ONE LATE-SUMMER AFTERNOON in the high pastures of Pakistan’s Rupal Valley, Steve House stuck his head out the door of his mess tent and glanced up at the cloud-cloaked mountain that loomed above. Eventually, House knew, the north wind would begin to blow, ushering in the first high-pressure system of the post-monsoon season, and everything would come clear. But it needed to happen fast. Already, ten days had gone by since he and his climbing partner, Vince Anderson, had come down from their final round of acclimatization.

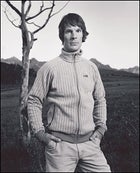

Steve House

House in Ouray, Colorado, July 2006

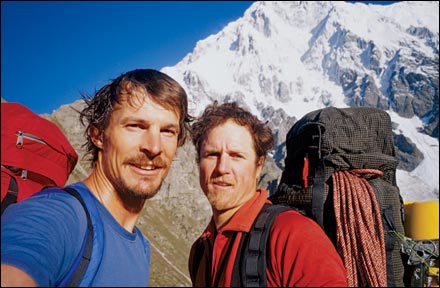

House in Ouray, Colorado, July 2006Steve House and Vince Anderson

House and Anderson at the base of Nanga Parbat.

House and Anderson at the base of Nanga Parbat.What House was looking at, or trying to, was the colossal south face of Nanga Parbat, at 26,660 feet the world’s ninth-highest mountain. Rising nearly 15,000 vertical feet from the valley floor, the Rupal Face, as it’s more commonly known, is an impossible maze of rock towers, hanging snowfields, and ice, sometimes described as the biggest mountain wall in the world. “Imagine this,” Reinhold Messner wrote in his 2002 book The Naked Mountain. “The east face of the Monte Rosa with the Eigerwand above and the Matterhorn perched on top.”

It was Messner, of course, who first scaled the Rupal Face. In 1970, when he was just 25, he and his brother Günther (who would later die on the descent) led the push up a difficult route on its left side as part of a joint German-Austrian expedition. Fourteen years later, a second route, to the right, was established by another Himalayan legend, Polish alpinist Jerry Kukuczka, and three others. For House and Anderson, both 36, an obvious prize remained: the unclimbed Central Pillar, the Rupal Face’s steepest, most direct line and also, undoubtedly, its most difficult. And that wasn’t all. Whereas previous teams had relied on “siege” tactics methodically establishing a series of successively higher camps and using fixed ropes to move back and forth between them the pair were committed to climbing alpine style, in a single bottom-to-top push.

House had attempted the face before. The previous summer, in 2004, he and another partner, Boulder, Colorado based Bruce Miller, 43, had come very close to completing the route. They were five days up the face and less than 2,000 vertical feet below the summit when House, who had led most of the tough pitches on the way up, began to feel the effects of altitude sickness and slowed dramatically. After an agonizing hourlong discussion, Miller became convinced that House’s life was in peril, so he persuaded his partner to turn around a decision that House would later, and quite controversially, suggest was more a reflection of Miller’s fear than of his own incapacity.

Meanwhile, others had set their sights on the Central Pillar. When House, Anderson, and two other American climbers, Scott Johnston and Colin Haley (who were there to attempt a previously climbed route on Nanga Parbat), had trekked into the Rupal Valley three weeks earlier, they’d found Tomaz Humar, the celebrated Slovenian alpinist, already ensconced at the prime base-camp location in Baseen Meadows, along with a small army of followers a film team, a Web-site technician, even, according to House, an “aura reader.” The Americans exchanged pleasantries with Humar and kept walking, eventually establishing a camp of their own in Latoba Meadows, a two-hour walk upvalley. “I wanted to be as far away from that circus as possible,” House told me when I hiked in a few weeks later.

By then, the details of Humar’s botched summit attempt had become the talk of the mountaineering world. The day after House and Anderson’s arrival, the Slovenian had launched a solo bid up the middle of the face. He wound up stuck on rotten ice at 19,350 feet, pinned down by the weather and out of food and water. Nine days later, after a series of dramatic radio transmissions, Humar was snatched from the precipice by a daring Pakistani army helicopter pilot. The general consensus: The Slovenian had pulled a stupid stunt, endangered others’ lives, and was lucky to have survived.

