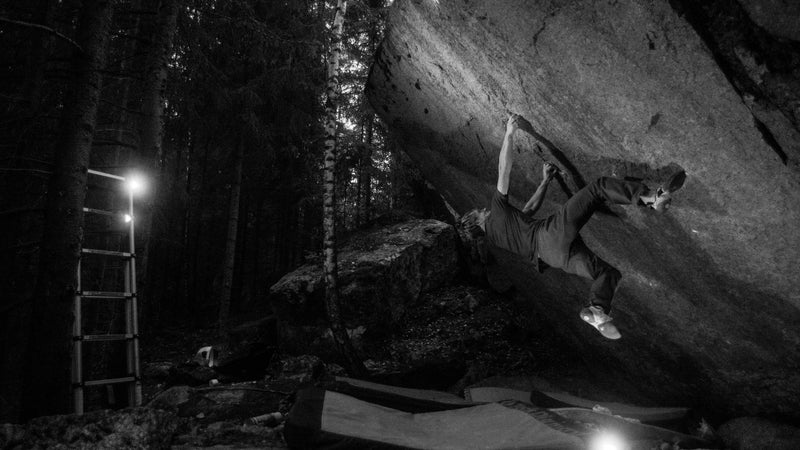

In the fall of 2013, Finnish climber Nalle Hukkataival took a trip out to Lappnor, Finland,��a new bouldering area about an hour east of Helsinki on the country's forested southern coastline. When he arrived, his old friend, Marko Siivinen, pointed out a nameless hunk of rock��the size of a bus that looked like it was about to topple over.

