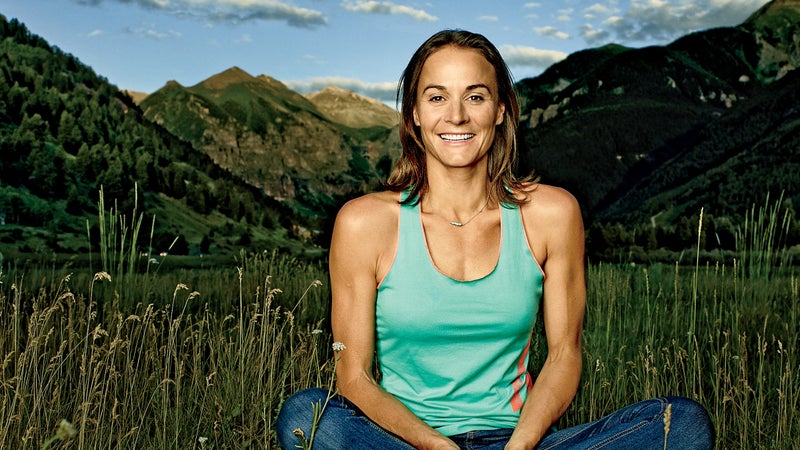

How Hilaree O’Neill Bounced Back from the Most Demoralizing Climb of Her Life

One of the best climbers of her generation points her skis down 27,766-foot Makalu

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Early last November, was on a ledge roughly 1,100 feet below the top of Hkakabo Razi, pinned down by one of the harshest winds she’d ever experienced. Hkakabo Razi, in northern Myanmar, is believed to be the highest mountain in Southeast Asia, and O’Neill was leading a two-month expedition to measure the peak’s true height. If successful, it would be only the second ascent of the relatively unexplored mountain, and a month into it her six-person team was coming apart.

O’Neill had spent two years planning the expedition, poring over Google Earth and World War II–era charts. (Modern maps of the area are nonexistent.) Her team of climbers—North Face athlete Emily Harrington, National Geographic writer , filmmaker , photographer , and , the base-camp manager—had traveled across Myanmar, then marched more than 100 miles through dense jungle as their food supplies dwindled and gear was abandoned to save weight. Once on the mountain, they climbed for five days over false summits and up dead-end routes before finally, their strength diminishing, they neared the top. Up to this point, the climbing was similar to a lot of other Himalayan peaks—snow packed into ice—but the group were unsure what conditions they would encounter on the narrow ridge leading to the summit.��

At high camp, the team discussed the summit push. Everyone agreed that a three-person team would be best. As the conversation turned to who should go, O’Neill realized the men had already decided that she should stay behind.

“Hkakabo Razi��nearly broke me,” she says. “It was almost my retirement trip.”

“The guys were seriously distressed about the safety of the team,” Jenkins later in one of many expedition blog posts on National Geographic’s website. “It was unsafe and thus unwise for Hilaree and Emily to continue the climb. Emily readily acknowledged that she did not want to go any higher; but Hilaree was deeply, furiously offended… Would ego actually trump safety?”

Ozturk caught the confrontation on film in , a documentary about the climb, which premiered last May at Mountainfilm in Telluride.��

“You don’t think I can do this and be strong and fast on it, fast enough to get us there,” O’Neill says in the film.

“You’re taking it personally,” Jenkins says.��

“Of course I am.”

As a ski mountaineer, O’Neill had covered similar terrain the year before on Papsura, a 21,165-foot peak in India. She believed that she had the strength and the résumé—35 expeditions over 15 years, ranging from mellow climbs like Kilimanjaro to a difficult ascent of Mount Waddington in British Columbia—to reach the summit. But most of all, she was shocked that the men had come to a decision without consulting her.��

“I was totally stunned by that sort of betrayal,” O’Neill recalls now. “I was also really pissed off.”

Both Jenkins and Ozturk maintain that they were merely starting the discussion about who was best suited for the technical summit push. (Richards could not be reached for comment.) Jenkins pointed out that O’Neill had been nearly hypothermic upon reaching high camp, and Ozturk said that the men had more experience with the fast, technical climbing ahead of them.

