Life and Death on El Capitan

Tim Klein and Jason Wells were weekend warriors. They were also two of the best climbers to ever ply their trade on Yosemite's most iconic wall. So the climbing world was stunned when they died on some of its easiest terrain.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Jason Wellsâs phone buzzed as photos of crumpled climbing garb popped onto his screen.

âKnickers, pants, and 2 of socks, underware [sic], shirt, fleece. Also puffy and new with tagsâŠrain jacket,â wrote Tim Klein in an accompanying text message. It was Thursday May 31, 2018. Early the next morning Jason would fly to California and the pair would head to Yosemite to climb El Capitan, as they had dozens of times before.

Tim, a 42-year-old teacher at a low-income public high school, lived with his wife, JJ, and two young sons in Leona Valley, a quaint ranching hamlet an hour outside Los Angeles. After climbing together in Yosemite, Jason would often stash clothes and gear at Timâs home, a cheery one-story cottage decorated withÌęframedÌęAnsel Adams prints and bible passages taped to the wall. That way he didnât have to shuttle so much back and forth from Boulder, Colorado, where the 45-year-old lived with his wife, Becky, and ran an asset-management firm. Tim and Jason climbed together in Yosemite so frequentlyâaround eight weekends a yearâthat the arrangement made sense.

On this trip, they planned to tackle two El Capitan routes in two days: the SalathĂ© on Saturday, June 2, and the Nose on Sunday, June 3. To most climbers, this mission would sound quixotic, but for Tim and Jason it was routine. While teams often take between three and five days to scale El Capitanâs 3,000 vertical feet of smooth granite, Tim and Jason usually summited in seven or eight hours. Occasionally they turned around and scampered up El Cap a second time in the same dayâa stunning achievement for two recreational climbers in their forties with families and intense careers.

âRental car is booked for less than a rental bike at the beach,â Jason messaged Tim as he packed for California. âFlight arrives at 10 but will hit [Trader Joeâs] and can work at Starbucks till whenever unless you want me to remove another stump. Psyched up!â

Jason was referring to the time he had landscaped the Kleinsâ entire front yard while waiting for Tim to finish work so they could leave for Yosemite. Driven by deep religious faith, Tim dedicated himself to serving others, both as an educator and outside of school, where he coached a soccer team comprised of players with special needs. Jason, who had a knack for handiwork, was always eager to help him and JJ when he could.

This trip, the honey-do list that JJ had prepared for Jason was minimal: just a few dead light bulbs to change. In return, JJ handed him his climbing clothes, which she had washed and folded, as always.

School had just let out for the summer, and Tim made it home around 2 P.M. As he and Jason tossed their gear in the trunk and sped off toward Yosemite, JJ recalls that the men were even giddier than usual.

The week before, Tim had been named Antelope Valley Union High School Districtâs Teacher of the Year for his leadership of Palmdale High Schoolâs Health Careers Academy, which prepares students to enter medical professions. His students adored his EMT classes, which he livened up with anecdotes of climbing adventures, and praised him for his generosity. When he received a $4,000 teaching bonus, he distributed it back to students in the form of $100 grants with a catch: the money had to be used to help someone else. To inspire a student to return to school after she was shot in a drive-by incident, he smashed the Guinness World Record for climbing the height of Everest on an indoor climbing wall. Once he quietly bailed a studentâs mother out of jail.

As they zipped past the flat fields of Californiaâs Central Valley, Jason was similarly jubilantâhe had recently learned that Becky, at 41, was pregnant with their first child. Shortly before he left for California, he and Becky went to the top of the first Flatiron, a peak outside Boulder, and opened an envelope from their doctor with the message âItâs a girl!â Jason had a teenage daughter from a previous marriage, and he was excited for her to have a sister.

After a few hours of driving, Tim and Jason neared Raleyâs supermarket in Oakhurst, 30 minutes from Yosemite, where they usually picked up sandwiches for dinner. They often competed to see who could get a bigger discount. âSince we present the deli staff with a gleaming pre-[El Capitan] ascent smile that is hard to miss, the price is negotiable,â Jason once wrote in a trip report on SuperTopo, an online climbing forum. He called it their â.â

From there they continued to their sacred Yosemite sleeping spotâan undisclosed, not-quite-sanctioned camping areaâand went to bed.

Jason and Tim met by chance around Christmas in 2004.

