EVERY year on Mount Everest seems to generate a milestone of one sort or another, however dubious. The 2007 climbing season that just wrapped up saw the first use of a Ping-Pong table at Base Camp and the first summit attempt by a climber with no arms. But even by these standards, the season of 2006 was weirdly memorable for two reasons that, thanks to the ruthless symmetry between triumph and catastrophe in high-altitude mountaineering, neatly canceled each other out. A total of 480 climbers reached the summit of the world’s highest peak: a remarkable figure (the largest number to top out in a single season) and one whose symbolic import was surpassed only by the size of the butcher’s bill.

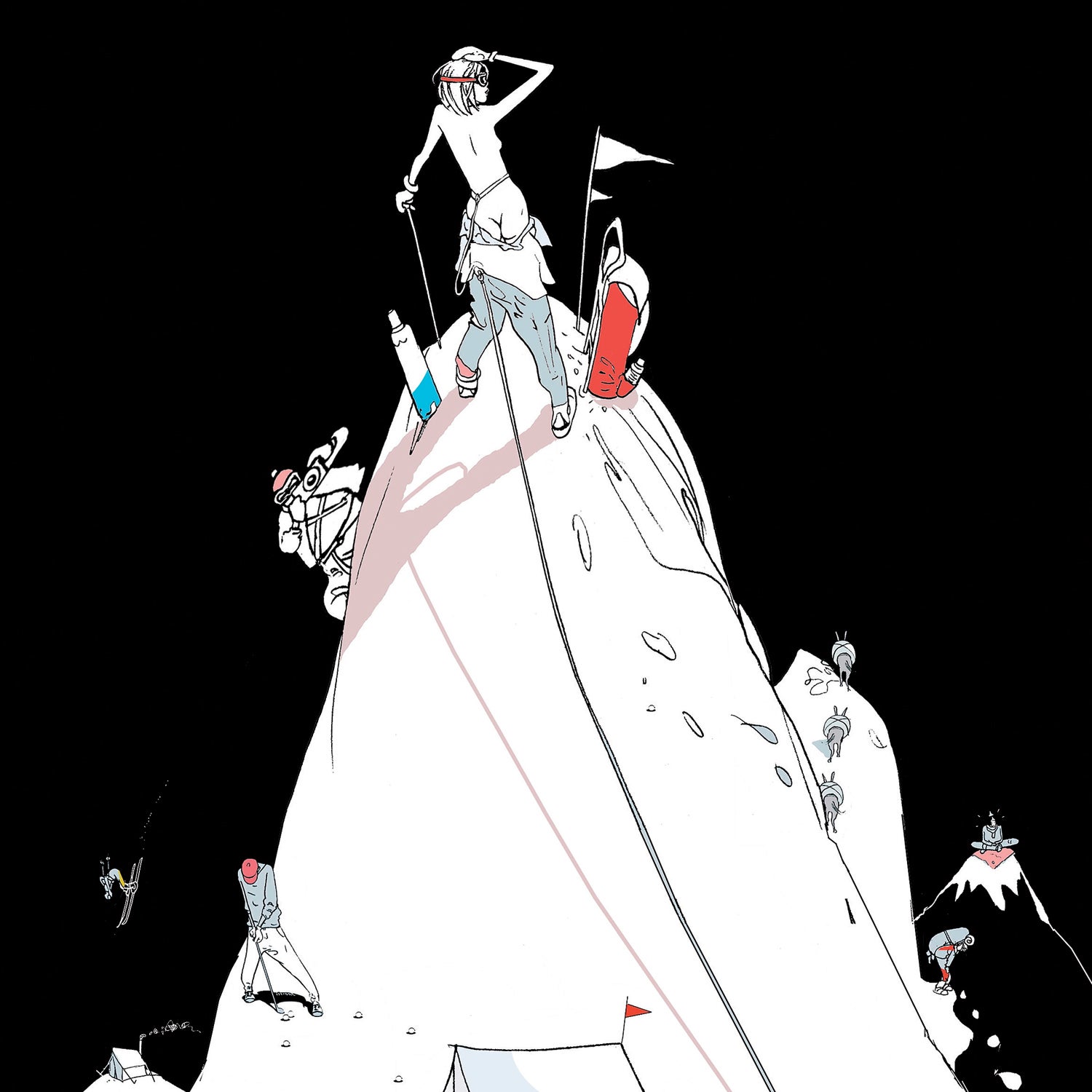

Party at Everest Base Camp

Party at Everest Base Camp

Party at Everest Base Camp

By the final week of May 2006, two climbers had plummeted to their deaths, three had succumbed to pulmonary or cerebral edema, another had died of exposure, two had fallen prey to exhaustion, and three had been buried alive by a collapsing serac. Most of those fatalities had taken place inside Tibet on the north side of Everest, a world utterly cut off from the mountain’s more familiar south side. But thanks to the Internet, news of these incidents had reached south-side Base Camp in Nepal. There, on the morning of May 24, photographer Peter McBride and I were sitting in our mess tent with Kami Tenzing, a sad-eyed and enormously capable Sherpa in his forties who served as our guide and translator.

