REAL ALPINISTS KNOW HOW TO SLEEP. The night before a big climb I’m sure they eat heartily—slabs of bratwurst and chunks of stinky cheese—put away a bottle of robust red wine, crawl under any old wool blanket on the bunk, and fall asleep as contented as a Saint Bernard.

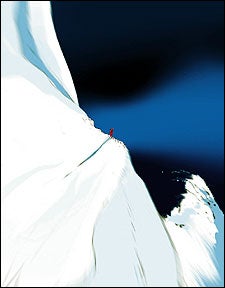

Illustration by Istvan Banyai

Illustration by Istvan Banyai

Not me, dammit. Here I am, alone in the Empress Hut, a breathtaking aerie perched above gigantic glaciers at the base of 12,349-foot Mount Cook, the highest peak in New Zealand, and the moment my lids drop over my snow-burned eyeballs, my mind’s eye clicks open like the lens of a camera. I see the notorious Sheila Face, certainly named by some carnal-dreaming mountaineer, looming like a succubus above the hut. I find the lightning bolt of ice that jags through the stygian stone. I follow the streak up the face, trying sleepily to discern the difficulties of every pitch. At the final 300-foot headwall of ice, I study its color and wonder if it will be hollow or mushy and suddenly see my ice tools plunging into depths of sugar and my feet slipping and my body cartwheeling into space.

See what I mean?

I used to have a climbing partner who could cheerfully fall asleep anywhere, anytime. No sleeping bag, no problem: “This spot right here looks pretty darn good to me,” he’d say, and then proceed to lie down on a six-inch snow shelf above a fathomless drop and be snoring away in less than five minutes. If only.

It’s 11:30; I must be up in five hours. I rewind the scene I witnessed earlier this evening while reconning my route: a chopper circling above the Sheila Face, lowering a cable, and plucking two climbers off the peak. According to the hut radio report, they had bivouacked for two nights on the wall, then called in a rescue after almost getting killed by falling ice and rock.

Will that be me tomorrow? Again I slip into snapshots of ugly scenarios. Rock that is verglased, coated in frozen death slime, or weather that sucker-punches me part way up and I can’t see anything in the swirling snow.

Shut up.

Real alpinists know how to turn off their head. From years of experience, they realize that half the time the body knows better than the know-it-all mind. The mind is too fickle. Optimistic one minute, pessimistic the next, pitching back and forth like a little boat on big seas. Not the body. The body doesn’t exaggerate or self-deprecate or play mind games. The body is a machine, a realist. If it’s hard and painful, well then, it’s hard and painful. If it’s a cruise, why, it’s a cruise. The body doesn’t make mountains out of anything. The body is an animal. It moves and lives in the present.

Now it’s midnight. I wearily decide that the route will decide. I promise myself not to climb up anything I can’t climb back down. I check my watch alarm for the third time. Flick my headlamp on and off. Finally drift to sleep.

Alas, one side effect of an overactive imagination is that I do not sleep without dreaming. I am a master dreamer. Tonight there is an elfin, fur-faced man in the hut. I don’t understand what he is doing here, and of course, even inside the dream, I realize this is all supposed to mean something. This grotesque codger is supposed to be Death, profound and portentous. So where’s his scythe? Still within the dream, I disavow all this Freudian hooey. The subconscious is a reckless dust devil blowing about random pieces of a puzzle.

I wake at 4:25 a.m., just before the alarm goes off. Take a leak out the hut door, pick up the pot of milk I mixed from powder the night before, gulp down three bowls of granola. (I only feel like one, but I know better—big day ahead.) I check my ankles. They are mangled from the last five mountains. Days ago I bound them up with athletic tape and layers of foam cut from my sleeping pad.

Crampons on my boots, headlamp on my helmet. Ice ax in hand, ice hammer strapped to the pack—all by rote. I step out of the hut onto the glacier, gaze up at the stars floating like campfire sparks above the black monolith of the Sheila Face, and go.

MAYBE THIS IS A GRUDGE MATCH. Last November I came to New Zealand to climb in the Southern Alps and never even saw the mountains. It rained biblical quantities. I drove around in a dark sluice, grinding through past failures. I have returned for redemption.

From the start, I planned to climb with veteran Kiwi alpinist Guy Cotter, owner of ���ϳԹ��� Consultants, a New ZealandÐbased global mountain-guiding company. He suggested I come back at the end of January, midsummer, when the weather on the South Island might be “a wee bit more predictable.” Which I did, phoning him at his home in Wanaka from the Christchurch airport.

“Ah, mate, sorry,” he said. “I’m just about to jet off to western Papua to lead a trip on Carstensz Pyramid.”

I understood—work before play, even for a guide—but now I was on the other side of the world without a partner.