Tim and JJ were visiting Timâs parents in Orange County for the holidays when his back began to throb. As a teenager, Tim had ridden on a team with Floyd Landis, the Tour de France competitor, until he ruptured three discs in his back and began having seizures. After that, he could no longer board planes or sit for long periods, let alone mount a racing bike. One of the only activities that soothed his pain, curiously, was climbingâa hobby heâd picked up with his brother as a kid.

The couple thought about where they could go and settled on Mount Woodson, a granite climbing area north of San Diego. JJ felt torn. While she wanted to help her husband, she was less keen to wear a harness all day. She was five months pregnant with their first child, and even seatbelts felt constricting against her bulging belly. âI prayed to God to send me someone who could belay Tim so that I wouldnât have to,â she remembers, chuckling.

A few minutes later, a pickup truck chugged into the Mount Woodson parking lot. As the driver hopped out and began pulling together his ropes and gear, JJ sized him up: he was tall, slim, and sandy-haired, with a gentle face and bright blue eyes. More importantly for her purposes, he was alone and looked fit. âYouâre my guy,â she recalls thinking. JJ, a petite brunette with a sunny demeanor, asked the man where he planned to climb that day. When he said he was headed to the same route Tim wanted to try, JJ silently rejoiced.

The men decided they would take turns doing laps on the same pitch. While Tim zipped up and down, his back relaxing with each ascent, JJ asked the other climber about himself. His name was Jason Wells and he was in the San Diego area visiting his parents with his wife and young daughter, Amelia. His uncle had introduced him to climbing as a teenager, and heâd been hooked ever since, climbing at the gym on nights he could escape his job in finance and scaling big walls in Yosemite when he could take weekends away from his family.

Had he ever climbed El Capitan? JJ asked.

Summiting the iconic granite monolith had long been a dream of Timâs, but one that seemed farfetched. Most ascents of El Capitan take several days. Because of his back condition, Tim couldnât climb with a haul bag; any climbing partner would need to carry his food, water, and portaledge, in addition to their own. He had attempted El Cap twice, but in one case his partners couldnât even lift the massive bag off the ground.

Jason said that he had climbed El Cap several times but found hauling gearâwhich he did only onceâmiserable. He wasnât interested in any more multiday ascents.

When Tim descended to belay Jason, JJ grabbed him excitedly by the arm.

âThis guyâs your ticket up El Cap.â

Tim grinned as he wiped the sweat off his pale forehead and into his blondÌęhair. He was lean but solidly built, with wide features, dense muscles, and blue eyes that squinted in the sun. âThatâs not really how it works, love,â he said teasingly. âYou donât just meet someone and do one pitch with him over and over again and say, âHey, letâs go do El Cap.ââ

JJ insisted that Tim at least ask for Jasonâs contact info, which he sheepishly did before they got in their cars and drove back to their respective lives.

When Tim still hadnât connected with Jason after a few months, JJ stepped in again. âDonât let this guy get away.â

Tim reached out, and the men made plans to meet in Yosemite.

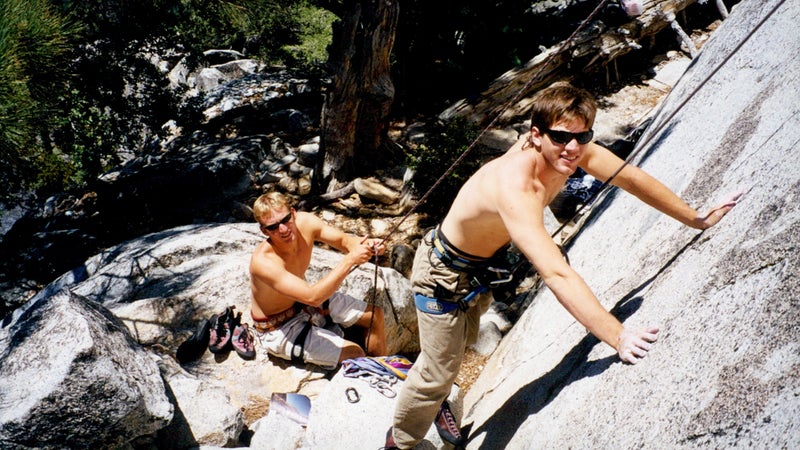

After their first Yosemite trip, Jason and Tim began climbing together regularly, tackling classicÌęshorter Valley routes like the Steck-SalathĂ©, Washington Column, the Rostrum, and Astroman. They quickly realized their priorities and climbing strengths aligned to make them a formidable team.