As the three of us morbidly pondered the fact that 11 deaths had just made 2006 the second-worst season ever, we were half-listening to chatter filtering down from the summit on Kami’s radio congratulatory whoops announcing the final top-outs of the season. Kami had dialed to a channel used by New Zealand based ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Consultants, one of the largest commercial expeditions on the south side, when a young climbing Sherpa named Lakpa Tharke broke in to announce that he had an important message for his boss, Ang Tsering, the company’s head Sherpa, or sardar. Given the dark juju in the air, we braced for the worst.

“Ang Tsering, sir,” crackled a voice coming down from 29,035 feet. “Could you please inform our liaison officer that Lakpa Tharke, 25, from the village of Phortse, has just posed naked on the summit for five minutes?”

“This is a really bad idea,” Kami said after translating the remarks into English. From the other side of Base Camp, Ang Tsering keyed his radio and replied, “Five minutes? Naked? Impossible!”

His skepticism was swiftly echoed as Sherpas all over the mountain began transmitting their own opinions.

Five minutes?

Bullshit.

One minute, OK. Two, maybe. But five? No way!

Hearing the disbelief, Lakpa Tharke rose to defend himself. “I have three photographs,” he shouted. “That’s got to be at least three minutes, yes?”

Three? Mmm.

Well, who can say? Perhaps this might be possible

Stupid, yes, but possible.

“Oh, and please be sure to note,” Tharke added, “I am not doing this for the record. I am doing it for world peace.”

“What the fuck?” Kami exclaimed. “He could be doing this as a temperature experiment, a stunt, a personal statement. But world peace? He could have said anything other than that.”

“Hey, Kami,” I interjected, “this business of being naked on the summit would that be considered an offense to the gods of Everest?”

“Oh, how the hell should I know?” Kami barked, one of the few signs of exasperation he’d let slip in the 25 days we’d been together.

“Look around you,” he continued, waving his arm in a sweeping arc that seemed to encompass not only Base Camp and the mountain looming above it but all the events silly, heroic, tragic, and farcical that had unfolded in this surreal outpost during the previous month.

“People come up here and they feel like they can do whatever they like,” he declared. “What else do you want me to say? I have no idea what to think about anything anymore. Everybody here is completely insane.”

IT’S NO SECRET that during the past decade or so, Everest has become an experimental theater for the sort of behavior that any self-respecting alpinist finds repugnant and 2006 offered as vivid a reminder of this as you’d ever want to see. The 45 expeditions on both the south and north sides included a pair of Bahrainians hell-bent on setting a new world record for the fastest ascent of the mountain (this despite having no previous high-altitude-climbing experience whatsoever); a 62-year-old Frenchman who’d had a kidney removed just prior to leaving for Nepal; a young British climber who perished next to the north side’s main climbing route after reportedly being passed by more than 40 people; and a stricken Australian who was abandoned high on the North Col and later rescued but only after his guide had descended safely and telephoned the man’s wife to tell her the false news of her husband’s death.

Those stories underscored the notion that, on the tenth anniversary of what is still the most notorious disaster in Everest history the storm of May 10, 1996, which claimed the lives of eight people in 24 hours things were more out of control than ever. And as the climbing world once again took note of the self-indulgent grandstanding and pointless absurdity of it all, a fresh wave of outrage poured forth from mountaineering deacons like Sir Edmund Hillary, who told reporters in New Zealand that “the whole attitude towards climbing Mount Everest has become rather horrifying people just want to get to the top; they don’t give a damn for anybody else who may be in distress.”

When McBride and I left for Nepal, of course, most of these events had yet to unfold. Our arrival at Base Camp on May 9 coincided with the lull that settles in just before the summit rush. The Sherpas who perform the grunt work that enables commercial clients to ascend the mountain had already prepared the four camps along the South Col route hauling up tons of food and bottled oxygen and rigging miles of ladders and fixed rope. By then, almost every client had completed several acclimatization trips to Camps II and III (at 21,000 and 23,500 feet, respectively), and several of the more opulent expeditions had even taken helicopter rides back to Kathmandu to enjoy a “recovery break,” which involved splashing in the pool and playing roulette at the Hyatt Regency before returning for their summit bids. This meant that more than 500 jittery climbers and jaded Sherpas were now sitting in Base Camp with nothing better to do than drink, gab, and wait for a 72-hour window of clear weather so the summit assaults could start.

