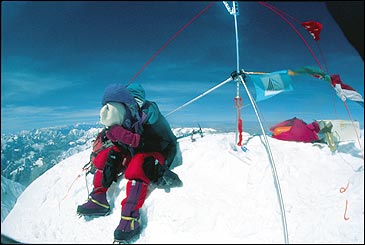

Solid Gold Everest

For a collection of ���ϳԹ���‘s exclusive coverage of Mount Everest through the years,

HOLD ON TO YOUR CRAMPONS. May 29 marks the 50th anniversary of the first successful summit of Mount Everest, by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Record crowds of climbers, trekkers, and gawkers are expected to cram the mountain’s two main base camps—on the south side, at the foot of Nepal’s Khumbu Icefall, and on the north side, along Tibet’s Rongbuk Glacier. The latest predictions put 500 people on the mountain for what is to be an informal celebration, but close to 1,000 may show up, assuming the conflict between the Nepalese government’s forces and Maoist rebels doesn’t escalate in the Khumbu region. The list of folks hoping to summit the Big E in 2003 would’ve made P. T. Barnum proud: 32-year-old Sean Burch, who plans to take Viagra to study its effects as an altitude-sickness preventive (studies indicate that it increases blood flow to the lungs); the Everest Peace Project, whose ten members represent eight world religions; a party of disabled Texans; Gary Johnson, the former governor of New Mexico; polar explorer Børge Ousland; the five winners of Global Extremes, a reality TV show on the Outdoor Life Network; and at least 30 other expeditions from around the globe. At Everest’s primary Base Camp, on the Khumbu Glacier, climbers will enjoy the first Everest cybercafé and the mountain’s first semi-permanent medical clinic. At the Rongbuk base camp, climbers can resupply at tents selling beer, Coke, cigarettes, and anything else they might crave. Even if 2003 represents a spike in the hype, the climbing culture around Everest is bound to continue changing, as it has since the first expedition, in 1921. What does the future hold for the world’s highest mountain—five, ten, or even 25 years down the line? Though it’s unlikely that hovercraft will be ferrying climbers over the Icefall, the crystal ball is both bright and worrisome.

Purists already complain about overcrowding on the mountain, and guides estimate that in future seasons the two base camps could house more than a thousand climbers and trekkers. With the government of Nepal collecting approximately $10,000 per climber on the Southeast Ridge route, and Chinese-controlled Tibet pocketing roughly $5,000 per climber on the North Ridge, neither is likely to put a cap on the number of mountaineers allowed each year. Two schools of thought weigh in whenever the issue of crowds is raised: those who’d like to turn back the clock and allow fewer teams and those who see Everest as an alpine Wild West, where all who dare to try their hand against it should be given the opportunity. “As long as people are prepared and understand the risks,” says 47-year-old filmmaker and mountaineer David Breashears, “I think everybody who wants to should be allowed their shot at glory on Everest.”

Eric Simonson, 48, co-owner of the Ashford, Washington-based International Mountain Guides, isn’t convinced that crowding will necessarily ruin the Big E either. “There are a lot of teams on the mountain these days,” he says, “but I’ve noticed lately that the teams are really cooperating and planning their summit days to not interfere with each other.”

Others don’t have such an optimistic view. Teams typically set different summit days, but poor weather can result in a logjam—as was the case in 1996, when eight people died during a single storm. “Once you start getting 40 or more people on the summit ridge at the same time, you’re going to have a bottleneck, primarily at the Hillary Step, and that can turn deadly,” says 43-year-old American climber and Everest veteran Ed Viesturs. “Now, you’re already starting to see the bottleneck happening on big summit days.” Despite the mounting crowds, almost everyone agrees that guided climbs on the mountain will become even bigger business as more Walter Mittys choose to test their will and VO2 max on the world’s tallest peak.

With crowding comes the issue of development, and efforts to make the mountain more comfortable are getting off the ground. One of the more ambitious projects is a hotel at the Rongbuk base camp. The idea was dreamed up by New Zealand guide Russell Brice, who is building the lodge, complete with bottled oxygen for guests, and is being developed in cooperation with the Chinese government. The hotel, which may begin construction in the next few years, will cater mainly to tourists, who’ll drive 380 miles on a shoddy road—currently being widened and improved—that links Lhasa to the camp. Development at the popular Khumbu Base Camp is less aggressive, but few doubt that a hotel will someday spring up near the foot of the Khumbu Glacier. The primary obstacle to building on the south side is the lack of a road. Currently, a trail that takes two weeks to negotiate on foot separates the camp from the nearest airstrip, at Lukla. And so far, nobody has had the will to cut a road over the treacherous path.

The other major obstacle to building a structure at Base Camp is the fact that it sits on a glacier that moves up to 200 feet per year, which would rip any building apart. Most of the development is happening in the valley below, on the 32-mile trail between Lukla and Gorak Shep, where teahouses, some with as many as 15 rooms, offer dry, warm accommodations and hot meals. As the Khumbu Valley fills with hostels, pitching a tent during the two-week trek to Base Camp becomes less necessary.

On the environmental front, the news is mixed. According to Brent Bishop, 36, who has overseen five environmental cleanup expeditions on the south side—known a decade ago as the world’s highest dump—the mountain is cleaner than it has been in years. Teams are packing out their trash, including oxygen bottles and human waste. Last spring a Japanese team carried down the last empty oxygen tanks from the South Col. An initiative by the Tibetan government, started in 1991, has significantly cleaned up the north side.

Not all the mountain’s problems can be solved with a garbage bag. Since 1953, global warming has changed the face of the peak. Though some argue that the warming trend has made Everest easier to climb because it’s made the Icefall less dangerous, meltwater is creating potential problems for locals. According to several studies in the Journal of Glaciology, the runoff collecting in glacial lakes, some as deep as 400 feet, is putting pressure on moraines that act as natural dams, which threaten to burst and obliterate the villages below.

And what about Everest’s evolving status as the world’s tallest publicity machine? No doubt the record breakers will keep coming. While Nepal has established a minimum age of 16, the mark for the oldest summiter, which was set in 2002 by Tomiyasu Ishikawa, a 65-year-old Japanese climber, will surely be upped. The records for most summits, fastest climb, and most hours on top are all likely to be broken. As Christine Boskoff, owner of Mountain Madness, a Seattle-based guiding company, points out, the sky’s the limit on firsts: “We haven’t seen the first naked climber.”

Even if summiting becomes more common, Everest will remain the ultimate adventure—at least for a few more decades. Breashears describes the mountain’s allure best: “At cocktail parties, the person who solos a new route on an 8,000-meter peak will always play second fiddle to the person who just came back from Everest.”