Tim loved aid climbing, using tools like ladders and ascenders to move up the rope on particularly steep or overhanging sections of rock. By contrast, he compared JasonâsÌęaid climbing to â.âÌęJason was much happier with his hands and feet touching stone. Both men were naturally fast and had a similar tolerance forÌęrisk. Each had extraordinary endurance. When they took a weekend to climb, they wanted to maximize their time on the rock before rushing home to their families.

They alsoÌęhad a blast together. Listening to Tim and JasonÌęclimb up a wall made it hard to believe both men were sometimes described as shy. âTim on the headwall, aw yeaaaah,â Jason once narrated as he shot a video of Tim leading a pitch. âWoooo!â Tim shouted from up above.ÌęâAnd then,â Jason said as he panned the camera down towards the treetops of Yosemite Valleyâs ponderosas. âWoo-hoo, yeee-ah!â

The rock seemed to melt their inhibitions. They had pre-dawn dance parties with other climbing teams before beginning their ascentsÌęand cheerfully chatted with every party they passed, whichâgiven their speedâwas many. One climber who encountered Tim and Jason in Yosemite compared being overtaken by Jason to being passed by the Incredible Hulk.

In 2006, a year and a half after Tim chuckled at JJâs naive suggestion that he would someday climb El Capitan with Jason, the men finally made plans to tackle Yosemiteâs most iconic wall. They settled on an ambitious goalâascendingÌęthe Nose in a dayâa feat many recreational climbers only dream of. JJ drove to Yosemite for the occasion with their one-year-old son, Levi, in tow. As they settled in to sleep the night before, JJ recalls Tim having first-time jitters, but also a quiet confidence that, with this partner, he would finally summit.

After 22 hours of grueling climbing, Jason and Tim topped out a few hours after Levi had taken his first steps on the El Cap bridge, a gathering place for Yosemiteâs big-wall climbers. Tim was elatedÌębut also apparently content to tick El Cap off his bucket list. âThank you so much, man. Iâm good. I just wanted to do it this one time,â he told Jason as they poked around for the hiking trail that would lead them back down El Cap to their families in the valley.

Jason, however, was like a confidence hypnotist. Spend enough time around him and suddenly, without realizing it, you were doing things you didnât believe yourself capable of. If he sensed someone was truly frightenedâlike the time the shale began to shift under his dadâs feet on a cliffside hike in the Sierraâhe would never push. But if he thought someone had more of themselves to give, it was a different story. His favorite refrain was âjust one more pitch,â says Becky, who often climbed with him. He would repeat it over and over until the summit.

Whether Tim came around by himself or Jason persuaded him to climb El Cap just one more time,Ìęthe pair was far from finished. They would go on to summit the hallowed formation at least 75 times together over the next 12 yearsâalways in less than a day. Legendary speed climber Hans Florine, who keeps an unofficial tally of El Cap climbs and holds the record for most ascents (165 as ofÌęOctober 2018), calls this volume âtotally amazing.â

âThey could probably be silent the whole day and still know each otherâs moves,â Florine said. âItâs like an old married coupleâyou put the saucer underneath the coffee cup before your partner puts it on the table.â By Florineâs count, Tim was one of four peopleâand the only recreational climberâto scale El Capitan more than 100 times (at least 106).

Familiarity with one another and the El Cap routes they climbed allowed Tim and Jason to move quickly. While it took more than 22 hours the first time they climbed the iconic wallÌętogether, they would later summitÌęin as little as five hours.

In mid-May, Jason and Tim found themselves blazing up the Nose right behind Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell, who were practicing to break the speed record. When he saw Jason and Tim approaching, Austin Siadak, a photographer documenting Caldwell and Honnoldâs effort, yelled up the wall to Honnold: âDude, you better get moving or youâre gonna get passed!â

Tim and Jason did not climb quickly to attract attention. Tim was âphysically unableâ to brag, explains Jim Herson, another one of Timâs frequent climbing partners. Jason was the same. Since 2015, he and his friend Stefan Griebel have held the speed record on the Naked Edge, a classic climb in Boulder. But when chatting with acquaintances about the route, he would simply say, âItâs a great climb!â

Tim and Jason knew they would never break a speed record on El Capitan. Nor was that something they aimed for. They climbed fast in Yosemite simply so they could climb more.

Many climbers call El Capitan the Big Stone; Jason referred to it as the Magic Stone.ÌęEven as it shredded their hands and strained their muscles, nothing restored the partners more than working their way up its cool granite face. Scrambling over the top, peeking down at the imposing valley below made them feel keenly full of life, but also at peace.