“We were trying to have an open conversation about how we could summit safely,” says Jenkins.��

Over the next several hours, the men tried to talk O’Neill out of climbing the last stretch of the peak. “It was like musical tents, everyone cycling through,” Ozturk says. Tempers flared. At one point in Down to Nothing, O’Neill says, “I’m going to say one thing, and it’s not going to be nice. Fuck you, Mark, for the vote of confidence.”

Richards eventually got tired of the arguments and said he’d give O’Neill his spot. But come summit day, she felt that conditions were too harsh and her ability to lead had been compromised. She backed down.��

It wasn’t mountaineering’s first disagreement, but it was one of the most widely publicized. Ultimately, the men abandoned their summit attempt, pushed back by wind, cold, and a treacherous approach. Tired and hungry, the whole team descended Hkakabo Razi and trekked back through the jungle for two weeks on a diet of nettle soup and rice. O’Neill returned to her family in Telluride, rail thin and depressed.

“It nearly broke me,” she says. “It was almost my retirement trip.”

If this had been O’Neill’s final expedition, it would have capped an impressive career. The 42-year-old is the first woman to have climbed both Everest and neighboring 27,940-foot Lhotse in 24 hours. (She did it on a sprained ankle.) She skied from the summit of 26,906-foot Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth-highest mountain, without supplemental oxygen. She climbed Kilimanjaro with a broken leg. She has made first ski descents of big peaks in Mongolia, India, Russia, and Greenland.��

The youngest of three children, O’Neill started skiing at age three in Seattle. In winter, she rode the bus to local ski area Stevens Pass with her brother and sister. In summer, she traveled the Inside Passage on the family’s boat. She learned to climb between biology courses at Colorado College. After graduating, she left for Chamonix, France, where she planned to spend a winter. She stayed five years, working as a cycling guide and freeskiing on her days off. She became the European Women’s Extreme Skiing champ in 1996, but it wasn’t until she took up alpine climbing that she found her niche.��

“On my own, I think I’d be a good skier on big mountains, no big deal,” she says. “But when I combine it with climbing, the meeting of sports has definitely played in my favor.”

In 1999, O’Neill joined ski mountaineer Mark Newcomb and photographer Chris Figenshau to ski the Bubble Fun Couloir on Wyoming’s Buck Mountain, a precipitous line that ends at a 200-foot cliff. It was the first female descent, and it launched O’Neill’s career. “I really didn’t know what I was getting myself into,” she says. “It was really steep. It was a bigger deal than I knew at the time.”��

Three weeks later, the North Face put her on a plane to the Indian Himalayas for her first expedition, up 19,688-foot Deo Tibba. She started rolling through trips at a rate of three or four a year. In 2001, she became a paid North Face athlete.

“I didn’t even know this lifestyle existed,” she says. “The door was wide open for me in the beginning.”

O’Neill’s athleticism and stoicism have won the admiration of other climbers. “I have enormous respect for her,” Jenkins says. “She’s the toughest woman I’ve ever met.”

“She’s got presence, charisma, confidence, and she’s incredibly strong” says mountaineer Conrad Anker. “Just getting to the base of that mountain in Myanmar was an incredible feat.”��

It took O’Neill months to get over the Hkakabo Razi ordeal. The mental and physical aspects were exhausting enough, but she also felt that Jenkins had publicly vilified her in one of his posts. (O’Neill of the climb for the North Face’s website, leaving out the group dynamics.)

To recover back in Telluride, she skied, hiked, and spent time with her husband, Brian, a realtor and an accomplished skier, and their two sons—Quinn, eight, and Grayden, six. She has considered scaling back her mountaineering trips to be with her family more often. “It’s hard to return from an expedition to that day-to-day humdrum of life, having to pay bills, go grocery shopping, and clean toilets,” she says.

It affects her relationship with her family, too. Brian looks after the boys while she’s gone, and she sometimes envies their closeness. “I feel like an alien when I come home,” she says, “like a stranger in the house stepping into the routine and getting in the way.”