I drove straight to Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park and got a bunk in the Unwin Hut. The New Zealand hut system is wonderfully extensive, with some form of shelter in almost every major valley—from $50-a-night palatial lodges with fresh sheets and a chef to free cabins with fresh water and padded bunks.

As in the European Alps, huts make the mountain experience a social, cosmopolitan affair—in contrast to the North American search for silence and solitude. On any given evening you’re likely to be swapping stories with local trampers and climbers, as well as those from half a dozen other countries. Famously friendly, Kiwi mountaineers—some of the finest in the world—are wry, self-effacing types who inevitably downplay their most harrowing experiences: ” ‘Twas a wee bit dodgy,” they’ll say, when the smallest slip meant certain death.

There were trekkers about, but no mountaineers, so the following day, for a warm-up, I decided to climb 6,738-foot Mount Kitchener—disregarding a rainstorm that was obviously blossoming into a gale.

“You don’t want to be up there today,” warned a dour female park ranger. “At that elevation, wind’ll be 130 km/h!”

Which it was. Clambering bullheadedly up the west ridge, I got knocked flat a dozen times, as if a wet lion were leaping onto my chest. Strafing sleet stung my body like hornets. By the time I climbed off the summit and staggered into a high hut, I was so hypothermic I could hardly undress myself.

It was a humbling contretemps. Compared with other mountains in the Southern Alps, Kitchener is a mere pimple of a peak. After thawing out, wrapped in four wool blankets and sipping a tongue-scorching cup of cocoa, I wrote up the details of my baby epic—route, temperature, wind speed, how much water I drank—on the back of the topo map, as is my habit.

I don’t suppose many alpinists would have committed such a picayune ascent to paper, but I found the exercise useful. It is the simplest method I know of to imprint little lessons into the clay of one’s mind. Like: Heed the park ranger.

I’M TRAMPING UP the Sheila Glacier in the dark, following my own frozen tracks by headlamp along the route I scouted yesterday. There are two tenuous snow bridges to cat-burgle across and perhaps 20 crevasses to cautiously end-run around. With no rope and no rope mate, it is essential I do this stretch during the coldest part of the night, when the ice is at its most stable.

I reach the bergschrund in less than an hour, only to find that I’ve miscalculated. The snow is treacherously soft: I can’t cross where I’d planned. I lose an hour traversing left to a dubious bridge, from which I leap onto the face, metal-clawed hands and feet stabbing into the snow. At the top of the snowfield I chop a tiny ledge, swap double boots for rock shoes, and move upward on dry rock.

I cover a thousand feet in an hour. It is still night, but day is coming fast. I don’t want to be on this face in the sunshine. A little sun and the snow begins to melt, ice blocks begin to shear off, rocks start falling from the sky. But the sun won’t hit the face until noon, and it’s only 7:30. I remind myself to take my time and enjoy the climb. I stop, sit on my pack, eat a little, and drink a lot. Check out that smooth sunrise turning all the pointy peaks and deadly icefalls a soft, deceiving pink. Little by little, last night’s anxiety is giving way to a reassuring sense of calm.

ALTHOUGH I ENJOY scrabbling my way up almost anything, I came to New Zealand to climb its highest peak, Mount Cook. But after Mount Kitchener, I knew I wasn’t ready. I didn’t know enough yet. So I drove south to Mount Aspiring National Park and hiked up to the French Ridge Hut.

The most poignantly named peak on the planet, Mount Aspiring (9,960 feet) is an extraordinarily aesthetic pyramid of snow and black rock, the one mountain on the tick list of every Southern Hemisphere climber. My objective was the southwest ridge, a classic ice arte. Two other teams in the hut—one American, one Aussie—had the same goal, and I was hoping to tie in with one of them. Unfortunately, they were both gone by one o’clock the next morning. Crunching across the Bonar Glacier around 8 a.m., I met the Americans coming back. They’d turned around due to ferociously high winds.

I carried on to have a look for myself. At the base of the ridge I met up with the Australians; they were packing it in.

” ‘Igh winds and ‘ard ice,” said one of the threesome, who all were from Perth. “Another day, per’aps.”

Craning my head back, I eyed the 3,000-foot ridge. Plumes of spindrift were scouring the top, leaving nothing but a swooping white cleaver of ice. Oddly enough, the scene reminded me of Wyoming in winter. Wyoming and wind are synonymous. After a decade or two, you practically have to be lifted off your feet to even notice. As for hard ice, I’d take that over gripless slush any day. All in all, I figured the route didn’t exceed my conditional comfort level.

Everybody has a CCL. For those born and bred on the coast, rushing seas are de rigueur, and they think nothing of a squall that puts their ketch over to port 45 degrees. (Landlubber to the core, I get queasy in the bathtub.) For those from the desert—Bedouins to Bushmen—100-degree heat is hardly noteworthy. And those from the rainforest find 100 percent humidity no sweat. It’s all what you’re used to.