They chased that sensation relentlessly. â[After climbing Triple Direct we] found ourselves [at] the base of the Nose at 8 P.M.,â Tim wrote in a SuperTopo trip report in 2011 that chronicled a trip in which he and Jason aimed to climbÌętwo routes up El Cap in a day. âWe ended up passing parties camped on all ledges including a couple of parties in port-a-ledges. During the lower sections, Jason was somehow able to arrange the rope to make sure it kept smacking every sleeping individual in the head, setting me up for an explanation and profuse apologies.â They finished both routes in a little over 24 hours. On another trip, Tim and Jason climbed the Nose twice in one dayâthe only time in history a team has ever done so, according to Florine.

Both men seemed able to survive on less sleep than other people. On climbing days, Jason would pop out of bed around 4 A.M., mainline Peetâs coffee, and blast Metallica out of his portable speaker. Tim was comparably energetic. Once Herson commented in passing that he was turning 54 and wouldnât linking the 54 pitches of El Capitan and Half Dome be a fun way to celebrate. The next morning Tim texted: âI checked my calendar. I have an all day conference in Sacramento Saturday that ends at 7pm. I’ll drive to the Valley by 11pm.ÌęWeâll start climbing at 2am. Topout by midnight and run back to the car, start driving by 2am, and get to school by 7am. I might have to skip the shower before class though.âÌęHerson was tempted to take a nap just reading the text. But Tim meant it. Ìę

It is difficult to carve out time for hobbiesâeven those that electrify us. There are work obligations, budgets to balance, and family members in want of attention. It wasnât that Tim and Jason didnât think about such things. But suspended thousands of feet above the ground, they were forced to focus on the present: Can I stretch my foot to that nub of rock? Will my hand jam into that crack? Is that sliver of granite textured enough to grip?

It was their form of meditationâand they knew they would be kinder, happier, and more effective in every other facet of their lives if they leaned into the joy and serenity that climbing brought them.

Last summer, on June 2, the men woke before the sun and headed to the El Cap bridge to pick up another friend. While Tim and Jason usually climbed as a pair, this time they had invited Kevin Prince, a medical resident whom Tim had met in 2009 when he was part of the Yosemite Search and Rescue team.

The trio reached the base of El Cap just after first light. Their chosen route that day was the SalathĂ©, a 2,900-foot 35-pitch route which Tim and Jason had summited together,Ìęand once with Prince.ÌęThey racked up and began their ascent around 6:30 A.M.

They were climbing what Prince describes as caterpillar style, with Jason and Tim connected by one rope and Tim and Prince connected by a second rope. Jason would climb a pitch and tie the first rope to an anchor. Then Tim would jug up behind, stepping his feet into aid ladders and pushing ascenders up the rope until he reached the anchor. At that point, he would clip himself into the anchor, put Jason on belay for the next pitch, and fix the second rope so Prince could follow.

The three men moved quickly up the rock, whose grooves and cracks were by then as familiar to them as the turns of a commute. By the third pitch, Jason had caught up with Jordan Cannon and Jeremy Schoenborn, two young climbers who were attempting a free ascent of Golden Gate, a difficult route up El Capitan that begins with the first 20 pitches of the Salathé. They were climbing with ropes and protective gear, but no aid tools. After Jason had waited behind them at the second belay for 20 minutes, Cannon and Schoenborn offered him the chance to pass. Jason refused, stating excitedly that he wanted to see them tackle the next section: a roof he had successfully navigated dozens of times before. No one was in a rush.

As Schoenborn followed Cannon up the fifth pitch, a difficult section of slab where climbers must rely on friction and balance to advance up the wall, Jason climbed close behind him and the two got to chatting. Jason told Schoenborn how much fun he was having and how stoked he was to see two climbers in their early twenties gunning for a free ascent of El Cap. At one point, theÌęconversation turned to Alex Honnold and how crazy it was that he had navigated such hairy slab moves with no ropes during his 2017 freesolo of Freerider, which takes a largely identical route to the SalathĂ© wall with a few variations to avoid particularly gnarly sections.

Tim and Jason knew they would never break a speed record on El Capitan. Nor was that something they aimed for. They climbed fast in Yosemite simply so they could climb more.

At the top of the sixth pitch, at a spot known as Triangle Ledge, Jason, Tim, and Prince finally passed Cannon and Schoenborn. As Tim belayed Jason, it became obvious to Schoenborn that he was in the company of some of the best climbers he had ever encountered.

âJason sure is a superhero,â Schoenborn said as he watched him float up the nextÌępitch.

âHe really is,â Tim replied.

