his students back at school, his mother at home in Georgia. They would want to know what had happened to him should he not make it, which seemed likely.

The trip had been fraught since the beginning. The five-member teamÔÇÖs initial expedition to Everest had come to an abrupt end when a massive avalanche struck the Khumbu Icefall and Base Camp, killing╠ř16 Sherpas, including one from AllÔÇÖs team. After much deliberation, they rerouted to Himlung, about 160 miles west of Everest. But his teammates were struggling with altitude and fatigue and had descended lower, leaving All by himself at Camp II, on a small snowfield at nearly 20,000 feet.

Now here he was in the crevasse, peering at a pinhole of sunlight far above. Using his one functioning arm, All fished his Sony Cyber-shot HX7 camera from╠řhis jacket pocket and aimed it at himself.

ÔÇťWell,ÔÇŁ he said, his face speckled with blood, ÔÇťIÔÇÖm pretty well fucked.ÔÇŁ

AllÔÇÖs teammates had descended to Base Camp, at least a day away. He would freeze to death before anyone could reach him, even if he had some way to contact them. (All had brought a satellite phone to the camp, but it was in his tent.) Despite his injuries, and the vertical walls of blue ice surrounding him, he would have to try to extract himself.

For the next four hours, All wormed and squirmed his way toward the surface, wedging himself between the walls, chimneying diagonally toward the surface. He hacked one ice ax ahead, then stabbed his cramponed feet upward, moving inches at a time. The pain was searing, causing him to stop often, hyperventilating, trying not to pass out. During breaks╠řhe would film himself, noting his progress. Improbably, he reached the top and punched through the snow, flopping into the horizontal world, the late-afternoon sky brilliant and blue in the thin air. It took him another two hours to crawl to his tent, where he managed to send a text message╠řfrom his satellite phone, programmed to post automatically to the American Climber Science ProgramÔÇÖs Facebook page: ÔÇťPlease call Global Rescue. John broken arm, ribs, internal bleeding. Fell 70 ft crevasse. Climbed out. Himlung Camp 2,ÔÇŁ╠řhe typed. ÔÇťPlease hurry.ÔÇŁ Group members promptly called to launch a rescue.

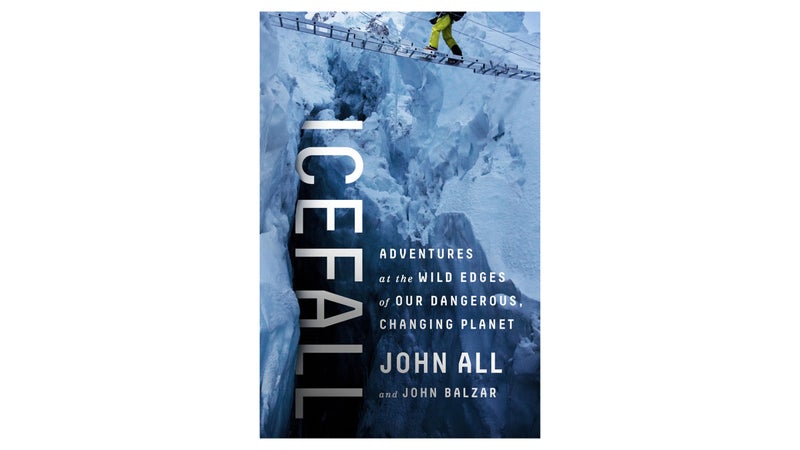

By the next day, he was at Norvic International Hospital in Kathmandu, having been plucked from the mountain by helicopter, itself a dicey operation at such extreme altitude. While recovering in the hospital, All uploaded an edited version of to YouTube, where they quickly went viral. The survival story drew comparisons to Aron RalstonÔÇÖs in ╠řand the Everest classic . All would go on to write his own book, , published in 2017.

This April, All returned to the Himalayas for the first time since his accident, bound for Everest. His life has changed considerably since his last visit, but his mission is much the same as it was in 2014: leading a team of scientists into the mountain range, two of whom will ascend Everest, while three others, including All, will attempt EverestÔÇÖs 27,940-foot next-door neighbor, Lhotse. The team will gather bits of snow and╠řice╠řalong the way, each sample another data point in the growing story of climate change.

The data is intended to shed an increasingly bright light on a complex scienceÔÇöparticularly the impact of pollution and dust in high-alpine terrain, what it says about global warming, and how that is affecting water resources╠řstored in big mountains as glacial ice. Black carbon, a sooty residue from coal-fired power plants and other fossil-fuel-burning sources, gathers easily on snowy slopes, accelerating warming and melting. ÔÇťThe Himalayas are the water supply to a billion people,ÔÇŁ All told me recently. ÔÇťWhat happens to these glaciers over the next couple of decades is going to have a huge impact.ÔÇŁ

Before people climbed for (type-two) fun, they climbed for science. The first ascent of 15,777-foot Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in the Alps, was pulled off in 1786 by two Frenchmen, Jacques Balmat and Michel-Gabriel Paccard, largely because the preeminent Swiss geologist Horace B├ęn├ędict de Saussure, who was also a climber, had offered up prize money to the first people to reach the summit. Saussure was obsessed with mountains as a focus of his research; he believed they held the key to understanding the earth. These initial summitsÔÇöSaussure himself was the third person to ascend Mont Blanc, the following yearÔÇöare widely considered to be the dawn of modern mountaineering.

