The Climber Comes Down to Earth

His life’s grand pursuit has killed his closest companions. His bride-to-be is his best friend’s widow. His exploding fame owes as much to happenstance (stumbling upon Mallory’s body on Everest) and luck (escaping an avalanche in Tibet) as it does to his great skill as a mountaineer. An intimate look at the serendipitous, tumultuous, and nearly unbearable success of Conrad Anker.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

You’re about to read one of the ���ϳԹ��� Classics, a series highlighting the best stories we’ve ever published, along with author interviews, where-are-they-now updates, and other exclusive bonus materials. Get access to all of the ���ϳԹ��� Classics when you sign up for ���ϳԹ���+.

Drinking his third latte of the morning on our way to ski Alta, Conrad Anker looked, for a moment, content. I’d pulled him away from his glad-handing duties at the Outdoor Retailer trade show, and as we drove through Salt Lake City’s suburban sprawl and into the frozen Wasatch Mountains, he seemed giddy at the prospect of some fresh air. Dark clouds hung low over the peaks, the snow-dusted road curved below shattered ribs of rock, and Anker, who lived nearby for a decade and a half, ripped apart a cinnamon bun and bubbled with nostalgia. Reaching across the dash, he pointed out an eagle’s nest, then a mixed ice-and-rock route he’d once done in a single day, then a snow chute he used to ski in late spring—“Big GS-style turns,” he recalled fondly, “not tips and tails.”

‘Torn’ Is a Wrenching Look at the Long Shadow of Alex Lowe

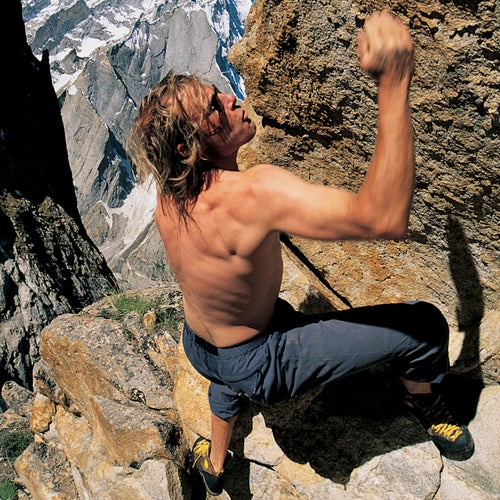

In a new documentary, the late climbing legend’s son, Max Lowe, explores his father’s high profile death, Conrad Anker joining the Lowe family, and the family drama that ensuedA handsome, 38-year-old alpinist, with boyishly side-parted blond hair, close-set blue eyes, and a lantern jaw, Anker looks more like a high-strung surfer than a consummate mountaineer. With no hiker’s thighs or gym-pumped muscles, there’s a surprising lightness to his physique, and his head leans perpetually forward, as if straining into the future. A sometimes wry self-promoter who talks earnestly about saving the world, Anker also has the playful manner of the outdoors Peter Pan. Which makes sense, given that he has spent his entire adult life in a very particular America—an adventure-sports subculture in which status derives less from money than from talent at skiing, kayaking, and climbing, a subculture in which well-meaning environmentalist and anticonsumerist opinions make up an informal state ideology. Success begins with finding work flexible enough to let you play whenever the powder’s deep, the ice is in, or the rock is dry. Greater success means making a living at some approximation of your game, like working ski patrol. True arrival means making a living doing the thing itself: travel, adventure, freedom.

Anker has been getting paid to play for most of a decade as a salaried, globe-trotting member of The North Face Climbing Team, and it’s been a great ride. But lately he has been negotiating the transition from being the favorite partner of some of the world’s great expedition leaders to becoming a leader himself. At the same time, he has had a painful reckoning with the costs of playing one of the world’s most dangerous games—costs that include his own brushes with mortality, the untimely deaths of his three closest friends in the high mountains, and the strange fallout that those deaths have had in his life.