It seemed like the perfect time for McBride and me to start cataloging the excesses that, supposedly, had corrupted the world’s noblest mountain beyond any hope of redemption. Having dutifully done so, I am now able to report that, during the following three weeks, we witnessed a number of things that merited Very Deep Concern. However, we also discovered something that’s often lost on those who rush to condemn the Everest circus but that is gloriously evident to the intrepid tribe of fit, motivated people who come from all over the world each year to partake in this Himalayan version of Burning Man.

Namely: In addition to presenting a rather grotesque perversion of pretty much everything that alpinism is supposed to represent, Everest Base Camp also happens to beÔÇöand I’m afraid there’s just no other way to put thisÔÇöan absolute fricking blast.

IT TAKES EIGHT days to get from the Nepalese village of Lukla to the foot of Everest. You know you’ve arrived when the trail slams up against a soaring atrium of ice-enameled rock that serves as a kind of Maginot Line separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. From this spot, you can see the tops of five world-class leviathans: Khumbutse, Nuptse, Lhotse, Pumori, and Lingtren. Everest is here, too, but its summit is invisible, tucked behind the mountain’s West Ridge. After a moment, your gaze peels away from the imperial-looking ridgelines and the cobalt-colored sky and tumbles down the mountain to the disheveled surface of the Khumbu Glacier, where roughly 11 bajillion tons of rubble are convulsing beneath your feet, emitting a grunting chorus of odd pops, ominous hisses, and digestive gurgles.

It’s a weirdly unstable platform. Every couple of hours a new fissure winks open or another humpbacked stone slides into a pool of meltwater with a blooping splash, like a walrus returning to the sea. And thanks to all that restless heaving, it’s the last place you’d expect to find, say, a small city. Yet as McBride and I could see, somebody had obviously decided it was the perfect spot to stage an entire Renaissance Faire.

Prayer flags streamed in all directions, snapping crisply in the hypoxic breeze at 17,600 feet. Beneath those flags sprawled an alpine metropolis of more than a thousand people crammed into some 250 tents that had been stocked with 3,000 yakloads of gear, food, and medical equipment (and which required a resupply of 200 additional yakloads every two weeks). The 27 expeditions spread along this half-mile strip had turned the place into a cross between a Central Asian bazaar and a pre-Christmas PlayStation sale at Wal-Mart. While cooks bartered everything from flashlight batteries to maple syrup, porters clad in shower sandals staggered beneath gargantuan loads of climbing rope, whiskey, and aluminum ladders. Crampon-clinking Sherpas mingled with windburned climbers, shuffling trains of exhausted yaks, officious-looking liaison officers from the Nepal Ministry of Tourism, and nappy-coated pack ponies whose saddle bells jingled merrily in the frost-chilled air.

This, we soon realized, was more than simply the world’s most rarefied ghetto of dirtbags. It was a United Nations of mountaineering whose members had cordoned themselves into boroughs, each boasting its own special zoning codes and municipal traffic patterns.

To put distance between themselves and the trails plied by the odoriferous yak caravans, the bulk of the five-star, commercially guided expeditionsÔÇöwhich generally charge clients between $30,000 and $65,000 a popÔÇöhad clustered on the east and west sides of the moraine. This zone was populated by huge outfits in which dozens of climbing Sherpas and guides served up to 30 clients per group. They included ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Consultants, an American company called International Mountain Guides (IMG), and two crews operating under the umbrella of Henry Todd, the controversial Scotsman known as “the Toddfather,” who supplies much of the bottled oxygen on the mountain (and who spent nearly eight years in prison during the 1970s for distributing LSD in London).

Luxuristan, as we dubbed it, featured the densest concentration of massage tents, solar-powered showers, padded toilet seats, Internet-caf├ę services, and plastic-flower bouquets in all of Base CampÔÇöamenities that the managers of these camps found mildly embarrassing, but in a pleasantly resigned kind of way.

“Yeah, Everest is a bizarre place,” shrugged one team leader who half-jokingly allowed that the only qualification his company imposed on prospective clients was that their checks didn’t bounce. “A lot of people really don’t belong up here because, let’s face it, this is one of those places where you actually can buy your way in.”