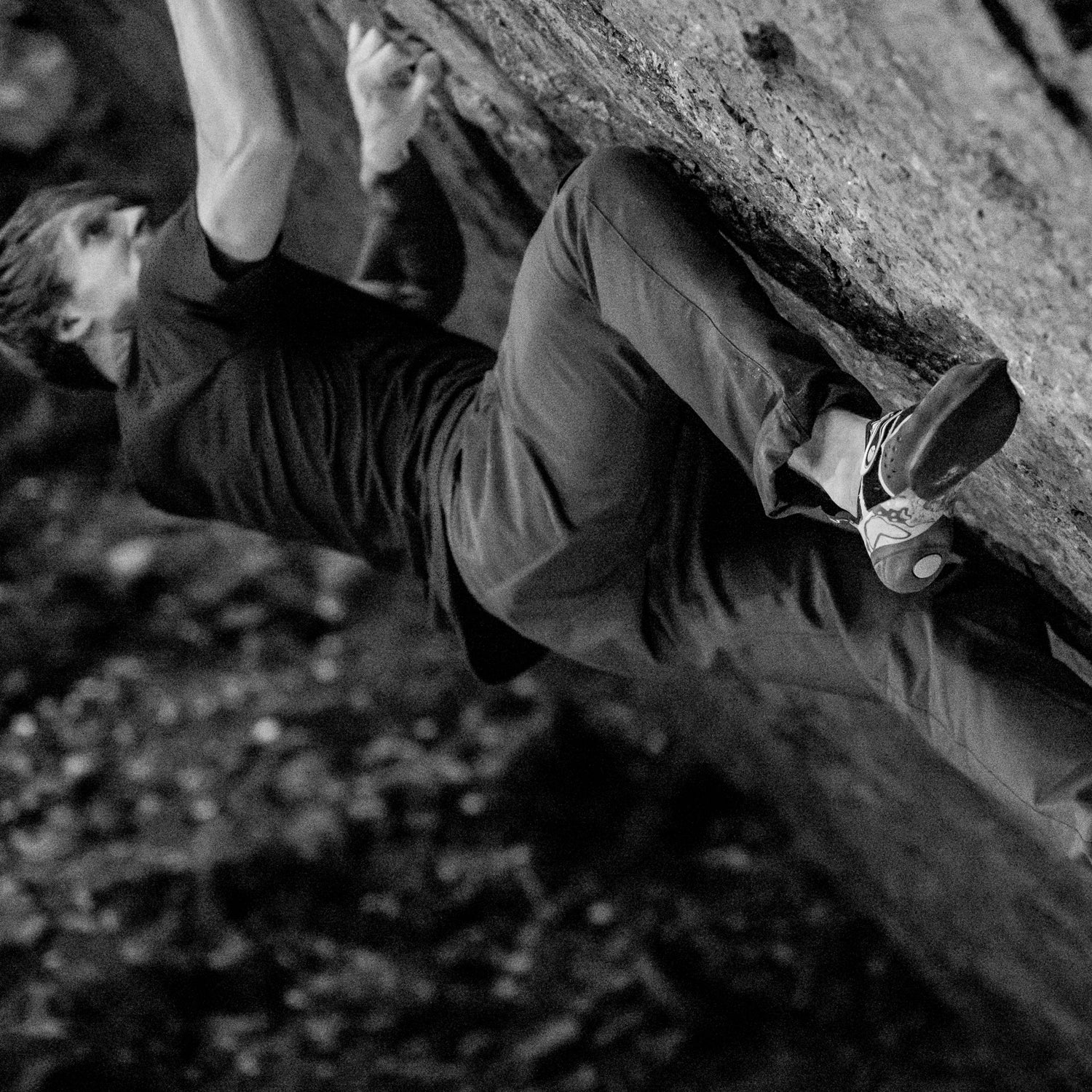

With just a few obvious holds on the flat face, Hukkataival, 30, could see the line to the top immediately. It looked like a V14 problem—expert-level but not impossible. He stepped up to the wall and gripped two vertical ridges, compressing them as though he was closing a sliding door. But the moment he dabbed his right foot onto the wall, he plopped onto the padded mat beneath. It was the first sign that this project wasn’t going to be as easy as he’d thought. “If it looked as hard as it is, I wouldn’t have even tried,” Hukkataival says.

Hukkataival��gives Burden of Dreams a V17 grade. The number of climbers who have scaled a V15 is��fewer than 100. A V16? Just five.

Over the next four years, Hukkataival would make an estimated 4,000 attempts on the��bouldering project before finally conquering it last October. “I thought he was going crazy at some point,” Siivinen, 36,��says. “I was feeling guilty that I showed it to him.”

Hukkataival has given it a V17 grade, which—if given the nod by future climbers—would make it the hardest bouldering problem in the world. As a self-professed guardian of the integrity of the grading system, it’s not a claim he makes lightly, and top climbers who have visited the boulder agree it has potential. “I’ve been traveling for 12 years non-stop,” Hukkataival told ���ϳԹ���. “The whole time I’ve been looking for something with the perfect level of difficulty.” (So far, no other top climber has repeated the ascent, which is the next step in corroborating the V17 rating.)��

To put things in perspective, a V0 bouldering problem is like climbing a ladder. Problems in the V4 to V5 range have skimpier handholds and require the technique and finger strength of a dedicated amateur. V9 and above are pro-level, the kind of problems featured in climbing competitions. Currently, the number of climbers in the world who have scaled a V15 is . A V16? Just five.

This boulder—which Hukkataival christened Burden of Dreams after a 1982 documentary about director Werner Herzog’s monomaniacal quest to move a steamship over a mountain in the Amazon—stands alone. It is like Yosemite’s Dawn Wall writ small, an exercise in frustration that Hukkataival documents in a short film called the , which will be out February 8. The problem consists of just five or six hand movements to the top with funky moves like a piano match, where Hukkataival has to lift his index finger from a crimp to fit his other hand on securely. The footwork may be even more critical. In the beginning, Hukkataival couldn’t even do some of the individual moves, let alone string them together. In total, the climb is a combination of precise, dynamic lunges to sloping holds and powerful body-tensioning static moves.��

Hukkataival is the best climber you’ve never heard of. He’s earned the respect of the sport’s elite, but he’s not a household name like Alex Honnold or Sasha DiGiulian. Part of the reason for his relative anonymity is that he abandoned the competition circuit early and works almost exclusively on smaller canvases: boulders not cliff faces. “It’s the purest form of a pushing yourself where you're not tied down by all this equipment,”��he says.��

He grew up in Helsinki but always loved spending time at his family’s cottage��in the Finnish��Archipelago. At 12, he started climbing in the gym, where the routes quickly grew too easy for him. Skipping holds felt contrived. He gave up climbing for more than a year until a friend took him to an outdoor crag. It was a revelation. “You just go from the bottom of the rock to the top,” he says. “No one tells you what you can do or not.” In 2006, at the age of 20, he was invited to the Arco Rockmaster Competition. He won it and nabbed his first sponsorship from La Sportiva.

But instead of sticking with comps, Hukkataival bought a VW van and spent the next five years in it, exploring crags around Europe, then farther from home. During that time, he conquered some of the world’s most legendary boulders, including Dreamtime in Switzerland, once the gold standard V15, and Livin’ Large, a highball boulder in South Africa, where a 26-foot fall from the top would likely be fatal.

While scoring ascents on some of the world’s hardest routes, Hukkataival developed a deep skepticism of the scoring system. In March 2010, he wrote a ��about the exaggeration—and subsequent demotion—of bouldering grades for new problems. “We can all be throwing out big grades and flashy numbers and get on magazine covers, get better sponsorship and then a few months later watch our problem getting downgraded,” he wrote.��

It seemed like every time someone made a first ascent of a challenging boulder problem, they would claim it deserved a V15 grade, a milestone that was first crossed in 2000 (or 2002, ) and��by 2010��hadn’t been surpassed. But as more people climbed a problem, the grade would slump to a V14. Hukkataival argued for a more conservative, wait-and-see approach to the grading system. “I totally agree that we need to move up on the scale soon, but I'm not sure if the necessary (big) step has been reached yet,” he wrote.

In 2011, when climbers first started throwing out V16 grades, Hukkataival maintained his miserly outlook. After he made the third ascent of Gioia, a possible V16 in Italy, whether it really deserved that grade.��

So how to justify his V17?

Calling it a V16 would have been a cop-out, Hukkataival says, a calculated move to avoid criticism or the sting of the next successful climber downgrading his problem. He wanted to push the grading system forward, and Burden of Dreams felt like the right boulder with which to do that. It’s unquestionably harder than anything he had ever successfully climbed before. He estimates he went to Lappnor more than one��hundred times, filming his attempts sometimes with the help of a cameraman, sometimes on his own.��

By the fall of 2015, Hukkataival felt like he had reached a pinnacle of readiness, and was moments away from sending the problem. Then the snow came. “I stuck around for three weeks looking out the window,” he says. Come spring, he started anew. Fumbling. Struggling. Falling.��

As spring turned to summer, his sweaty fingertips foiled the friction he needed to cling to the wall’s slight bulges. Top climbers, including Daniel Woods and Jimmy Webb, made pilgrimages to Lappnor and agreed that it lay on that thin line that divides the possible from the impossible. “Weeks and months turned into years of uncertainty and self-doubt,” Hukkataival later wrote on Instagram. “Trying to keep that little spark of hope in the back of your mind alive.”

On October 23rd, Hukkataival was out there all alone. He set up his camera and stepped up to the boulder. Everything came together in that one moment. That perfect sequence of moves. Four years flashed before his eyes. He mantled over the lip and couldn’t believe it. When he got down, he texted his friends in Finnish: “Se meni.” It went.��

It was over.��Whether or not the V17 grade sticks,��Hukkataival is already onto his next punishing mega-project. Over the winter, he spent some time in Yosemite with eyes not on the big walls, but on a wet, moss-covered boulder in the valley.