On my first night in base camp, as we dined on chapatis and a freshly killed chicken prepared by expedition cook Fida Hussein, House offered his own piquant analysis of his rival’s misadventure. The way he saw it, Humar had been defeated not just by hubris and bad planning he wasn’t fully acclimatized and had set off despite a sketchy weather forecast but by the overwhelmingly commercial nature of his expedition. It was “interesting,” House said caustically, that Humar claimed to have run out of food and fuel but still had plenty of batteries to power his radio, “so he could do daily dispatches for the Slovenian national radio network, which just happened to be one of his major sponsors.”

To House, a dedicated minimalist who argues that any extra weight even that of, say, a video camera could mean “the difference between life and death” on a long, tough route, the implication was clear: Humar was less a cutting-edge alpinist than a careerist profiteer.

House tipped his chair back and shook his head dismissively. “It’s not like you need a lot of money to climb these peaks,” he said, offering as evidence his own budget for six weeks in Pakistan: just $10,800, split evenly among him, Anderson, Johnson, and Haley. “I’ve never understood the whole argument for sponsored expeditions,” he concluded. “To me, the money just gets in the way.”

AT FIRST GLANCE, Steve House doesn’t fit the image of a super-alpinist. At five foot ten and 165 pounds, with rounded, sloping shoulders, he’s not particularly imposing. His dark, darting eyes can sometimes give him a look of feral intensity, but his manner is friendly and down-home, sometimes even shy. One of his early mentors and climbing partners, Canadian alpinist Barry Blanchard, calls House “Farm Boy,” because, as Blanchard once wrote, he “looks like he should be chewing on a stalk of straw and slicing into his mom’s fresh apple pie.”

Yet over the past decade, while much of the public’s attention has been focused on the cattle route up Everest, House has pursued a completely different kind of climbing, stringing together steep mixed pitches of rock, ice, and snow in head-spinningly fast times, even at very high altitude. In 2001, for example, climbing in the Alaska Range with Boulder, Colorado’s Rolando Garibotti, he summited one of North America’s hardest routes the 9,000-foot line on Mount Foraker’s Infinite Spur in just 25 hours, more than six days faster than the previous time. That same year, as an “experiment,” he raced up and down an 8,000-meter peak, Tibet’s Cho Oyu, in less than a day.

There’s one other thing that sets House apart: his tongue. In recent years he’s made a name for himself as America’s leading advocate for alpine-style climbing and as a relentless critic of anyone who doesn’t climb that way. House doesn’t just practice alpinism; he preaches it on both environmental and personal grounds.

“There is and should be repulsion at the idea that people leave camps and ropes and trash in the wilderness and permanently deface the rock by bolting it,” he says. “It trashes the resource and changes the experience of everyone who comes after.”

Another of House’s arguments is harder to articulate, but it’s just as strongly felt. “I need another word, but there’s a moral or ethical element here,” he told me in Pakistan. “Climbing is a form of expression that has no practical purpose it’s for one’s own personal satisfaction. So to climb in a manner that is not what I call moral is to diminish your own experience. We already know we can climb any route with enough technology. So what’s the point? That’s not interesting. Uncertainty is the most important aspect.”

One of House’s first public salvos about all this came in 2000, when The American Alpine Journal an annual compendium of “the world’s most significant climbs” put out by the American Alpine Club published an essay in which he decried “business climbing.” He singled out a commercially sponsored expedition to Pakistan’s Great Trango Tower, made the year before by Mark Synnott, Jared Ogden, and the late Alex Lowe, in which the three, accompanied by a camera team, sent out regular Web broadcasts from their portaledge. Besides “degrading” the caliber of the climbing, he railed, any climbs that rely on bolts and fixed lines, as this one did, “do not stretch our collective experience any more.”

House has kept up the debate ever since. More recently he’s aimed his cannon at the Russian Big Wall Project, a ten-year initiative led by St. Petersburg based Alexander Odintsov to conquer the world’s biggest unclimbed walls in classic siege style. “They’ve got some incredible things on their list the west face of Makalu, the west face of K2 and they’re going to wreck them for the rest of us,” House says. “It makes me sick to think about it.”