At the top of Luxuristan’s pyramid was a special expedition run by Mountain Link, an American firm with about a dozen Sherpas, seven guides, a $400,000 budget, and only one client. Chris Balsiger was a sandy-haired, 54-year-old multi-millionaire from El Paso who was hoping to polish off the final piece in his Seven Summits campaign. Balsiger and his entourage enjoyed elaborate meals prepared by a chef who’d brought in 38 coolers stuffed with fresh vegetables, jars of salad dressing, and steaks. The Team Texas communications tent was equally impressive: Its solar-charged grid powered an array of sat phones, camcorders, laptops, and satellite uplinks that enabled team members to update their Web sites each day with podcasts and video footage. The tents also contained a film library with 60 DVDs, which the Texans generously shared with McBride and me.

I later reported these details back to Kami Tenzing, who gave a knowing nod. “Fifteen years ago, Base Camp was a different place,” he said. “Our only communication with the outside world was through the mail runners, who would walk all the way to Kathmandu and back. But now we have kerosene heaters, videos, and e-mail. And the type of clients who come to the mountain today are much more sensitive. We call them the Butter People.”

“The what?”

“Mar ke mi. It means butter person’ in Sherpa. It refers to people who are very pale, and who are always rushing to put on all their clothing the instant that they get cold. But then the minute they get hot, they are rushing to take all their clothes off again.”

“Basically, they’re soft,” he concluded, “and they tend to melt easily.”

THE BUTTER PEOPLE embodied the Everest excess that we all find so deliciously loathsome, so during the next few days McBride and I kept sneaking over to the Texas camp hoping to gather more dirt. Whenever we showed up, however, they wound up doing something nice, like feeding us eggs Benedict or insisting we join them for yet another movie. In the end, their generosity and decency made it impossible to hate them although the other commercial juggernauts of Luxuristan provoked plenty of rancor, especially among the smaller private groups who were having a harder time of things.

One of the most beleaguered parties was a two-man Czech team. It consisted of an experienced mountaineer with an intense gaze named Martin Minarik who, together with his friend Pavel Kalny, had launched an ascent of 27,940-foot Lhotse without any guides or climbing Sherpas. On May 9, after becoming disoriented and exhausted, Kalny took a fatal fall on the Lhotse Face. Having already forged ahead to prepare tea in Camp IV, Minarik failed to witness the accident. Kalny was found the next day by a group of Chilean climbers who remained with him until he died. His body was then placed in a sleeping bag, and Minarik retreated to Base Camp, where he discovered that his nightmare was just beginning.

Word of the incident had already reached Paul Adler, an Australian client with IMG who was running his own Everest blog. In violation of IMG’s policy, Adler fired off an unconfirmed “report,” preempting an official announcement by the Nepal Ministry of Tourism, stating that one of the Czechs was dead, without saying who. This threw both climbers’ families into a frenzy.

At the same time, having suffered such severe frostbite while searching for his partner that he could no longer walk, Minarik started asking the big commercial expeditions if they would order their climbing Sherpas to retrieve his friend’s body. But no one was keen to divert vital resources on the threshold of their own summit pushes. And, in any case, Minarik was either unwilling or unable to fork over the total of $2,000 that the Sherpas would have charged. When I paid a visit to his tent one evening, he lashed out in fury.

“Oh, these fucking commercial expeditions,” he fumed, pounding the air with his fists while his blackened toes marinated in a pan of lukewarm water. “They are so busy getting caviar and champagne up to Camp II, they can’t even bring themselves to help a fellow human being. It’s disgusting!” Minarik’s rage evoked both sympathy and exasperation throughout Base Camp’s second-biggest neighborhood, Schmoozistan a hodgepodge of less affluent non-commercial expeditions whose members were devoting most of their pre-summit time to paying social calls on one another. Setting foot anywhere inside this cheerful district, regardless of the hour, triggered a burst of hearty salutations ÔÇö”Bongiorno!” “Dobryi den!” “Yo, dude Whassup?”ÔÇöalong with a nonrefusable invitation to drop inside for a toast.

Although Schmoozistan’s arrangements were more spartan than those of Luxuristan, each encampment took special pride in doing one thing better than the others. The Swiss had the most accurate weather reports. The Spaniards brewed the tastiest cappuccino. The Filipinos boasted the most impressive communications setup a satellite dish brought in by yak and powered by a 360-pound generator airlifted to Base Camp in a Russian helicopter. And the Indians offered up the best spiritual counseling. (Their leader, Brigadier General Sharab Chandub Negi, delivered elaborate sermons on the benefits of pranayama yogic breathing and Buddhist meditation.)

