HEAVEN HAS ALWAYS been hell to get to. I stagger to the top of the pool-table-size summit of the Grand Teton at four o’clock. It’s a glorious afternoon up here, sunny, with just a scrap of wind. , one of our group’s two guides, points north, where on the clearest days you can see ’s hourly ejaculation. Battleship clouds drag their shadows over Jackson Hole and the investment bankers cow-punching on holiday. We’re at 13,770 feet, the literal high point of the Grand Traverse, a classic 13.5-mile hardman’s scamper atop the crown of .��

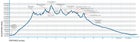

Teton Elevation Profile

The Tetons' Grand Traverse scales ten summits in 13.5 miles, with a total elevation change of more than 20,000 feet. Exum Mountain Guides in Jackson, Wyoming, offers it as a three-day guided trip—for experienced climbers only (from

The Tetons' Grand Traverse scales ten summits in 13.5 miles, with a total elevation change of more than 20,000 feet. Exum Mountain Guides in Jackson, Wyoming, offers it as a three-day guided trip—for experienced climbers only (from

��

,800; exumguides.com).

��

I want badly to appreciate this.

Instead, I’m shattered, so gutted I wave off the views and just lie back and stare into the troposphere, mouth O-ing like a goldfish on the carpet. Halfway through our three-day climb, I’m physically spanked, mentally drooling, sunburnt, dehydrated—and thanks to what the doctors think might be Lyme disease, my veins are coursing with wicked antibiotics that produce sundry and dubious side effects, a fact I’ve kept secret from the guides for fear they’d sideline me.��Today alone we’ve climbed for 10 hours above 12,000 feet. It’s seven more hours before we reach the next camp.

Plus we’re nearly out of food. To shave weight, we’ve cached provisions at the lower saddle, 2,200 feet below. We’re bonking.

On our descent, one of my fellow climbers, Shannon, spies something. He crouches and picks a brown energy globule out of the dirt—a little turd of a thing some previous climber has dropped. Shannon dusts it off and turns it in his hands, considering.

“You think I should eat this?”��

“Uh…”��

“I’m eatin’ it,” he declares, popping the turd into his mouth.

“Ugh!” “Gross!” “Dude!”

I join in the group’s disgust. Secretly, though, I begrudge Shannon his ground booty. Once everyone’s moved on, I search the rocks fruitlessly for more fugitive bits.

THE FACT THAT I’M up here at all is kind of amazing. Earlier this summer, and invited me and a few other journalists to Wyoming with a simple motive: to show how easily visitors to Jackson can��access world-class, soil-your-britches adventure. For proof they dangled the Grand Traverse, a burly tour across the crest of the range in which climbers summit 10 peaks, nine of them higher than 12,000 feet. The guided trip, which is usually open only to those with prior Exum experience, includes miles of scrambling and some moderate rock climbing, up to 5.8 in difficulty—much of it on faces where a sloppily placed foot could make you a headline in tomorrow’s .��

Media trips usually follow a cushier routine: a little zip-lining in the morning, spa treatments in the afternoon, a flinty Sancerre over a four-course dinner. But this was Jackson. And this was Exum, the oldest and most respected guide service in the nation. You have to be invited to apply for a job at Exum (first ascents and exploratory routes on your résumé help), which explains why its staff roster reads like a who’s who of alpinism. But as impressive as the outfit is, even Exum has eyed the Grand Traverse warily. It has only been guiding the route for the past seven years or so; the previous owners thought it posed too many hazards.

“It’s easily the most spectacular alpine climb in the lower 48, and possibly all of North America, that is routinely guided,” senior Exum guide , who has notched about a dozen first ascents around the world, told me as I was preparing for the trip. “Climbers get quick access to��major exposure, long alpine climbs, steep and long faces and couloirs, and virtually endless alpine scrambling.” In terms of punch per acre, the Tetons are some of the most accordioned real estate in North America; the route includes more than 20,000 vertical feet of ups and downs. Local guides simply call it the Traverse.