House’s biggest outburst to date occurred at the 2005 Piolet d’Or, or “Golden Ice Ax,” an annual Oscar-style awards show in Grenoble, France, put on by the French magazine Montagnes to recognize the greatest alpine-climbing feat of the preceding year. Not surprisingly, House had been nominated for his 2004 solo effort on K7, a 22,776-foot peak in northern Pakistan, until then climbed just once. House had ascended it, via a new route, in one sleepless 41-hour push. To his consternation, however, among the other five nominees was a 12-member Russian expedition that had scaled the north face of 25,295-foot Jannu, a sheer wall in Nepal considered one of the climbing world’s “last great problems.” House objected to the way the Russians had sieged their route, the dozens of bolts they’d drilled, and the fact that they’d left most of their gear (including 77 ropes) hanging on the mountain. When they won the award, he stormed off the stage.

That performance drew its own catcalls. “I really think people like Steve miss the boat of public appeal and interest with the dogmatic approach,” says Kelly Cordes, 38, a Colorado climber and a senior editor at The American Alpine Journal. “His climbing speaks so loudly that, it could be argued, his bantering actually weakens his cause. Many people view it as a pissing match, and they’ve got a point.”

In a 2005 article in Climbing, Synnott defended the Russian approach as a bold effort by determined climbers who were coming out of a different, communitarian tradition. “There exists a category of people with a firm knowledge of how one is supposed to live,” Odintsov, the Jannu expedition’s leader, told Synnott, in an obvious reference to House. “To them, it’s absolutely necessary that everyone around them live life by their patterns.”

“In alpinism, if you take ethics away, there’s nothing on the other side only helicopters,” counters Marko Prezelj, a Slovenian climber and frequent expedition partner of House’s. “If you’re not harsh, nobody listens.”

Even those who share House’s views have been taken aback by his apparent willingness to sacrifice everything, even friendship, to make a point as he did last year when he seemed to attack Bruce Miller, his partner on the 2004 Rupal Face climb. In an account he wrote in the spring 2005 issue of Alpinist, the bible of the hardcore mountaineering crowd, House said it’s impossible to know what might have happened if the two had kept going. “It would have been the greatest accomplishment of my life. But I had to go down with Bruce because his no was necessarily stronger than my yes,” he wrote. “Bruce had acted on fear… At 7,650 meters, Bruce’s overriding fear had become me, become my death.”

House still thinks the climb could have succeeded. “I believe [Miller] believes that we needed to go down,” he told me in Pakistan. “I think it’s a possibility. But, really, I don’t believe it. We’d done 300 meters in three hours, and we were 600 meters from the top that’s my answer.”

Not everyone agrees, including a friend of both climbers who asked not to be named but clearly thinks Miller did the right thing. “Look at the pictures from that trip,” this person wrote in an e-mail. “Steve’s head is swollen like a watermelon… When Steve dissed Bruce in that article, it REALLY put off a lot of people. Frankly, Bruce saved Steve’s life I remember Bruce telling me that Steve admitted that he was willing to die for the route. (Bruce, so low-key, told me, ‘Well, I thought to myself, Ya know, that might be OK for you, but it’s really not alright by me.’)”

Miller was more circumspect when I reached him by phone. “On day four, this lung crud started to catch up with him,” he said. “By the last day it was pretty clear to me, and I felt like I had to make a call. I thought my partner was dying.” He paused. “I thought it was weird, that account he wrote. Let me put it this way: I need all my fingers and probably a couple of toes to count my friends who I don’t have anymore, who I wish were alive to give me shit.”

AS AUGUST ROLLED on at the base of Nanga Parbat, the days grew shorter and the nights chillier. In the meadows, the sheep and goats bent to the grass, packing on the fat, and in the mess tent it was pretty much the same: nonstop chomping. If the tension was mounting, it was hard to see. What was apparent, though, was that Anderson, with his pierced ears and nipples, and the straitlaced House were getting along like old friends.