Schmoozistan’s eclectic cast also included the legendary Italian alpinist Simone Moro, 39, a balding and sinewy figure who was hoping to complete Everest’s first solo south-to-north traverse from Nepal to Tibet; a grimly obsessed 40-year-old Indian lawyer named Kalpana Dash who was making her third Everest attempt; and Toshiko Ushida, a 75-year-old Japanese woman with a warm smile who was intent on becoming the oldest person ever to summit. Rounding out the mix were teams from Mongolia, Turkey, and South Africa, plus three expeditions from South Korea.

Once you made it through the hospitality gantlet to Schmoozistan’s southwestern border, you crossed into Inebria. This cluster of mold-coated canvas tents was home to four ragged Sherpas who built and maintained the climbing route through the ever-shifting labyrinth of the Khumbu Icefall, the biggest graveyard on Everest. The Ice Doctors, as they’re known, had one of the most dangerous jobs on the mountain. And when they weren’t on duty, they loved to sit in front of their tents bathing in the sun and pounding whatever alcoholic libations they could get their hands on.

A stone’s throw away from Inebria sat the tiny municipality of Bunnystan a group of tents sheltering a team led by National Geographic Poland editor Martyna Wojciechowska, who appeared in Polish Playboy’s June 2001 issue and was hoping to become the first Bunny to stand on top of the world. Martyna was Base Camp’s favorite topic of gossip, and everyone delighted in trading apocryphal tales about her cosmetics, her narcissism, and the rude manner in which she supposedly treated her Sherpas.

“I’ve never actually hoped that somebody wouldn’t get to the summit,” remarked an American climber who, like most people peddling anecdotes about the so-called Energizer Bunny, had yet to even speak to her. “But I’ve heard so many horrible stories about the woman, I really hope she doesn’t make it.” Finally, there was the little patch of blackened mud and half-frozen yak dung that Kami Tenzing had reserved for McBride and me. We christened the place Bewilderabad.

BEFORE COMING to Base Camp, I’d been warned that interlopers who weren’t there to conquer the mountain were often treated with hostility. Yet among the many hospitalities of Luxuristan, Schmoozistan, Bunnystan, and Inebria, we never encountered the unpleasantness we’d heard so much about.

“You know what I just realized?” McBride said to me one afternoon toward the end of our first week. “I love this place!”

And who wouldn’t? Despite the frictions and tragedies, most folks bent over backwards to behave decently a state of affairs that, given the combustible mix of nationalities and ambitions, we and others found quite remarkable.

“Like everybody else, I’d read Into Thin Air and thought this place must be an absolute shit hole,” said Dr. Luanne Freer, Yellowstone National Park’s medical director and the head of Base Camp’s medical clinic. “It’s a weird little place, but it turns out that climbers are pretty fascinating people. And, besides, it’s really fun!”

Indeed it was, often in unexpected ways. Each morning, a special squadron of Nepalese workers fanned out to service the buckets beneath the toilet tents. Known as the Poop Doctors, they charged $1.05 per pound to gather up all the human excrement in camp (around 66 pounds per day). Whenever these men dropped by, the climbing Sherpas sounded off with a little song that went like so:

“Ah mo-mo, kekpa kelugkimi!”

Rough translation: “Holy shit, here come the Poop Doctors!”

Another important institution was the daily baseball game, which started around 4 p.m. and was played on a patch of ice that doubled as the Khumbu Klassic Golf Course. Base Camp also had its own mascot, a mutt named Shipton the Superdog. In late April, Shipton made canine history by undertaking an Incredible Journey through the Icefall to Camp II, where he allegedly stole 31 hard-boiled eggs from the IMG cook tent, then dug up a human skull somewhere out on the Western Cwm.

The only thing lacking in Base Camp was the kind of Club Med style tent hopping that had prevailed two years earlier, when there were 17 women on the mountain and, recalls Dr. Luanne, all eight of the pregnancy-test kits she’d brought with her got used up during the season. Nobody seemed to know why, but the buzz about 2006 was that romance was clearly down.

“Some years, it can be a real sausage-fest up here,” sighed one frustrated male expedition leader. “All I’m doing this season is sleeping in the dirt by myself.”

If Base Camp had a town center, it was the Himalayan Rescue Association’s medical center, run by Dr. Luanne and her assistant, a jolly emergency-room physician from Idaho named Eric Johnson. Dr. Luanne had started this service three years earlier, inspired by Tashi Tenzing, Tenzing Norgay’s grandson, and it was a huge hit. In addition to patients, the clinic hosted a three-man BBC film crew shooting a documentary called Everest E.R. The BBC guys spent their days lounging on a thick piece of blue ensolite strewn with girlie magazines that always drew an appreciative crowd of Sherpas. The ensolite got warm in the sun, so it was known throughout camp as the Beach.