Sometimes she imagines finding another sport—endurance running, say—that she can do during the day and still coach her boys’ soccer games in the evening.

But O’Neill isn’t very good at scaling back. When Quinn was ten months old, she left for a two-month expedition to attempt the first female ski descent of Gasherbrum II in Pakistan. (Conditions forced her to turn around at 24,600 feet.) “I look back now and think, Wow, that was probably a little aggressive,” O’Neill says, although she notes that male climbers with kids are rarely questioned about the risks they take.��

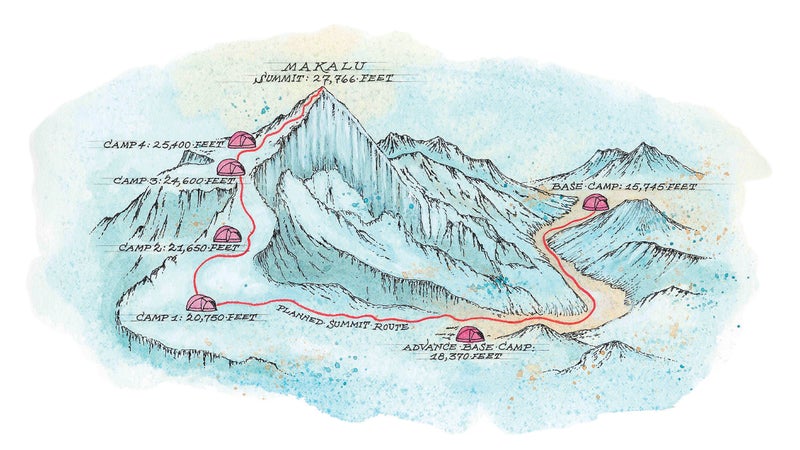

When the opportunity arose to join Harrington and her boyfriend, mountaineering guide , in attempting the first ski descent of Makalu, the world’s fifth-highest peak, O’Neill signed on.��

She also decided to incorporate some family time into the expedition—this year, Brian and the boys will join her on the ten-day trek to Makalu base camp in August. (Teacher: “What did you do on your summer vacation?” O’Neill boys: “Trekked to Makalu so Mom could make the first ski descent.”)

O’Neill will then climb with Ballinger, Harrington, and pro skiers Jim Morrison and Kit DesLauriers, the first person to ski the Seven Summits. Makalu is one of the Himalayas’ most difficult peaks, with steep ice and a technical rock ridge before the summit. “It’s a beautiful mountain,” O’Neill says. “My goal is to climb it without oxygen. But it’s a much harder climb than Cho Oyu, and I’m ten years older.”��

Whether she’s successful is secondary to the effort itself. “I have this intense fear of every day being the same,” O’Neill says. “Mountaineering gives me a way to keep my life somewhat uncomfortable.” ���� ��

The Making of a First Descent

At 27,766 feet, and with several technical sections, Makalu is one of the most demanding climbs in the Himalayas. Here's how the team plans to do it.

Woman Versus Mountain

Few expeditions have ventured to the world’s fifth-highest peak, but O’Neill has been working toward this for a long time.��

MAKALU

May 1955: Frenchmen Jean Couzy and Lionel Terray summit via the north col.

May 1977: An American team fails to climb the mountain via the west face.

May 1990: American Kitty Calhoun is the first woman to summit.

May 1997: A five-member Russian team summits via the west face.

January 2006: French mountaineer Jean-Christophe Lafaille disappears while making a solo attempt at the first winter ascent.

February 2009: The first successful winter ascent is completed by Italian Simone Moro and Kazakh Denis Urubko.

��’N��������

December 1972: Born in Seattle.

March 1996: Wins the European Women’s Extreme Skiing Champion, Chamonix, France.

January 1999: Makes first female ski descent of Bubble Fun Couloir, on Wyoming’s Buck Mountain.

May 2002: Completes the first ski descent of all five Holy Peaks in Mongolia’s Altai range.

October 2005: Skis from the summit of Cho Oyu without supplemental oxygen.

May 2012: Becomes the first woman to climb two 8,000-meter peaks—Everest and Lhotse—in 24 hours.