Turning down the car radio, Anker gestured at a band of granite called Hellgate Cliff. He told me that together with his first serious climbing mentor, the legendary Mugs Stump, he established a notoriously committed rock climb there, Fossils from Hell, in the 1980s. (Stump disappeared into a crevasse in 1992 while guiding clients on Alaska’s Mount McKinley.) As we approached Alta, Anker remembered how he and another college climbing buddy, the underground hero Seth Shaw, had sometimes crammed an ice climb, a rock climb, and a few ski runs into a single day, even begged used lift tickets off skiers leaving Alta early. (Shaw was killed in May 2000 by falling ice, also in Alaska.)

“Wow!” he exclaimed as we rounded a snowbanked curve and a frozen waterfall swung into view. “Look at all the people on that ice climb! Wear your helmets today, boys!” Anker told me with evident pleasure that he and Shaw had held the round-trip speed record on that climb until Alex—Alex Lowe, Anker’s best friend and a man once considered the best climber in the world—shattered it. In the fall of 1999, an avalanche struck Anker, Lowe, and a friend named Dave Bridges on the flanks of Tibet’s 26,291-foot Shishapangma. Anker ran one way and survived, but Bridges, 29, and Lowe, 40, headed another way and disappeared. Lowe left behind a widow, Jennifer, and three young sons.

Even Anker’s most famous achievement is shadowed by ambiguities. In 1999 he joined the Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition to Mount Everest. That May, just above 27,000 feet, he found the 75-year-old remains of the British climber George Mallory. The discovery shed new light on one of the great unsolved mysteries of world exploration—what befell Mallory and his partner, Sandy Irvine, during the third summit attempt on Everest. But for Anker, who has put up important first ascents from Antarctica to Baffin Island, and who has no particular preoccupation with history, it was more a quirk of fate than the kind of cutting-edge climbing achievement of which he is most proud. Nevertheless, he was lionized in newspapers and magazines the world over; he coauthored (with David Roberts) a book on the Mallory expedition; and he has been on a near-constant speaking tour ever since.

By far the greatest change in Anker’s life came shortly after the October 1999 memorial service for Alex Lowe, in Bozeman, Montana. In what must have been a bewildering and exhausting half-year, Anker had come straight back from Everest to spend five months cowriting the Mallory book, flown off to Shishapangma with Lowe, survived a battering in the lethal avalanche, and returned just in time to go on a book tour. Everywhere he went, according to Topher Gaylord, longtime director of The North Face Climbing Team, “people were giving Conrad so much support. But he had to go back alone to his hotel room every night, and it didn’t bring Alex back, it didn’t change anything. I think that’s where Jenny and the kids became the best way of coping with losing Alex.”

In a series of events that Anker understandably preferred not to discuss with a journalist, he eventually broke off his wedding engagement to an environmental lawyer named Becky Hall and became romantically involved with Jennifer Lowe. In December he proposed, and they plan to be married by the time this magazine arrives on the newsstands. Anker now lives with Jennifer and her sons in the Lowe home in Bozeman—finding himself, in other words, husband-to-be to his best friend’s widow and stepfather to three boys who lost their father while he was climbing beside Anker himself.

In Little Cottonwood Canyon that day, Anker did not dwell on his own and his new family’s losses, and this was only partly because he knew that I already knew all the details. He also resolutely insists on a life-affirming view of his profession. In his Mallory slide show—the story of yet another young husband and father who died climbing—Anker doesn’t mention the half-dozen mangled corpses that he came upon on Everest and that he describes in his book. He never shows the macabre photographs of himself looming over Mallory’s grisly body. (He criticized this magazine for running one of these shots on its cover.) He sometimes even tells audiences, in all sincerity, things like, “If I can motivate just one of you to go home and plan just one climb tonight, I will have done my job.”

Anker is, of course, a paid spokesman for The North Face and a man who has never known much beyond extreme alpinism. But one senses, too, that he feels a great compulsion, even obligation, to argue aloud that his chosen profession has been worthwhile and that Alex Lowe did not die foolishly—that his life’s foremost pursuit is still as it has always seemed: good for body, soul, and mind, and inspired by grand purpose.