The best time to visit the clinic was 5 p.m., when Dr. Luanne closed shop, the Beach was rolled up, and everybody ducked into the HRA mess tent for a popcorn-and-cocktails gossip session. I dropped by one wind-whipped evening just after the generator for the Philippine satellite dish had been delivered a breach of a long-standing tradition that restricted helicopter landings to medical emergencies.

“At the rate things are going up here,” Dr. Eric joked as he sipped on a Bombay Sapphire martini, “pretty soon people will go on supplemental oxygen day and night, starting at Shangboche [a village and landing strip at 12,000 feet], and never even have to acclimatize. I bet we’ll eventually see snow-machine shuttles and oxygenated suits up on the Western Cwm. And with all that nonsense, you know what? This place will still draw folks.”

“Really?” said Dr. Luanne.

“Absolutely,” he said. “The lure the drive of the world’s highest mountain is irresistible. People just can’t get enough of this place.”

TWO HOURS AFTER lunch on the brilliantly clear afternoon of May 17, cheers erupted on the edge of Schmoozistan. A British commercial team had just become the first of the season to tag the top from the south side. The Brits were followed by a group of South Koreans, a group of Filipinos, and a Swiss climber named Benedikt Arnold. This signaled the start of the spring summit frenzy. Up on the South Col, more than 100 climbers were primed to launch their final assaults, starting around midnight.

First thing the next morning, McBride and I strolled over to Bunnystan to see how Martyna Wojciechowska’s summit bid, which was supposed to happen any moment now, was coming along.

Bunnystan’s communications tent was run by Wojciech Trzcionka, a funny and mildly deranged reporter for a Polish newspaper who’d had such a great time at Base Camp that he was already scheming to return the following year to open up a hyperbaric oxygen bar. (After repeated failures at pronouncing his name, McBride and I simply called him Vortex.)

We arrived just as Vortex and Patrycja Jonetzko, a Polish physician with short blond hair and blue eyes, were belting out their national anthem to celebrate a minor miracle: Not only had the team summited, but they’d done so on the birthday of the late Polish pope, John Paul II.

“This is so exciting,” yelled Vortex, “that I’ve decided to smoke my last cigarette!”

Vortex’s radio was transmitting a blizzard of excited Polish chatter. Patrycja said the entire team was now on the summit, and that Vortex was speaking with Martyna’s teammate Tomasz Kobielski.

“So what are they saying?” I asked.

“Believe me, it’s not worth translating,” replied Patrycja. “Just a lot of bullshit.”

“Oh, c’mon, what are they saying?”

“Well, Tomasz is saying it feels very strange because they can’t go any higher, and Wojciech is telling him that they need to initiate their descent because there are some girls down here waiting for him in the bathtub.”

“Bathtub?”

“And now Tomasz is saying that they’re going to get the fuck off the fucking summit and come the fuck down.”

While talking to Tomasz, Vortex had been surfing the Internet, where he’d just discovered a report that Tomas Olsson, a Swedish climber on the north side, had fallen more than 5,000 feet to his death after a rappel anchor broke loose.

“This is really quite surreal,” observed Patrycja. “On the one hand, you have all these people celebrating. On the other hand, all these other people are dying.”

Vortex, meanwhile, had switched over to a Polish news site and uncovered another disturbing piece of information. Apparently, the Polish Everest team would be returning home on the very day that JP2’s successor, Pope Benedict XVI, was scheduled to arrive on his first visit to Poland an event almost certain to upstage the press conference Vortex had set up to trumpet the world’s first Playboy Bunny summit.

“This is terrible!” Vortex exclaimed, slapping his forehead.

“You have to understand,” Patrycja told me, “that in Poland everythingÔÇöeven EverestÔÇösomehow always relates back to the pope.”

“Pasang!” cried Vortex, addressing his Sherpa sardar through the walls of the tent. “Do you have a cigarette? I need another cigarette immediately!”

THE WEATHER REMAINED stable and clear, and over the next few days the Spaniards, the Indians, and all the big commercial teams began putting climber after climber on top. Meanwhile, weird things were happening lower on the mountain.

At Camp II, Kalpana Dash, the Indian woman, had run out of steam and announced that, since she couldn’t summit, she would fling herself into a crevasse forcing her Sherpas to tie her into a special safety harness. Around the same time, Toshiko Ushida, the elderly Japanese woman, had bonked as well, and during her descent she’d taken so long to get through the Icefall that her Sherpa had reportedly considered flinging himself into a crevasse. And Chris Balsiger, the Texas millionaire, had stalled out just above Camp III.