From Triangle Ledge, the trio scaled approximately 100 feet of moderate terrain before traversing into the Half Dollar, a trickier section nearly 1,000 feet off the ground where climbers must shimmy up a fissure in the wall. When Tim emerged at the top after Jason, he fixed Princeâs rope to an anchor and Prince followed up the Half Dollar, his view of his partners obscured by the granite chimney.

Meanwhile, Jason and Tim continued into the relatively easy terrain that leads to the top of Mammoth Terracesâthe on the route.ÌęIt was such a tame section Tim and Jason often climbed it at the same time.

Around 8:05 A.M., as Prince was still working his way up the Half Dollar, Schoenborn heardÌęâsomeÌęslamming noisesâ and saw Tim and Jason falling through the air less than 50 feet to his left. The rope connecting them likelyÌęcaught on something, briefly arresting their fall. Then it severed and the men continued downwards.

Prince poked his head out of the Half Dollar in time to see two men and a rope drop by him. âI hope they didnât hit Tim and Jason,â he remembers thinking as he raced to the anchor. Nearing the top of the chimney, where he would be able to see the next section, it dawned on him that it might have been Tim and Jason. But it didnât make sense, he thought, there was no way they would have fallenâparticularly in such easy terrain.

When he emerged from the Half Dollar and saw the wall above was empty, he dialed 911. Yosemite dispatchers picked up andÌęhe told them Jason and Tim were dead at the base.

Tim and Jasonâs deaths shocked the climbing community. Their accident sparked frenzied posting in climbing forums as people speculated about what happenedâdid the men not place enough gear, or not place it correctly?

Later, Yosemite rangers released aÌęreport on the accident. It did not determine who fell first or why. But it did suggest that something went wrong before Tim and Jason fell.

When Prince arrived at the top of the Half Dollar, he found that the rope connecting him to Tim had been untied and left fixed to a piece of protective gear wedged into the rock. This suggests Tim had to continue up the wall for some reasonâto shake loose a stuck rope, perhapsâbut intended to return, otherwise Prince would have been stranded (though totally secure, as he was tied in to an anchor).

The report also suggestedÌęthat Tim and Jason had placedÌęno protective gear in the section where they fell, adding that: âThe difficulty of the terrain in the section of rock leading to Mammoth Terraces is relatively moderate and would lend itself to experienced climbers placing less protection.ÌęHowever an unprotected fall in any terrain has catastrophic consequences.â

Jason and Tim were not adrenaline junkies and they certainly werenât in a rush. âWe were, essentially, on a casual trail run up our favorite mountain,â Prince recalls.

Both Becky and JJ chafe at the idea that their husbands were doing anything uncommon for climbers of their ability. Something just happened to go wrong, in the way that it can while driving on the freeway, or walking down the stairs. Perhaps a loose rock hit one of them, or a bird; both women find it hard to believe that either Tim or Jason simply slipped.

While on a hike in Coloradoâs El Dorado Canyon State Park in September, Becky, who was by then seven months pregnant, tried to explain. âLook, itâll be hard for a non-climber to understand but they were just really comfortable on the rock. That was like their home. It was like walking on a little sidewalk for them,â she said. âI mean could they have done something different? Iâm sure. But we could say that about a lot of things where something goes wrong.â

Since June, Tim and Jasonâs loved ones have paid tribute to the men in myriad ways. After Jim Hersonâs 15-year-old son, Connor, climbed the Nose without using any aid equipment in Novemberâbecoming by far the youngest of the only six people to do soâhe clipped one of Timâs locking carabiners to a bolt near the summit in celebration. âNo two climbers have ever had [as] much fun on El Cap as Tim and Jason and they shared it with all of us,â Jim narrated in a summit video. âSo when you top out on the Nose and you see Timâs biner here: think of Tim and Jason and all the fun they had.â

Others have organized memorial services or taken long hikes in wild places. They have prayed. They have gotten tattoos in the shape of mountains. They have delivered vats of fried rice and coolers full of wraps to Becky and JJ to make sure they eat despite their sorrow. They have placed memorial plaques atop steep trails where those who want to pay their respects will need to sweat to do so.

But above all, they have endeavored to live by Tim and Jasonâs example.

When I traveled to Boulder to interview Becky, despite her searing grief and constant morning sickness, she offered to take me climbing. As we drove up the sinuous road that leads to Boulder Canyon, where one of Beckyâs friends was celebrating his birthday by climbing laps with his wife, my palms began to sweat. I was happy just to watch, I told Becky, hoping she wouldnât notice that my voice had raised an octave.

She turned to me, her blue eyes twinkling, âJust try one pitch.â