I summited the southwest ridge of Mount Aspiring in two hours, maneuvering through easy rock bands and connecting ice gullies, staying on solid, slick ice on the leeward side of the arte, exiting through a narrow vertical chute of ice-rimmed stone that reminded me of something I’d climbed on Scotland’s Ben Nevis. The key to determining your CCL is knowing yourself well enough to recognize the risks you can tolerate and those you can’t.

The next morning the weather was so tumultuous, the French Ridge Hut seemed to be cutting through clouds like a ship through swells. There were ten mountaineers aboard, and only one—a square-jawed, 23-year-old Australian sailor named Timmy Gill—wanted to climb. He and I scaled the snowpacked cracks of Mount Avalanche (8,587 feet) in a near whiteout, having a blast together.

“Three hours up, one down,” I wrote afterward on the back of my map. “Rap route indiscernible beneath ice. Left four slings, two nuts. Just off glacier sky cleared like a blessing.”

Times, speeds, conditions, thoughts—I write them down. These postclimb debriefings help me gauge the range of the possible. After a few peaks, I have a baseline of data. I can compare my own ascent rate and assessment of difficulties with whatever a guidebook may say, as well as with the subjective stream of beta from other climbers. In this way I begin to mentally relax and allow the muscle-memory acquired through decades of climbing to carry me.

AFTER MOUNT AVALANCHE, I tried to solo Rob Roy (8,725 feet), a hoary, magnificent mountain also in Mount Aspiring National Park. But I went super- light and got caught out. After 6,000 feet in six hours, I was still 1,500 feet below the summit when another trenchant gale descended. I tried to dig in and bivouac, but without a stove or bag, I started to freeze. To save my bacon, I realized I’d have to turn back and descend through the maelstrom. I lost a glove and my footing several times over 21 hours of continuous climbing.

Two days later I attempted the MacInnes Ridge of Nazomi Peak (9,557 feet) with one of New Zealand’s finest mountaineers, 40-year-old Allan Uren. He’d tracked me down at the Unwin Hut in Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park. It took us two bivies, but we topped out on Nazomi under fine blue skies.

Descending to the Gardiner Hut, we were only a three-hour glacier walk from the Empress Hut and Cook’s Sheila Face, but Allan wasn’t interested.

“I rather feel like a spot of tea,” he said like a true mountaineer.

I had not come to New Zealand to climb alone. I prefer a partner. Climbing with the right partner is safer and more fun, with memories to share years later. But the weather was here now, and I was here now, and the most coveted peak in the Southern Alps was beckoning. I was going up.

Cramponing up the heavily crevassed Hooker Glacier, I jumped each mortal gulf with determination. I stopped several times to glass the Sheila Face with my monocular, trying to commit every outcrop and ice runnel to memory. I’d met two alpinists, Matt and Pete, who had climbed the Sheila Face three weeks earlier. They told me it took them two hours to navigate up the Sheila Glacier and cross the ‘schrund, seven and a half steady and deliberate hours to climb the face, 13 and a half patient hours to descend.

Ogling the face, I poured these numbers into the matrix of what I had learned about myself on the past five mountains in the Southern Alps. With no partner and no protection, on terrain that was not overly technical, I figured I could realistically climb 1,000 feet an hour. The Sheila Face of Mount Cook is 3,000 feet high.

IT FEELS WONDERFUL, powerful, to wield two weapons. I am in my element. Staying left, I climb snow and rock, swiftly locating the lightning bolt I’d spotted thousands of feet below. The ice is thin but grippy, and I am utterly focused. No world exists outside each precise swing of the ax, each sure crampon kick. I am my tools, accurate, unemotional, unapologetic. Where the ice runs out, I stem, my picks hooking cracks, crampons scraping black stone.

I don’t know how fast I’m moving. I don’t know that I’ll climb the Sheila Face in four hours or that in less than ten hours I’ll traverse the entire Mount Cook massif, Empress Hut north to Plateau Hut. At this moment, all I know is movement. I’m not even thinking; I’m just climbing. I shut down the brain and let the body be what it is: an animal.

Unbeknownst even to myself, somewhere high on the Sheila Face, I unlatch the cage. You can’t do this in civil society. It scares people. They think you’re a savage. And they’re right: You are. But the mountain doesn’t mind; that’s what it’s there for. The cage door swings open and out steps the beast. It moves like an agile chimpanzee up glass-sharp jugs of loose rock, then along a rail of stone as stealthily as a catamount, then with ax picks and crampon spikes up the final headwall of ice, quick as a lizard with electric reflexes.

Upward to the knife-edge crest and then, comfortable in its own skin, right to the summit, like a real alpinist.