“What a way to spend a million bucks, huh?” he quipped later, keeping a sense of humor about it. “But what else was I gonna do buy myself another boat?”

The mood was bleaker over at the Czech camp, where the frostbitten Martin Minarik had struck out in his efforts to retrieve the body of Pavel Kalny. Simone Moro, the Italian superclimber, had volunteered to lower Kalny into a crevasse during his solo traverse. But for some unknown reason, that hadn’t happened and now Moro was on the north side, apparently trying to argue his way out of a $50,000 fine for having crossed into Tibet without a Chinese climbing permit or visa.

Finally, Minarik had taken his problem to the people who probably should have volunteered to solve it in the first place. The South Korean Han Wang-Yong Cleaning Expedition was supposed to be collecting five tons of refuse, which mainly meant oxygen bottles and, alas, dead bodies. According to Minarik, the South Koreans had promised to bring Kalny down but then mysteriously withdrew their offer. On May 21, Minarik finally threw in the towel and left, cursing the cruelty of Base Camp from the back of a Nepalese porter who was literally carrying him. As a final insult, Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism later refused to refund his $3,000 “garbage-disposal deposit” because he’d left his friend’s body behind.

Later that afternoon, word arrived that the Polish cover girl had come down from the summit and was available to talk. I raced over to Bunnystan, where I was greeted by a willowy brunette who looked like she was having a bad-hair month and hadn’t taken a bath in 56 days.

Martyna Wojciechowska wasn’t quite as big a star in Poland as the pope, but she came pretty close. Back in the late nineties she’d hosted Auto Maniac, a TV show devoted to Formula One racing, before moving on to host Big Brother (Europe’s most popular reality show) and then starting an exotic-travel program called Mission Martyna that featured her sand-surfing in Chile and wrestling anacondas in Venezuela.

Mission Martyna was a hit until 2004, when the Energizer Bunny, while filming an episode that involved searching for elves in Iceland, suffered a car accident that killed her cameraman and shattered her spine. Doctors said her adventure days were over and told her she had to start “living like a normal person.” At which point she decided to climb Everest.

“I had to fight my way back,” she told me. “And the best way was to prove it’s possible for somebody who is not a climber to get to the top of the world’s highest mountain.”

“So how was the summit?” I asked.

“Well, initially it was very foggy, but then the fog lifted to reveal a beautiful view of Tibet. Mountains upon mountains enough to make you think the whole world is made of them. But it was so crowded up there. There was this Korean group, and they were all shouting and using their sat phones, and I couldn’t even hear my own thoughts!”

“What did you do in the midst of all that ruckus?”

“Well, I made some calls of my own. I had a live satellite connection with TVN2 which is the Polish CNN and with my mom, and with my boyfriend, Chris, who is a safari guide in Africa, and who had proposed to me a few days earlier. I must say, however, the summit was not what I expected.

“It was actually kind of a shabby moment,” she continued, “fighting to have a moment of beauty to yourself. You know, after my accident, I had thought that standing on top of Mount Everest would make me the happiest person on earth. But now I know this is simply not true. And suddenly it seemed like maybe it wasn’t so important after all.”

DURING THE FINAL WEEKS of May, the north side turned into a high-altitude morgue. Two days before Tomas Olsson’s fatal fall on May 16, an Indian climber named Constable Sri Kishan had toppled off the Second Step. A day later, David Sharp, the young mountaineer from Britain who’d been passed repeatedly as he huddled alongside the main climbing route, froze to death. On May 17, French climber Jacques-Hughes Letrange died from unknown causes. Two days after that, the Brazilian climber Vitor Negrete expired in his tent, probably from pulmonary edema. On May 22, Russian mountaineer Igor Plyushkin died in circumstances similar to Negrete’s. And the last fatality of the season took place on May 25, when Thomas Weber, a semi-blind German climber, succumbed to exhaustion.

By this point, there was still a handful of teams tagging the summit from the south side, but the cheering was getting drowned out by the yells of porters dismantling tents, packing goods, and reversing the massive flow of luggage downvalley.

Meanwhile, Kalpana Dash, the suicidal Indian lawyer who had been safely escorted back to Base Camp, was crying inconsolably in her tent. She blamed her third failed summit try on her Sherpas for forcing her to descend, and she’d decided to file a formal complaint against them the moment she reached Kathmandu.

I dropped by to ask why it mattered so much, given that she was still alive.

“Why?” she wailed. “Because Everest is my life it is my life! The summit of Everest is my dream. It is everything to me!”