But they weren’t old friends, really, even though they’d first met in Alaska in the late nineties and had done some work together as American Mountain Guide Association instructors. (While Anderson still works full-time as a guide, House’s main employment these days is as an “ambassador” and product tester for Patagonia.) Over the winter, House had, in Anderson’s phrase, “cold-called” him about the Rupal climb. Amazingly, until their rounds of acclimatization on Nanga Parbat, the two had never done any serious climbing together.

“I think some of our strengths are complementary,” Anderson told me. “I can keep it rolling pretty much forever, albeit slowly. On the other side, Steve has a lot of fortitude, and he’s smart at figuring things out. I don’t know I might balance out some of his eagerness.”

House, too, seemed cautiously optimistic. “An alpine partnership is probably one of the most challenging things in the world,” he said. “It’s not easy to trust like that. Messner and Habeler, Boardman and Tasker there haven’t been a lot. It’s rare.”

Then again, the two have a lot in common. Both grew up in the West House in eastern Oregon, Anderson in central Colorado. Both are smart and thoughtful, House with a degree in environmental science from Olympia, Washington’s Evergreen State College and Anderson a University of Colorado graduate in architectural engineering. And both possess an innate sense of style that extends to more than just climbing. “I’m just a dirtbag,” Anderson says, “but, still, I hate surrounding myself with cheap plastic stuff.”

Anderson got into mountaineering via a teenage interest in steep backcountry skiing. For House, the path had a lot to do with his decision to spend a year studying abroad after graduating from high school in 1988. His father, Don, a former accountant who still lives in LeGrande, Oregon, with House’s mother, Marti, a retired teacher, had to pull out an atlas to find the country to which his son was assigned: Slovenia, a tiny, mountainous enclave at the eastern end of the Alps. House’s outlet there was climbing practically the national sport. He joined a local outing club and spent every weekend in the mountains.

“I think he learned from the Slovenian climbers, who are accustomed to much harder living than we soft Americans are, what was ‘normal’ in the mountains,” says Mark Twight, a climber, writer, and alpine-style hardliner who’s known House since 1998.

In 1990, after his freshman year in college, House joined some of his Slovenian clubmates on an expedition to Nanga Parbat’s Schell Route, just a few miles west of the Rupal Face. The bid was successful, placing two climbers on the summit, but for the 20-year-old House, it ended with him vomiting in the snow at Camp II. “I left very humbled,” he recalls. “I was so undergunned I had no business being here.” At the same time, he adds, “it’s not surprising I conjured it as a dream.”

After graduating, House moved to Mazama, Washington, and started work as a climbing and backcountry-skiing guide in the North Cascades, often in tandem with his college sweetheart, Anne Keller, whom he married in 1995. (The two divorced in 2004.) Over the next ten years, he completed nearly 30 expeditions in Alaska. His first big route, in 1995, was a fast and light assault on Mount McKinley’s 4,400-vertical-foot Father and Son’s Wall, which he climbed with another guide, Eli Helmuth, in 33 hours.

It was in Alaska, a year later, that House met Alex Lowe, who invited him to a frozen-waterfall-climbing “gathering” in Cody, Wyoming an experience that House says was “pretty much like Larry Bird asking me to shoot a few hoops.” In Cody, mixing with a dozen of Lowe’s friends, the elite of the alpine world, House made a strong first impression.

“There were new routes to climb all over the place, and Steve and I put up a couple one day,” recalls Bill Belcourt, a manager at Black Diamond Equipment. “Steve had an easy grace that was beyond his years. He showed a lot of patience and control, and there was nothing flashy about his climbing style, something that showed a profound level of maturity. I liked to say, ‘Steve climbed like an old guy.’ “

Soon, House found himself climbing big routes with alpinists whose pictures he had once cut out of magazines: Barry Blanchard, Scott Backes, and Mark Twight a close-knit group of alpine-style purists. In 1999, he led the charge on a new route called M-16, on Howse Peak, in the Canadian Rockies. The crux was an insanely fragile 200-foot tongue of vertical ice that was one to two feet wide and in places about half an inch thick. House took three and a half hours to negotiate the pitch, then fixed an anchor with eight ice screws to belay his partners. “It was as hard as anything I’ve ever done,” he says.

