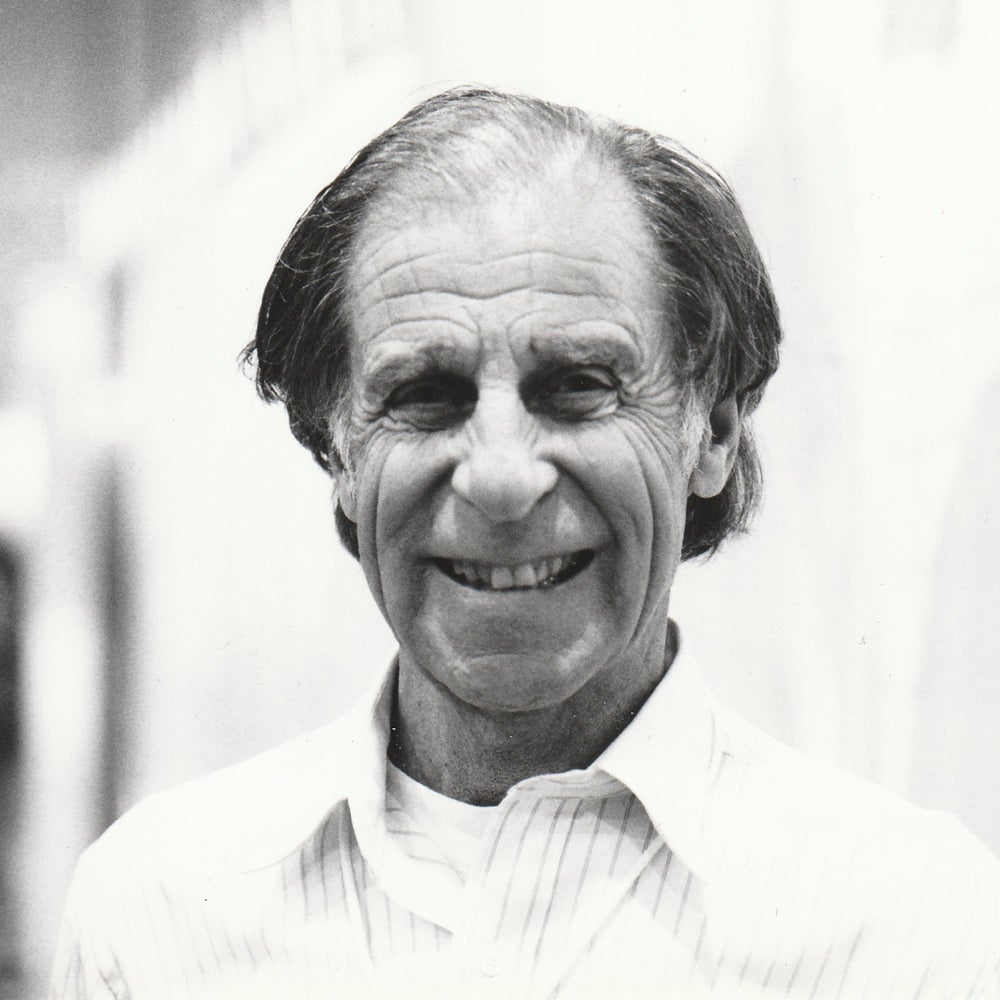

Fred Beckey, widely hailed as North America’s most prolific climber and mountaineer, died Monday in the Seattle home of his friend and partner, Megan Bond. He was 94.

“We were planning another trip to the Himalaya for next spring. He had a lot more to do,” says Bond. “He had a good death and a great life.”

Reactions to his death, both among those who knew him and among the broader climbing community were swift and all of apiece:

Legendary.

“They'll never be another Fred Becky,” wrote climber and writer John Long on . “No words.”

When contacted in Seattle this evening, Bond, who is writing a biography of Beckey, said, “Our deep friendship spanned six countries, ten western states, hundreds of bivouacs, and travel over many tens of thousands of shared vertical feet and lateral miles. We spent over a decade together climbing, exploring mountains, wilderness terrains, remote regions, and engaged in shared intellectual and literary pursuits.”

Born in Dusseldorf, Germany, in 1923, Beckey was two years old when his parents, Kalus (a physician) and Marta Maria (an opera singer) emigrated to Seattle with him. Within 14 years, Beckey had become the enfant terrible of Cascades climbing. Described by climbing historian Andy Selters as “a one-man tornado,” Beckey, “a 16-year-old with almost disturbingly fearsome intensity,” climbed 35 peaks in his first year as a member of the , a Seattle-based climbing club. Within another three years the 19-year-old, climbing in tandem with his younger brother Helmy, made the second ascent of British Columbia’s , with Fred ingeniously using felt slippers over his tennis shoes to surmount a crux ice chimney. Waddington’s reputation at the time was fearsome. In a reminiscence of Beckey on Supertopo, climbing historian Chris Jones called Waddington a “forbidding, remote peak that had turned back the best climbers of the day. How many of us were even born, let alone climbing then! And he was just warming up.”

He had a passion for seeking the unknown that is probably unparalleled.

Warming up, indeed. It was Beckey’s keen intellect combined with an insatiable appetite for ascent that propelled him up some of the country’s most remote—and obvious—rock walls and mountain faces. The Beckey name, it seems, is strewn in the indices of every important guidebook in North America, including Steck and Roper’s , and Jones’s . In 1954 alone, he climbed both the south ridge of 12,540-foot Mount Deborah and the west ridge of 14,573-foot Mount Hunter, in Alaska, both with Henry Meybohm and Heinrich Harrer, the latter of Eiger fame. He also made the first ascent of the Northwest Buttress of Denali that year.

“He had a passion for seeking the unknown that is probably unparalleled,” said past president of the , Jim McCarthy, speaking from Colorado. “The real thing about Fred is that he is a monument to future generations.”

Beckey, it seemed, left none of the continent’s ranges untouched, either by hand or in print. After receiving an undergraduate degree in business administration from the University of Washington, Beckey cobbled together a life that had him climbing and writing about climbing. With a near-encyclopedic knowledge of the Northwest’s mountain geography, Beckey either authored or co-authored at least eight guidebook-cum-histories, including the three-volume , the definitive source for climbs in that range.

A past honorary member of the American Alpine Club, Beckey was also awarded, in 2015, the President’s Gold Medal—an award given to only four other climbers in the Club’s 115-year history. In 2013, Beckey won the Adidas Lifetime Achievement Award for his climbing accomplishments. Beckey, who has often been called the country’s ur-dirtbag—a climber who eschews riches to pursue climbing full-time—was made the subject of an of that name.

“He devoted his life to advancing climbing and he succeeded,” says McCarthy. “He deserves to be venerated.”