Dash wasn’t the only one upset. Two days earlier, the South Korean cleaning expedition had, with fanfare, swept through Inebria and Bewilderabad toting garbage bags and a video camera but somehow managed to miss a burlap sack and two ancient pairs of underwear lying in the rocks beside our cook tent.

“Tell me, is this cleaning or not?” fumed Kami Tenzing, who clearly had reached the limit of his tolerance for Base Camp high jinks. “You know what they will do now? They will go to the media and report that they have taken hundreds of kilos of garbage down from Everest. In their country and in the eyes of the world, they will be heroes. But look at this shit! I hate these cleaning expedition guysÔÇöit’s such a scam, what they do!”

Then Kami’s anger took a sharp, unexpected turn. “So many Western climbers achieve fame on Everest with the help of us Sherpas,” he said. “But almost none of them ever give anything back.”

“Oh?”

“Every movie or story I have ever seen about Everest focuses only on the Western climbersÔÇöthere is never any depiction of the Sherpas. I know it’s not necessary, but I wish they gave some credit for how hard we work, how heavy our loads are, how many times we go up and down, breaking trail between the South Col and the summit, or fixing the route on the Lhotse Face, and for the risks we take in doing these things. But they never do the Sherpas are always the hidden story. You don’t have to show everything, of course. But there should be some small credit given, no? Even just showing our faces? It’s true that we are working for you and that you are paying us. But it’s almost like we are slaves.”

Later, McBride and I ran these comments past Rodrigo Jordan, the leader of the Chilean expedition and the man who had found Pavel Kalny before he died. Jordan was one of the smartest guys in Base Camp, and he nodded emphatically when I told him about Kami’s remarks.

“They’re paid for what they do, so they’re not really slaves,” he said. “But the commercial clients up here aren’t mountaineers either, at least not real ones. Those that make it to the summit will unfurl their flags and take their photographs, and then the average American or German or Japanese who reads about it in the newspaper will never understand that 90 percent of the work was done entirely by the Sherpas. It’s not exactly a secret, but people don’t go out of their way to advertise this fact, either. So, yes, sometimes these men become very upset. And if you were one of them, you’d probably be pissed, too.”

ON MAY 25, McBride and I decided it was time to hit the trail, and it occurred to me that some of the finest moments in Base Camp were days like this. Each night, all the prayer flags froze, and in the morning, when the sun’s first rays hit these bright little squares of cloth, the ice crystals inside would evaporate and little puffs of steam would waft into the air in a way that made the flags look like they were breathing. Then the light would hit the Khumbu Icefall and start bouncing among the seracs, shimmering and coruscating until that entire jagged mass of blue ice seemed to levitate on the iridescent force of its own beauty. Base Camp seemed like a notch below paradise at such moments, and I recalled something the Energizer Bunny had said.

“Everything is so concentrated up here,” she’d told me. “Survival and death, suffering and happiness, ambition and humility. During these two months in Base Camp, you sometimes feel as if you’ve lived an entire lifetime in this placeÔÇödon’t you agree?”

I did. Because, more than any other feature on Everest, Base Camp seemed to offer up a set of ideas that suggested, at least to me, that Sir Edmund Hillary’s condemnation of what this mountain has become might be profoundly mistaken.

First, there was the notion that every person connected with the placeÔÇöthe Ice Doctors and Poop Doctors, the Butter People and “slaves”ÔÇöwas both a hero and a victim in a drama of his own making, and that the hunk of rock at the center of that drama neither ennobled nor diminished those attempting to climb it but instead was simply there. And because it’s there, looming along the outer edges of human physiology and imagination, Everest had somehow distilled the essence of those drawn into its orbit their courage and ludicrousness, their foibles and fears and reflected those qualities back in ways that were both stark and urgently compelling.

Most climbers probably knew this already or learned it on the mountain. Because you simply can’t return from the most exalted place on earth without acknowledging your bottomless frailty, your utter insignificance, and the awkward fact that your life represents a bestowal of grace that you’ve done nothing to deserve. Nor can you fail to consider the prospect that one reason maybe the reason why the world, despite its many desolations and depravities, sometimes vibrates with such harrowing beauty is that horror and levity might be linked inside the human heart in the same ineffably mysterious way as sadness and love.

Finally, there’s the notion that these things may balance on a blasphemous paradox: the possibility that the act of climbing Everest might be rather superfluous. Because the most bewitching feature of the world’s highest peak may not, in fact, be located anywhere near the top. Instead, it may be folded into the absurd, oddly redemptive chaos of Base Camp right down at the bottom of it all.

Which, in the end, is where the most interesting forms of truth abide. Don’t you agree?