Twight, whose angry climbing screed “The Rise and Fall of the American Alpinist” had turned House on when he read it in high school, became a mentor. After he, Backes, and House completed the most notorious climb of the 2000 season, a 60-hour, 9,000-vertical-foot route on McKinley called Czech Direct, he told House that his own career was winding down, adding, “You must know deep inside that this responsibility will pass to your shoulders sometime.”

House hated the pressure that came with such pronouncements. At the Ouray Ice Festival a few years ago, he stood up to give a slide show about the “progression” he saw in his own climbing career. As he was trying to explain why he’d recently shifted his focus to the Himalayas “Basically, there was no terrain left in Alaska that was big enough” a British rock climber who’d had a few beers loudly called House an “arrogant cunt.” House was stunned but gathered himself and went on.

“I was unprepared for the burden of proof being directed at me,” House says of his rise to prominence. “I’ve thought about just not responding, but I feel like if I don’t, I don’t know who will.”

ONE AFTERNOON, when House and Anderson were out bouldering, Aslam Rana, House’s liaison officer a government representative that every expedition in Pakistan is assigned excitedly returned from a visit downvalley to report that a large party headed by Reinhold Messner was setting up its tents at Tap Meadows, the same place the German-Austrian expedition had been based 35 years earlier. ” ‘Vee camp here!’ ” a giggling Rana said, mimicking Messner’s imperious proclamation.

I walked over at teatime and found Messner at the head of a long table in his mess tent with 15 German trekkers he was leading on a two-week trip around the mountain. At 60, Messner still looked fit, with a bushy beard and that famously thick head of hair. He didn’t seem particularly impressed by the details of House’s project.

“Yes, the only possibility is the Central Pillar,” he said, as if he’d scoped it himself long ago which he probably had. He did ask one question: Would House be carrying a radio? “I call it my ABC,” Messner said. “No Artificial oxygen, no Bolts, no Communication.” No radio for House, I told him, though he was planning to use a sat phone from base camp to consult with a weather forecaster. “Ah,” said Messner, visibly pleased at this sign of weakness. “But isn’t that judgment part of alpinism, too?”

Nevertheless, the next morning Messner, wearing a jaunty Tyrolean hat, strode into our camp. Hussein and Rana pulled out some chairs, and Messner, House, and Anderson sat down for a cup of coffee while a photographer with the German group scuttled around. House was excited; he’d told us the night before that he still has a copy of the Tyrolean’s famous alpine-style manifesto, “The Murder of the Impossible,” taped to his office wall.

Messner’s style at this meeting was more press conference than conversation, though. The only time he seemed truly curious was when House told him he’d climbed with Twight, an author Messner admires because “he has rediscovered the spirit of the 19th-century writing about the mountains.” Otherwise, Messner was mostly dismissive. When Ed Viesturs’s name came up, for instance the American had just completed climbing all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen, the famous feat Messner had pioneered the Tyrolean rolled his eyes.

“Now I hear a woman is trying to do it,” he said disdainfully. “It’s silly the most boring kind of climbing.”

House grinned impishly. “Yeah,” he said. “I wonder who invented that, anyway?” Messner didn’t crack a smile.

I’d like to be able to report that, as he left, the world’s most famous alpinist cast an envious eye on the younger men or clapped them on the back. But no torches were passed, ceremonial or otherwise. Messner stood and posed for a few last pictures with House, nodded a curt farewell, and strode off at a fast clip, his retinue in tow.

House seemed more amused than disappointed. “He projects this idea that alpinism is over: He did all this stuff; now it’s finished,” House said. “But, hey, he’s still the man.”

THAT SAME DAY, House and Anderson began packing for their climb. They did the food first: piles of Stove Top stuffing with packets of Gu and baggies of a powdered drink mix called Spiz, enough for 12 days. “In Alaska, you’d take [enough for] 24,” Anderson said, and House nodded, tossing in some chunks of halvah and a few tins of kippered herring, which he called “my own special burden.”

