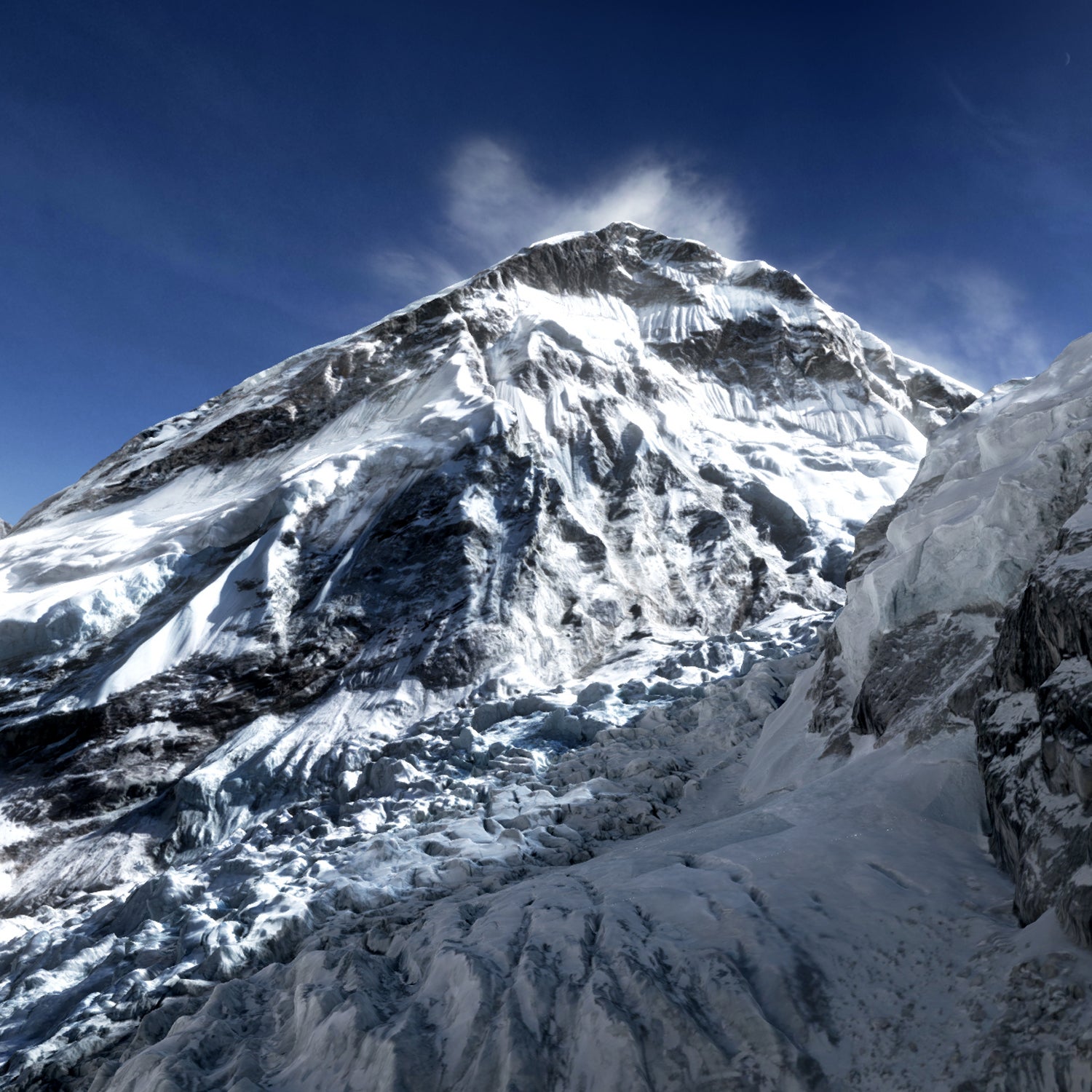

Last month, in a little office above a stale Irish pub in downtown San Francisco, a collection of tech journalists trekked from the Khumbu Icefall, up the Lhotse Face, to the peak of Everest.

The trip was quick—30 minutes—and the guide, Kjartan Pierre Emilsson, had the baby face of a man who’d never battled frostbite in the death zone. But it was exhilarating all the same. Emilsson runs the virtual reality design firm ,�����Ի� Everest VR is the studio’s first big project. The “game,” a faithful (if condensed) recreation of an Everest ascent, will be released this year when , like Oculus Rift and PlayStation VR, hit the market.

To play, users strap on a ski-goggle-like headset, don big headphones, and hold a controller in each hand. The console, in my case the , shot a laser from a base station sensor box into the room to track my physical movements. When Emilsson hit the start button, the outside world faded away.

“This is not a game, like the other stuff being developed” for upcoming virtual reality consoles, Emilsson told me right before we began. “This is more of an emotional experience.”

Everest is the latest byproduct of our enduring fascination with the world’s highest mountain. In fact, the project wouldn’t exist without the last big effort to sell Everest to American consumers—the VR experience uses more than 300,000 photos special that Reykjavik-based effects studio took to create the CGI effects for Hollywood's 2015 film. Emilsson, a stubbly Icelander with a background in traditional video game development, and his studio chose to make the experience partially because of the available footage, partly because of his a preexisting relationship with RVX, and, perhaps most important, because, “Everest attracts a lot of people,” he says. “We hope this product will have a broad range of market.”

Other immersive adventure experiences are cropping up with the advent of 360-degree action-camera setups and drones (like this Nepal experience).�����ܳ� Everest is more than a basic a hiking simulator, Sólfar’s developers say. “I would guess it’s the closest you can possibly get to Everest without being there,” says Reynir Hardarson, the studio’s co-founder and creative director.

“This is not a game, like the other stuff being developed. This is more of an emotional experience.”

Hyperbole has always permeated the “revolutionary” hype surrounding virtual reality. So when I strapped on the headset to try Everest myself, I held my expectations in check. Two minutes into the affair, as I delicately inched across a ladder spanning an ice chasm, I abandoned all pretenses. “Hot shit!” I caught myself saying aloud.* Instinctively, and despite the fact I was standing on worn carpet in the back of a PR office, I was taking care to ensure my feet stepped only on the rungs of the ladder as I navigated the Khumbu Icefall. I made it across the void and took a moment to look around and marvel at the panoramic view of the Himalayas and the peak itself. All of this is to say: VR is no joke.

In the experience, which will probably run only an hour or two and sell for significantly less than the average price of a full-length game, players will start at Base Camp, participate in a , and then make their way up through the four camps and up the Hilary Step to the summit for a panoramic look around.

“In each scene we want to recreate the emotions you’d feel there,” Emilsson says. “Especially in the death zone,” the common term for altitudes above 26,000 feet where the air is so thin that it’s difficult for humans to breath. “If you move too fast in the experience, you start blacking out. We can also force slow down by using heart beat sounds and shallow breathing in the audio track. People tend to empathize with that. It’s like brain hacking.”

Along the trek, the game will present historic tidbits and information about the mountain and the climbers and Sherpa who’ve made it famous. The experience will be a bit sanitized, though: the won’t be included.

“What we’re trying to do here has to be a pretty respectful treatment,” says Solfar’s business developer Thor Gunnarsson says. “What I can promise is there will be no wingsuit jumps off the summit and no skiing down the mountain.”

*Correction: A previous version of this article misquoted the author.