While the Grand may or may not have been first climbed in 1872 (the date is disputed), nobody thought to try an enchainment until much later. The Traverse was first��completed south to north in 1963. Three years later, climbing pioneers and , a writer and filmmaker who later cofounded the festival, did the Traverse north to south, which purists deem the proper way because you get to do the classic ascent of the north ridge of the Grand. Then, in 1988, famed climbing mutant and Exum guide laced up his running shoes and ran the damn thing in just over eight hours. A dozen years later, another Exum specimen, , completed the Traverse in under seven. “It was that calm that I sought,” Garibotti wrote later, “one that unfortunately vanishes fast, but very rich and textured while it lasts.”

That’s what I was looking for: a little texture.��After college in North Carolina, I moved west precisely to be near big mountains, spending my weekends crawling all over peaks from Colorado’s 14ers to Washington’s Mount Baker. But then I migrated to New York City and grew soft. Now I was back out West—in Seattle—and hungrier than ever for a real adventure.��

IT’S 3:25 A.M. AT THE Lupine Meadows trailhead of Grand Teton National Park. We stand in a circle, Zahan in the center, awash in the rude light of our headlamps.

“We do about half of our total elevation gain in the first push,” he says, referring to the climb from the valley floor to the summit of 12,325-foot Teewinot, 5,500 feet above.��Zahan, or Z, as everyone calls him, is a chatty, bright-toothed 34-year-old who also happens to be Jackson Hole ski resort’s public relations guy.��

Standing with us, saying nothing, with a stoic expression straight out of central casting, is , 42, Z’s fellow guide and an Exum co-owner. Filling out the circle are my trip-mates—Kyle, Shannon, and��Olivia—all of whom hail from high-altitude homes like Santa Fe and Boulder and who look disconcertingly fit, even in the dark. We shoulder tiny packs crammed with freeze-dried food and the latest titanium gear and start upward.

Here I would like to tell you how special it is to move high on a big mountain on a still night, when the world wraps around you as close as a blanket and the air smells of good things—rock and pine and autumn at the edges. I’d like to tell you how, once you find the rhythm of your breath, your mind also finds its rhythm. You can switch off your headlamp and walk by the light of the stars and think that there’s no place you’d rather be.

I’d like to tell you this. But it’s all bullshit. I am in misery. A half-hour up the steep trail, I’m wheezing like an asthmatic pug. Clearly not one bit of the running I did back home in Seattle’s syrupy sea-level air prepared me for working hard at elevation. I choke back my breakfast burrito and keep tromping.

Dawn, when it comes, is a small benediction. When we finally touch Teewinot’s summit, Idaho’s endless potato-field checkerboard materializes from under a dusky halo of��forest fires. I see a lone tour boat dragging its chevron wake across Jenny Lake, carrying some of the park’s four million annual visitors. It’s all so picturesque. And meaningless, for I am obliterated. It’s 8:30 a.m.��

After Teewinot, things get a little hazy. We downclimb. We slip and slide on piles of rocks that have yet to find their angle of repose. We clip in for a 200-foot rappel and head toward 12,928-foot Mount Owen, the Traverse’s��second peak. At Koven Col, we strap on crampons and tightrope-walk across a sketchy snow ridge. Maybe it’s��because I’ve stepped away from climbing for a few years, but the one thing I do��notice with Technicolor vividness is that the possibility of a swift and graphic death is pretty much everywhere up here. If sport climbing at your local crag is like walking across a mossy log, then alpine climbing is like walking across that log while it’s suspended 80 feet over a river gorge—the steps aren’t dissimilar, but the consequences are. That’s why Z and Mike keep us tethered to them—short-roped, it’s called. We’re a litter of wayward puppies leashed to their owners to keep us from falling off the curb, if that curb were 200 feet high and bottomed out in a crevasse.