A day later they started winnowing their gear, an exercise in minimalism that was spectacular to behold. Their single-wall tent weighed two pounds. Their sleeping bag why take two? was a featherlight quilt of Polarguard that House had stitched together himself and that compressed to fit inside a helmet. Their “rack” was, by rock-climbing standards, tiny: five ice screws, nine stoppers, or nuts, nine titanium pitons, three spring-loaded camming devices, 20 wire-gated carabiners, two locking carabiners, and two rappel devices. The only redundancy was an extra camera. “In the modern world of climbing,” House noted, “if you come back without pictures, no one will believe you.” In all, it came to 64 pounds; by splitting the load, they’d be able to do most of the climbing with their packs on.

On the evening of August 27, my last night in camp, House placed a sat-phone call to a meteorologist in Jackson, Wyoming, and got a provisional go-ahead. The next morning, at 4 a.m., I joined the two for a hike to the glacier where the route begins. But at dawn, the cloud deck was still hovering menacingly a few thousand feet above the valley floor, and when I left them an hour later they were pondering whether to launch or not.

In the end, they started four days later, on September 1. Day two was technically the hardest, with several ice pitches up to 90 degrees, while day three was the longest, an 18-hour marathon with more than 30 pitches that ended only when they found a bergschrund on which to camp. The psychological crux came on the fourth day, when they had to find a way through a seemingly impassable rock band and did after a desperate hour of searching.

“If we hadn’t,” House told me later, “we’d have been looking at 60 to 80 rappels to get down, and with the gear we had we couldn’t have done it.”

Summit day, day six, was interminable. They’d camped at 24,278 feet, but soft snow in the morning bogged them down, and it took an hour to make the first 200 feet. When House looked over at Anderson and asked him how he felt, Anderson put a finger to his temple and pulled an imaginary trigger a positive sign, House concluded, because it meant Anderson was “still able to make a joke.”

They reached the summit just before sunset, stayed an exultant 15 minutes, returned to their high camp, and, after a few hours of sleep, descended via the Messner Route, the same way House and Miller had bailed the year before. A day later, as they stumbled down the moraine in a state of complete exhaustion, four strange men came running out of the junipers and embraced them in terrifying bear hugs. It took House a few minutes to realize that among them were Rana and Ghulam, the assistant cook. In base camp, House hugged a tearful Hussein.

“Success, Fida, success!” he said, before the emotion became too much and he stole off to his tent.

IN JANUARY, at the Ouray Ice Festival, House gave a slide show about the climb to a packed crowd, admitting that he’d been fairly depressed after the ascent. The last word of the night came from a man with a cane standing at the back of the room: Jeff Lowe, a Utah climber who was once one of America’s top alpinists and is now stricken with multiple sclerosis.

“Rather than a question like everyone else had, he just had a comment that brought huge applause,” says American Alpine Journal‘s Kelly Cordes, who was there. “Something like ‘Steve, you shouldn’t be depressed. You’ve done something great and you’ve brought it all back to everyone here. Congratulations on a truly great ascent!’ “

“Jeff could certainly relate to Steve’s ambition and life-driving passion for climbing as much as anyone ever could,” Cordes continues, “and here he is, one of the all-time greats, now dealing with something much bigger than climbing, offering those pure and positive words of encouragement. It put a lump in my throat.”

The next month, House and Anderson flew to France for the Piolet d’Or awards and won hands down. After House threatened to bolt the “yellow ax” to the bumper of his van, Anderson took it home “for safekeeping.” The two stayed close, and even though Anderson’s wife gave birth to a baby boy in June, he headed back to Pakistan with House late in the summer to attempt the “gnarly” south face of the unclimbed east summit of Kunyang Chhish, a 25,590-foot peak north of Gilgit. “We had one great climb together,” Anderson told me a few days before they left. “This one may not have the same magic as the Rupal, but I hope it does.”

For the moment, at least, the partnership was intact. And in the end, perhaps that was the thing House had been seeking all along maybe even more than the Rupal Face itself.