When top British alpinists Kevin Thaw, 35, and Leo Houlding, 23, launch their climb on the 5,000-foot north face of Patagonia’s Cerro Torre, in late February, they’ll be understandably skittish. Hurricane-force winds can descend on the exposed route with little warning, and on their last attempt, in 2001, Houlding fell 70 feet on the ninth pitch, shattering his right foot. After they rappelled down, Houlding crawled across a section of ice and rock, then Thaw carried him six miles to base camp.

Dispatch: Climbing Patagonia's Cerro Torre

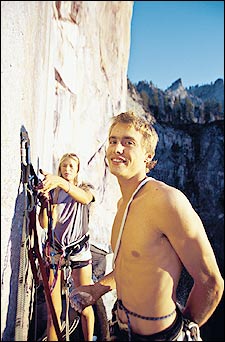

Like a rock: Houlding in Yosemite with climing partner Jessica Corrie

Like a rock: Houlding in Yosemite with climing partner Jessica Corrie

“It’s a massive face with very temperamental ice and snow,” says Houlding. “Add violent weather and it’s an incredibly dangerous route.”

So why try again? Because if they summit, they’ll grab one of big-wall climbing’s greatest prizes—and possibly end a legendary controversy. The two plan to retrace an unrepeated first ascent claimed 45 years ago, by renowned Italian mountaineer Cesare Maestri and his Austrian partner, Toni Egger—and debated for nearly as long.

According to Maestri’s account, on the evening of February 1, 1959, a day after completing what was considered an impossible line up the north face, he and Egger descended to 1,000 feet above the Torre Glacier. As Maestri lowered Egger down the wall in search of a ledge on which they could spend their sixth and final night out, an avalanche struck, sweeping Egger to his death.

Though the team’s only camera disappeared with Egger, the mountaineering community accepted Maestri’s word that they had summited, and he became a hero. He went on to write six books on his adventures. But in 1970, a rival Italian mountaineer sparked doubts about the Cerro Torre ascent when he suggested in a magazine article that the peak was still unclimbed. Others joined the attack, fueled in part by Maestri’s foggy recollections of the north face’s final pitches. In response, Maestri in 1971 climbed Cerro Torre by the easier southeast ridge—now the peak’s standard route. But that did nothing to stop questions about the 1959 expedition.

These days Maestri, now 74, says he’s grown tired of defending himself. “Not in my entire life have I doubted the ascent of a mountaineer,” he says. “It hurts.”

The controversy, however, remains alive. “Whether Maestri and Egger made it or not is one of the great mysteries in alpinism,” says Mark Richey, 45, president of the American Alpine Club.

The key to solving it may lie on the north face’s upper headwall, where Maestri says he placed a series of bolts. If Thaw and Houlding find them—no sure bet, given that they’d have to pass precisely over the ’59 route—then Maestri’s story will gain new credence.

Whatever happens, the climb will be one of the year’s most ambitious. The men plan to blitz the face in a two-day sprint—all the while keeping a wary eye on the weather. “Given the right conditions, we’ve got a great chance,” says Thaw, “but if a storm hits, we could be doing some serious kite impressions.”