Few carry SaussureÔÇÖs torch these days like John All. He, too, became fascinated with mountains and the stories they could tell about the natural world. Raised in Georgia, he made a false career start as an environmental lawyer before pivoting to science in the mid-nineties. He moved to Tucson, Arizona, to pursue a Ph.D. in renewable natural resources at the University of Arizona, where he hiked, climbed, and volunteered with search and rescue teams. His jones for mountaineering continued to expand, and in 2010, while spending a year in Nepal as a Fulbright Scholar, he summited Everest via the North Col, in Tibet.

As AllÔÇÖs life as a scientist grew and intensified, so did his adventures. He was held at gunpoint by marijuana farmers in Mexico╠řand nearly mauled by a hyena on the African veldt. He traveled to South America and pulled off perilous ascents in PeruÔÇÖs Cordillera Blanca, conducting climate research all along. At six foot five, with long blond hair, blue eyes, and a charming hint of southern drawl, his exploits werenÔÇÖt devoid of romance; as╠řIcefall mentions, various girlfriends joined him in the field. During one early trip, his partner at the time proposed to him after their car got stuck, stranding them in the desert. He said yes. (They had a son, Nathaniel, now 14, but the marriage didnÔÇÖt last.)

ÔÇťThe Himalayas are the water supply to a billion people,ÔÇŁ╠řAll told me recently. ÔÇťWhat happens to these glaciers over the next couple of decades is going to have a huge impact.ÔÇŁ

If youÔÇÖre thinking that All sounds like the Indiana Jones of climate science, you wouldnÔÇÖt be far offÔÇöthough the reality is less glamorous than the Hollywood version. AllÔÇÖs journey back to NepalÔÇÖs high peaks has been long and arduous. Despite the modest celebrity he attained in╠řthe months after his accident, away from the cameras and reporters, he gulped painkillers to help his body remember how to move again; the narcotics erased entire swaths of memory, and he couldnÔÇÖt work or do much of anything. In the fog of his debilitation, a serious but recent girlfriend left him for someone else. ÔÇťI was supposed to be this active, lively, adventure guy,ÔÇŁ All said, ÔÇťand I was just this broken-down dude on the couch.ÔÇŁ

All eventually got back on his feet, but after the difficult yearlong recovery, he needed a reboot. In 2016, he left his teaching job in Kentucky for a full╠řprofessor position at Western Washington University. At his new gig in Bellingham, All founded the . The organization would help formalize and institutionalize scientific expeditions to study climate change at high altitude. ╠ř╠ř╠ř╠ř╠ř

The team in Nepal includes two geology students from Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu╠řwho will return to school when the team heads up to Everest. The Everest climbing squad includes Morgan Scott, a grad student at WWU, and James Holmes, from New York, treasurer for the , a Colorado-based nonprofit that helps support science-based climbing trips. (All is its╠řcofounder and executive director.) Joining All on LhotseÔÇöthe climbs share the same route until about 25,250 feetÔÇöare Chris Dunn, a Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado, and Graham Vickowski, a paramedic from Washington, D.C.

The science program is twofold: During the approach to Everest, the team will collect plant data from more than 850╠řlocations, repeating a study All directed in 2009. Higher on the mountain, theyÔÇÖll gather glacier samples of snow, ice, and rock in order to analyze deposits of dust and black carbon.

The glaciers play a vital role in whatÔÇÖs known as the planetÔÇÖs╠řalbedo,╠řthe reflectivity of the earthÔÇÖs surface. The more pollutants and dust that cover a glacier, the less reflective it becomes, absorbing solar energy and creating a feedback loop that gradually raises temperatures, accelerating glacial melt and recession. A 2019 report titled ÔÇťÔÇŁ╠řnoted that╠řby 2100, temperatures in the northwest Himalayas are expected to have risen nearly 50 percent faster than the global average.╠řAnother study, from 2013, indicated that glaciers around Everest have shrunk by 13 percent since the 1960s, and the rate is increasing. Some scientists predict that at least one-third of glaciers in the Himalayas will be gone by the end of the century. Because the range is sandwiched between China and India, All hopes itÔÇÖs possible to distinguish the source of various pollutants, and, in turn, influence conservation efforts in the planetÔÇÖs two largest countries.

The team arrived in advance╠řbase camp (ABC) on April 16╠řand began sorties above camp. Its summit attempts will take place later this month, when appropriate weather windows open up and the team is rested and ready. Meanwhile, conditions appear to be quiet and stable on the mountain. They are, however, as All recently recounted on the , quite warm.

ÔÇťThe morning is clear and bright and the sun beats us unmercifully,ÔÇŁ he wrote. ÔÇťHats, sunscreen, long sleeves, sunglasses, and lip balm. The snow melts more and more quickly.ÔÇŁ