Worrying about one’s mortality while moving all day at 12,000 feet is wearying enough. Now take away water: we’re each carrying only a quart apiece, in order to go light and move fast. The plan was to refill from pools of snowmelt, but there’s no running water. We go about eight hours before finding a place to drink deeply again. (Stopping to melt snow would take too much precious time.) This doesn’t ruffle the stoic guides, who scarcely sip at their Nalgenes. But I sweat. A lot. And the drugs I’m taking have made me even more sensitive to the sun than normal, which in turn has exacerbated my dehydration. My mouth is Saharan. My legs cramp. The thunderclouds of a headache congeal at the base of my skull and��barrel across my frontal lobe.

“Two down, eight to go!” Mike says��brightly when we finally summit Mount Owen at dinnertime, 15 hours after our day began. Truthfully, I’ve never cared about anything less. I sort of puddle at Mike’s feet. “It’s gotta be tough, or all the riffraff would be up here,” he says by way of encouragement.

He’s right, of course—but all I can focus on is what Mike says next: our camp, a clutch of tent sites clinging by its fingernails to the West Ledges, just below the north face of the Grand, is still an hour and a half away. When he tells me this, I nearly burst into tears.

STRONG COFFEE AND daybreak have a way of dissolving all problems. By the next morning my headache has blown clear. We choke down oatmeal and watch drowsy Idaho��awaken to the west. “Yesterday was the physical crux,” Mike says. “Today is the technical crux.” Overhead, washed in morning’s pilsner light, leans the fabled north ridge of the Grand; in all, we’ll do about 11 pitches of moderate 5.4 to 5.8 climbing to reach the��summit. As if we need another reason to��double-check our harnesses, a rescue helicopter��appears and thwacks around the peak.

The first steps out of camp lead to a catwalk the width of a phone book, above an icy couloir. From there we rappel to a crotch in the rock called the Gunsight, where a cold wind tries to eject us. There’s nowhere to go but up. The rock is already warm in the early sun, a pinkish granite Pollocked with lichen that feels good under hands that have been away from it too long.��

The nostalgic feeling doesn’t last. A few tricky moves later and I’m gasping at 12,000 feet with a pack the size of a toddler on my back, my ass dangling 400 feet over the surly Teton Glacier. Mercifully, holds as big as jug handles soon appear, and I haul myself up to a rare horizontal patch known as the Grandstand, with its stadium views across the valley.��

Before long the entire group is assembled. I gauge the others. Olivia, who has traveled the world covering ski competitions, is a sphinx. If she’s hurting, she gives no sign. Shannon doesn’t show a single crack; a onetime guide on Mount Rainier, he seems expert in the ways of energy conservation. Kyle, an ���ϳԹ��� editor and former professional kayaker who has been filming the entire trip, appears a bit beat up but otherwise buoyant. It’s our guide Mike—Mike is the only one who seems different. It’s as if he’s feeding off the altitude, growing more expansive the higher we go. He’s no longer the stereotypical stoic hardman guide. He goofs around and cracks jokes when he senses one of us is getting a little gripped.��

It’s late morning, but I mention how good a Fat Tire would taste right now. Z cuts me off. “There is one rule about this trip: No one can talk about beer and food until the third morning. Otherwise we’re fucked.” A big smile says he’s joking. Or maybe not. Heads nod; there’s too much jerky, and too many dehydrated meals, standing between us and the Brew We Dare Not Speaketh Of. Besides, it’s time to stop talking and continue climbing, as Z��gently reminds us.��

The two pitches above the Grandstand are blockier and mellower than before, so Mike has Kyle and me “simul-climb,” or move up the rock behind him while he leads. Moving together in high mountains, bantering on a sunny day, we feel a part of something older and more rock-bottom about mountaineering. “It’s like the Matterhorn in 1880-something!” Mike calls down to us. Yesterday, as we trudged upward, each of us was lost in his own cone of suffering. Now on the Grand, linked all day by the intimacy of a few feet of twisted yarn, we urge one another higher, suggest footholds, and bond through our wounds, which are varied and bleeding and growing. That good feeling of hands on rock? It’s gone. “Look at my hands,” Kyle says, holding up his swollen digits. “It looks like I shoved my wedding ring on a hot dog.”

A little higher and the north ridge corrects its posture again, seems to grow even more vertical. The guides decide we’ll take the Italian Cracks, a 5.7 variation that gets lots of sun. “Perfect rock,” Mike says approvingly.

“It looks steep,” I say, a little worried.

“Oh, it’s steep,” the guides say together.

To soften the moment, Mike tells a story about local ranchers’ reactions to pioneering climber when Petzoldt would ask if they’d ever climbed high on the Grand. “The locals would say, ‘I ain’t lost nothin’ up there,’ ” Mike smiles.��

The climbing isn’t so challenging on the Italian Cracks as on those first pitches, but now there’s a thousand feet of air whistling beneath my heels. The elbow room of the Grandstand is a distant memory; at one point, four of us crowd onto a belay ledge the size of a doormat, hugging the rock, as the guides quietly perform the alchemy of carabiners and knots and cordelettes that keeps us from falling into the abyss.

Then we’re moving again. Today will be a twofer: we wrap around the summit block, tag the top of the Grand at 4 p.m., grab our food cache at the lower saddle, and then scramble to the summit of the 12,804-foot Middle Teton, our fourth peak, by headlamp as the last daylight circles the drain. We��finally stagger into a camp below the South Teton at nearly 11 p.m. I’m sleeping even as I roll out my bag.

THE LAST MORNING, Z and Mike take pity and let us sleep in … until nearly dawn. We knuckle the dreams from our eyes and pack quickly. An impossible-seeming six peaks lie between us and the finish line.

This last day turns out to be my favorite. Maybe it’s the promise of a pillowy bed.��Maybe it’s the promise of icy beer. Mostly, though, I love it for what Garibotti��described—how good it feels to move fast in big country. From the top of the 12,514-foot South Teton, the route drops away in a ridgeline spiked with exclamatory towers. Most of the Traverse’s ass-busting and technical climbing is��behind us. For two days, we’ve shuffled clunkily while short-roped to our guides. Now, on this easier terrain, we find our groove. We move fluidly together over the rock. We sling horns without Z telling us to. We set quick belays. We spider up and down faces, touch the top of the 12,400-foot Ice Cream Cone, descend to a notch, and rush toward Gilkey Tower, our seventh summit.

Even a brush with a tombstone-size rockfall on Spalding Peak doesn’t wig me out. The end is within sight, and that makes all the difference. Atop 12,026-foot Cloudveil, we stay just long enough to wonder at new blisters, then rappel to near the base of the final impediment, Nez Perce, an 11,901-foot rubble pile wrapped with balconies of slick grass and surrounded by what Tejada-Flores called “sun-struck, infinite talus.”��

“If we just put our heads down for an hour,” says Mike as we gum our gorp drily in the shade of a boulder, “we’re on the summit.” It’s a grim, panting 60 minutes, but we reach the false summit, scuttle across, and top out. For several minutes everyone just sits in��silence, before a looming thunderstorm��finally��brushes us from the peak.

Later that night, over the best steak I’ve ever eaten, I finally tell the guides the full story about the tick bite, the drugs, the side effects. “I had it a few years back, and the anti-Lyme-disease meds floored me,” says Mike. “I can’t believe you just did the Traverse on ’em.”��

I may never be a hardman. But I’ll settle for impressing one, if just this once.

Back home the Traverse lingers in my mind like a fever dream. Of course, there are physical reminders, too. My ankles swell for days, my nose peels for two weeks. Seven months later, one toenail has yet to grow back. But whenever I survey the damage, I always think the same thing: Damn, I gotta get back in the mountains.